How Russia employs fake fact-checking in its disinformation arsenal

Kremlin-aligned outlets embrace open-source research and fact-checking tropes to make disinformation more convincing.

How Russia employs fake fact-checking in its disinformation arsenal

Share this story

BANNER: Logo of Russia’s Channel One program “AntiFake,” which presents propaganda and disinformation as fact-checking. (Source: 1tv.ru)

The Kremlin and Kremlin-aligned media are co-opting fact-checking tropes to spread disinformation and distort the truth about its invasion of Ukraine, undermining the trustworthiness of fact-checking as an institution.

The Kremlin has long been a fan of stoking conspiracy theories about its enemies, but these have often come directly from the mouths of government officials and Kremlin-adjacent media pundits who could easily be viewed as biased. Now, the tactic of fake fact-checking leverages the way people process information to make conspiracies more believable.

Just as Russia has mirrored Western claims of being the target of information warfare, they have pilfered Western fact-checking and open-source research tropes to pollute the information space regarding the war in Ukraine. In practice, fake fact-checking works like this:

- Russian citizens are primed to question news coming from Western-friendly sources due to years of being told that Russia is a target of Western information warfare.

- Fake fact-checking organizations are created, framing themselves as apolitical or driven by independent experts, and begin releasing “analytical” content that borrows tropes from legitimate fact-checking organizations and open-source researchers. A large portion of their “fact-checks” are fake or inaccurate.

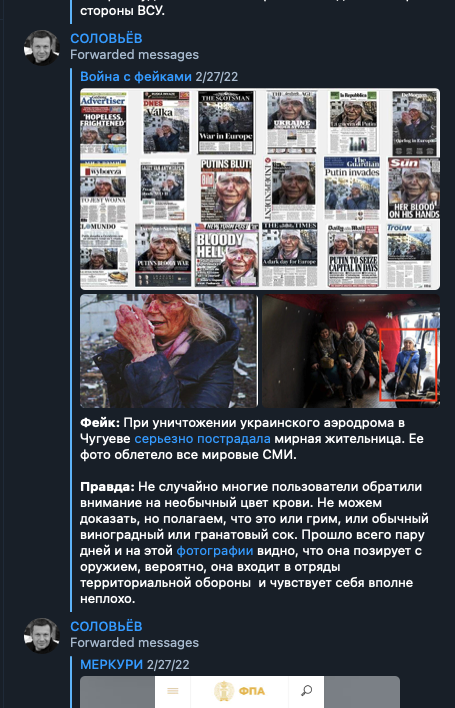

- Fake fact-checks are amplified by Russian media pundits, Russian state television, or the Russian government itself to reach a wider audience and create more legitimacy through endorsement.

- When sharing information from supposedly apolitical sources, the Kremlin and Kremlin-adjacent sources distance themselves from the fact-checks, allowing the information shared within them to carry the moral authority often associated with objective fact-checking institutions. Disinformation now appears more credible and less obviously influenced by the Russian government.

- Fake fact-checks are shared widely — mostly within the Russian-speaking community, but also in other languages — as an “objective” source of information about the war in Ukraine.

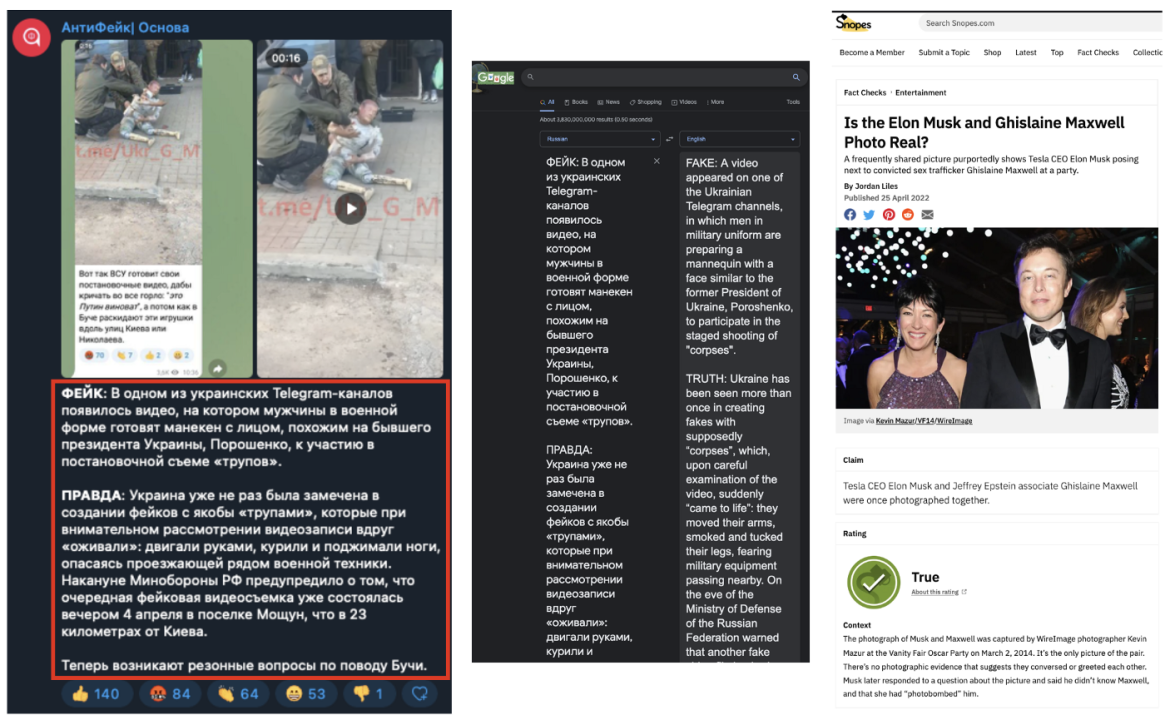

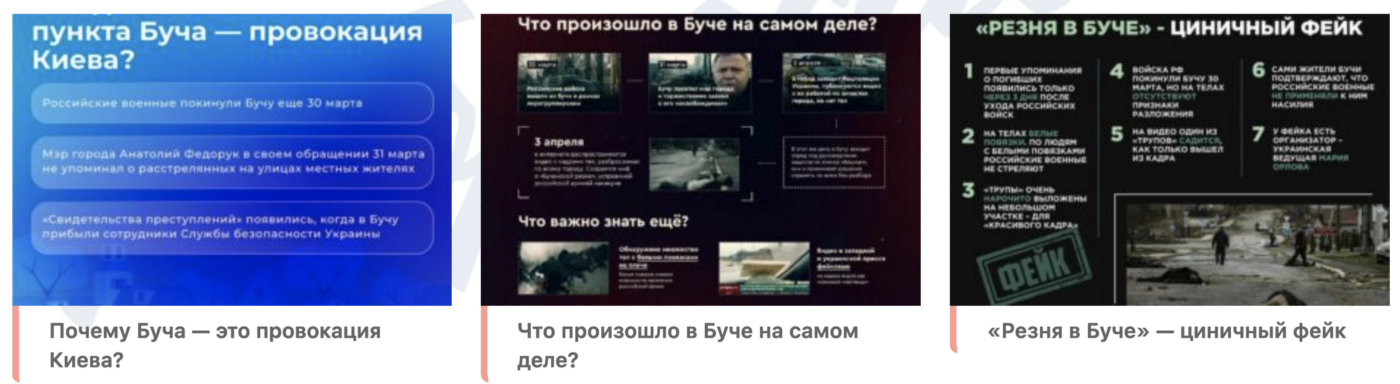

The DFRLab has watched this tactic grow in real-time, as Russia has identified its effectiveness in suppressing information on topics ranging from anti-war protests to war crimes. It involves a combination of different types of fact-checks: (1) true or partially true fact-checks; (2) fake fact-checks of real news; and (3) debunks of “Ukrainian disinformation” that was never actually spread by Ukraine — essentially, a forgery presented as strategic disinformation.

Collectively, Russia’s use of fake fact-checking is reaching millions of Russian citizens and expanding to other parts of the world, especially the English-speaking community. Its success poses a significant threat to the Ukrainian cause, as well as the legitimacy of fact-checking as an institution.

Since the start of the Russian invasion, the DFRLab has identified an overlapping web of outlets employing fake fact-checking — it includes Telegram channels, websites, Vkontakte (VK) accounts, and Russian government social media accounts, including those of state media and state television. All these outlets either have direct connections to, or have been heavily amplified by, the Kremlin. Although we cannot yet prove that all are part of a larger information manipulation strategy, the rapid growth of this tactic, the resources allocated to these outlets, and the striking similarities between them indicate all the hallmarks of Russian government involvement.

What makes fake fact-checking so dangerous?

Russia’s employment of fake fact-checking tropes following its invasion of Ukraine is not entirely new; they have tested out smaller-scale attempts in 2017, and the tactic is a variation on Russia’s efforts to discredit its enemies through lies or half-truths. War on Fakes, a fake fact-checking outlet, even hinted at this similarity when it compared a video of a wounded child in Mariupol to “staged” videos created by the White Helmets in Syria.

The key difference with fake fact-checking is that it plays into cognitive biases and how society has been primed to process information in the digital world. Masquerading as apolitical fact-checking organizations allows these outlets to project — despite its actual absence — the moral authority society places on fact-checkers, playing into what’s known as authority bias. Authority bias, as documented in the research of psychologist Stanley Milgram, is the tendency of people to trust and respect authority figures because of their authority. In this scenario, individuals may be more likely to trust information from a supposed fact-checking organization — which carries with it the notion of being an authoritative source — than from an unnamed group of people who post claims about Ukrainian disinformation.

In conjunction with authority bias, people tend to feel that information that may be biased is less credible. Even Russian citizens who have some conception of Russian media bias may believe the content they are sharing if it comes directly from a supposed fact-checking organization, as it would typically imply a more objective and analytical approach.

Fake fact-checking also leverages our psychological preference for information that appears to be effortful and professional. Borrowing methods from the open-source community, which appear detailed and highly analytical, these outlets pass off their content as more legitimate and trustworthy than it actually is. Fake fact-checkers also often employ visuals that are engaging to readers and can be remembered more easily than text, making it more likely that they will be shared either via social media or word of mouth.

War on Fakes and related channels

The Telegram channel War on Fakes, which claims to be an apolitical fact-checking organization, was one of the early adopters of this tactic, first appearing on February 23, 2022. With over 700,000 subscribers at the time of writing, War on Fakes has propelled itself into becoming one of Russia’s top Telegram channels. The organization runs at least eight Telegram channels: the original, an analytic channel, Kalmykia, Crimea and Sevastopol, Belgorod, Rostov, Voronezh, and Kirov. They also host websites in Russian, English, French, Spanish, Chinese, and Arabic. The DFRLab has previously reported on War on Fakes.

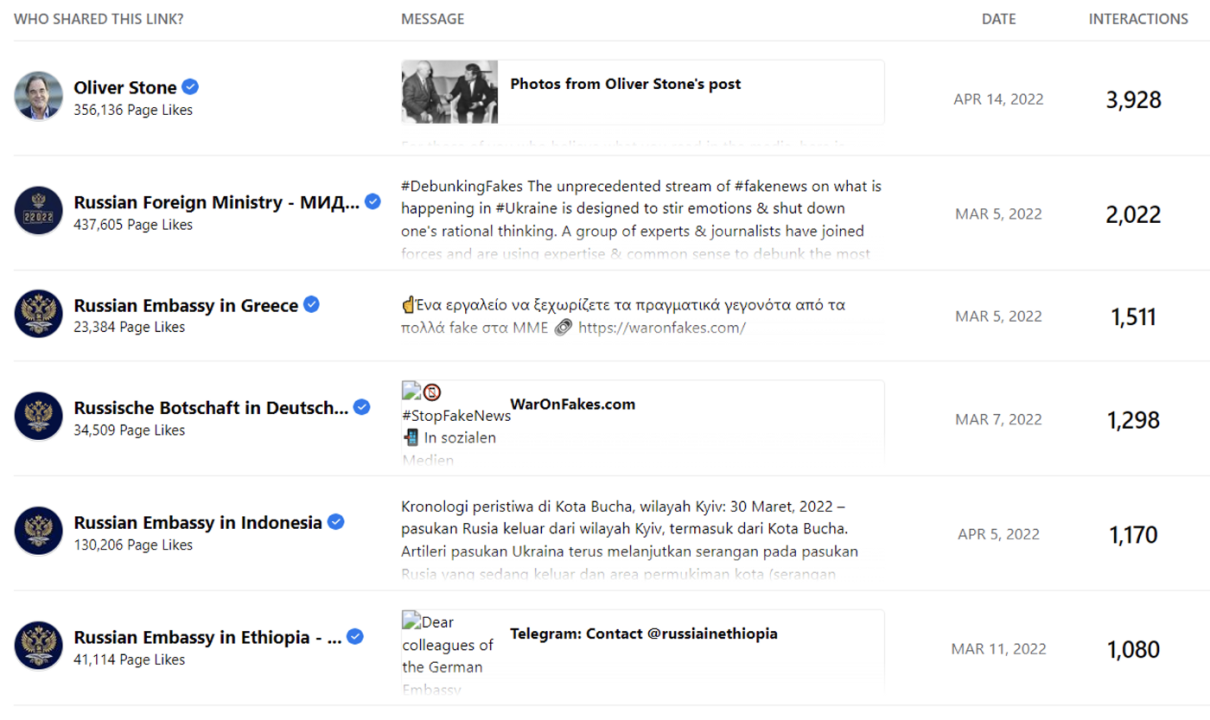

As noted in previous DFRLab reporting on the channel, Russian embassies and other government-affiliated accounts have heavily promoted War on Fakes’ English-language website on Facebook and Twitter, and its flagship Telegram channel has been amplified on VK via what seems to be state-coordinated sharing. Two of War on Fakes’ articles were recently shared on Twitter by US film director Oliver Stone, suggesting the groups’ content is slowly breaking into Western circles. According to a DFRLab query using the Meta-owned social media monitoring tool CrowdTangle, Stone has also shared links to War on Fakes to his official Facebook page.

War on Fakes has also promoted other Telegram channels, though it remains unknown if the same operators are behind these channels as well. One of these channels, Zа Правду/For The Truth, describes itself in Russian as an “informational Telegram channel created to disprove fakes and bring the truth to the West in their language” and in English as an “Anti-Fake news Telegram channel.” It regularly re-shares War on Fakes posts and has supposedly worked with War on Fakes to do English translations of their content, especially around the Bucha massacre.

Another related Telegram channel is Mrakoborets (“Мракоборец,” or “dark fighter” in Macedonian). Mrakoborets is a reference to the word used in Russian translations of the Harry Potter books to refer to wizards employed to fight dark magic. The channel appears to mostly crowdsource harassment and complaints against other Telegram channels it claims are posting fakes, which generally equates to any channel sharing content that does not align with the Kremlin’s preferred messaging around the war. War on Fakes promotes Mrakoborets as a helpful channel for “blocking the distributors of fakes and writing complaints against them.” Although this channel is not explicitly engaging in fake fact-checking, it ties into the greater narrative of a Western information war against Russia and serves as another way to push Russians to close off their information environment further. Though not a definitive indicator of coordination, this channel uses similar font, styling, and coloring to War on Fakes in the images it designs.

Other Telegram channels

Numerous pro-Russian Telegram channels now exist that were all created after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine with the stated purpose of disputing Western fakes, particularly those about Russia’s “special operation” in Ukraine. A few examples of channels with significant reach are Fake Cemetery, Antifake Osnova, and Antifake Z. It is unclear who runs these channels, but they use similar methods to War on Fakes, contrasting a “Fake” to the “Truth” by borrowing tropes from open-source researchers, such as highlighting points of interest on satellite imagery and stamping a large, red “Fake” symbol over images. Fake Cemetery and Antifake Z have both re-shared multiple posts from War on Fakes.

Defending the “truth”

Outside of War on Fakes’ various language sites, one other site stands out as a key spreader of fake fact-checks: Zanami Pravda, or ‘Defending the Truth.” Previously reported on by Sky News, Zanami Pravda hosts an “Antifake” page where users can upload content purported to be Western fake news about the war. Users who post the “best patriotic content” can win prizes like music and television subscription services. The organization has over 200,000 followers on VK and more than 110,000 subscribers on Telegram.

Zanami Pravda is coordinated by the All-Russia People’s Front, of which Vladimir Putin is the head, tying its “anti-fake” content directly to the Russian government. The amplification of the site looks similar to that of War on Fakes: copy-and-pasted text shared on VK by government-funded entities, such as schools, libraries, and local government or news pages. It has also been advertised heavily by Russian media. Zanami Pravda’s Telegram channel frequently shares content from War on Fakes.

While its Telegram channel remains active, at the time of publishing, the Zanami Pravda website was no longer accessible. An archive can be found here.

Russian state television and media

Russian state TV and media quickly took to fake fact-checking after the outset of the invasion of Ukraine; many channels and outlets now amplify content from groups like War on Fakes or create their own highly sensationalized content.

Researchers have identified countless examples of Russian state TV channels using fake fact-checking, including Russia’s popular Channel One. Some have even created their own TV shows and segments that cover supposed Ukrainian and Western fakes. One particularly sensational new show is AntiFake, hosted by Channel One. Each week, AntiFake host and former home-video clip show presenter Alexander Smol brings on alleged experts to discuss fakes about the war in Ukraine. Many of these narratives are the same as those shared across other fake fact-checking outlets mentioned in this piece. As is consistent throughout these outlets, AntiFake purports to take an analytical approach and deploys common fact-checking tropes to bolster its apparent legitimacy.

The DFRLab has identified other instances of Russian outlets creating their own fake fact-checking segments, including “Stop Fake” by RT and “War on Fakes” by RU Baltic. The RU Baltic segment does not appear to be related to the original War on Fakes organization but does share similar content.

Russian print media also plays a significant role in promoting the narrative of an information war against Russia and providing fake fact-checks to support this. The DFRLab has found extensive amplification of fake fact-checking by popular Russian media outlets like RT and Lenta, as well as hundreds of Russian articles amplifying fake fact-checks.

Russian government entities

The Kremlin has shown its own proclivity toward fake fact-checking through its recent usage of fact-checking tropes and amplification of content from the outlets mentioned in this piece. For example, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs now posts “Your Daily #Fake,” which includes a short video debunking supposed disinformation. These are then often distributed by Russian diplomatic Twitter accounts. The Russian Embassy in the United Kingdom, for example, received heavy criticism for sharing a fake fact-check that was removed by Twitter. Russian government fake fact-checks are often sensational and clearly designed to engage viewers with hashtags, emojis, and video/imagery.

The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Defense have both shared War on Fakes posts on Twitter and Telegram; the latter, in particular, has re-shared the fake fact-checking Telegram channel’s content dozens of times. Additionally, Russian Embassy accounts on Facebook and Twitter have shared the channel’s contents hundreds of times.

Russia’s use of fake fact-checking poses a three-fold threat by (1) heavily distorting Russian citizens’ perceptions of the war in Ukraine and the West; (2) moderately distorting global perceptions of the war; and (3) sowing public distrust in legitimate fact-checking institutions by polluting the information environment more generally. As Russia continues to cut off its citizens from what it deems to be “unfriendly” information sources, fake fact-checking bolsters false claims made by the Kremlin about the war in Ukraine. As this tactic appears more often in other languages, we may see fake fact-checks amplified by groups distrustful of Western institutions or mainstream media. This spread could result in longer-term impacts on public trust in fact-checking institutions, as individuals struggle to identify which organizations are truly objective and which fact-checks can be trusted.

Cite this case study:

Ingrid Dickinson, “How Russia employs fake fact-checking in its disinformation arsenal,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), May 4, 2022, https://dfrlab.org/2022/05/04/how-russia-employs-fake-fact-checking-in-its-disinformation-arsenal.