Busting Fakes, Kremlin Style (Part 2)

Fact checking RT’s “FakeCheck” project

Busting Fakes, Kremlin Style (Part 2)

Share this story

BANNER: Source: RT’s “FakeCheck”.

In this, the second of two reports on the Kremlin’s recent entry into the fake-busting world, the @DFRLab fact checks the “FakeCheck” project launched by Kremlin broadcaster RT. Read Part 1 here.

On March 15, 2017, Kremlin broadcaster RT announced that it was launching an interactive project called FakeCheck to separate “news facts from fakes.”

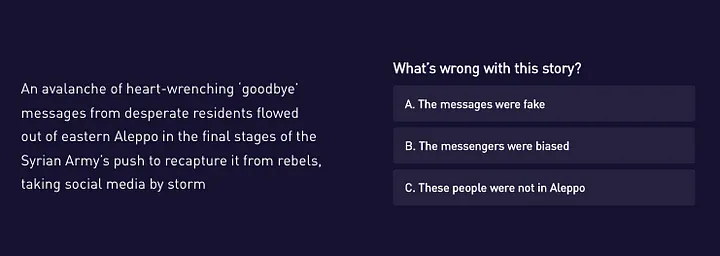

“FakeCheck” consists of an interactive portal in which the viewer is invited to click on a story, then answer a multiple-choice question on what is “wrong” with it.

The answer leads to a graphics-heavy, text-light explanation in a series of clickable pages. As of March 24, the project had nine entries.

RT’s initial announcement said that the page is “aimed at weeding out and correcting inaccuracies, bias, misinformation, and outright falsehoods in global coverage of major news stories.”

This statement is noteworthy for its sweeping nature, which goes far beyond exposing deliberately false stories (the working definition of “fake news” which will be used in this article — see DFRLab’s post, Busting fakes, Kremlin style (part 1)). It appears to be an attempt to police every aspect of news, including bias.

This is ironic, given that RT has repeatedly been found guilty by the UK’s regulator of violating the obligation to preserve “due impartiality” in its reporting.

The DFRLab has fact checked RT’s claims on all nine articles, to see whether they can legitimately be termed “inaccuracies, bias, misinformation and outright falsehoods.”

RT: Recycled Tweets?

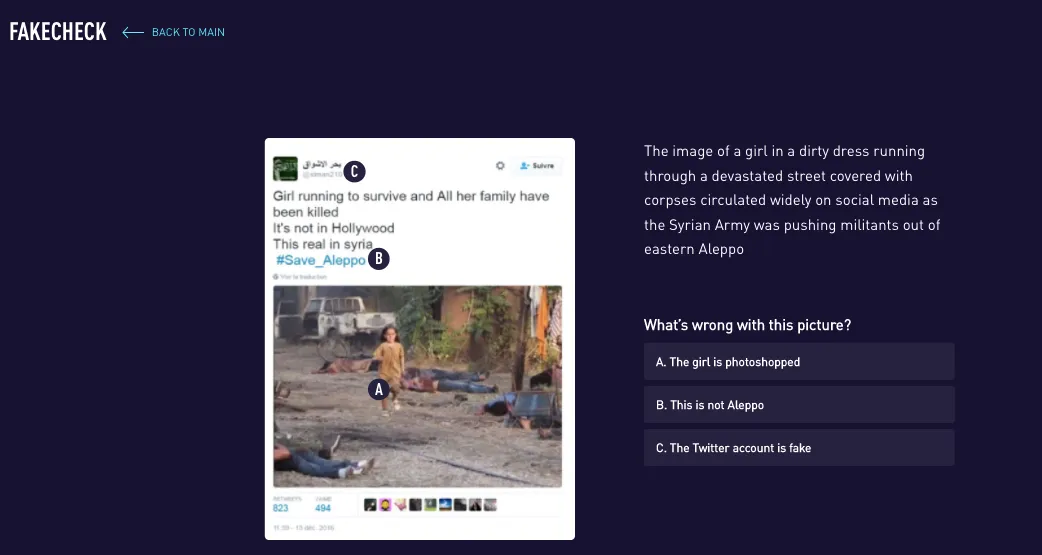

Some of the entries do concern actual fakes. The very first, for example, covered an image of a girl running through a battlefield which was tweeted on December 13, and purported to be taken in Aleppo.

In fact, the picture came from a Lebanese music video, and was exposed as a fake the same day — not by RT, but by Lebanese writer Sarah Abdallah.

Source: Sarah Abdallah / Twitter. Archived on March 22, 2017.

RT’s FakeCheck did not credit her with the finding.

The second entry concerned a report from US outlet Fox2 Detroit on January 31 that a woman in Iraq had died because she had been barred from the US by President Donald Trump’s entry ban.

Detroit family caught in Iraq travel ban, mom dies waiting to come home, reports @langeamyFOX2 https://t.co/zKFkkXZqO5 pic.twitter.com/aqApwsVKwZ

— FOX 2 Detroit (@FOX2News) February 1, 2017

Source: Fox2 Detroit. The time shown on the tweet is UTC; it was posted in the evening of January 31, Detroit time. Archived on March 22, 2017.

The story was based on a lie told by the woman’s son, and Fox2 Detroit confirmed it was a lie less than 24 hours later.

A third entry concerned a February 3 tweet, now deleted, purporting to be from the International Space Station, trolling US President Donald Trump. According to the New York Post, itself an outlet of questionable accuracy, NASA confirmed it was a fake the same day.

All these stories therefore do concern fakes; to that extent, RT’s inclusion of them in the FakeCheck project is uncontroversial.

However, their inclusion hardly constitutes a significant contribution to the global effort of “weeding out and correcting inaccuracies.” All three fakes were exposed within hours, and not by RT; all three occurred at least six weeks before FakeCheck was launched (and over three months in the case of the Syrian tweet).

This is, in fact, recycled content from a variety of sources.

A fourth entry covered a now-notorious article in the Washington Post, published on December 31, 2016, which claimed that Russian hackers had broken into the US electrical grid via a Vermont utility.

The article was substantially wrong, overstating both the scale of the problem and the nature of the hack. The Post was forced to correct and scale back its claims repeatedly, and was criticized both for its initial mistake and for the amount of time it took to correct it.

This is a clear case of inaccurate reporting; again, however, the original had been corrected by January 2, and the Post ran a parallel story the same day headlining that Russian hackers did “not appear to have targeted” the utility.

Once more, therefore, RT’s FakeCheck neither weeded out nor corrected the error, almost three months later; it simply recycled it.

Taking on the tabloid

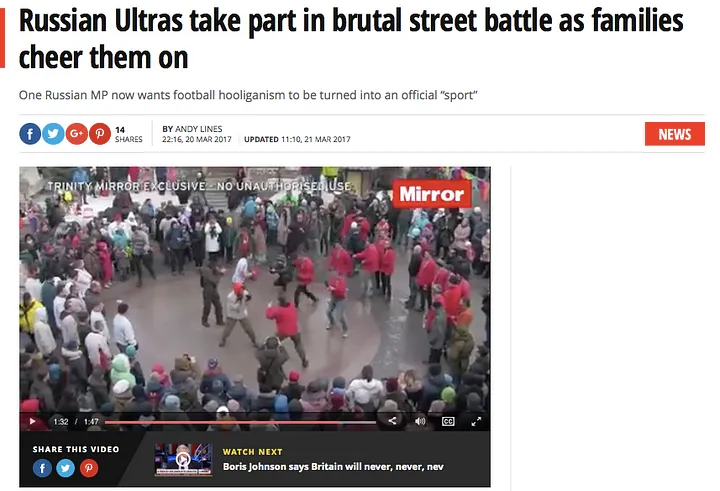

The latest offering in the series, published on March 22, was more timely, and concerned articles not apparently already debunked by the mainstream media. This was a pair of reports in English tabloid the Daily Mirror focused on Russian soccer hooliganism.

The Mirror’s reporting included an article and video on a “brutal street battle” involving “Russian Ultras”, a nickname for soccer hooligans. It is the latest in a string of reports from British media (for example Sky and the BBC) expressing concern over the possibility of soccer violence when Russia hosts the World Cup in 2018, after violent clashes between Russian and English fans in France in 2016.

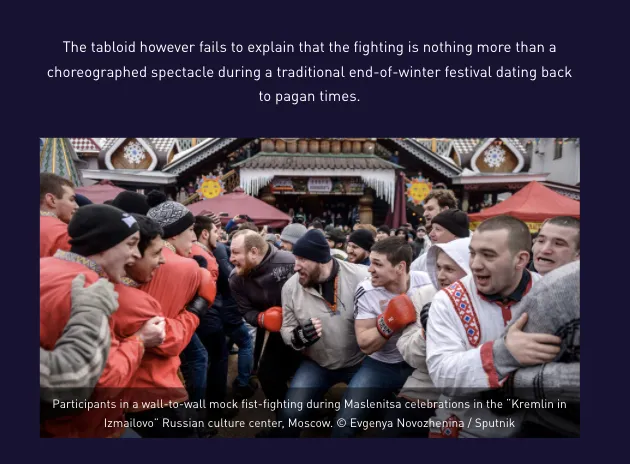

RT pointed out that the “street fights” were a well-reported Russian tradition, part of the “Maslenitsa” celebrations, the Orthodox equivalent of Carnival.

It is also worth pointing out that the fighters in the Mirror’s video were wearing traditional embroidered Russian shirts — unlikely attire for soccer thugs. Indeed, the Mirror’s article gave no indication of why it was identifying the fighters as “Russian Ultras”.

To this extent, RT’s exposure of the report appears entirely legitimate.

However, it also contained one anomaly. The rebuttal page focused on two Mirror articles — the feature on the Maslenitsa brawl, and a separate, and much lengthier, front-page article headlined “Russia’s Ultra yobs INFILTRATED”, which RT’s own rebuttal presented as its front page.

The longer article focused on a pair of interviews (not an “infiltration”) with apparently genuine Ultra leaders, one of whom was quoted as saying, “An England fan almost died in Marseille. It could be worse next summer. If the circumstances are right someone could get killed.”

RT singled this longer article out for particular attention, quoting the claim that “England fans could be KILLED at World Cup” immediately after the “What’s wrong with this story?” poll.

However, it did not then address the substance of the headline which it had singled out. Nothing in the rebuttal dealt with the death threat against English soccer fans: it focused on the misidentified brawl.

It is therefore open to question why RT saw fit to highlight the headline so prominently.

This may, perhaps, be accidental, or a tabloid-style attempt to include the most eye-catching claim without then following it up. However, RT’s coverage has recently featured a number of articles defending Russian fans’ behavior and reporting criticism or mockery of Western investigations into Russian soccer violence.

In parallel, RT’s sister organization, Sputnik, has even run an article on Russian fans under the apparently reassuring headline, “We’re not looking for trouble”, together with a promotional video— giving an indication of the Kremlin’s concerns about its reputation.

RT’s decision to start its rebuttal argument with a headline about hooligan threats, but not to address it, could therefore also be interpreted as an attempt to discredit the (apparently) accurate part of the Mirror report by associating it with the evidently inaccurate part.

Disinformation about disinformation?

The final four FakeCheck entries also recycle content, but they appear to have done so, not to expose disinformation, but to perpetuate it.

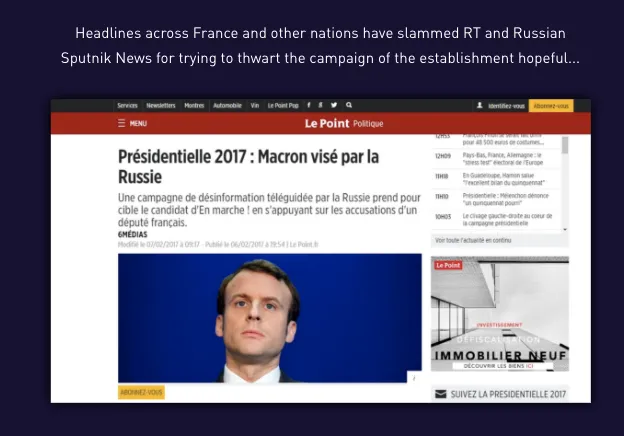

One concerned the accusation that RT and Sputnik have been biased in their reporting on French presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron, described by RT as the “election sweetheart” and “establishment hopeful.”

It rejected the accusation on the grounds that Wikileaks founder Julian Assange was in fact ultimately “to blame” for negative coverage of Macron, after he gave an interview to Russian newspaper Izvestia in which he claimed to be holding information on the Frenchman.

It is true that the initial accusations against RT and Sputnik came after they reported the Izvestia interview. However, as the DFRLab demonstrated in February, Sputnik France’s coverage of Macron has been systematically hostile, while its coverage of his main rival, Marine Le Pen, has been far more positive.

Far from exposing partial reporting, this entry appears to ignore it.

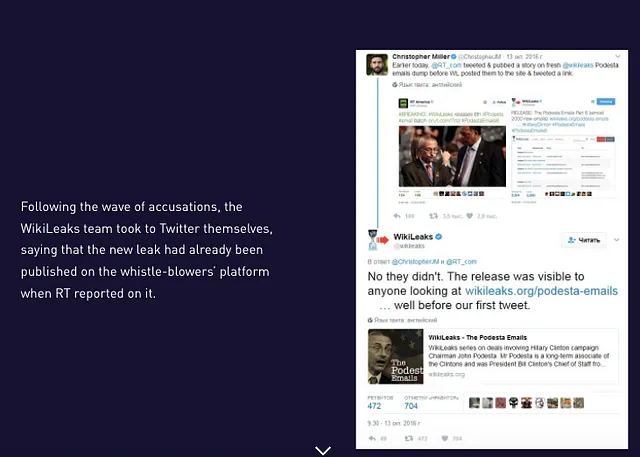

Assange also featured in another entry, which sought to prove that he has “no ties to the Kremlin,” after former US ambassador to the OSCE Daniel Baer referred to Wikileaks as one of the Russian government’s primary channels for leaking hacked data.

However, the only “evidence” RT provided to show that Assange has “no ties to the Kremlin” was the fact that Wikileaks and Assange had denied collusion either with the Russian government or RT.

Denials notwithstanding, Assange’s links to the Russian government and its media are well publicized, including his hosting a show on RT and his addresses to RT and Sputnik conferences. Furthermore, analyses published by US intelligence and by independent experts at ThreatConnect concluded that Wikileaks’ data dumps in 2016 came from Russian hacks. As such, it would take more than a denial to make RT’s “rebuttal” convincing.

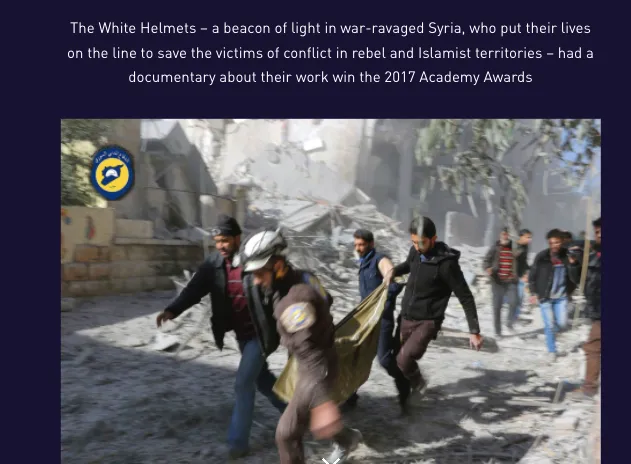

The final two entries concerned the conflict in Syria. One attacked the “White Helmets” rescue group, after a documentary about the group won an Oscar. The other attacked a number of Twitter and Facebook users who had posted “last messages” from Aleppo in the final days of the siege.

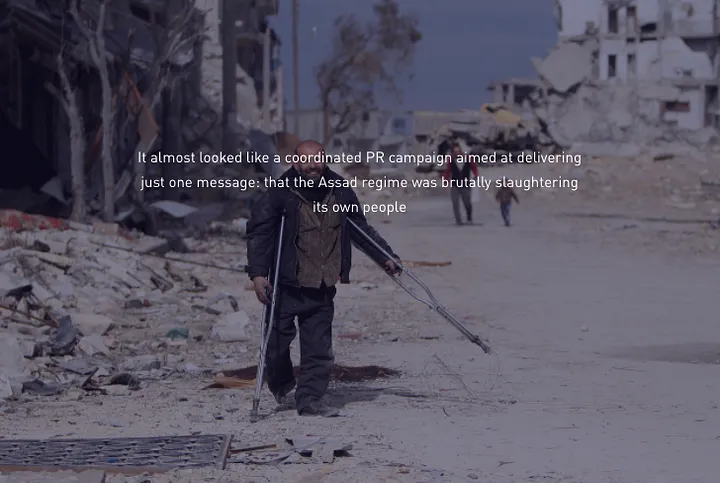

RT accused the “last message” posters of being biased, adding, “It almost looked like a coordinated PR campaign aimed at delivering just one message: that the Assad regime was brutally slaughtering its own people.”

It went on to argue that the posters were “activists engaged in an information war,” and accused two individuals of links to extremists, based on screenshots of social media accounts attributed to them.

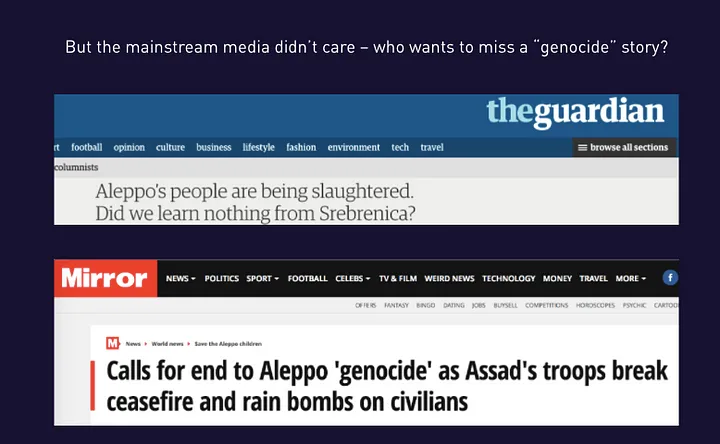

It concluded, “But the mainstream media didn’t care — who wants to miss a ‘genocide’ story?” As evidence, it presented a picture of two British newspaper headlines referring to “slaughter” and “genocide” in Aleppo.

There are two problems with this entry. First, the fact that the people posting “farewell” tweets may have been opposed to the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, or even supporters of radical groups, is irrelevant when considering what they tweeted.

As the first article in this series pointed out, “due impartiality” is a key value of journalism, but it applies to journalists reporting news — not to individuals tweeting about their emotions, even if they are activists.

A journalist reporting on the tweets could, in theory, be accused of violating the need to report with due impartiality, but only if it could be shown that they had not given due coverage to other voices.

Indeed, by implying that it would not be legitimate to report comments posted by opposition supporters, RT appears to be guilty of the very bias it accuses them of.

Second, neither of the headlines quoted by RT actually referred to the farewell messages. The Guardian article was an opinion piece by a survivor of the Srebrenica massacre, and did not mention the Aleppo social media posts at all (although a link to a video collage of them was appended to the online version of the article).

The Daily Mirror article quoted many sources, including the British prime minister, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Assad and the Russian Defense Ministry, and one post from Facebook — a suicide letter attributed to an Aleppo woman. The use of the word “genocide” in the headline was taken directly from a comment by British MP Lucy Powell.

For RT to imply that the Guardian and Mirror articles used tweets from “biased” sources to justify a “genocide” story is therefore simply wrong.

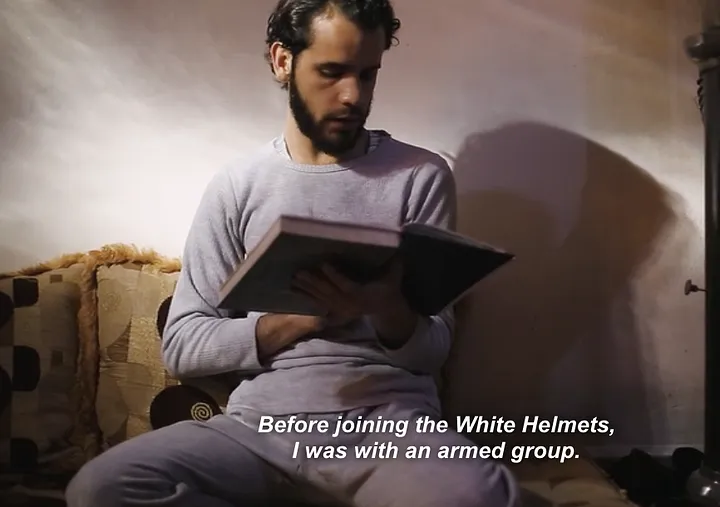

Similar treatment was given to the White Helmets after a Netflix documentary about them won the Oscar for best short documentary. The RT “FakeCheck” said there was something “wrong” with the claim that the White Helmets are “a beacon of light in war-ravaged Syria, who put their lives on the line to save the victims of conflict in rebel and Islamist territories” because the group had a “dubious” reputation:

It stated that individual members had been photographed alongside extremists, that the figures for the number of lives they had saved were “basically unverifiable,” and that they were funded by the US and UK governments, which “may suggest” that they are influenced by foreign powers.

However, none of those claims actually has a bearing on the statement that the White Helmets “put their lives on the line” to save people — which was a key part of RT’s complaint, and the essence of the Netflix documentary. RT even admitted that the group’s help “is for everyone: be it a person in distress or a hungry kitten in the street…while they are on duty, of course.”

Moreover, Netflix cannot be accused of covering up the connections between some White Helmets volunteers and the armed opposition: four minutes into the documentary, it interviewed a former tailor, Mohammed Farah, who confirmed that he spent three months fighting for the opposition.

It is therefore unclear what “inaccuracies, bias, misinformation, and outright falsehoods” the FakeCheck is meant to be revealing.

A clue to the possible reason behind the Oscar documentary’s inclusion can be gathered from the context of the Syrian conflict. RT’s comment on the “PR campaign” accusing Syrian regime forces of “brutally slaughtering its own people” is significant here.

As the Atlantic Council chronicled in its “Breaking Aleppo” report in February, a wealth of open-source evidence suggests that both the Syrian regime and the Russian air force committed war crimes during the siege of Aleppo, including targeting hospitals and using chlorine gas on civilians. A UN-mandated investigation published on March 1 confirmed that all sides in the conflict committed war crimes.

Among the main sources of evidence of individual airstrikes were opposition activists in Aleppo who posted images on social media, and the White Helmets, who published videos of their rescues, thereby documenting the exact location and nature of the strikes.

In fact, the RT “FakeCheck” entries on the Aleppo messages and the White Helmets appear to be a further attempt to discredit some of the key witnesses to Russian and Syrian regime war crimes in Syria.

Conclusion

RT’s “FakeCheck” has high production values, but low quality. Four of the articles it cites did include genuine “inaccuracies, bias, misinformation, and outright falsehoods,” but these were identified, and debunked, long before the project was launched, and RT played no part in the exposure.

A further four appear to commit the very errors they are meant to expose, combining inaccuracies and possible bias with irrelevant or insufficient evidence. Only one rebuttal genuinely appeared to expose a false report.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the FakeCheck project has not achieved a significant following online. As of March 22, it had gathered somewhat under 100 likes on social media.

The project appears to have three goals. One is to emphasize errors made by Western outlets; the second is to defend the record of the Russian and Syrian forces in Syria; the third is to defend the Russian government and its outlets more generally against accusations from the West.

In the word of Slate analyst Will Oremus in a recent commentary on the project, “And now, it seems, ‘fake news’ can mean ‘news that runs counter to the interests of Russian propaganda organizations.’” RT’s “FakeCheck” certainly seems to put the interests of the Russian state over the interests of accurate, impartial journalism.