The French election through Kremlin eyes

How the Russian state’s French-language wire portrays the French election

The French election through Kremlin eyes

Share this story

BANNER: Source: CC BY-SA 4.0 Teslar

Since early February, French centrist politicians have repeatedly accused the Russian government of interfering in the country’s presidential election, whose first round is scheduled for Sunday, April 23.

The campaign of centrist candidate Emmanuel Macron says it has been the target of repeated cyber-attacks from Russia, and of a campaign of “fake news” conducted by the Russian state’s main outlets, RT and Sputnik. In February, the DRFLab analyzed Sputnik France’s coverage and found that there was a distinct bias against Macron.

How have the Kremlin’s French-language outlets covered the election since? The DFRLab has analyzed their reporting to assess their portrayal of the main candidates: Macron, conservative François Fillon, and nationalist Marine Le Pen.

Much of RT France’s coverage has been adequately balanced: it has tended to report criticism of Macron, but at least mentioned the candidate’s own stance, albeit often briefly. Sputnik France, however, has continued to show a bias against Macron, compared with more favorable coverage of his main rivals.

Macron

Sputnik France has regularly criticized Macron. An editorial by commentator Jacques Sapir on March 6 described Macron as the “candidate of the financial and media oligarchy,” backed by a “political operation designed to promote a candidate with the profile of an ideal son-in-law, but no program, just as you promote a packet of washing powder or diapers.”

On April 10 the same author, a regular Sputnik editorialist (and interviewee on RT), wrote that Macron’s personality was “empty,” his language “falsely modern” and his status a “man of the past.” A third piece, on March 20, recycled the “diapers” line, but added that Macron had “no program (but alas, no lack of ideas, and they’re poisonous), no experience and no principles (but plenty of values, or rather valuables, in cash and property).”

Each article ended in a disclaimer saying that the responsibility was the author’s alone; but the decision of Sputnik to publish such harsh and repeated attacks on one candidate constitutes, in effect, an editorial policy.

On occasion, RT France has also slipped into hostile editorial language. For example, a report on a campaign rally on April 1 accused Macron of “letting himself get carried away by the atmosphere” at a rally in Marseilles; a follow-up article the next day was headlined, “Exalted, Macron howls (again) in Marseilles and makes Twitter laugh,” before listing three tweets mocking him.

Sputnik France has also accused Macron of having an unfair advantage in news coverage. On March 21, for example, an article on a presidential debate termed him the “darling” (chouchou) of broadcaster BFMTV; an editorial on February 6 called him the “darling” of the mainstream media more generally. Numerous separate articles, including on February 27, March 5, March 7, and March 28, repeated a claim that BFMTV was devoting more air time to Macron than to all his rivals combined.

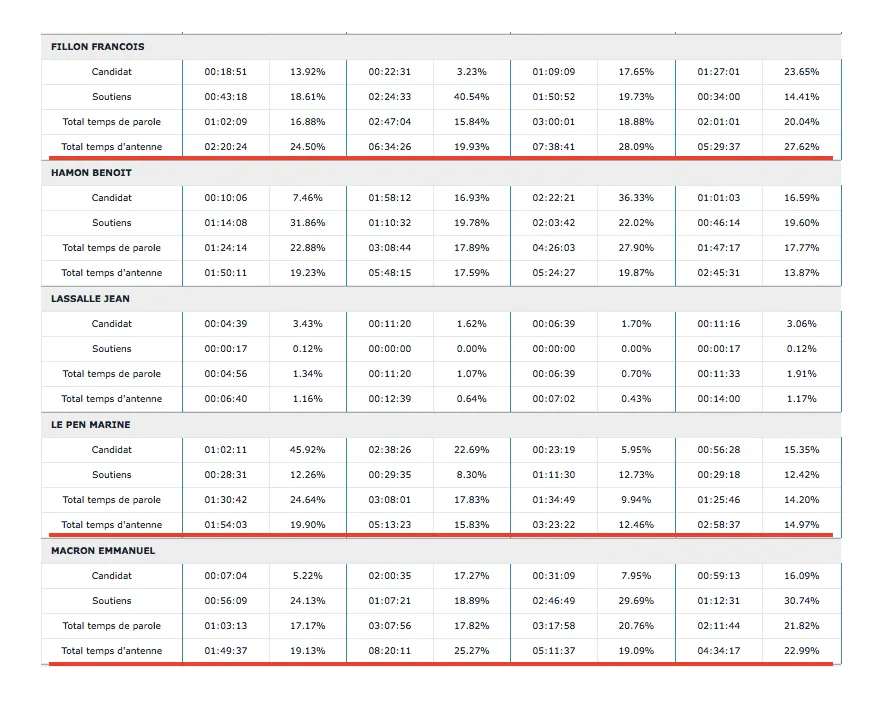

However, according to French telecoms regulator CSA, which regularly publishes statistics on the amount of air time devoted to each candidate, Macron actually received marginally less airtime on BFMTV than Fillon between the publication of official candidate lists and April 2 — although both men received significantly more than Le Pen.

More broadly, Sputnik France’s approach seems to have been to amplify accusations against Macron without giving adequate coverage of his response. For example, an interviewee on March 7 accused Macron of corruption. Sputnik devoted fourteen paragraphs to the accusations; the only reference to Macron’s position was contained in one of the many quotes from his accuser.

Similarly, the March 21 article on the presidential debate, held between the five leading candidates, quoted every one of them except Macron.

Not all of Sputnik France’s coverage of Macron was negative. A few articles could be construed as positive, as they documented the decision by leading French politicians to join his campaign (such as two articles on March 9). One even included an interview explaining Macron’s popularity among socialist politicians.

However, overall, the balance of Sputnik’s French reporting has been tilted against Macron.

Le Pen

Criticism, and in-depth investigation, of any politician is a vital role for the media, especially in an election season; however, the approach must also be balanced. This is especially true for state-sponsored outlets such as Sputnik.

In fact, Sputnik’s critical approach to Macron has not been matched by a critical approach to his main rival, Le Pen. She has benefited from broadly uncritical coverage, headlining her repeatedly, and playing down attacks.

On March 27 alone, for example, Le Pen was headlined in four successive articles: one reporting her increasing support in opinion polls, one quoting her as predicting the death of the EU, and two quoting her as attacking her rivals. In total, that day, Sputnik France listed eight articles in its “France” news section; of the other four, one attacked Macron, one supported Fillon and two were unrelated to the election.

Compared with the attacks on Macron, Sputnik’s coverage of Le Pen has been less critical, despite the fact that she is under investigation for allegedly fraudulent payments to staff during her time in the European Parliament.

One article on March 10, for example, quoted her parliamentary assistant accusing other parties of the same wrongdoing; nine paragraphs were dedicated to his comments, none to any other point of view. A follow-up article on March 26 reported six paragraphs of Le Pen’s comments, without giving other points of view. The Sapir opinion piece of March 6, which attacked the corruption scandals around Fillon and Macron, did not mention the case against Le Pen.

Other pieces have reported Le Pen’s stance without giving a balancing view. These include her accusations against the media on April 2, her speech against the EU on March 27, and her claim of secret state surveillance the same day.

Four days before the first election round, on April 19, one curious piece even headlined that Le Pen had declared her love for cats.

While trivial, this could just about be construed as news of the “human interest” sort if it had concerned a new revelation. In fact, the article was based one tweet from August 2016, a lightly satirical commentary on it from February, and a YouTube video published on March 1. The reason for releasing the story just days before the election is therefore unclear.

Not all reports were so favorable. One Sapir piece on April 17 analyzed the anti-euro stances of Le Pen and Mélenchon, arguing that both could only implement their policies by quitting the single currency straight after their election. Much of its rhetoric was aimed at the EU itself, claiming, for example, that “once France has affirmed its decision [to leave the euro], Italy would follow suit, swiftly followed by Spain, Portugal and Greece”; nonetheless, it can be viewed as critical of Le Pen.

Overall, however, Le Pen tended to benefit from more favorable Sputnik coverage than Macron.

Fillon

The case of Fillon is more nuanced. Sputnik France has, repeatedly, referred to the scandal which shook his campaign in late January when he was accused of fraudulently employing his wife. At times, this coverage has been negative — for example, the April 10 opinion piece attacking Macron, which also stated that Fillon “seems irredeemably tangled” in his scandals.

At others, it has appeared defensive — such as a separate opinion piece on March 9 which appeared to relativize the scandal, claiming that the false employment of family members is “truly a national sport at the [French] parliament” and complaining about insufficient media coverage of alleged Macron scandals.

Two articles on March 25 and March 26 reported accusations from Fillon, and one of his campaign staff, against French President François Hollande, claiming that Hollande was running a “black cabinet” which had bugged Fillon’s communications. Neither article mentioned Hollande’s position — although an earlier Sputnik piece, on March 24, had done so. This could simply be sloppy journalism, but it does nothing to enhance Sputnik’s reputation for balanced reporting.

An opinion piece on March 6 attributed Fillon’s slump in the polls to “media agitation” and praised a rally he held in Paris: “You can only underline the prowess in being able to mobilize so many people in just three days, despite the rain.”

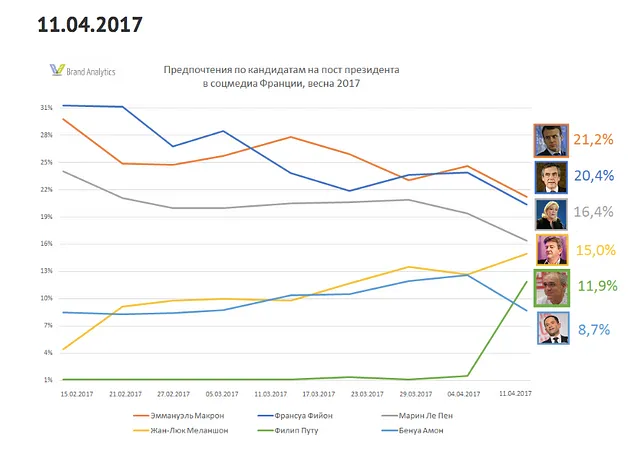

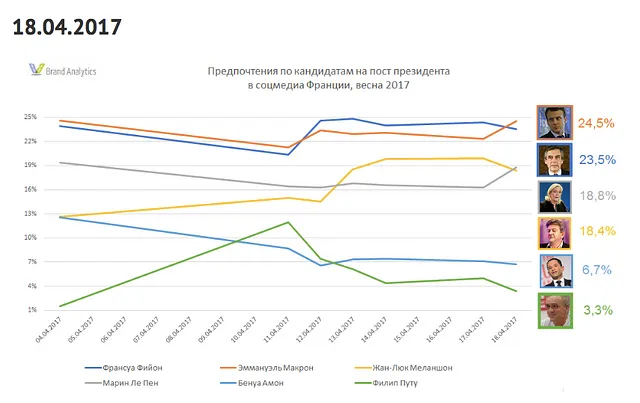

Most strikingly, since late March, Sputnik France has run a series of articles predicting a Fillon victory, against a background of gradually recovering poll numbers. All of these were based on online surveys conducted by a Moscow-based company called Brand Analytics, which specializes in social media surveys.

Sputnik ran stand-alone articles on Brand Analytics’ findings on March 29, April 4, April 14, and April 17. In three of the four, it reported Fillon as being the favorite; in one, on April 4, it headlined that “The second round will be between Fillon and Macron”, before confirming in the third paragraph that Macron was in fact in front.

There are two questions about these articles and studies. The first concerns Brand Analytics’ methodology, which was criticized by the French Commission des Sondages (Commission for Opinion Polls) in a rare public statement on March 31.

The Commission des Sondages stated that the Brand Analytics study could not be considered, or reported, as an “opinion poll” because it was based on social media analysis, not the polling of a representative sample — the French legal definition.

On April 2, Sputnik France responded with a long article defending Brand Analytics’ methods.

The article quoted the director of the Brand Analytics analytical centre, Svetlana Krylova, as saying that their study was “more precise” than traditional polls because it focused on social media posts:

“Unlike traditional polls, we work in real time and (…) can analyze the answers from people who are really interested (who will go vote, sent a text etc.). (…) All we do is ‘listen’ to the words of people on social networks.”

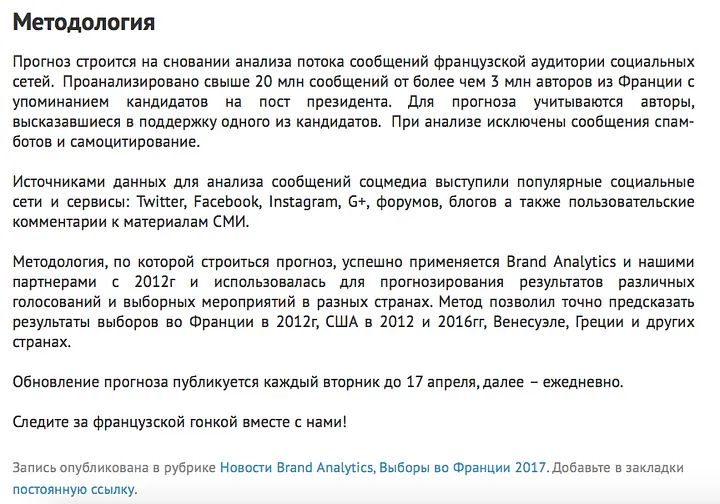

Brand Analytics itself confirmed this on its own blog page, saying that “The forecast is based on the analysis of the flow of messages to the French audience of social networks. More than 20 million messages from more than 3 million authors from France have been analyzed with reference to candidates for the presidency. For the forecast, the authors who supported one of the candidates are considered.”

It gave its sources as “Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, G +, forums, blogs, and user comments on media materials.”

It claimed that “spam bots” were excluded, but gave no indication of how this was achieved; nor did it indicate the margin of error for its findings.

Social media analysis is, of course, an increasingly crucial way of studying the opinions of specific interest groups; but it is, by definition, limited to those who are active on social media. The Brand Analytics study was further limited to those commenting on politics.

As the Commission des Sondages pointed out, the Brand Analytics studies cannot be considered as representative samples of nationwide voting intentions. If their methodology is sufficiently robust, the studies could shed light on the voting behavior of politically interested social media users; but this requires significantly more information on the exact methods used.

The second question concerns Sputnik’s use of the surveys. The studies which it reported were not the only Brand Analytics surveys during the period. The company also published findings on April 11, 12, 13, 18, and 19. Two of them — on April 11 and April 18 — put Macron in the lead, reversing earlier apparent Fillon gains. Sputnik did not report these.

It is, of course, an editorial decision what to leave out; but by leaving out some surveys, Sputnik created the impression that Fillon consistently led the pack in Brand Analytics’ findings. This was not the case.

This was not the first time that Sputnik had made such an editorial choice on polling data. On March 23 and 24, for the first time, two separate polls put Macron in first place for the first round, ahead of Le Pen. The shift was reported by mainstream French media, such as Paris Match and Midi Libre.

Sputnik’s reporting on March 23 headlined that “The gap between Le Pen and Macron is closing,” before acknowledging in the body of the text that Macron had in fact overtaken. On March 24, Sputnik headlined, “Le Pen still in front in the first round, according to the latest polls.”

Despite the headline, the March 24 article only mentioned one poll, which put Le Pen in the lead. It failed to mention either poll which had put Macron in front.

Yet another article, on March 9, headlined, “Fillon would beat Le Pen in the second round, if he got there.” This was true as far as it went, but relegated to the fourth paragraph the fact that Fillon was polling 21 per cent in first-round support, compared with 25 per cent for Macron and 26 per cent for Le Pen.

Taken together, these incidents suggest that Sputnik has an editorial preference for surveys which emphasize the popularity of Fillon and Le Pen, and a reluctance to give too much coverage to polls which show Macron doing well.

Conclusion

Sputnik France’s coverage has a number of political biases. It is broadly critical of Macron, while being significantly less critical of Le Pen. Its coverage of Fillon has been more nuanced, but has tended to favor him, especially in its reports on his election chances.

This stance fits the three candidates’ positions on Russia. Fillon and Le Pen are both seen as pro-Kremlin; Le Pen even visited Moscow in late March. Macron is far more pro-EU, pro-Atlanticist, and Russia-skeptic. Thus for the Kremlin, a victory for either Fillon or Le Pen would be better than a Macron win.

It also indicates the possible trend of Russian information activity between the first round, on April 23, and the run-off, on May 7. If Fillon and Le Pen progress to the second round, the Kremlin’s media are likely to report in a balanced way. If, however, the run-off pits Macron against either of his rivals, more bias can be expected.