The Many Faces of a Botnet

How a single network of fake accounts claims many identities

The Many Faces of a Botnet

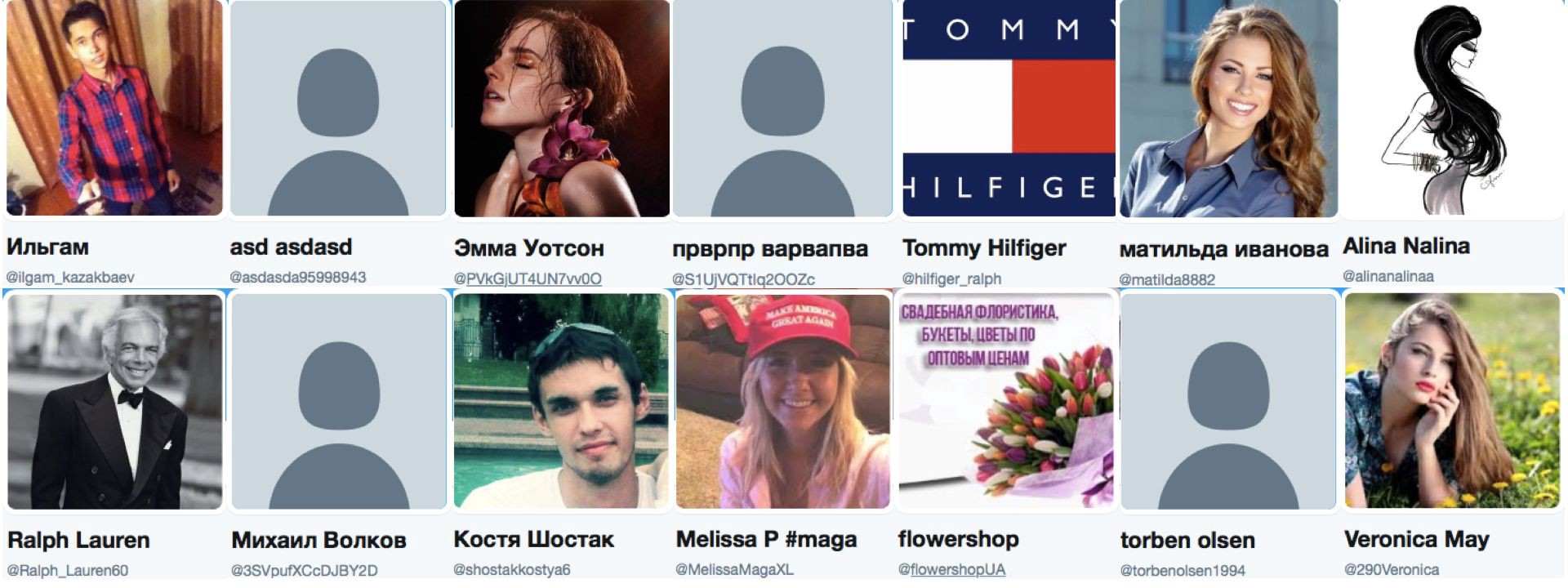

BANNER: Some of the many avatars used in the botnet.

On May 5, a Twitter account which had posted just twelve times in its lifespan tweeted a complaint about a Green Card application. Within days, the tweet had recorded over 6,000 retweets from accounts with identities as varied as Central Asian men, US-based supporters of President Donald Trump, Russian models, and Ukrainian florists.

The overwhelming majority of them appear to be fakes: automated “bot” accounts set up to amplify other people’s posts.

These bots are not particularly aggressive: the majority post a few times a day at most. Nor do they appear to play a political role. They are noteworthy for the size of the network — over 6,000 accounts — and the range of identities which the accounts within the network claim.

It is worth analyzing this network as an illustration of the sheer range and variety of identities which bot herders can adopt as they create their tools — and the ease with which it is still possible to create massive herds.

Source and tweet

The tweet in question was posted on May 5 at 08:21 UTC by an account with the alphanumeric handle @p79252228585.

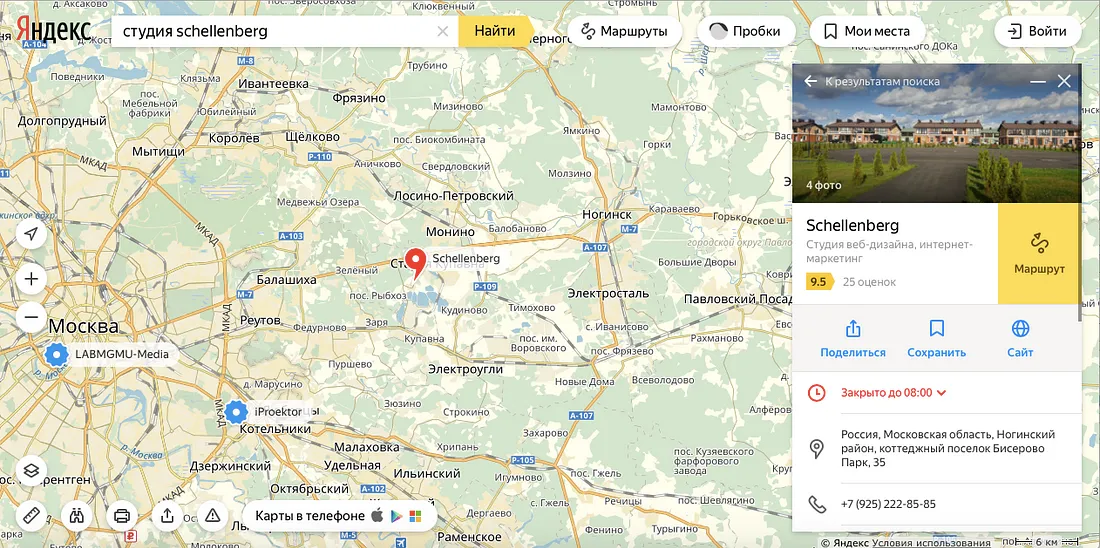

The account’s screen name is “Schellenberg.” It joined Twitter on October 13, 2015. As of May 22, 2017, it had posted 27 tweets, and was following three users. Despite this very low level of activity, it had 13,228 followers.

The combination of an alphanumeric handle, single screen name, very low level of tweets and very high number of followers raise the question of whether this is itself a fake account.

However, the profile includes a link to a web design and Search Engine Optimization (SEO) company, schellenberg.pro, registered in the Noginskiy district of the Moscow region to Gunther Heinrichovich Schellenberg (Гюнтер Генрихович Шеллинберг). The company is listed on Yandex Maps at a location between Moscow and the district capital, Noginsk.

A number of the Schellenberg account’s tweets also advertise the company.

On May 5, the account posted a tweet complaining about its difficulties in the US Green Card lottery. This included a screen grab of a letter to Schellenberg from the Kentucky Consular Center, giving the same address as in the web profile.

A reverse image search of the profile picture showed that it has been used in a number of other social media, including Odnoklassniki, YouTube gaming, and Google+ (two accounts), all attributed to Schellenberg and his studio.

It is not the purpose of this article to analyze Mr Schellenberg’s Green Card travails; however, the information given above does suggest that the Schellenberg account has a genuine identity behind it.

Replies and amplifications

What is of interest is the pattern of retweets which followed. According to a machine scan conducted on May 22, it was retweeted 6,444 times over a period of seventeen days, by a total of 6,444 users. By contrast, it only received three replies, and some 500 likes. This ratio strongly suggests that the retweet traffic was heavily influenced by bot traffic.

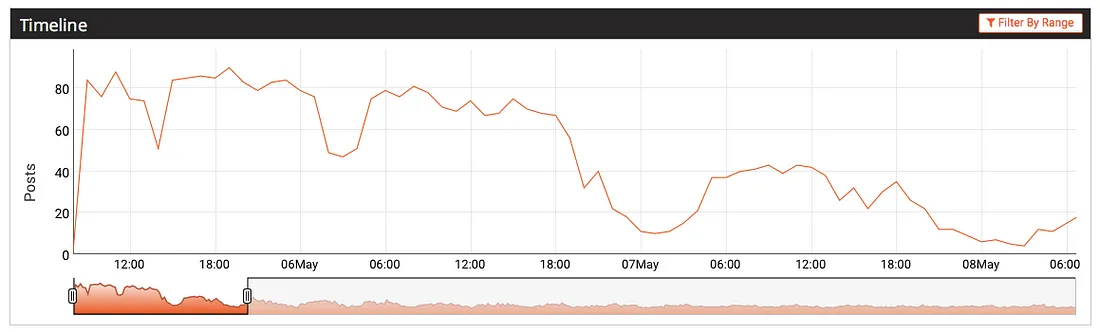

The speed of retweeting is also suspicious. It took forty minutes for Schellenberg’s tweet to achieve its first retweet; however, thereafter its climb was very rapid, up to a rate of some 80 tweets per minute, and it stayed close to or at that rate for the following 36 hours, dipping down to some 50 tweets per minute in the early hours of May 6.

This explosive growth to a high rate of tweeting which is then sustained around the clock is more characteristic of automated, bot-driven traffic than of organic growth.

The faceless

That impression is confirmed by the number of accounts which were faceless — accounts with no avatar image, only a blank space provided by Twitter.

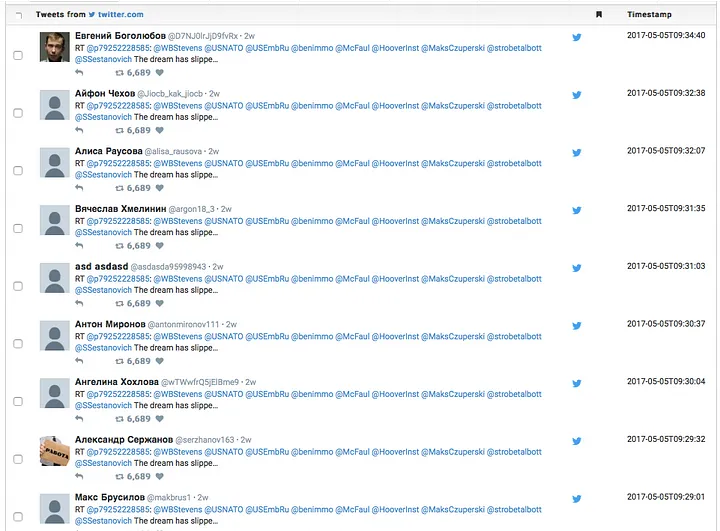

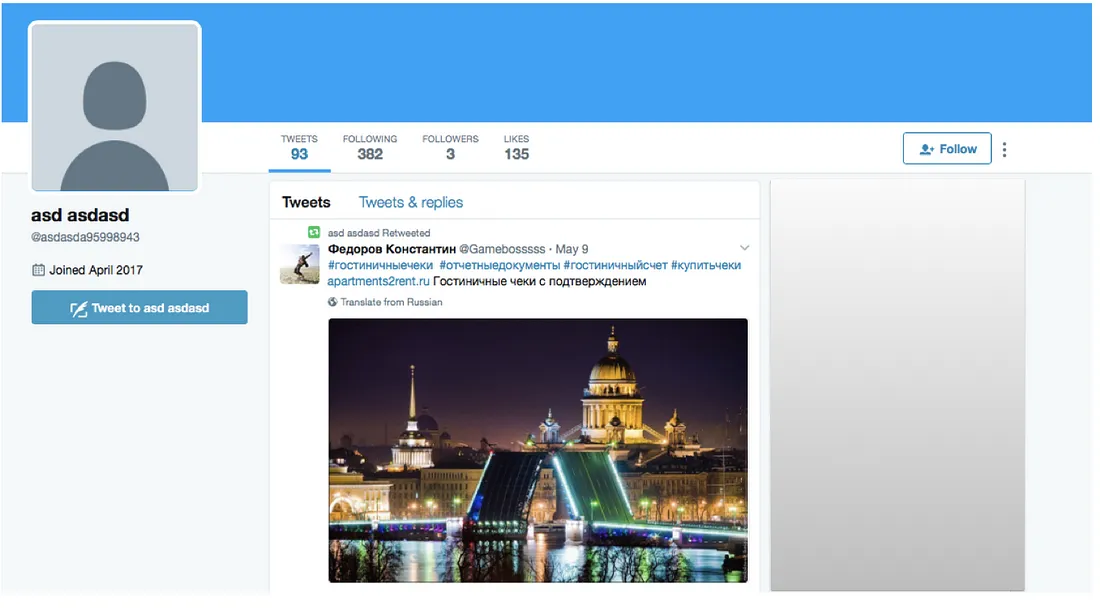

Some of these accounts made little attempt to appear as if there was a human behind them. @asdasda95998943, for example, gives no picture or background, and its username is clearly a repeat of the letters ASD from the left-hand side of the keyboard, together with an eight-digit number.

Created on 17 April, all its posts save one are retweets, largely of commercials; the one exception is a share of a website headline advertising bitcoin.

Moon Bitcoin – The bitcoin faucet where YOU decide when to claim! https://t.co/Pd4EnmATYt #bitcoin #faucet с помощью @Moon_Bitcoin

— asd asdasd (@asdasda95998943) April 19, 2017

The same applies to the account @S1UjVQTtIq2OOZc, screen name “прврпр варвапва.” Again, it is faceless; its account handle is an alphanumeric scramble more likely to be computer-generated than user-generated; its screen name is a scramble of four adjacent keys of the Cyrillic keyboard (equivalent to DFGH on a QWERTY keyboard); all its posts are retweets.

Accounts such as these are very obvious bots. Their prevalence in the overall pattern indicates very strongly that this is a botnet set up to amplify others’ posts, without much attempt to disguise the fact.

Stars (and Star Wars)

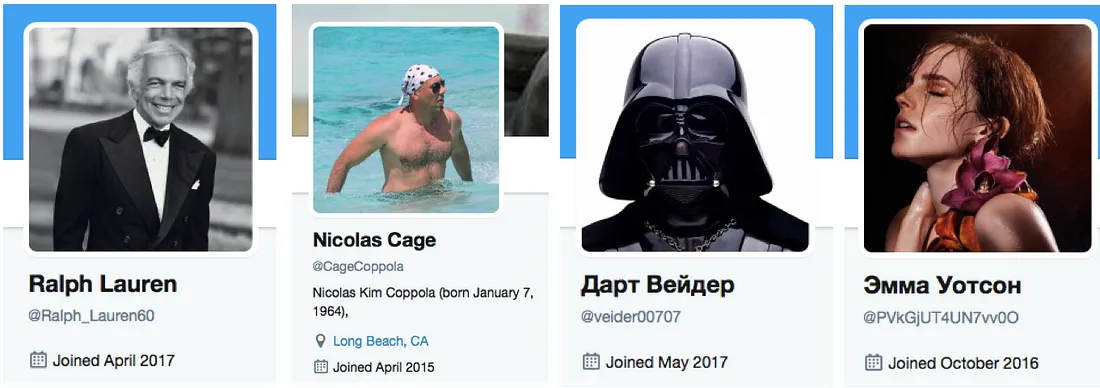

Equally obvious are the accounts which take the names and images of cultural icons. Actress Emma Watson, actor Nicolas Cage, fashion legend Ralph Lauren, and Star Wars villain Darth Vader all feature in the accounts which retweeted Schellenberg; they also posted a wide range of commercial and / or pornographic retweets, largely (but not exclusively) in Russian.

There is no indication that these were meant as serious attempts to impersonate the people whose names and images they stole; they rather appear like the work of a bot creator who found it easier to borrow stars’ names and images than to make up more subtle fakes.

Fake faces: Russian men

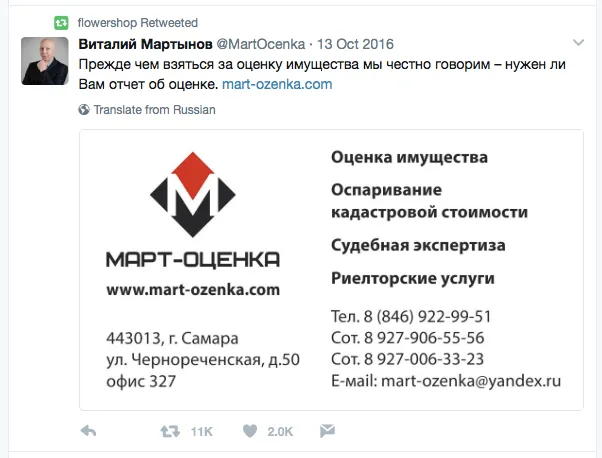

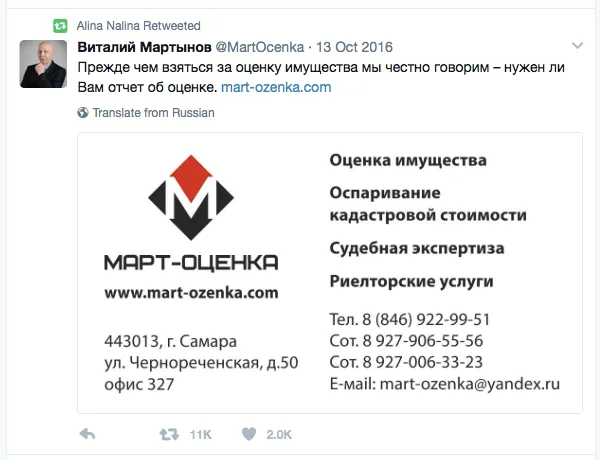

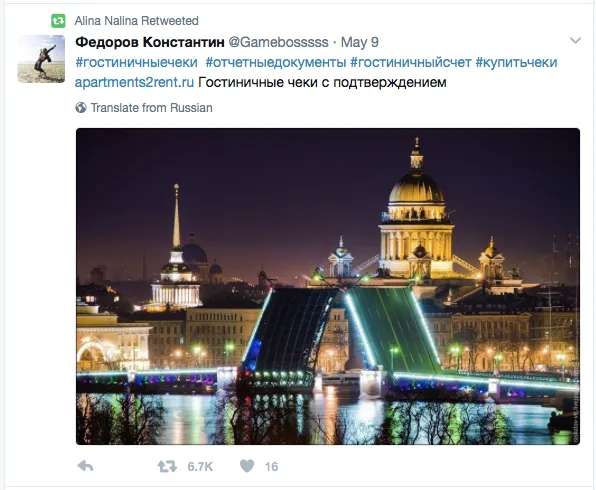

Some of the accounts made more of an effort. @eVgenEvtushenko, for example, which was created on May 20, at least had a cartoon image for an avatar, and a name in Cyrillic (Евгений Евтушенко) consistent with its screen name. However, of its sixteen tweets in the period to May 22, fifteen were retweets; the one exception was a simple “Hello world” posted on its creation. Most of the retweets were commercials, including the following two — one advertising a service for drawing up real-estate documents, the second a property valuer’s in Samara:

The account @shostakkostya6 was one step better engineered, featuring a genuine photo as its avatar image; its handle and screen name (Костя Шостак) matched one another.

However, its activity pattern gives no indication of a person behind the account. It was created on March 12; by May 22 it had posted 108 retweets, but not one original tweet. They included the same pair of commercials:

The account @Sanchos3 (Саша Соколов) was older, created on November 26, 2013. Its thirty-five posts since then were a combination of retweets and commercials for various sorts of online coins and games, shared from websites:

Yet again, its recent retweets include the same pair:

These commercials can be used as markers to track this network of accounts. Many of the accounts identified throughout this report retweeted many of the same posts, including a high proportion of pornographic content; but these two in particular are among the most frequently-used decent ones.

Some of the male names in the network suggested a non-Russian ethnic origin. The account @ilgam_kazakbaev, for example, has a Central Asian name, and gives its location as Sibay, in Russia’s Bashkortostan Republic. It was created in May 2016, and has only posted retweets, mostly commercial, and including the same advert for real-estate services.

The account @nar_aliakbarov (screen name Nariman Aliakbarov) also has a Central Asian tone, and even shares posts from Kazakh media, but the overwhelming majority of its posts are retweets of commercials, including in Russian, Spanish, English, Polish and Korean.

All of these appear to be bots, with a greater or lesser degree of disguise, set up to amplify commercial messages.

Russian girls

Much the same can be said of the many accounts which claimed a female identity.

Some were barely masked. Two accounts, @aalinanalina (created in January 2016) and @alinanalinaa (May 2017), had all but identical handles, similar cartoon avatar images and a similar pattern of posts.

Neither is particularly active: the older account, @aalinanalina, had posted 84 tweets by noon on May 23, all retweets and mostly commercials; the younger, @alinanalinaa, had posted 72, all retweets, mostly commercials.

Both accounts’ posts included sharing the two commercials identified above:

Others used avatar photos, rather than cartoons, and names consistent with their handles, such as @matilda8882 (screen name матильда иванова) and @daha4111 (Дарья Филлиповна).

However, the account attributed to Darya Philippovna took its avatar from a wallpaper shot of singer Katharine McPhee, while the account called Matilda appears to have taken its image from a Texas real-estate agent:

Yet again, both accounts posted both retweets from the Russian real estate agents, and a number of other posts in common; neither posted any individual tweets at all.

The Trump follower

One particularly striking account claimed to be a fervent supporter of US President Donald Trump. Called “Melissa P” (handle @MelissaMagaXL), it was created on May 12, and features classic iconography of the pro-Trump online movement, including a red cap with the phrase “Make America Great Again,” the slogan MAGA, the declaration that she is “White and proud,” and a number of revealing images.

Its earliest posts were in English, including a list of desirable qualities in a date and praise for actress Megan Fox. However, both were taken word for word from other users (@betzolivia and @ittzkait). Its avatar image is identical with one posted by Twitter user @prod4Trump on June 26, 2016.

Most of its other posts were retweets in Russian; one was a retweet in Arabic. Yet again, two of the retweets were of the posts which can be used to mark this network:

This behavior is hardly the classic pattern for a fervent Trump supporter in the United States; what it does show is that this account was created with rather more of an effort to make its appearance and early posts consistent.

Foreigners

Other accounts also posed as foreign, largely English-speaking, men and women, without changing their main language from Russian to English, and often taking their images from other internet users.

For example, the account @AmandaF57437892 claimed the name of “Amanda Fowler,” with the avatar of a blonde woman in a fur hood. Created in March 2017, it only appears to post retweets, mostly of Russian commercials, but also in English, Spanish, Italian and Arabic; these included the two marker commercials. The photo itself appears to have been taken from the Instagram account of fashionista Lucy Williams.

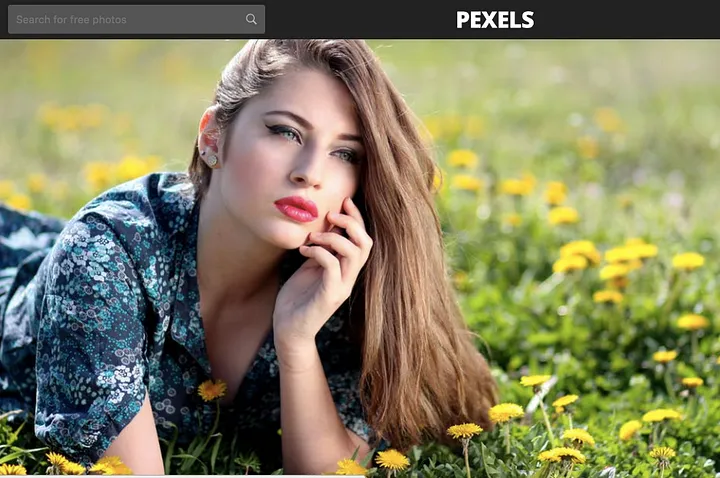

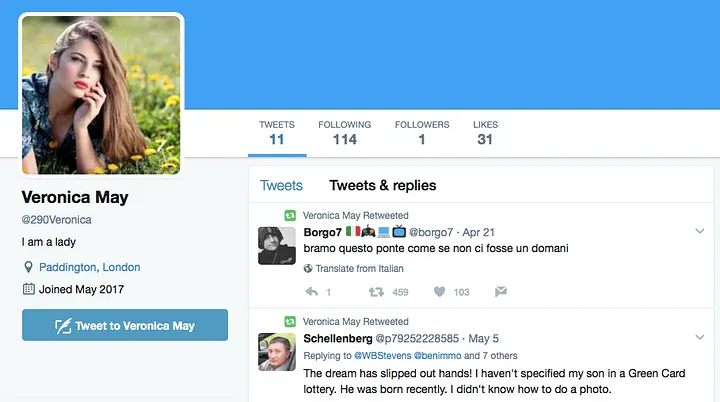

The account @290Veronica, tagged to Paddington in London and giving the name “Veronica May,” was created on May 1 and posted eleven retweets (no original tweets) — four in English, including the Schellenberg one, five in Russian, and one each in Italian and Korean. Its avatar image was taken from online stock photo provider Pexels, which does not require attribution or license for publishing.

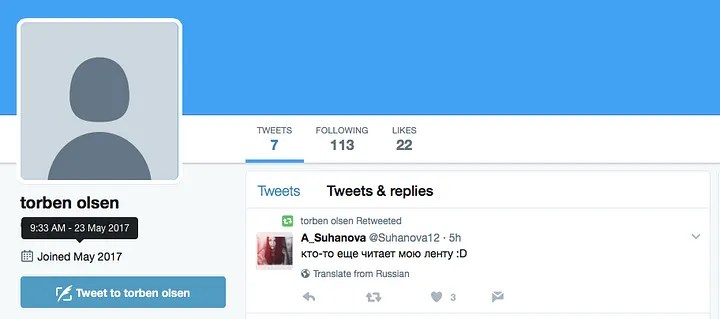

Less care appears to have been taken to give accounts with male foreign names appropriate camouflage. An account created on May 23 with a male name — @torbenolsen1994 — seems to fall into this category. The screen name, Torben Olsen, is Nordic; as of May 23, the day of its creation, it had posted three times, all retweets, one each in English (the Schellenberg tweet), Russian, and Arabic.

It has no avatar image, increasing the appearance of a bot.

By comparison, the account @RCocobano (Raul Cocobano) used for its avatar an image of the Norse god Thor, posted an overwhelming proportion of retweets, mixed languages (mostly Russian, but also English, Italian, Hindi and German), and retweeted the same two real-estate tweets which mark this network.

Businesses

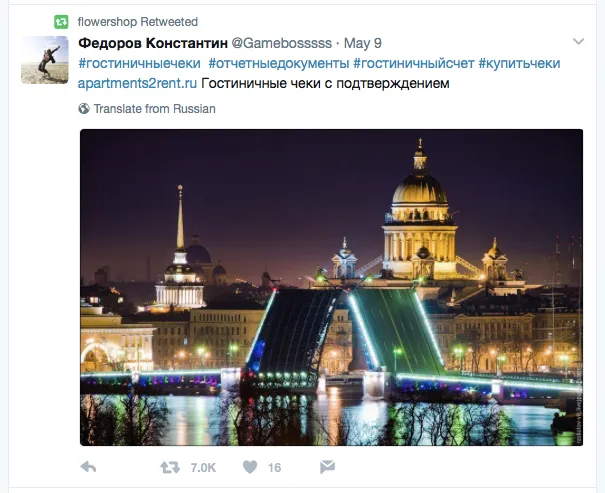

The final group of apparent bots in this network involves accounts posing as businesses of various kinds, but not sharing tweets linked to their business.

Two such accounts posed as music businesses, @melodyzrecords and @TechnologicRec. Far from posting on music, they shared the same mixture of retweets — including the real-estate retweets which mark this network — as all the other accounts above.

So, too, did an apparent flower shop in Ukraine, an account named after the US state of Vermont, an alleged betting account and an ostensible gadgets account.

None of these shared posts which focused on their ostensible area of activity. The Ukrainian florist, for example, barely mentioned flowers or Ukraine, but did mention the Samara and St Petersburg real-estate services:

This is hardly plausible behavior for a genuine business. It is far more likely to be the marker of yet another subset of the network of bots.

Conclusion

These accounts have many variations in their screen names, images and apparent identities, but the evidence indicates that they are all bots — retweeting rather than tweeting, mixing languages and themes, and predominantly amplifying commercial messages. The strong likelihood is that this is a botnet, likely for hire, and used to provide amplification for other accounts.

That is not necessarily to say that the accounts amplified are aware of the fact. One tweet amplified by many of the accounts in this network was a post from US-based tech reporter Aaron Sankin.

Under a little-known provision of the AHCA, if you get 3 million retweets, you get health insurance.

— Aaron Sankin (@ASankin) May 9, 2017

Sankin’s tweets usually receive relatively low numbers of retweets, in the double digits. The botnet amplified that tweet by retweeting it over 1,000 times, but not boosting its number of likes — leading to some amusement on Sankin’s part:

tfw a whole bunch of Russian bots RT your tweet because reasons and your ratio makes zero sense pic.twitter.com/lwL8znkwMc

— Aaron Sankin (@ASankin) May 10, 2017

Two things about this network are significant. First is its scale. By May 22, as we have seen, over 6,400 accounts had retweeted Schellenberg’s tweet. All those examined in detail for this article bore clear signs of automation; many, many more were faceless, alphanumeric accounts. It is therefore legitimate to assume that, even if some genuine accounts also shared the tweet, the bots can be numbered in the thousands.

Second, it is blatant. Many of the accounts are obvious fakes; others claim false identities; still others use pirated photos. All post much the same content, including many identical retweets, with few or no original posts. The main difference from other botnets is the slow rate at which they post — a few retweets a week, rather than hundreds.

Together, these factors suggest that, despite all Twitter’s attempts to weed out botnets, it is still relatively easy to create a network thousands strong. The main limitation on their creation and use remains the creator’s own creativity, rather than any technical efforts to hamper bot usage.