Into the Uncanny Valley of Fake News

A case study in how a cluster of websites managed to pose as legitimate sources and, despite being exposed, got away with it

Into the Uncanny Valley of Fake News

Share this story

BANNER: Some of the doppelgänger sites, and the fake news stories they have published.

On August 13, a website posing as the site of British daily The Guardian published a fake story accusing the UK and the U.S. of plotting to break up Russia. The story was quickly debunked, and an investigation by BuzzFeed News revealed that this website was one of a cluster of doppelgänger sites set up to mimic reputable outlets, not all of which are Russia-centric.

Despite the exposure, Russian media and social media users continued to amplify the article, implicitly accusing The Guardian of a coverup. The same pattern applies to other fake stories launched by this cluster of sites.

These cases once again show the tenacity of fake news stories, even after they have been exposed to the mainstream, and especially when they serve a particular political purpose.

The Guardian case

The story about the Guardian-impersonating website broke on August 13, after its article purporting to be a Guardian interview with Sir John Scarlett, a former head of the UK intelligence service MI6, appeared online. The article has since been deleted, but it was archived the same day it was published.

The fake article claimed that MI6 and the CIA had plotted to break up Russia and had instigated the so-called “Rose Revolution” in Georgia as part of the plan, but that Russian President Vladimir Putin and an “iron fist of Moscow” had defeated the plan.

The site was all but indistinguishable from that of The Guardian. It used the same font, palette, headers, and logos, and linked to genuine Guardian articles. Its URL — theguardıan.com, using the Turkish letter “ı” in place of the Roman “i” — was almost indistinguishable from the genuine theguardian.com. (The registered domain name, as demonstrated by BuzzFeed News, was theguardan.com; the letter “ı” was coded in.)

However, the technical and design skills were not matched by linguistic competence. The text itself was riddled with errors, starting with the first sentence — “Just nine years ago on such days…” — and including an inability to use the word “the” correctly: “The first step was establishment of military and intelligence bases.”

The fake was rapidly exposed. On August 13 at 10:20 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), Moscow-based journalist Marc Bennets tweeted that someone “appears to have hacked the Guardian website.” Within minutes, Twitter user Zhan Li tweeted to point out that the URL was a copycat using the Turkish character.

Underlining the incompetence of the text, both Bennets and Twitter user @Psyklax (an English teacher) pointed out the linguistic errors:

It's weird. If you can hack that well, why not also get someone who can write normally in English?

— Marc Bennetts (@marcbennetts1) August 13, 2017

Christ, the grammar, it's painful. Wonder if/when they'll notice.

— Paul Coates (@Psyklax) August 13, 2017

A few hours later, Poland’s former foreign minister Radosław Sikorski tweeted about the fake to his 972,000 followers. Soon after, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Anne Applebaum followed suit, tweeting to her 179,000 followers.

active measures, 2017. check out this article from "https://t.co/808SsKZYeJ." it even links back into the real thinghttps://t.co/aByuQwT904

— Anne Applebaum (@anneapplebaum) August 13, 2017

Within two hours of Applebaum’s tweet, according to analyst Grant Stern, the fake page was shut down.

Tracing the network

Perhaps by virtue of its attack on The Guardian, the fake story was the subject of intense reporting by mainstream Western outlets. In particular, journalists Craig Silverman and Jane Lytvynenko of Buzzfeed located a Russian-language website, pravosudija.net, which had run a translation of the article and had attributed it to a translator named “Addilyn Lambert.”

By analyzing the pravosudija.net translation, as well as other articles attributed to the same translator, Silverman and Lytvynenko identified a cluster of other fake stories. All were Russian translations from other websites that posed as genuine news outlets like The Atlantic, Al Jazeera, and Haaretz.

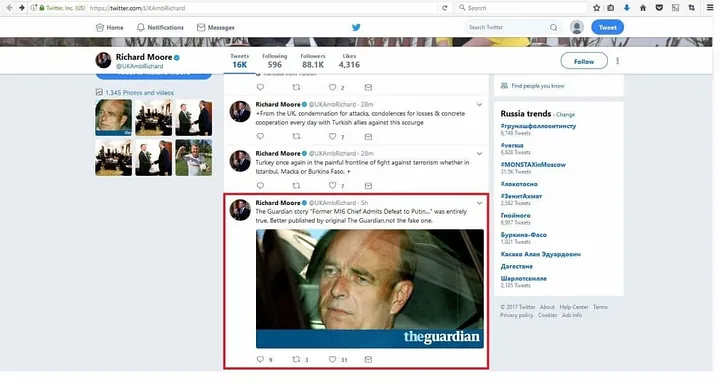

They also found a Facebook page associated with the purported translator. When they inquired into the veracity of the “Guardian” story, the “translator” (whose identity could not be verified) provided a screenshot of a tweet apparently sent by UK Ambassador to Turkey Richard Moore:

The tweet reads: “The Guardian story ‘Former MI6 Chief Admits Defeat to Putin…’ was entirely true. Better published by original The Guardian,not the fake one.”

Silverman and Lytvynenko pointed out that no such tweet appeared on the ambassador’s timeline, and concluded that it “appears the almost certainly fake tweet was inserted [into an image of] the ambassador’s timeline in place of a real tweet that contained an image.”

The song is ended, the malady lingers on

Thanks to this rapid and high-profile debunking, the English-language version of the article enjoyed little spread online. Facebook deleted all posts that included the original link, but a number of users shared posts linking to the archived version of the article. These included posts made to the groups Veterans For Peace and Politics, Freedom, Democracy and Grassroots Activism.

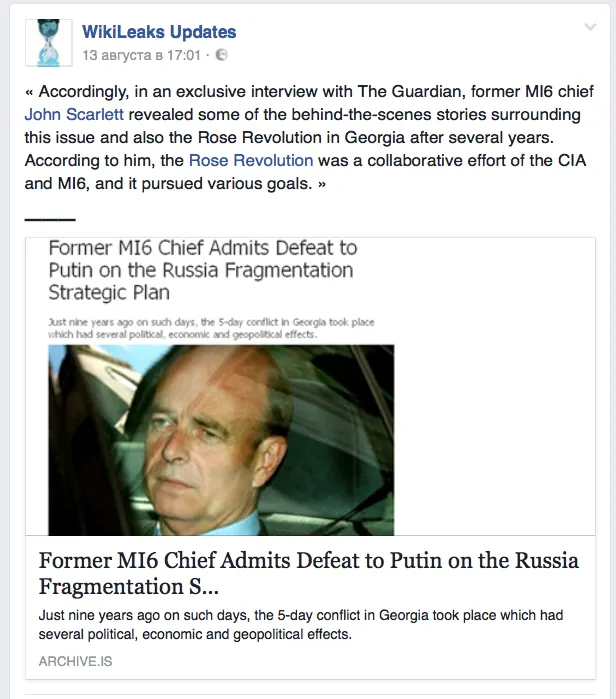

The most eye-catching was a post by the Facebook account WikiLeaks Updates, which shared the archived version of the article, and which highlighted the quote attributing the Rose Revolution to the CIA and MI6.

The WikiLeaks Updates page attributes itself to another Facebook page, Political Fail Blog, and appears not to be related to WikiLeaks itself; WikiLeaks itself had made a post exposing the fake story an hour before the WikiLeaks Updates Facebook page had shared the link.

Also curiously, this post, and many others on the WikiLeaks Updates page, used the symbols “«” and “»” for quotation marks, a system used in Russian and in a number of other European languages, but not in English.

Despite comments from users elucidating the article as fake, the post had not been taken down by August 16.

On Twitter, a handful of diverse English-language accounts shared the story. These accounts included @mortymer001 (apparently a monetary blogger), @JohnHewlin (apparently a Newfoundlander), and @FIgdari (apparently a critic of U.S. President Donald Trump, and probably a bot, to judge by its high proportion of retweets).

The most significant of these accounts was an Arabic-language account called @alqazm_alarabi, which tweeted the story on August 14 with the comment, “The Guardian story ‘Former MI6 Chief Admits Defeat to Putin…’ was entirely true. Better published by original The Guardian,not the fake one.” This is word-for-word the same text, and the same image, as that of the tweet Silverman and Lytvynenko found inserted into the screenshot of Ambassador Moore’s feed; it even misses the same space after the final comma:

This is probably the source of the faked image “Addilyn Lambert” provided to Silverman and Lytvynenko. The account also appears to have a further link with the cluster of fakes identified by BuzzFeed — more on this point below.

Unlike the English-language version, the Russian-language version of the fake story continued to spread well after its having been debunked. Some outlets misreported the fact that the fraudulent site had been taken offline, instead claiming that a genuine Guardian story had been deleted, thus implying that the interview had been a real one that was subsequently covered up. At least four versions of the story made the rounds.

The translation posted on pravosudija.net was deleted from the website once it was exposed as a fake; however, it is still viewable on Pikabu, a popular Russian curating site. This version of the article was also shared on the Russian curating sites yaplakal.ru (on August 13), glav.su (also on August 13), and jediru.net (on August 15), and on the pro-Ukrainian-separatist site antimaydan.info (on August 13).

The Russian TV outlet REN TV reported a summary (not a copy) of the story on August 15, claiming that “the article was deleted from the [Guardian] publication’s website, but is still accessible for view in a cache.” The REN TV article was reproduced almost word-for-word, but minus the important sentence about the deletion of the article, by fringe Russian sites rusnext.ru and infopolk.ru.

None of these reproductions had been deleted or corrected by August 16.

A third variant was published by online the outlet politonline.ru, which made no mention of the deletion, but commented, “Whether this is openness, or an intentional canard by the Guardian, is not very clear, but overall, the very intentions voiced in the article, such as the dismemberment of Russia and its collapse, sound serious enough to be listened to and taken into consideration.”

This version, in turn, was republished by the fringe site x-true.info; according to a comment appended to the article, it was also published by the mainstream outlet pravda.ru, but quickly deleted. A Google search on the Pravda site confirmed that an article about the fake interview had been posted there around 08:30 UTC on August 16, but was no longer live.

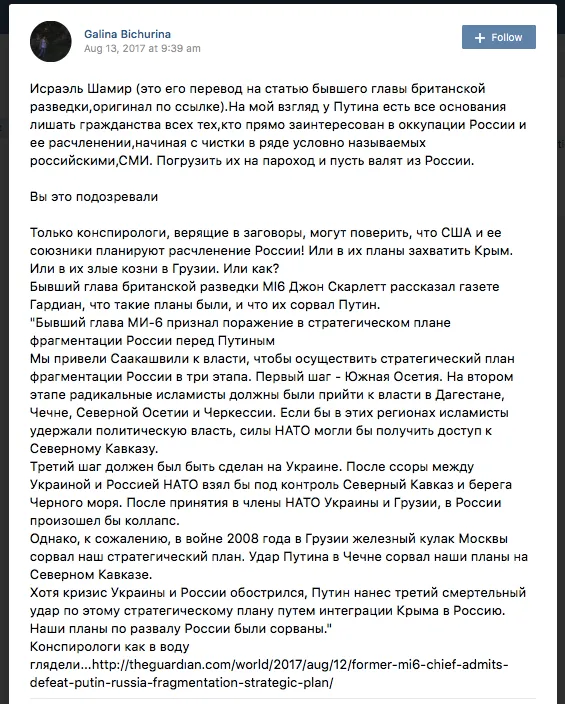

Yet a fourth variant of the story arose via a second Russian-language translation of the fake Guardian post — this one attributed to Israel Shamir, a controversial Russian-born commentator. Shamir had tweeted about the article early on August 13 under the headline, “You suspected it all along,” together with a fragment of text beginning, “Only conspiracy theorists could believe that the US and its allies…”

Вы это подозревали

Исраэль Шамир

Только конспирологи, верящие в заговоры, могут поверить, что США и ее союзники… https://t.co/ewvyOoos3a— Israel Shamir (@IsraelShamir) August 13, 2017

The tweet included a Facebook link, now defunct. However, the fragment of text was sufficient to locate a number of posts on the Russian social network VKontakte that reproduced the article, including this post from user Galina Bichurina, which, again, provides the link to the fake “Guardian” site.

None of these posts had massive pickup; even the REN TV article could only boast some 3,000 views and fewer than two dozen shares. However, the existence of at least four different translations of the story shows three things: the extent to which different Russian-language disinformation operators tried to push the story, the degree to which they were determined to do so despite its having been debunked, and the lack of coordination between them.

The Russian-language version of the fake story continued to spread because an active community had an interest in propagating the false narrative, despite the fact that it had already been debunked.

Different fakes, same pattern

The same kinds of patterns occur with the other fake news sites in this cluster. Another tweet posted by @alqazm_alarabi led to another apparently fake story mimicking The Guardian, this time with the apparent URL theguardia.com. The URL was shortened using bit.ly; however, a reconstruction of the address using GetLinkInfo.com reveals the full link as theguardia-dq2e.com, one of the fake domains exposed by BuzzFeed News.

The screenshot of the tweet, above, shows that the URL as shown on screen was completed with the character “ṇ” in order to make it look more like the word “guardian.” This is exactly the same principle as that used in the other fake story, for which the Turkish letter “ı” was used to flesh out the copycat URL.

This link is already broken, but, again, the tweet provided enough text for an effective Google search. This search led to a number of websites that reproduced the text, along with all of its many linguistic errors, starting with the headline, “US House of Representatives listed some Middle East’s terrorist parties.” The errors include sentences omitting the word “the,” such as: “Chairman Ed Royce formerly held meeting with Saudi Arabia’s Foreign Minister.” There are also garbled phrases, such as: “The House of Foreign Affairs Committee held a markup on Middle East and North Africa affairs.”

Other stories exposed in the BuzzFeed News article followed the same pattern of technical skill and linguistic incompetence. @DFRLab has located what appear to be the original, English-language texts of faked Haaretz and Atlantic reports; these were deleted from the fake sites where they originally appeared, but were reproduced by other sites.

The fake Haaretz story claimed that the family of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev had invested $600 million in Israel; it included linguistic oddities such as:

For example, few months ago, the spouse and son of the President of Azerbaijan bought a spectacular villa in Haifa worth $6 million. The security guard of Israel provides the safety of this place as the states of Azerbaijan requested.

The story purporting to come from The Atlantic claimed that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman had appointed his brother as foreign minister; it included the phrases “first in line to throne” and “He was formerly F-15 pilot and participated in the combat against ISIS.”

As with the other pieces described in this and in the BuzzFeed articles, the pages mimicking Haaretz and The Atlantic were quickly taken down. The linguistic errors alone were enough to expose the pieces as fakes.

Nevertheless, the fake Haaretz piece was defended by the Armenian outlet Armenpress, which, remarkably, wrote the following:

The examination of Armenpress reveals that there can be no talk about ‘fake’ news. In fact, the scandalous article has been published at Haaretz the evidence of which are the ‘screenshots’: the material is still in Google cache. Moreover, all the links in the maintained part of the website work correctly which also confirms that the news that created Baku’s counter reaction is nothing more than an article that has been posted on the website and later was hidden.

As with the REN TV article, this piece recasts the deletion of the story as a deliberate attempt to cover up a true article, rather than the deletion of a false one. It is unclear whether the authors realized that the article they were defending was based on a doppelgänger website; what is clear is the editorial eagerness to cover in depth a story apparently disadvantageous to Azerbaijan’s first family.

Conclusion

This cluster of doppelgänger websites provides a case study in the crafting of disinformation. The cluster’s geopolitical purpose, if any, is unclear, given the range of regions and subjects covered.

The fake sites all had features in common, beyond the technical links exposed by BuzzFeed’s reporters. They mimicked genuine websites by registering a domain name that was one letter short of the original, and then inserting a non-standard character to flesh it out. They reinforced the mimicry by copying the exact style of the original, and by linking back to genuine stories on the original.

Despite this technical skill, the fake stories on these copycat websites were crafted in an incompetent English that was quickly exposed as fake, and they failed to gain a significant audience. This suggests that they were either drafted in English by a non-native speaker — quite possibly a Russian-speaker — or else they were written in another language, and then translated into English.

The fact that so many of the articles were translated into (or back into) Russian on the pravosudija.net site, as shown by Silverman and Lytvynenko, raises the possibility that the main target audience was, in fact, a Russian-speaking one. (This would also explain the clumsiness of the English versions.) One of the key tactics of Kremlin propaganda is to quote, or to selectively misquote, foreign media sources in order to validate a chosen narrative. Where no such quotes exist, it would be a logical progression to decide to create them.

The final point is that these sites were rapidly exposed and deleted. Nevertheless, their content continued to spread, especially in Russian. Their spread was not viral, and remained, in English, on the fringes; however, the fact that this content had been debunked was not enough to stop its being shared by groups who were politically invested in it. This reinforces one of the main challenges of fake news: in order to boost a political agenda, users spread fake content even after it has already been exposed as fake.