UK Poisoning: Russia Recycles Responses

The Kremlin’s narrative on the Novichok poisoning sounds familiar

UK Poisoning: Russia Recycles Responses

The Kremlin’s narrative on the Novichok poisoning sounds familiar

The Russian government was quick to respond on Monday to the accusation that it was probably behind the poisoning of a former spy in England, using a rare military-grade nerve agent.

The response followed a pattern which @DFRLab has observed in other cases in which the Kremlin was accused of serious crimes. That pattern is the “4D” model of “dismiss, distort, distract, dismay.”

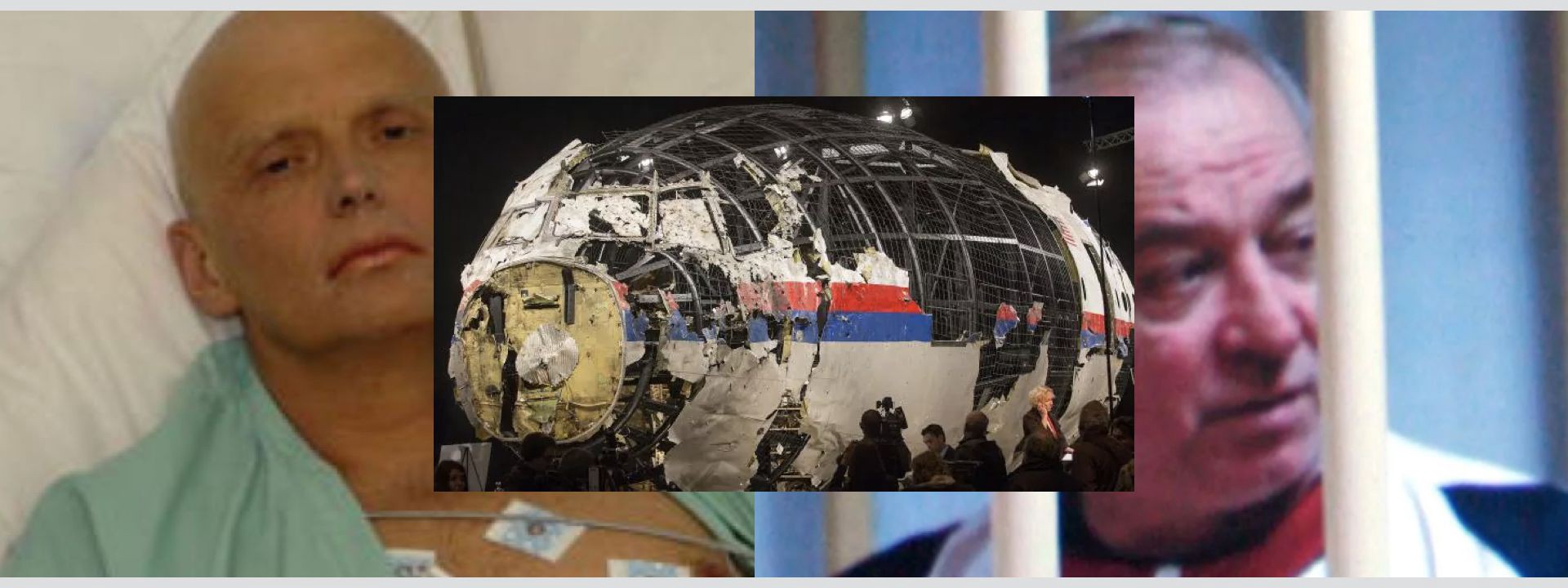

Judging by previous cases — especially the poisoning of former Russian agent Alexander Litvinenko in England in 2006 and the shooting down of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 over Ukraine in 2014 — we can expect to see more systematic use of the 4Ds by the Kremlin in the coming days and weeks.

The accusation

The case in question is that of Sergei Skripal, a former Russian spy living in England, who was found poisoned in the city of Salisbury on March 4, together with his 33-year-old daughter, Yulia.

After eight days of heated speculation as to how the Skripals were poisoned, British Prime Minister Theresa May set out the government’s preliminary findings in an address to the British parliament on March 12.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-vEMbRPb2lM

“It is now clear that Mr. Skripal and his daughter were poisoned with a military-grade nerve agent of a type developed by Russia.

This is part of a group of nerve agents known as ‘Novichok’.

Based on the positive identification of this chemical agent by world-leading experts at the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory at Porton Down; our knowledge that Russia has previously produced this agent and would still be capable of doing so; Russia’s record of conducting state-sponsored assassinations; and our assessment that Russia views some defectors as legitimate targets for assassinations; the Government has concluded that it is highly likely that Russia was responsible for the act against Sergei and Yulia Skripal.”

May’s exact understanding of whom to hold responsible became clear in the following paragraphs:

“Either this was a direct act by the Russian state against our country, or the Russian government lost control of this potentially catastrophically damaging nerve agent and allowed it to get into the hands of others.”

May then said that Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson had “requested” an explanation from the Russian government by the end of March 13. She added:

“Should there be no credible response, we will conclude that this action amounts to an unlawful use of force by the Russian State against the United Kingdom.”

May’s statement, while brief, did explain the foundation of the British government’s argument. It rested on the positive identification of the “Novichok” (Новичок, “Newcomer”) nerve agent by chemical warfare specialists; Russia’s history of producing the agent; and observation of the Russian government’s broader pattern of behavior.

Concerning that prior behavior, May laid especial emphasis on the murder of Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko, poisoned with radioactive polonium 210 in 2006. An inquiry into the murder, led by High Court judge Sir Robert Owen, found, in 2016, that Litvinenko was murdered by a former Russian agent, Andrey Lugovoi, with the “strong probability” that the murder was ordered by Russian intelligence.

The prime minister’s statement cannot be viewed as a full exposition of the evidence, but it did explain the foundation of the British government’s case, with by far the most important factor being the identification of the nerve agent itself.

Russia’s response

The Russian government’s response was swift. Within minutes of May’s statement, Russian news agency TASS reported a comment from Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova, who said:

“It’s a circus show in the British parliament. The conclusion is clear: another information and political campaign, based on provocation.”

Zakharova, who is famed for her trenchant replies, gave scant indication that the Russian government would respond to May in the manner which she may have hoped.

“Before making up more fairy tales, someone in the kingdom should tell us how the other (investigations) ended — Litvinenko, (former oligarch Boris) Berezovsky, (whistleblower Alexander) Perepilichny and many others, who died mysteriously on British soil. The Grimpen Mire is still holding onto its secrets.”

For reference, the Grimpen Mire is a dangerous marsh in the Sherlock Holmes novel, and Soviet film, The Hound of the Baskervilles.

Zakharova did not comment on the substance of May’s accusation.

Soon afterwards, Kremlin broadcaster RT quoted two Russian Senators as threatening reprisals for any British measures:

“The British must realize that they will face a very stiff response from Russia.” — Senator Igor Morozov

“If the UK decides to expel Russian diplomats in connection with the Skripal case, Moscow’s response will be adequate and swift, this situation as a whole looks like a well thought-out anti-Russian move.” — Senator Andrey Klimov

The Russian Embassy in London added its voice, issuing a statement that warned, “Current policy of the UK Government towards Russia is a very dangerous game played with the British public opinion, which not only sends the investigation upon an unhelpful political track but also bears the risk of more serious long-term consequences for our relations.”

The embassy also warned that “UK-based Russian journalists are receiving threats,” a warning carried as a standalone article by Sputnik.

Zakharova was the first to comment on May’s accusation, but by no means the first to comment on the broader case. The night before May made her announcement, Russian TV anchor Dmitry Kiselev, the head of the Rossiya Segodnya news agency, accused the UK of staging the attack on Skripal to “feed their Russophobia” and stage a boycott of the soccer world cup, to be held in Russia this summer.

"Deadly place": Russian state TV today surmises that Britain poisoned Sergei Skripal. "Only the British stand to benefit…to feed their Russophobia" & engineer "international boycott of World Cup." pic.twitter.com/Ya5A2Z40pB

— Steve Rosenberg (@BBCSteveR) March 11, 2018

The original video is online below (timestamp 1:56:00).

“Of course, they started howling at Russia at once. But if you think clearly, the only people who benefit from the former intelligence colonel’s poisoning are the British. Simply to feed their Russophobia. As a source, Skripal had already given everything, he wasn’t useful any more. But as a victim of poisoning, he was very useful…”

Even Kiselev was not the first to make this suggestion. On March 8, a commentator with the state news agency Sputnik, which belongs to the Rossiya Segodnya agency, suggested that the British government was behind the poisoning:

“The relentless Russophobia serves to condition the British public to be receptive towards more anti-Russian hostility. As we can see this week with the reckless innuendo against Moscow regarding the apparent poisoning of Sergei Skripal.

“Given their inveterate anti-Russian agenda, the British authorities have much more vested interest in seeing Skripal poisoned than the Kremlin ever would.”

The same article referred to the Litvinenko report — a 328-page document produced by a High Court judge — as a “dubious semi-official inquiry” that “presented no evidence” of Russian state involvement.

An RT article published on March 11 managed to avoid mentioning the Litvinenko report at all, instead claiming simply that “many public figures in the West accused the Russian government of alleged involvement” in his death.

These responses embody the Russian government’s four standard responses to criticism: dismiss the critic, distort the evidence (in this case, by challenging or omitting the Litvinenko inquiry), distract from the accusation by accusing the accuser of the same thing, and threaten reprisals.

Tactics of denial

These are all tactics which have been seen before. Zakharova’s description of the parliamentary procedure as a “circus show” is very similar to the Kremlin’s mocking response to the Litvinenko findings, as expressed by spokesman Dmitriy Peskov at the time. Peskov said:

“Maybe this is a joke. More likely it can be attributed to fine British humor.”

It also resembles Zakharova’s own response to the conclusion of the Joint Investigation Team (JIT) that the missile which downed MH17 was brought into Ukraine from Russia, and returned there after the disaster:

“Russia proposed working together and sticking to the facts. Instead, international investigators sidelined Moscow from full participation in the process, relegating our efforts to a minor role. It sounds like a bad joke, but they made Ukraine a full member of the JIT, giving it the opportunity to forge evidence and turn the case to its advantage.”

The claim by Senator Klimov that May’s accusation was a “well-thought-out anti-Russian move” echoes Zakaharova’s own response to the Litvinenko inquiry. She said:

“The Report of the Inquiry is a logical conclusion of a pseudo-legal play that was enacted by the UK courts and executive authorities with the sole purpose of slandering Russia and its leadership.”

It also echoes another Zakharova response to the JIT’s conclusions, this time the thesis that the conclusions had been “dreamt up” in advance, according to a political subtext:

“Arbitrarily assigning blame and dreaming up the desired results has become the norm for our Western colleagues.”

The accusation that Britain itself was behind the nerve agent attack, based on the theory of cui bono (“who benefits”), is essentially identical to one quoted by RT after the downing of MH17.

“The key question remains, of course, cui bono? Only the terminally brain dead believe shooting a passenger jet benefits the federalists in eastern Ukraine, not to mention the Kremlin. As for Kiev, they’d have the means, the motive and the window of opportunity to pull it off.”

Russian state outlets, indeed, aired a plethora of counter-theories after the MH17 crash, including that the aircraft had been shot down by a Ukrainian surface-to-air missile, a Ukrainian aircraft, an Israeli missile or the CIA. The Russian Ministry of Defense even published images purporting to show the Ukrainian weapons; these were later found to have been falsified, an extreme case of distortion.

The cui bono argument was headlined in an interview reported by Sputnik in October 2017, after a UN investigation found the Syrian government, Russia’s ally, guilty of a sarin attack on the village of Khan Sheikhoun in Syria which killed dozens, including many children.

“The first step in an investigation is to look at who would benefit from a crime. In this case, the evidence suggests that the Syrian government is absolutely the one that would not benefit. It’s the opposition that benefits.”

The accusation of Russophobia, made by both Kiselev and the opinion piece published by Sputnik, has been a standard Kremlin response to critics since the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, as @DFRLab has chronicled.

Even the senators’ warnings bear echoes of former responses. After the Litvinenko report was published, Peskov warned that it would be “capable of further poisoning the atmosphere of our bilateral ties.”

Conclusion

The Russia authorities’ initial response to May’s accusation follows a familiar pattern. Officials, politicians, and state media mocked the accusation, portrayed it as an anti-Russian and “Russophobe” plot, accused the United Kingdom of committing the crime, and warned of potentially serious consequences.

This is the same pattern which has been observed in other critical moments, especially the Litvinenko murder and the downing of MH17.

On the basis of this initial response, it appears highly unlikely that the Russian government will provide their British counterparts with the explanation May demanded — especially given that Russian is to hold presidential elections on Sunday. Rather, the response so far embodies a contrary narrative in which Russia is seen as the victim, the West is the aggressor, and the foundation of evidence is left unaddressed.

That response, and the 4D techniques which constitute it, can be expected to continue, and intensify, in the coming days.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.