#PutinAtWar: Russia’s Troll Diplomacy

Russian embassies mock Britain’s response to poisoning

#PutinAtWar: Russia’s Troll Diplomacy

Russian embassies mock Britain’s response to poisoning

Late on March 12, the Russian Foreign Ministry’s official Twitter feeds began mocking the British government with tweets accusing the British of blaming Russia for everything, even the weather.

The posts followed an accusation by UK Prime Minister Theresa May on March 12 that Russia was “highly likely” to be behind the poisoning of former spy Sergei Skripal, his daughter, and a number of UK bystanders, using a powerful nerve agent from the Novichok family.

The Ministry’s Russian-language feed, @mid_rf, was the first to post a video showing snow in Britain, together with the awkward caption “#HighlyLikelyRussia casted snow on Britain” and the equally awkward Cyrillic transliteration, “ХайлиЛайклиРаша.”

Искренние слова благодарности г-же Мэй за #HighlyLikelyRussia

Ушло в народ 🌬

А вот и первая новость для «ХайлиЛайклиРаша»⬇ pic.twitter.com/wBVMhUYQos— МИД России 🇷🇺 (@MID_RF) March 12, 2018

Half an hour later, the Ministry’s English-language feed followed suit.

Sincere thanks to Mrs May for #HighlyLikelyRussia

It's gone to people 🌬 And here is the first news for #HighlyLikelyRussia ⬇ pic.twitter.com/sy3qMzBitU— MFA Russia 🇷🇺 (@mfa_russia) March 12, 2018

The two posts continued a pattern of defensive comments from Russian officials and media, which, as @DFRLab has already reported, follow the pattern of “dismiss, distort, distract, dismay.”

The mocking tone matched the comment by Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova that Prime Minister May’s statement to the UK Parliament was a “circus show,” and the claim by state television anchor Dmitry Kiselev that the British accusation was done “simply to feed their Russophobia.”

"Deadly place": Russian state TV today surmises that Britain poisoned Sergei Skripal. "Only the British stand to benefit…to feed their Russophobia" & engineer "international boycott of World Cup." pic.twitter.com/Ya5A2Z40pB

— Steve Rosenberg (@BBCSteveR) March 11, 2018

The intention seems to have been to create a viral hashtag, but by 13:30 UTC on March 13—some fourteen hours after the initial English-language post — the hashtag had only generated under 1,000 tweets.

By that point, the Foreign Ministry’s Russian-language feed, which has 1.23 million followers, registered just 109 retweets of its post. The English-language feed, with 174,000 followers, had 122 retweets, although the video was marked as scoring almost 35,000 views.

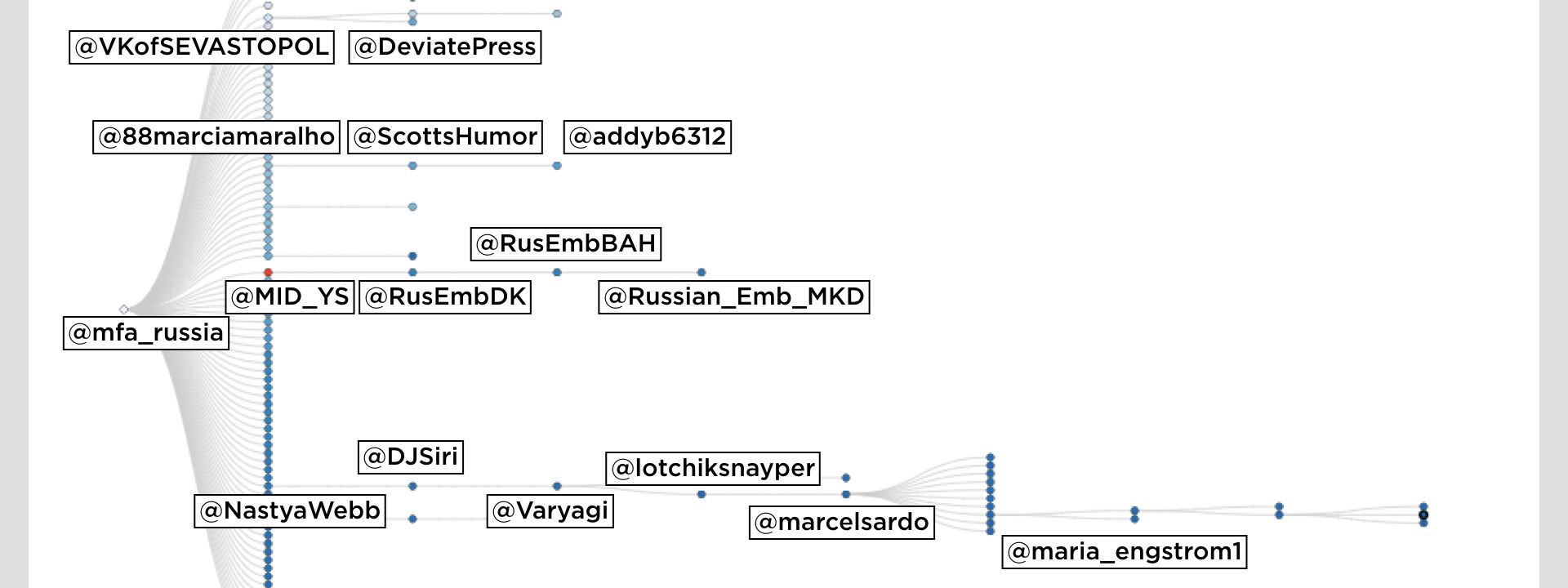

According to a network scan conducted with online tool Sysomos, the English-language tweet did not spread far beyond the Ministry’s own followers. Of the accounts which retweeted it, only a few were retweeted in turn. Only in one cluster did the tweet go through more than four retweets, an amplification process which can create virality if performed over enough revolutions.

The amplification community in this case was largely dominated by known, and explicit, Kremlin supporters. The most notable is @marcelsardo, self-described as a “pro-Russia media sniper;” @Varyagi is an outspokenly pro-Kremlin troll account; @maria_engstrom1 regularly shares pro-Kremlin talking points on issues including the White Helmets rescue group in Syria, the shooting down of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 over Ukraine, and the concept of “Novorossiya,” formerly a self-proclaimed term for eastern Ukraine.

#Lavrov dealing with #Britain's latest baseless braindead accusations against #Russia in a professional manner. The amount of lies Theresa May regurgitated this time is simply staggering. Will she choke on them? Stay tuned. pic.twitter.com/6oQLG8bI0A

— Varyagi Z ☦ 🇷🇺 (@varyagi) March 13, 2018

@MID_YS, meanwhile, was the foreign ministry’s local branch in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk in Russia’s far east. @RusEmbDK, @RusEmbBAH and Russian_Emb_MKD are Russian embassies in Denmark, Bahrain and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, respectively.

Thus, while the ministry’s tweet did spread through this community, it was very much a case of preaching to the converted: those who passed it on to one another were accounts which already support the Kremlin vocally.

It was instructive to compare the spread with the Russian-language post. This was similar in scale, but spread more evenly through a number of sub-communities, as the following scan indicates:

Again, however, this included a number of official accounts, like the Russian Embassy in Denmark, the Russian Mission to the United Nations in Geneva (@mission_russian), and foreign ministry accounts in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk (@MID_YS) and Samara (@MID_SAMARA). It also included @Varyagi and @VKofSevastopol.

A number of other Russian diplomatic missions launched their own undiplomatic posts. The Russian Embassy in London, for example, commented on a report that the UK’s telecommunications regulator, Ofcom, may be preparing to terminate the license of Kremlin broadcaster RT.

Truth is the first casualty pic.twitter.com/gyUuMK9xEb

— Russian Embassy, UK (@RussianEmbassy) March 13, 2018

“Truth is the first casualty,” the embassy posted, failing to mention that RT is, by its own chief editor’s admission, the “information weapon” of the Russian government.

This tweet achieved a little more audience penetration, with 275 retweets registered by 1900 UTC on March 13. It also stretched further, amplified through multiple stages and communities, as the graph below indicated.

One of the Embassy’s first amplifiers was the Russian Embassy in Canada (@RusEmbassyC). Another early mover was commentator Max Keiser (@MaxKeiser), who hosts his own show on RT. Somewhat later, the tweet was amplified by Mark Sleboda (@MarkSleboda1), another RT pundit, and an account called @Navsteva, which promotes pro-Kremlin narratives on issues such as the shooting down of Malysian Airlines flight MH17, the Russian annexation of Crimea, and Bana Alabed, a seven-year-old girl who tweeted from Aleppo during the siege of the city in 2016.

Other amplifiers belong to a community of fringe, and often conspiratorial sites. These included the “Off-Guardian” (@OffGuardian0), whose motto is “Publishing the facts and opinions the Guardian tries to ignore,” and website RenegadeInc.com, whose top story on March 13 was a defense of RT against the “British political class and neoliberal media.”

Again, therefore, the Embassy’s defense of RT appeared to have been largely confined to existing fans, and employees, of RT.

A final embassy notorious for troll content, the Russian Embassy in South Africa, also joined the campaign, this time posting a meme including the theme music of slapstick British comedian Benny Hill.

So… out of the blue #Russia "decides" to eliminate ex-Russian intelligence traitor officer turned British spy, ahead of Russian Presidential election & the #WorldCup, uses easily traceable nerve agent (!) supposedly produced in Russia… Really? Only one comment: Cui prodest? pic.twitter.com/ulA0Iz133d

— Russian Embassy in South Africa 🇷🇺 (@EmbassyofRussia) March 12, 2018

This tweet enjoyed the greatest success of any official troll post, counting almost 600 retweets by 20:00 UTC on March 13. It repeated the “who benefits” argument already aired repeatedly by Kremlin outlets to imply British guilt.

The tweet passed through so many rounds of retweeting that it would be impractical to annotate and reproduce the entire scan. However, the key amplifiers are visible on this chart:

This was a particularly interesting study. The initial impact was largely from the embassy itself: few of its direct retweeters achieved any further spread. Two accounts stand out: @MauriceSchleepe, a vocally pro-Kremlin account, and @maria_engstrom1, which also amplified the Foreign Ministry’s posts.

These accounts were important, not for their own impact, but as links to further amplifiers. One, @OffGuardian0, also amplified the London embassy. Two others, @VanessaBeeley and @PartisanGirl, are pro-Kremlin and pro-Syrian regime activists who feature regularly in Russian attacks on the White Helmets, a Syrian civilian search and rescue aid group. A fourth, @GrahamWP_UK, is Graham Phillips, a British supporter of the Russian-led separatists in Ukraine. A fifth is the account @TeamTrumpRussia, which currently posts pro-Kremlin content, but in 2016 largely posted attacks on Hillary Clinton.

These amplifiers gave the tweet a substantial new lease of life. However, again, they all belong in the ideological core of Russian government backers; thus, the Russian Embassy of South Africa’s post was best viewed as reaching more Kremlin supporters, but not necessarily more unconvinced users.

Conclusion

The Russian diplomatic missions’ comments largely fell on familiar ears. Their spread was limited in number, and confined to existing support groups.

Their public impact was therefore extremely limited. These posts largely appeared to be attempts to antagonize the British government, and to appeal to the conspiratorial fringe of English-language media.

These posts were interesting for the light they shed on the close cooperation between embassies, RT commentators and independent trolls. In each case, messages that were launched by official accounts owed their main amplification to a small group of users, some of them RT associates, others known pro-Kremlin activists. This was a worldwide effort, involving embassies and supporters in both Europe and North America.

It also underlined the Kremlin’s entrenched attitude to Britain’s threats. Such tweets are a means of rhetorical escalation, not of reconciliation; and they came from embassies, and the Russian Foreign Ministry itself. Further escalation is highly likely.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.