#TrollTracker: Kremlin Supporters Strike Back

Pro-Kremlin Twitter users dismiss, distort, distract, and dismay

#TrollTracker: Kremlin Supporters Strike Back

Pro-Kremlin Twitter users dismiss, distort, distract, and dismay

On March 24, @DFRLab reported how pro-Kremlin Twitter users had amplified a Twitter poll based in the United Kingdom, which questioned the British government’s trustworthiness in the aftermath of the poisoning of former spy Sergei Skripal, in an apparent attempt to influence the vote.

Those Twitter users, and others like them, were quick to attack the report, targeting @DFRLab and those who reported on pro-Kremlin trolling with insults, criticisms, and threats.

Such trolling is an inseparable part of life for those who report on pro-Kremlin disinformation. The current case, however, illustrated the techniques frequently used in such attacks, which can be described as “dismiss, distort, distract, dismay.”

Dismiss

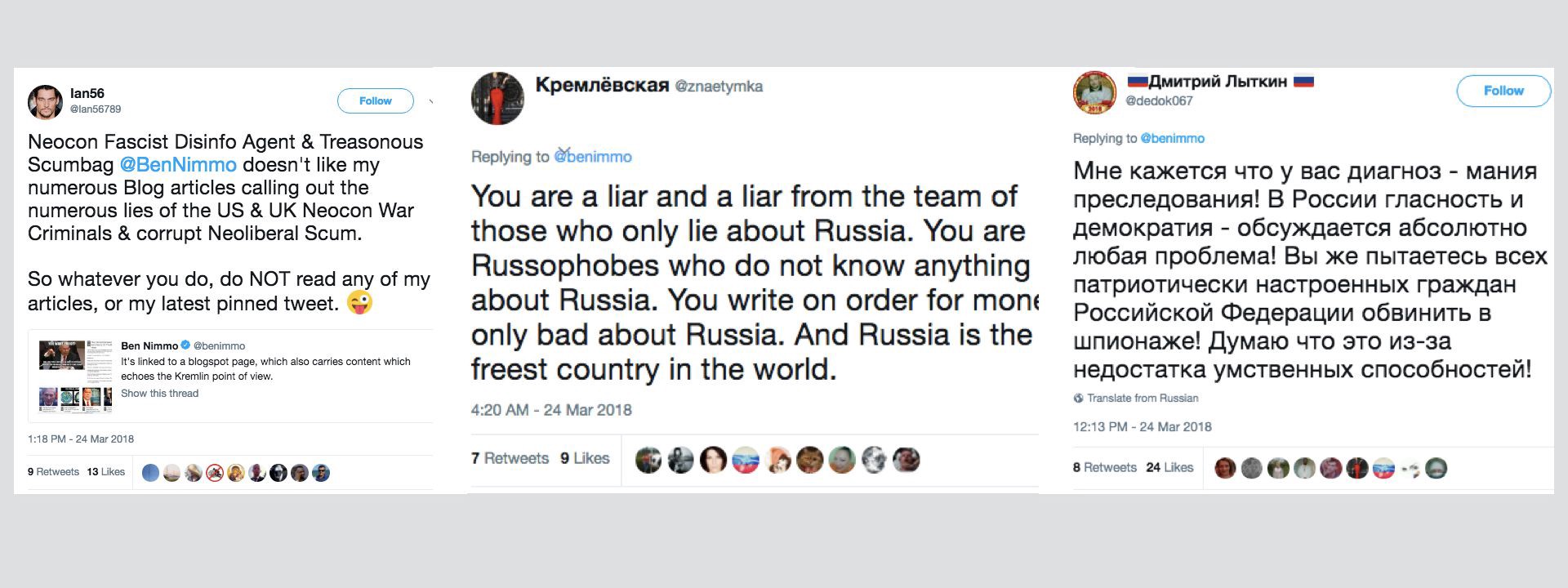

The simplest method of trolling researchers is to insult them, and thus to dismiss their work without looking at the evidence they adduce. Some of the attacks which followed the publication of our research attacked @DFRLab and other researchers, notably the Bellingcat group of investigative journalists. Here, the main claim was that such groups are “neocons.”

Rather more attacks were personal. They were distinguished from evidence-based criticism or principled disagreement, both of which are an integral part of debate, by their pejorative tone, and their focus on the author, rather than the theme. It is this which qualifies them as trolling, rather than discussion.

The attacks were more noteworthy for their invective than their accuracy of fact or language. For example, @Ian56789 used the handles @BenNimmo and @Ben_Nimmo instead of the correct @Benimmo, while @Syricide incorrectly attributed the report to the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), rather than @DFRLab.

@znaetymka used the pejorative “Russophobe,” an adjective which the Russian government regularly uses to dismiss its critics.

Dismissal is the simplest form of trolling, as, by definition, it avoids analyzing the evidence. These attempts fit firmly in that context.

Distort

The distortion technique requires more attention to detail, both in the creation and the rebutting. It is therefore a rarer technique.

On this occasion, it was chiefly deployed by @ValLisitsa, an account attributed to Ukrainian-born pianist Valentina Lisitsa. This account was a significant amplifier of the original online poll, and its retweet was picked up by a number of Russian-language accounts.

As we wrote at the time:

None of these Russian accounts has an organic focus on, or interest in, UK politics; their content is dominated by pro-Kremlin messaging, mostly in Russian or English. Their purpose in retweeting the poll therefore seems to have been to spread it to a Russian audience which could be expected to vote against the UK government.

On March 24, Lisitsa responded, arguing that her retweet was posted after the Twitter poll closed, and that it could not, therefore, have influenced the vote. She accompanied the post with a screenshot of a tweet which quoted the original poll and praised “ordinary Britons” for not “losing their common sense despite the hysteria spread by politicians and the media.”

Lisitsa’s response was deceptive. The original poll, from an account called @Rachael_Swindon, was posted at 4:56 p.m., UK time, on March 17.

According to a subsequent post from the same author to British Prime Minister Theresa May, the poll was set to run for 24 hours.

The tweet to which Lisitsa referred was posted at 7:12 p.m. on March 18. This was, indeed, after the expiry of the poll.

However, Lisitsa was referring to the wrong post. Our article and scan actually referred to a separate retweet of the poll — not a quote — which she had posted that morning. A screenshot of her timeline for March 17–18 showed that this retweet was posted immediately before a Russian-language post sharing an AFP article on Syria.

The post quoting the AFP story was placed online at 7:53 a.m. on March 18. The retweet of the @Rachael_Swindon poll must, therefore, have been posted before then. As such, it falls well within the poll’s 24-hour expiry limit. Lisitsa’s defense distorted the facts by referring to the wrong post and omitting the right one.

Other attacks distorted the details of @DFRLab’s reporting. Lisitsa accused @DFRLab of calling her both a “paid troll” and a “Russian bot.” In fact, our post did not apply either term to her, describing her account thus:

This appears to be the account of concert pianist Valentina Lisitsa, an ethnic Russian born in Ukraine, who was dropped by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in 2015 for comments on the Ukrainian conflict deemed to have been ‘deeply offensive.’

Lisitsa initially also complained at the use of the term “ethnic Russian born in Ukraine;” in a later post, she called herself “Ukrainian-American,” but took the Russian reference as a compliment. Curiously, Lisitsa’s incorrect claim of being called a “bot” was picked up by U.S. commentator Max Blumenthal, who used it as the basis for two angry tweets.

It was unclear whether Blumenthal knowingly distorted the evidence, or simply took Lisista’s incorrect claim at face value, without verifying the facts.

Distortion efforts often focus on twisting the original argument, to make it easier to refute. Another account, @temporalsin, distorted our findings, which were that Russian-language and pro-Kremlin accounts appeared to have influenced the original poll without its creator’s awareness.

This appears to be distortion for the sake of mockery, thus combining the dismiss and distort techniques.

Finally, @Malinka1102 took a different approach again, commenting that, thanks to @DFRLab, the account had gained “quite a few” new followers.

According to two archive snapshots taken on March 23 and March 26, before and after the @DFRLab posts, @Malinka1102’s following increased from 4,659 to 4,680, a growth of 21 followers, or 0.45 percent, over three days. Whether this counts as “quite a few” new followers is open to doubt; it may be another attempt at mockery by distortion.

Distract

The third troll technique is to distract from the subject by accusing their critics of other misdemeanors. In this case, many Russian-language accounts leveled accusations of being “propaganda” (a word which did not feature in the original report) and “troll.”

English-language posts made similar claims.

Such posts appeared to be an attempt to distract attention from the original point, which was the apparent attempt by pro-Kremlin and Russian accounts to distort an originally UK-based poll.

Dismay

The final troll tactic is dismay: targeting a perceived opponent with threats or warnings, no matter how implausible.

The account @Enchanteressse, for example, which we identified in the original post as amplifying a retweet by @malinka1102, threatened legal action.

Another Russian-language account, @MarKizZ17, promised a less legal retaliation: death by the Novichok nerve agent. Another user replied to suggest a long-range Kalibr missile.

Even more graphically, though with a flattering assessment of @DFRLab’s importance, @KupranSergo threatened to give the author a royal execution.

None of these specific threats appears particularly credible. We include them here as concrete illustrations of the verbal aggression which forms a part of the troll’s arsenal, and which usually seems meant as a dismaying tactic.

…And Silence

One further response deserves a mention. The euphoniously-named @_FUCKTHEUSA called on Twitter users who had been identified in our earlier post to report it as a terms-of-service violation, together with a screenshot suggesting that @_FUCKTHEUSA was also doing so.

This procedure, when carried out on a large scale, is known as “brigading,” and is designed to have critics taken offline temporarily or permanently. As of March 26, however, it had had no discernible impact, and the tweet had not been retweeted.

Conclusion

The response to @DFRLab’s post provides a useful sample of the range of tactics which can be used to shout down critics without engaging with the content of the criticism.

Many posts attempted to dismiss @DFRLab’s findings. Some distorted either the facts, or @DFRLab’s reporting of them. Some posts attempted to distract attention from the initial article, while a few issued more or less violent threats, in an apparent dismaying tactic.

These techniques are not new. It is, however, less common to find all of them deployed at the same time. The response to the @DFRLab post is thus a case study in the range of responses which can be deployed.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.