#TrollTracker: Disinformation Surge from Skripal to Syria

Assessing Western claims of a spike in Syria-related disinformation

#TrollTracker: Disinformation Surge from Skripal to Syria

Assessing Western claims of a spike in Syria-related disinformation

On April 14, the Pentagon claimed that the “Russian disinformation campaign” over the recent Western missile strikes in Syria had already begun. On April 16, British media reported a twenty-fold increase in “disinformation” related to the strikes.

@DFRLab has already assessed another of the Pentagon’s claims — a “2000% increase in Russian trolls” over a 24-hour period — and found it unsupported by the evidence. In this post, we assess the broader topic of a surge in disinformation around the chemical attack and missile strikes in Syria.

There is considerably more evidence to support this claim, as a series of social media scans using online aggregation tools demonstrate.

“False flag” narrative

One of the central arguments of those who oppose the Western version events is that the chemical attack launched against civilians in Douma, Syria, on April 7 was a “false flag” strike. We would consider this a flawed argument, for three reasons.

- The “false flag” claims began as soon as the attack was reported, and well before any evidence could have been analyzed, suggesting that their intention was to pre-empt any findings rather than comment on them.

- The accounts which launched the claims made identical arguments about the Khan Sheikhoun sarin attack of April 2017, which a United Nations probe subsequently found to have been committed by Syrian government forces. Some made the same claim over other incidents involving Russian or Syrian forces which have since been verified.

- The “evidence” put forward rested primarily on an analysis of the characters of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and the White Helmets rescue group, rather than the broader evidence of events.

Accounts which advanced these claims while believing them to be false would be committing disinformation.

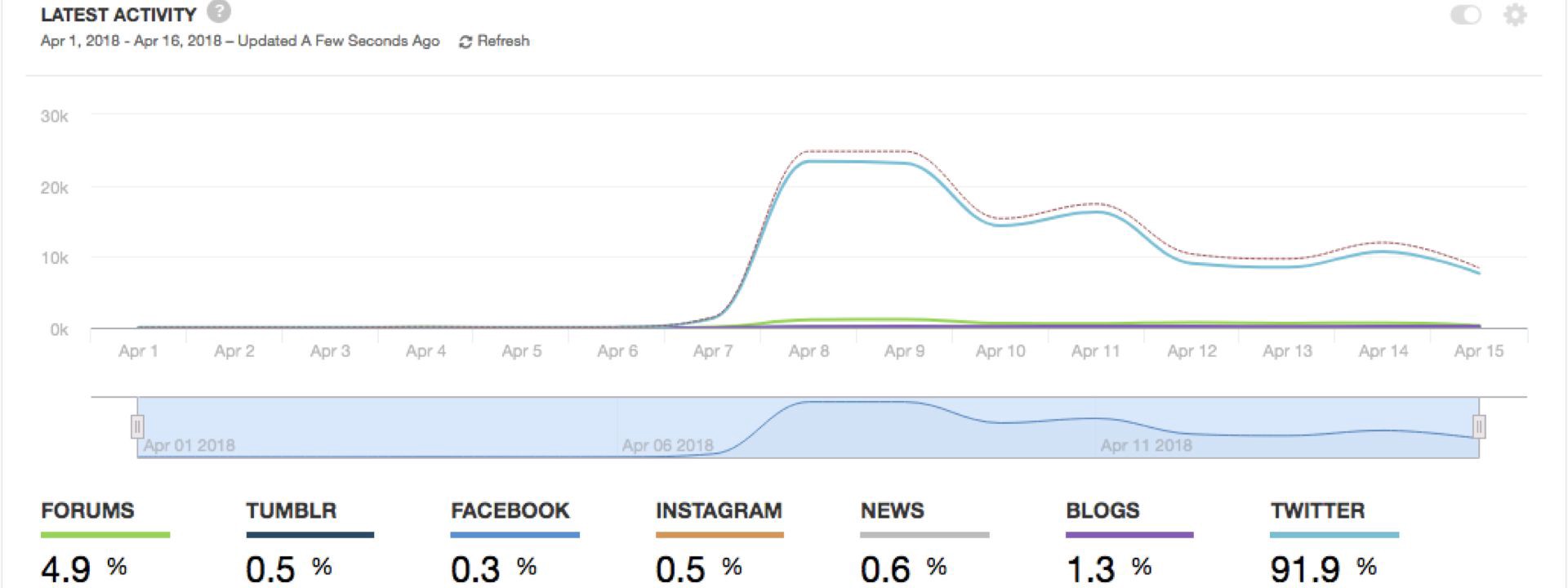

A scan of the terms “Syria” and “false flag” or #falseflag using the Sysomos online tool showed a surge in uses of the term beginning on April 8. Posts using the term continued at a high, but diminishing, level throughout the week that followed.

The increase in traffic from all sources on these phrases went from 1,500 mentions a day on April 7 to 24,800 mentions a day on April 8. This is approximately a seventeen-fold increase. If measured from April 6 to April 8, the increase is 194-fold (from 128 posts to 24,800). The claim of a twenty-fold increase thus appears to be in line with such traffic, with the precise figure depending on exactly which baseline is taken.

Not all these posts were of Russian origin. As @DFRLab has already written, the “false flag” theory was driven by representatives of diverse groups — primarily pro-Kremlin accounts, primarily pro-Assad accounts, and far-right or conspiratorially-minded accounts in the United States and Europe.

Thus, it is accurate to speak of a major increase in online activity promoting this narrative about the Syria chemical attack and subsequent strikes; the nuance lies in the sources. Care is therefore needed in labeling such incidents, to avoid unintended confusion.

“Who benefits?”

One of the main arguments put forward by defenders of the Syrian regime was that it would have been illogical for Assad or his forces to launch the chemical attack, because they were already winning.

This argument is flawed: many users made the same argument after the sarin chemical attack on Khan Sheikhoun in April 2017. In that case, as we have noted, a UN investigation found that Assad’s forces had indeed launched the strike — indicating that the Syrian leader’s calculations are based on a different set of considerations than those of his supporters.

However, it provided a useful second reference to gauge the level of activity around claims attributing the 2018 attack to Assad’s opponents. For a unique search term, the argument is encapsulated in the term “cui bono?”, Latin for “to whose benefit?”, the use of which soared after April 7.

Overall traffic on this phrase was lower, at 4,600 mentions; it is, after all, a somewhat niche phrase. The context was primarily related to Syria, as this word cloud makes clear.

Traffic on this phrase was mixed. Some posts came from journalists disputing the “cui bono” argument. Others came from pro-Kremlin, pro-Assad, and far-right users, confirming the narrative alignment between them.

Again, the numbers show that claims of a spike in activity on the “cui bono” argument are justified, but that great care should be taken in identifying the affiliation of the different users and their likely prime motivations.

The White Helmets

A third narrative element which surged over the same period was the claim that the White Helmets rescue group, who provided much of the initial evidence of the chemical attack, are an offshoot of Al Qaeda.

This is a longstanding disinformation narrative which has been promoted systematically by pro-Kremlin and pro-Assad users since the siege of Aleppo in late 2016, when the White Helmets emerged as one of the main sources of evidence for apparent war crimes committed by the Syrian and Russian forces.

According to a scan for the terms “White Helmets” and “Qaeda” from April 1 to April 16, traffic climbed after the April 7 attack, then surged from April 13 to April 14, with total traffic approaching 7,300 posts.

This traffic was strongly negative, with posts claiming that the attack was a false flag, a hoax or a psychological operation (psyop) launched to trigger Western intervention, as this scan of hashtags shows.

Yet again, the most retweeted posts came from users of varying affiliations, as this scan shows; curiously, half of the top tweets in this scan, including a post by U.S. libertarian Ron Paul, were made well before the scan began, indicating that other users chose to retweet them after the Syrian chemical attack — presumably as validation of the narrative.

The Skripal case

One other factor is worth mentioning here, and that is the regularity with which the “false flag” and “cui bono” arguments have been put forward to defend the Russian government’s position on other incidents. As the “cui bono” word cloud cited above indicates, traffic did not just mention Syria in April: it also mentioned former Russian spy Sergei Skripal, found poisoned in the English city of Salisbury on March 4, 2018.

Online behavior on the Skripal case was strikingly similar to that on the Syrian attack. Traffic on the terms “false flag” and “Salisbury” climbed steeply on March 13, albeit on a smaller scale, after British Prime Minister Theresa May told the British parliament that Skripal had been poisoned with the “Novichok” nerve agent.

Again, pro-Kremlin and far-right users combined to amplify the “false flag” narrative, and were among the most-retweeted users.

The speed with which the “false flag” narrative shifted from Salisbury to Syria was exemplified by these posts from @Ian56789, a pro-Kremlin account which we consider likely to be a influence account run by a Russian troll farm, and which switched from one claim to the next within a few hours on April 8.

The same user also called the April 2017 sarin attack, and the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 over Ukraine in 2014, “false flag” attacks. As we have mentioned, a UN investigation found Assad’s forces responsible for the sarin attack; an international criminal probe found that the launcher which downed MH17 entered Ukraine from Russia and returned there after the disaster. “False flag” therefore appears to be this account’s standard response to incidents which cast Russia and its allies in a poor light.

Conclusion

A number of factors emerge from these scans. First, the claim of a twenty-fold increase in traffic on anti-Western narratives of low credibility, as exemplified by the “false flag,” “cui bono” and “White Helmets / Al Qaeda” narratives, appears justified.

The exact scale of the increase depends primarily on the baseline used, but it is certainly not a material distortion to speak of a twenty-fold increase — although in such cases, identifying the baseline and terms of reference would be an important addition.

Second, however, the attribution of this activity is complex, and touches multiple groups. The same narratives were shared by pro-Kremlin, pro-Assad, far-right and conspiracy-minded users, as well as some more mainstream ones. While the main arguments have been heavily promoted by Kremlin channels, and in the case of the Salisbury poisoning originated there, it would be over-simplifying the case to term all this purely “Russian” in origin.

This leads to a larger point, which is the importance of evidence-based research, and of precise terminology. Not all activity which is beneficial to the Kremlin originates from the Kremlin, just as not all users who support Russian government narratives are paid Kremlin trolls.

Disinformation thrives in environments in which information is not clearly presented and leaves room for misunderstanding, whether accidental or deliberate. Reducing the potential for such misunderstandings is a vital part of narrowing the gap in which disinformation actors can operate.

Update: On April 20, 2018, the user behind Twitter account @Ian56789 was named in a blog post on its own site, and interviewed by Sky News. @Ian56789 therefore appears to be a pro-Kremlin account, rather than one directly run by a Kremlin operation.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.