#TrollTracker: From Tags To Trolling

How tweets to a small group precede attacks on critics of the Syrian and Russian regimes

#TrollTracker: From Tags To Trolling

How tweets to a small group precede attacks on critics of the Syrian and Russian regimes

A small group of Twitter users appears to have been conducting a campaign of targeted harassment against critics of the Syrian and Russian regimes for at least eighteen months.

Their apparent targets have included journalists, civil society, and open-source researchers. Some of their initial posts, though by no means all, have been followed by sustained online attacks on those targets.

Their method is relatively crude, using public posts to summon attacks. The core group is small: approximately fifty accounts. Nevertheless, some of its attacks have been so effective that they have drowned out other voices, dominating the conversation around the targets’ usernames with hostile tweets.

This post assesses how the group operates by analyzing some of its activities. This is only a sample: more have been attempted. It is important to recognize the methodology, as a first step in understanding the mechanics of online harassment.

Summoning The Group

On April 20, 2018, Guardian political editor Heather Stewart’s Twitter timeline suddenly showed a surge in activity. Mentions of her handle soared tenfold over the previous day, with the majority of posts bitterly hostile.

Part of the traffic was organic, driven by user reactions to an article on Russian disinformation, which she had just published. But analysis by @DFRLab shows that part was orchestrated, and generated by a small group of coordinated users.

The incident began overnight on April 19–20, when Stewart published an article headlined “Russia spread fake news via Twitter bots after Salisbury poisoning — analysis,” and promoted it with a tweet.

The article reported a British government claim that Russia had used online trolls and bots to generate a 4,000 percent increase in propaganda since the poisoning of former spy Sergei Skripal on March 4, 2018. The original version, archived here, and based on the government’s analysis, named two Twitter handles as “bots”: @Partisangirl and @Ian56789.

This was a misidentification. As @DFRLab has written (for example here, here and here), @Partisangirl is a prominent pro-Syrian regime activist, while @Ian56879 is a pro-Kremlin user, although not, as we originally suspected, run by a Kremlin influence operation. The Guardian article has since been corrected accordingly.

The two named accounts were quick to respond in their signature styles. @Partisangirl called Stewart a “lemming” and a “robot,” while @Ian56789 demanded a public apology. Mentions of their handles dominated the traffic around Stewart’s account from April 18–23, as this word cloud confirms:

These reactions were hostile, and were heavily amplified by the two accounts’ followers. However, there is no evidence to suggest that this was a case of targeted harassment.

The Troll Whistlers

By contrast, the traffic which followed on the morning of April 20 appears to have been coordinated among a small group of users, with the apparent purpose of generating online attacks against Stewart.

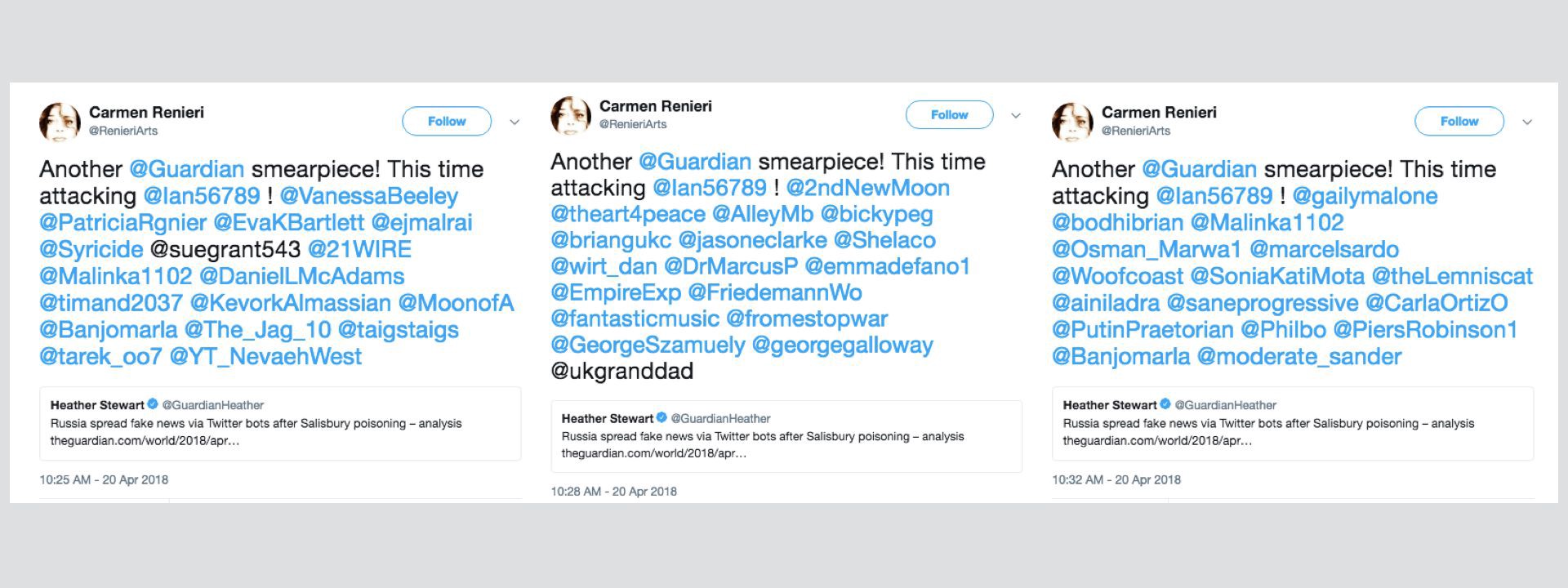

Starting at 10:25am, UK time, an account called @RenieriArts, screen name “Carmen Renieri,” posted three tweets in quick succession.

Each post quoted Stewart’s initial tweet, called her article “another @Guardian smearpiece,” and tagged many other users — most of them vocal supporters of the Russian and Syrian regimes.

Tagging other users is, of course, a regular practice on Twitter. It serves to draw their attention to particular posts, usually as a way of asking for amplification or endorsement. However, it is unlikely that Renieri wanted to amplify Stewart’s post, given her criticism of it.

Rather, this appears to be an attempt to draw a large number of other users’ attention, not just to Stewart’s article, but to her tweet.

The immediate sequel to the three Renieri tweets was a series of abusive tweets sent to Stewart’s timeline by some of the accounts which Renieri had tagged.

Fifteen minutes after Renieri tagged it, for example, the account @Banjomarla posted a reply directly to Stewart’s tweet:

This reply was personal, rather than critical: it accused Stewart of being “lame,” and called her report “the cheapest trick in town.” It was retweeted by Renieri and other accounts which she had tagged, including @wirt_dan and @The_Jag_10.

Other insults followed from other accounts which Renieri tagged. @Bickypeg, tagged at 10:28am, replied to Stewart at 10:51am, calling the Guardian “the thinking man’s Sun,” in reference to one of Britain’s tabloids. Soon after, @JasoneClarke replied to Renieri, but tagged Stewart, saying that he was ashamed of the latter; Renieri, @wirt_dan and @GeorgeSzamuely, another of the accounts tagged by Renieri, retweeted it.

The posts continued into the afternoon. At 11:27am, @malinka1102 quoted Stewart’s original tweet, calling it “fake news.” She then replied to Renieri’s original post, saying, “Just commented on @guardian @GuardianHeather #fakenews BS.” Renieri replied to confirm that she had retweeted the @malinka1102 post.

This exchange suggests both a degree of coordination, and that Renieri’s intent in tagging the group was to invite hostile comments against Stewart.

That was certainly the effect. By just after 2:30pm, @FriedemannWo, @AlleyMb (twice), @DanielLMcAdams, and @EvaKBartlett had all joined the conversation, either quoting or replying to Stewart’s original tweet in pejorative terms. Together, the tweets from @RenieriArts and those whom she tagged generated some 350 retweets and comments — roughly one fifth of all mentions of Stewart during that period.

An automatically generated word cloud for posts from 8:00am to 3:00pm that day shows that Renieri gained enough mentions to show up as a distinct, albeit minor, theme. Given that most of the attacks on Stewart from the tagged group did not mention Renieri, this suggests that the group had a significant impact on the conversation.

The vocabulary used was only mildly abusive, using pejoratives including “crap,” “BS,” and “neocon Guardian rag.” Individually, none of these posts would qualify as especially intimidating. However, the coordinated nature of the efforts would have resulted in a large number of angry and insulting posts appearing in Stewart’s personal notifications, without the underlying coordination mechanism being apparent.

As such, Renieri’s tweets served to draw the other users’ attention, and insults, to Stewart’s post. This is similar to the practice known as “raiding,” in which users alert one another to online posts or communities in order to overwhelm the target with negative or controversial comments.

A Long History

The group which Renieri tagged has been active for a long while: as early as September 2016, she tagged many of them while retweeting posts from the BBC’s Panorama program to two journalists, promoting a documentary on the siege of Aleppo.

The first was Julian Roepcke of BILD Zeitung; the second was investigative journalist (and now Atlantic Council Senior Fellow) Eliot Higgins. Both have written extensively on open-source evidence of potential war crimes in Ukraine and Syria, and been attacked by supporters of the Russian and Syrian regimes as a result.

Strikingly, the second of Renieri’s posts did not contain any authored comment, only a quote from Panorama to Higgins, and the account tags. It would be implausible to suggest that Renieri tagged the other accounts because she wanted them to amplify Panorama’s post: again, this looks like an attempt to draw their attention to it.

A few of the members reacted. Users @malinka1102 and @marcelsardo added mocking replies to Renieri’s first post. Both tagged @BBCPanorama (and would therefore have been visible in its timeline); @malinka1102 also tagged Roepcke.

@Syricide quoted a BBC Panorama post about the documentary directly, calling the BBC “infamous” for fakes, and claiming that Aleppo was not under siege at the time. The other accounts tagged do not appear to have reacted.

This was not a major attack. It does, however, show the same methodology. Renieri retweeted the Panorama post, tagging a number of other users. Some of those users then sent hostile posts direct to Panorama.

Same Hits, Different Day

Journalists have not been the group’s only targets. On March 17, 2018, the director of Human Rights Watch, Ken Roth, shared an article in the New Yorker which analyzed the deaths of a number of critics of the Russian regime in the United States.

Fifteen minutes later, Renieri quoted the Roth tweet, and tagged many of the same accounts again. One minute after that, one of the tagged accounts, @2flamesburning1, replied directly to the Roth post which Renieri had tweeted, calling him an “idiot.”

As of May 24, @2flamesburning was not following Roth. The speed with which the account proceeded to attack him, once Renieri tagged it, suggests that the Renieri post was the immediate trigger.

According to a machine scan run with Sysomos, five of the accounts tagged by Renieri retweeted her post in short order: @MarcelSardo, @2flamesburning1, @VanessaBeeley, @Malinka1102, and @SueGrant54321.

Following on from these retweets, a number of accounts which follow the users in question added their own, largely personal, attacks on Roth.

These attacks came swiftly. The first was twenty minutes after Renieri’s post, and just five minutes after Beeley’s retweet; the other two followed within ten minutes.

A little over an hour later, another account, @dp1970at43, tweeted a particularly hostile reply. This user follows several of the accounts tagged by Renieri, but does not follow Roth, making it probable that their attention was drawn to the Roth post by one of the retweets of Renieri.

The trail here was less clear than in the case discussed above; however, it again appeared that the effect of the Renieri tweet, when retweeted by the users whom she did tag, was to steer a number of other hostile users towards Roth’s post.

A Long Campaign

Renieri appears to have used the technique of tagging other group members most frequently, and most effectively, but other members also used it on occasion.

For example, on December 18, 2017, Guardian reporter Olivia Solon published a feature-length article on the disinformation campaign targeting the White Helmets rescue group, a campaign in which Syrian regime supporters Vanessa Beeley and Eva Bartlett play a leading role.

This article appears to have particularly incensed the Renieri group, as it criticized two of their leading voices. Repeatedly, over the following months, they appear to have drawn one another’s attention to quotes of it — at least once, with an explicit call for harassment.

The action began early. The morning the article appeared, one account often tagged by Renieri, @bodhibrian, shared a post criticizing the Solon article, and tagged several other familiar users, including @VanessaBeeley, @RenieriArts and @Ian56789, alongside RT commentator Neil Clark.

The same account shared the same post again just over an hour later, this time calling Solon a “scribbler and swindler,” and again tagging Beeley, Clark and others. They do not appear to have responded, and the tweets were not liked or retweeted: these posts are of interest because they show another member of the group apparently trying to draw its attention, albeit without success.

The next morning, @SoniaKatiMota, another account which Renieri has often tagged, posted a pair of tweets about Solon’s piece, tagging Beeley and Bartlett. The latter of these was a direct warning to Bartlett that she was mentioned in the “criminal propaganda sludge;” it also tagged @RenieriArts, @2flamesburning1, and @malinka1102.

The purpose of the tweet was evidently to alert Bartlett; the inclusion of @RenieriArts, @2flamesburning1, and @malinka1102, who were not mentioned in the Guardian piece, appears to have been an attempt to attract the attention of other members of the network.

On this occasion, @2flamesburning1 did not respond; @malinka1102 and Bartlett had already posted their own comments, mocking the fact that Solon had protected her tweets. This suggests that @SoniaKatiMota’s warning was too late for relevance.

The attacks on Solon continued for some days. On December 20, Clark posted a tweet calling her article a “Russophobic hit piece” and accusing her of cowardice for protecting her tweets. “Russophobia” is a regular RT accusation against Kremlin critics, as @DFRLab has chronicled.

The same day, one of the experts whom Solon had interviewed, Professor Scott Lucas of Birmingham University, shared the Guardian article. A few hours later, another member of the Renieri group, @taigstaigs, replied that “You only add to @guardian’s disrepute”, and attached a photo which tagged, among others, Beeley and Renieri.

Only one of those tagged, @JohnDelacour, responded; again, therefore, this post is of interest for the way it shows different members of the group tagging one another in cases in which they are attacking critics.

Solon provoked the group’s ire again on February 6, 2018, when she ran an article on the renewed disinformation campaign against the White Helmets ahead of the Oscars. The previous year, a Netflix documentary about the group had won the Oscar for best short-subject documentary.

This time, Beeley was the first to respond with a mocking tweet. She tagged Solon and a number of other users. Most were pro-Kremlin communicators, such as the Russian Embassy in the UK, RT show host Afshin Rattansi, and Sputnik radio host John Wight; however, Renieri was also mentioned.

Renieri first replied to Beeley, then posted her own tweet, tagging Solon, together with Beeley and further members of the group.

On this occasion, several of the tagged accounts responded with their own mocking comments which also tagged Solon, and therefore would have appeared in her timeline. @Malinka1102 commented that Solon had protected her tweets again, “just like she did when she & @guardian published previous crap.”

@2flamesburning1 posted direct to Solon, accusing her of “mixing digital fantasy and reality,” and also tagging Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling, who has been a target for this group ever since she interacted with Aleppo girl Bana Alabed during the siege of the rebel part of the city in 2016.

Some of the attacks were particularly personal, and show that the group had spent some time researching her professional and personal past.

@EvaKBartlett quoted a lifestyle article Solon had written in March 2016, apparently to question her credibility. Group member @KevorkAlmassian shared a blog post (now private) about shoes which Solon had written in 2011, in the same tone. @Bickypeg later called her a “bimbo who writes about shoes.”

@KevorkAlmassian also posted an image of Solon at a party, again in an apparent attempt to question her credibility. The practice of using what is obviously a personal photo to attack Solon’s professional credentials further underlines the extent to which this should be considered a harassment group, rather than legitimate criticism of the content of Solon’s article.

Yet another round of attacks began in May 2018, after British Member of Parliament Matt Pennycook shared Solon’s December article and tagged her.

In response, Renieri tweeted a call for a “tsunami” of responses to Pennycook’s tweet, and again tagged members of the group. This can only realistically be viewed as an attempt to invite just such a “tsunami” from them.

The tsunami was not forthcoming. Beeley, @bsnews1 and @NeoTipPro had already replied. @Banjomarla replied directly to Pennycook, but merely challenged him to quote facts from the Solon article. The others remained silent.

Right to Reply

Before publication, @DFRLab gave these users the right to reply from our dedicated communications channel on Twitter, @DFRLabComms. In each case, we asked the users what their intentions had been in tagging one another. This was the first post, which typifies the series:

Few of the replies we received gave substantial answers or credible alternative explanations for their behavior. Most resorted to abuse and attempted mockery. Renieri again tagged other members of the group.

@Malinka1102 replied to Renieri’s tag. Her post suggested reporting @DFRLab for targeted harassment, without apparent irony.

Bartlett accused @DFRLab of “fake news,” without asking what news, exactly, we were reporting. Other users showed their wit and verbal dexterity in a variety of insults.

The attacks quickly became personal, as members of the group expanded their comments from the @DFRLabComms account to members of the @DFRLab team.

A few of the answers contained at least an element of substance. One of our posts asked @2flamesburning1 how the user had become aware of Ken Roth’s tweet, to which it replied with the “idiot” comment. The response accepted the right to reply, and justified its comment to Roth, but did not answer our question.

Renieri justified her call for a “tsunami” of comments to Pennycook by accusing him of insulting hundreds of people. This did not answer our question, which was concerned with the appearance that Renieri was inciting a “tsunami” of hostile comments to Pennycook.

None of these posts answered our main question, which was the users’ intention when they tagged one another. Lacking any arguments to the contrary, we therefore conclude that their intention was, indeed, to incite a wave (or tsunami) insults and abuse against the victims.

Conclusion

This cluster of accounts is active, aggressive, and coordinated. At key moments, and especially when accusations are made against the Syrian and Russian regimes or their supporters, group members share posts from the accusers, and tag one another.

One some occasions, though certainly not all, these tagged posts are followed by direct attacks on the accusers by members of the group, or their followers.

When such cases occur, the effect is to flood the Twitter space — and the target account’s notifications — with hostile, angry, and personal posts.

Anger and critical comment are part and parcel of debate on Twitter. However, these tagged posts go beyond that. They appear to be an attempt to gather a group of vocal users around critics of the Syrian and Russian regimes, to then shout down, humiliate or intimidate those critics.

The approach does, however, have its limitations. Publicly posting in this way betrays the size and composition of the group. By no means all the attempts led to such mobbing; sometimes, members ignored them almost completely.

Finally, it shows how small the group is. Renieri’s three posts on Stewart tagged just under fifty accounts — the largest collection around a single issue. These same accounts feature repeatedly in many of the attacks which journalists, NGOs and analysts who focus on Russia and Syria have suffered over the years.

This is not a massive online movement: it is a small, highly active and partially coordinated one which achieves its impact by clustering around its targets, and attempting to swamp the conversation.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.