#ElectionWatch: As Colombia Votes Again, Misinformation Flows

Legitimate campaigning was fused with false claims spread by political actors

#ElectionWatch: As Colombia Votes Again, Misinformation Flows

Legitimate campaigning was fused with false claims spread by political actors

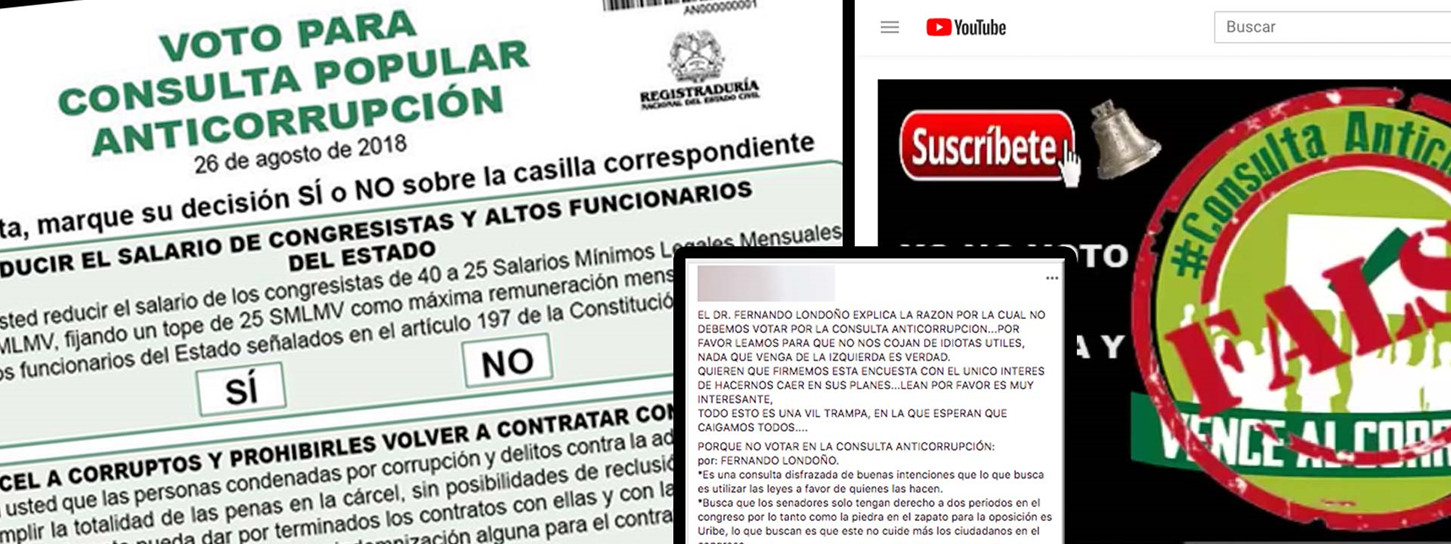

On Sunday, August 26, Colombians went to the polls again, this time to vote in a “popular consultation” on a series of seven initiatives intended to counter corruption. A significant share of the campaigning involved spreading misinformation — or countering it.

The consultation asked Colombians to vote on seven initiatives intended to crack down on Colombia’s endemic corruption. If approved, they would have strengthened punishment for convicted corrupt officials, improved the transparency of public offices and public contracts, imposed a maximum of three four-year periods for holding seats in public corporations — Congress, department assemblies (something like state legislatures in the United States), and city councils — and lowered the salary of Congress members and other high-ranking public officials.

The consultation was backed by both the president and the opposition, requiring a high turnout and a high vote to be approved, but failed to achieve the former. Disinformation aimed at suppressing the vote likely had a serious impact on the outcome.

The process that led to the vote was ongoing for more than one year and headed by the Green Party and its most visible leaders: former senator Claudia Lopez and Senator Angelica Lozano. The opponents of the initiative were mostly right-wing from the Democratic Center party, of President Iván Duque.

Turnout was crucial. To be counted as valid, the initiative required 30 percent of registered electors to vote, and each question must have a simple majority of votes in favor. This meant that some 12 million people had to cast their ballots, a demanding number in a country where non-traditional elections are not very popular. The last and highest profile examplde of a similar process, the peace plebiscite in 2016, had just over this same number of total votes. The consultation got 11.6 million votes, 500,000 votes below its needed threshold.

As often happens in Colombia, the issue became a contentious topic, and positions depended on which side of the polarized political landscape people were. While the left wing broadly agreed with its proposals and campaigned for its approval, an important sector of the Democratic Center was against it — even when President Duque himself publicly supported it and invited people to vote it.

Opponents of the proposals combined legitimate legal and political arguments with false claims to convince people not to go to the polls. This article will focus on the latter and show where are they being spread.

Legitimate Criticism — or Not

There were three main arguments against the consultation. First, some objections claimed that the proposals were well-intentioned, but could lead to undesirable outcomes. This was the position of some well-regarded jurists and researchers in the country, like Rodrigo Uprimny or José Gregorio Hernández, a former Magistrate of the Constitutional Court.

There were also political objections. Some right-wing opinion leaders, like former Bogota mayor Jaime Castro, said that the consultation was a way for Claudia Lopez to position her allegedly upcoming campaign for Bogota’s Mayor Office next year. Others believed that the election’s real intention was to improve Green Party’s position in the political landscape. While consultation supporters denied both accusations, they were not demonstrably true or false, as they were more instances of electoral rhetoric than concrete and verifiable claims.

Finally, there were false claims against the consultation, based on demonstrable lies and conspiracy theories. Two prominent ones circulated widely on Colombian social media. The first one said that the consultation was a way for the Colombian left-wing to put forward “a homosexual agenda” that would have made abortion legal, discriminated against heterosexual people, and forced Colombians to “raise [… their] children with homosexual foundations.” The consultation did not mention any abortion or gender issues.

The allusion to homosexuality was a reference to the sexual orientation of the bill’s main promoters, Lopez and Lozano, who for years were in a lesbian relationship together. This argument was also used in the campaign for the peace plebiscite, when false claims alleged that agreements with FARC imposed a series of obligations that threatened traditional Catholic beliefs, such as gender education in schools.

The Facebook post shown above also claimed that the proposal would restrict members of Congress to holding their seats for two four-year periods, and that this would have forced former president and right-wing leader, Senator Alvaro Uribe, to resign at the end of this legislative tenure. The real period it proposed was three legislative terms, and according to Senator Lozano, this would not have applied to legislators who were already serving in Congress.

Right-Wing Channels

Different postings of the same text — including its spelling mistakes — were shared widely on right-wing Facebook groups and pages, as this Facebook search shows (archived on August 23rd). It gathered significant engagement across many of them. For instance, one post (archived on August 23rd) on the group “Uribista de verdad” (“Real Uribe Sympathiser”) gathered 158 comments and 383 reactions, most of them positive. Another post (archived on August 23rd), in the group “Uribe, el mejor presidente que ha tenido Colombia” (“Uribe, the best president Colombia has ever had”) was shared 131 times and got 61 comments and 86 reactions. A third post, (archived on August 23rd), from the group “Voluntarios De Iván Duque Márquez Presidente” (“Volunteers of Iván Duque Márquez Presidente”) obtained 110 reactions, 20 comments, and 182 shares.

There was no evidence that this engagement came from inauthentic activity. A cross search of the activity of the text’s posters on different groups did not reveal any suspicious activity: the only pages they all liked in common was Alvaro Uribe’s official page, and a Spanish, 15-million-strong page named Fabiosa, devoted to viral content (1 / 2 / 3, archived 1 / 2 / 3). They have not commented or liked any post, image, or video in common.

The most likely explanation for them to have posted the same text in different groups is that they drew it from a common source, such as WhatsApp groups of Democratic Center sympathizers, or another right-wing group on Facebook. These cross-sharing practices are common in Colombia, and they have been identified by several researchers.

Another example of false claims against the initiative is a YouTube video published by the channel “Grupo Resistencia no FARC!” (“No to Farc! Resistance Group”). As of August 23, it garnered nearly 25,000 views and 153 comments.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=09vkVZ1fxME

Among other arguments, it stated that, if the consultation was approved, the salaries of all public officials would go down.

This was based on a chain of apparent logic. One of the measures in the proposal would lower the salary of members of Congress and other high-ranking officials. Since the wages for most public servers in Colombia are set as a fraction of those of Congress members, the video claimed that many people would get lower paychecks as a result. It also attempted to link the vote campaigners with the FARC guerilla movement in one of its last sentences:

“Let us stop being naïve while facing our murderers’ perversity.”

According to the vote promoters’ official website, this claim on salaries was a usual lie, and it was mentioned in several contexts that intend to dissuade people to vote. Understandably, it was likely that some voters ended up with the idea — or at least, with the doubt — that the initiative would have lowered their salary if it passed. The promoters said that, if it passed, Congress would have had to create a new regulation for “making sure that salaries of other officials […] would not be lowered.”

Analysis showed that the video was shared mostly on right-wing groups, such as “Unidos en contra del comunismo y el socialismo” (archived on August 23rd) (“United Against Communism and Socialism”). However, its most significant engagement seemed to come from user posts in their news feeds, as the sum of interactions from groups or pages was lower than the total aggregate.

Conclusion

These patterns of partisan sharing of misinformation are common in the Colombian political online conversation. The anti-corruption consultation was opposed by right-wing politicians who are rivals of the election’s promoters. Hence, right-wing social media spaces were places of a heavy opposition to it. Alongside legitimate arguments and the usual political banter, a significant amount of disinformation was published and circulated to dissuade people to vote for it.

Countering these lies was an important part of the campaign in favor of the consultation. This shows a greater awareness from political actors of the perverse effect disinformation can have in political debate; and is a resilience activity worth highlighting and encouraging.

Even though the actual impact disinformation had on the outcome is unclear, this is yet another warning of the vulnerability of Colombian information landscape in moments of political uncertainty. This stresses the need for Colombian information actors to build verification and resilience capacities, and the necessity of a greater commitment by politicians, political parties, and officials, to stick to better ideas and arguments on their debates and communications.

Jose Luis Peñarredonda is a Digital Forensic Research Assistant at @DFRLab.

#ElectionWatch Latin America is a collaboration between @DFRLab and the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center at the Atlantic Council.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.