#ElectionWatch: What Was Up with WhatsApp in Brazil?

The messaging platform was considered a main vector of disinformation in the country

#ElectionWatch: What Was Up with WhatsApp in Brazil?

BANNER: (Source: @DFRLab)

False claims disseminated on the messaging app WhatsApp during the 2018 Brazilian elections advanced the same narratives that circulated on other social media, including Twitter and Facebook.

Although the language on WhatsApp might have been harsher or shielded from more public scrutiny, the main topics were the same – electoral fraud, moral and religious issues, corruption, messages against the Workers Party (PT), and criticism of the media. The content indicated that propagators did not necessarily take advantage of the encryption mechanism of the platform to advance more blatant and aggressive narratives.

This suggests the platform is a potent vector for disinformation because of the way people engage with one another on it, as opposed to the content being categorically different. It is a trusted information environment, where users must know one another or self select into groups, which creates a predisposition to believe messages when sent.

WhatsApp was considered one of the main vectors of disinformation and misinformation in the Brazilian election that steered far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro to power. As the Facebook-owned platform uses end-to-end encryption, however, it is almost impossible to obtain metrics to verify this claim.

An analysis has revealed, however, that the most shared images on WhatsApp during the elections contained either false or out-of-context information. Research has also suggested that automation was used to spread content faster.

WhatsApp has 120 million active users in Brazil, one tenth of the 1.2 billion app users worldwide. The popularity of the app in the country is in part related to “zero rating” policies that allow users to use access the platform without tapping into their mobile data plans, which makes it a cost effective way to communicate.

WhatsApp’s end-to-end encryption makes monitoring and understanding content on the platform a difficult task. Researchers from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), however, were able to use their monitoring system Eleições Sem Fake (Elections without Falsifications) to analyze the use of the platform in Brazil.

The Eleições Sem Fake system monitored 347 groups that shared invitation links online. These groups could each house up to 256 users. Since there were more known public groups supporting Bolsonaro’s candidacy than any other candidate, these made up the bulk of groups monitored by the system. Some groups, however, comprised of people posting from both sides of the political spectrum.

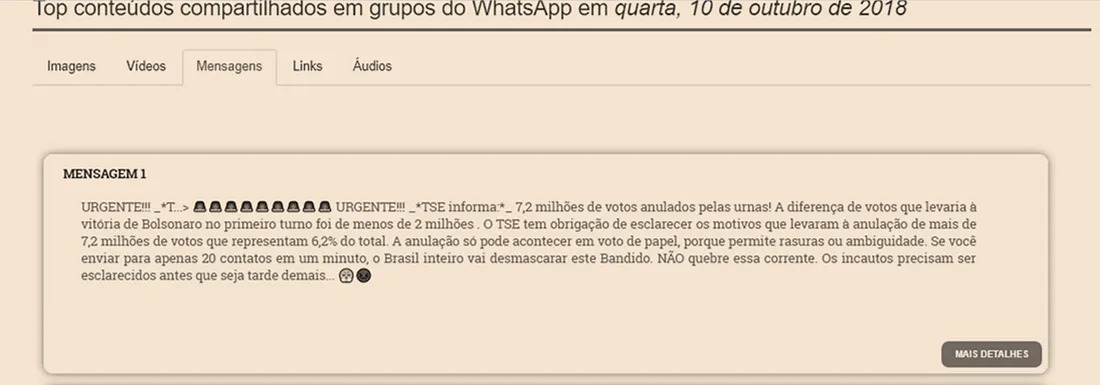

Throughout the election, Eleições Sem Fake published daily reports showing the most posted messages for the day and in how many groups a given message had appeared, separating each by medium (images, videos, texts, links, and audio notes).

@DFRLab and the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center analyzed the most shared messages, as available from Eleições Sem Fake’s daily reports, between September 30 and October 28, when the runoff took place. As the system does not allow for downloading the entire database, the most prolific content had to be analyzed and verified using the top-three messages from each day. After classifying the information by type of narrative and excluding messages in support of Bolsonaro’s candidacy, the most common posts regarded electoral fraud, moral issues, and anti-PT content.

Electoral Fraud

One of the most disseminated narratives on WhatsApp regarded claims of electoral fraud. Jair Bolsonaro fueled this narrative, even before the elections took place. Bolsonaro is a vocal critic of electronic voting, which is used nationwide in Brazil, and frequently voiced his concerns about the possibility of fraud. The electoral court decided that Google should take down at least one video in which Bolsonaro raised suspicions about fraud without showing evidence to support his case.

On a single day, a text message claiming Brazil’s top electoral court had cancelled 7.2 million votes was shared more than 700 times in the WhatsApp groups analyzed. The number being propagated, however, actually referred to people who had voted null, wherein a voter selects a box not associated with any candidate.

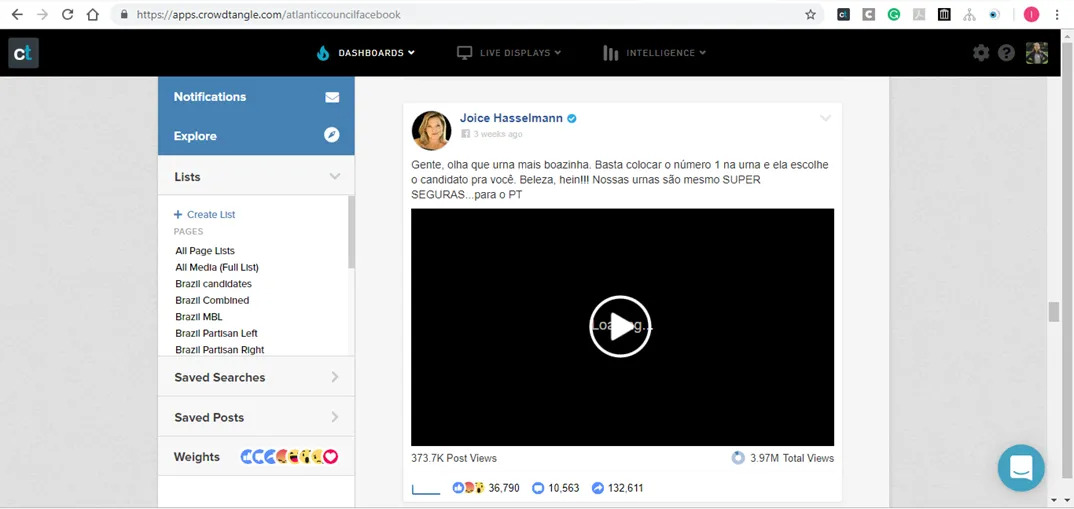

Claims of electoral fraud also made up a large part of the disinformation circulated on Facebook and Twitter. On October 7, the day of the first round of voting, a video was disseminated portraying a person trying to choose Bolsonaro on a voting machine. Bolsonaro’s ballot box number was 17, and that of his rival, Fernando Haddad, was 13. When the person pressed “1” in the machine, it allegedly resulted in an automatic vote for Haddad. The electoral court denied the accusation and showed in a video that another person, not captured by the camera, was pressing the “3” after “1.”

The video with the false claim was amplified by Bolsonaro’s son, Eduardo Bolsonaro, who published it on his Twitter account. He later deleted it. Joice Hasselmann, an elected deputy from Bolsonaro’s party, also shared the video on her Facebook page, which was viewed 3.97 million times. The video was also shared on WhatsApp.

Moral and Religious Issues

Another debate that circulated around the time of the election regarded moral and religious issues and was rooted in a controversy that took place while Haddad was the country’s minister of education. In an effort to help tackle homophobia in Brazil’s classrooms, in 2011, the government floated the idea of distributing educational videos and booklets to schools.

Conservative members of the National Congress, however, claimed the material pushed students into homosexuality and labeled it the “gay kit.” The ensuing pressure drove then-president Dilma Rousseff (of the PT) to bar the distribution of the material.

During the 2018 election, the “gay kit” narrative was exploited against Haddad on WhatsApp as well as on open social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook. Bolsonaro himself often repeated that Haddad was the “father” of the gay kit.

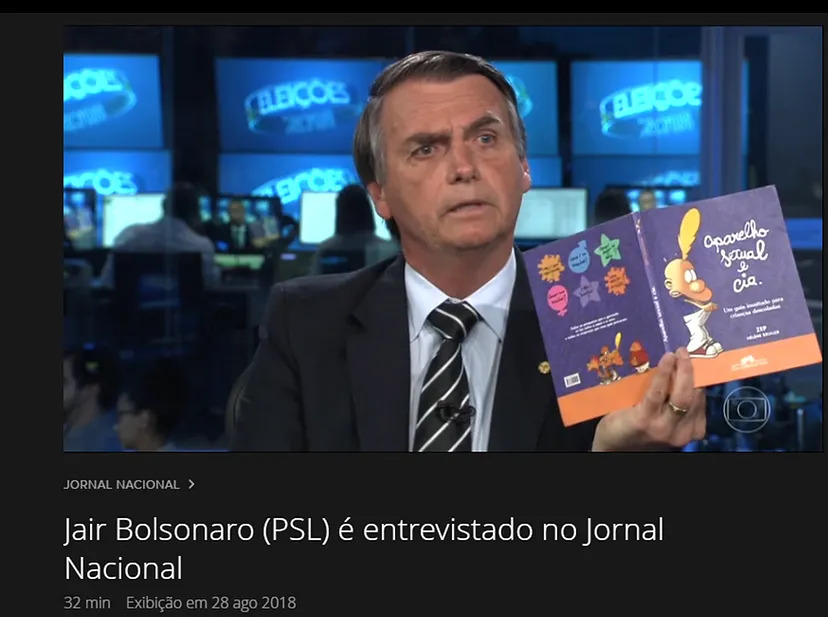

In an interview with TV Globo, the most watched news broadcast in the country, Bolsonaro showcased a sexual education book that he claimed to be a part of the “kit.” Because the book was not, in fact, a part of the education curriculum and therefore the claim was false, Brazil’s electoral court ruled that six videos in which he made the same allegation be removed from Facebook and YouTube.

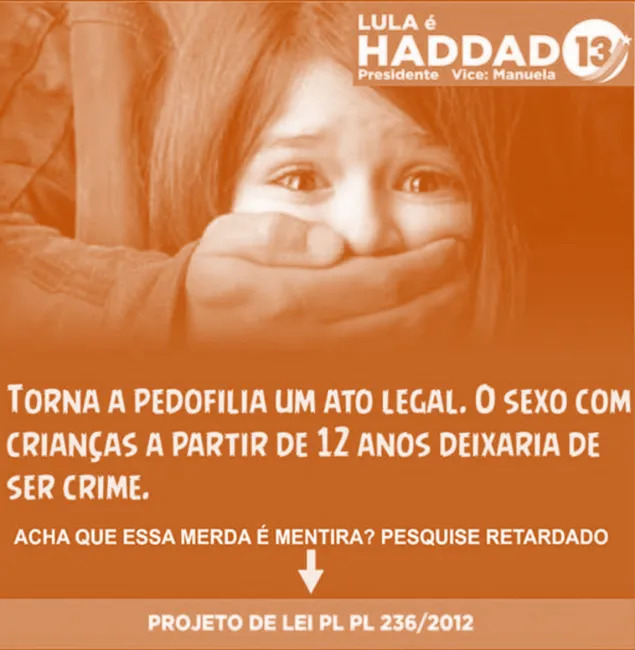

One of the most infamous false claims on this topic, broadly shared on many WhatsApp chains, asserted that, if elected, Haddad would distribute erotic baby bottles in daycares. These chains also claimed the PT candidate would make pedophilia legal in the country.

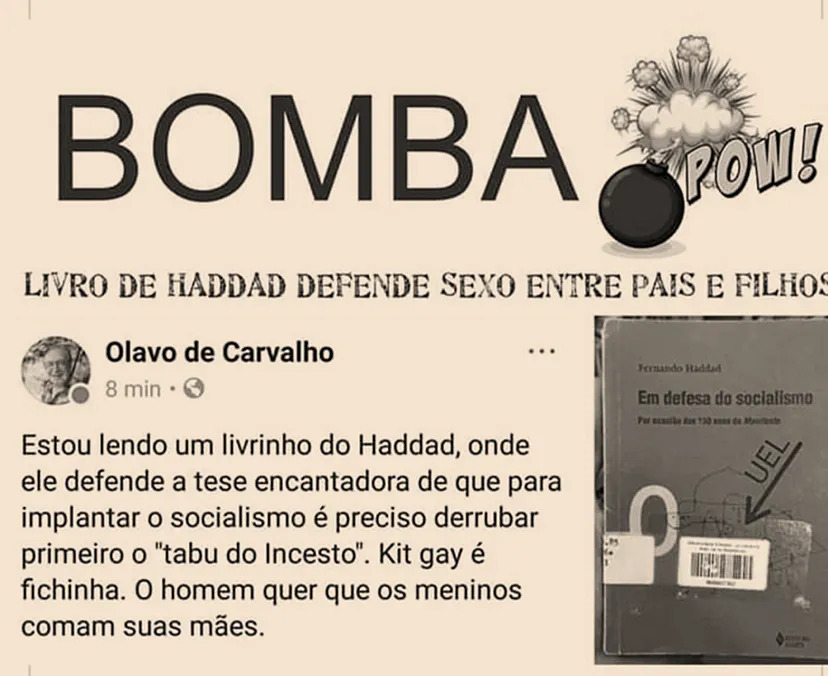

One prolific chain had its origins on Facebook. The conservative philosopher and conspiracy theorist Olavo de Carvalho wrote that, in his book Em defesa do socialismo (In Defense of Socialism), Haddad had written that incest was normal. One of Bolsonaro’s sons, Carlos, shared the comment. Later, Carvalho deleted the post and said that was not what the book said “literally.” Carvalho was also one of the main amplifiers of the Ursal hoax in Brazil, as reported earlier by @DFRLab.

Messages Against the Workers Party (PT)

Messages against the Workers Party (PT) widely circulated on WhatsApp throughout the electoral cycle. These narratives were framed in various ways, but most often painted the PT and its members as corrupt or communist.

The PT governed Brazil between 2003 and 2016, when president Dilma Rousseff was impeached for mismanagement of funds amid a political and economic crisis. The crisis is in part connected with Operation Car Wash, the corruption investigation that has implicated many of the country’s political and economic establishment over the past few years.

The party’s most prominent leader and then presidential frontrunner, former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, was jailed in April 2018 on charges of corruption and bribery. His candidacy was officially barred in August by the electoral court following subsequent appeals and convictions.

The PT claimed it was disproportionally affected by the investigation. This claim was repeated by the party after Sergio Moro, the judge spearheading the investigation, accepted the post of Minister of Justice in Bolsonaro’s administration.

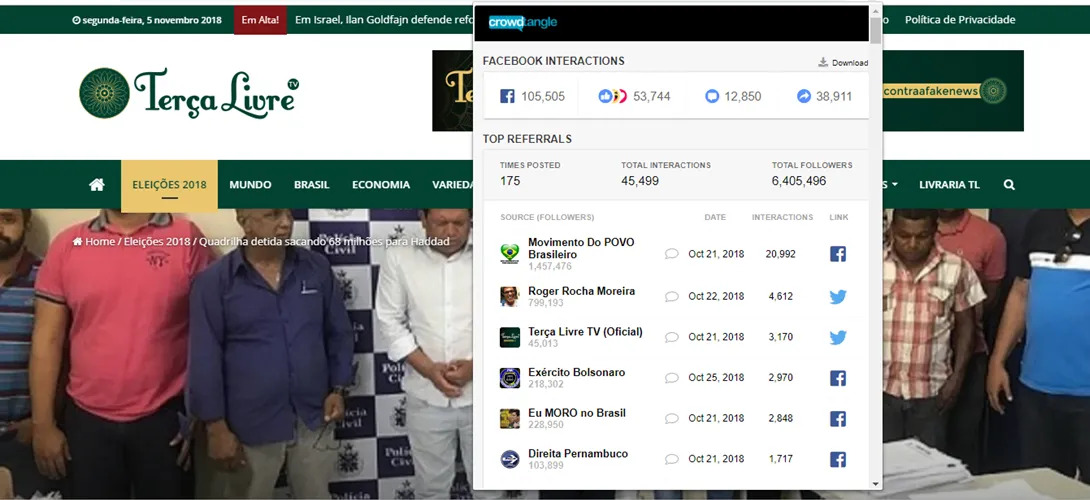

One of the most shared images of the Eleições Sem Fake system in the second round was of a check of 68 million reais (approximately $17 million USD) that allegedly was part of a corruption scheme to benefit the PT. The police denied the money was connected to the PT.

The image of the check was shared 114 times on October 23, 2018, per the Eleições Sem Fake system. This hoax was amplified by hyper-partisan websites such as “Terça Livre,” an outlet in support of Bolsonaro. According to Crowdtangle, the article received 110,000 interactions on Facebook.

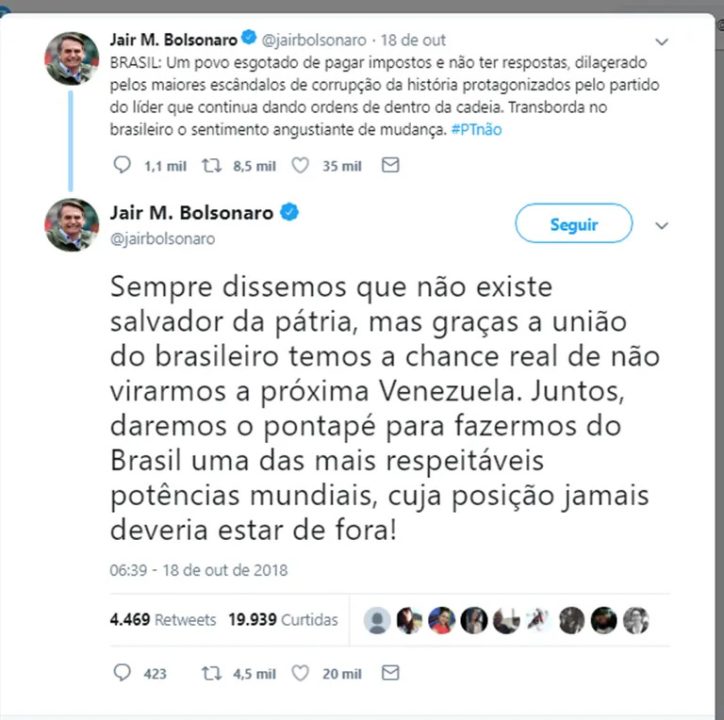

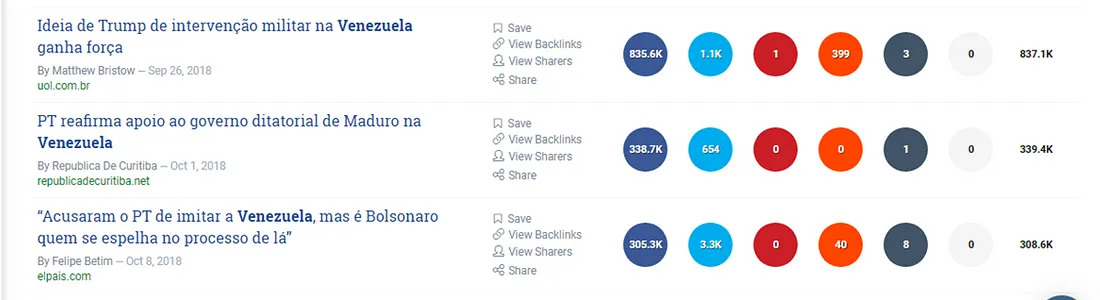

Messages claiming that the PT was communist, and that Brazil would become a new Venezuela if the party won, were also popular. The PT is a center-left party and, during its 13 years in power, had not adopted any perceptually communist policies. The party, however, has officially supported Venezuelan leaders Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro. Haddad, however, stated in August that Venezuela was not a democracy.

The Communist narrative was amplified by Bolsonaro and by pro-Bolsonaro partisan media. Bolsonaro often claimed on his social media accounts that Brazil would become Venezuela if the left won.

Pro-Bolsonaro media also contributed to the spread of the narrative. The second most read article with the word “Venezuela” in the electoral period was from the pro-Bolsonaro website República de Curitiba (Curitiba Republic, in reference to the city where the investigators of the CarWash probe are based). The headline claimed that the PT had “reaffirmed support for Maduro’s dictatorship” in Venezuela. The article was published one week before the first round and said the statement had been made by the PT “recently,” while the party had actually made the statement one year prior.

Another misinformation campaign was broadly disseminated allegedly showing famine in Venezuela. One of the most widely shared pictures portrayed a man starving and a caption saying that could happen in Brazil if the PT won the presidency. The image, however, was originally taken in Syria.

Anti-media Content

Brazil’s traditional news outlets were also targets of criticism by Bolsonaro and his supporters throughout the campaign. The president-elect denounced articles with accusations against him as “fake news,” mainly calling out Globo, the main broadcaster in the country, and Folha de S.Paulo newspaper.

Two instances stood out as especially contentious during the campaign. The first happened around the rallies in favor of and against Bolsonaro that took place one week before the first round. On WhatsApp, supporters claimed the media were altering images and footage to insinuate there were more people in the anti-Bolsonaro protests, as reported by @DFRLab.

During the second-round campaign, another clash between the media and Bolsonaro happened when Folha de S.Paulo published an article stating that a group of businessmen were paying to broadcast anti-PT messages on WhatsApp. As of December 17 the claim was being investigated by the police. Bolsonaro said the newspaper had published “fake news” against him. After that, he adopted a strong position against Folha, promising to cut government ad spending to the newspaper and saying the newspaper “was over.”

On WhatsApp, the clash translated into boycotts of media outlets. Messages were spread advising readers to cancel their subscriptions to newspapers.

In the case of Folha, after the article was published, a campaign directed supporters to send messages to Folha’s WhatsApp number — as part of their fact-checking effort, many newspapers provided a number to which readers could send chains with possibly inaccurate or incorrect information to be verified. From October 19 to October 23, more than 220,000 messages were sent to the number, according to the newspaper.

Conclusion

Disinformation circulated on WhatsApp followed similar narratives that appeared on Facebook, Twitter, and other social media. Many such stories were amplified by Bolsonaro himself. Three important conclusions can thus be drawn.

First, the research suggests WhatsApp is part of a larger disinformation environment and cannot be analyzed in isolation. Even messages that apparently were created on WhatsApp had their origins in narratives circulating outside of the platform, and often traveled between platforms. WhatsApp does not function in isolation, and messages usually are not restricted to the messaging app.

Second, WhatsApp’s intimate nature, in connecting friends and families within a private and encrypted setting, seemingly played a more important role in the spread of misinformation than the types of narratives themselves. When users received messages from family and friends on WhatsApp, they tended to trust said messages more than when they encountered them on other social media.

Finally, the similar nature of the narratives shared on WhatsApp and of those shared on open platforms like Facebook and Twitter outline a potential path for tackling disinformation on WhatsApp. To strengthen digital resilience, explaining the narratives behind false claims may be more effective than debunking each piece of disinformation. This will enable digital consumers to interpret each case more critically and to disregard independently the ones backed by false narratives.

#ElectionWatch Latin America is a collaboration between @DFRLab and the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center at the Atlantic Council.

Follow along for more in-depth analyses from our #DigitalSherlocks.