#DigitalResilience: Where Is Armen Gasparyan’s Audience?

Sputnik’s political show on YouTube and Facebook engagement falls short

#DigitalResilience: Where Is Armen Gasparyan’s Audience?

Sputnik’s political show on YouTube and Facebook engagement falls short

A new Sputnik show on YouTube and Facebook, in which pro-Kremlin expert Armen Gasparyan discusses current events in international affairs, yielded lower engagement than other content on Sputnik’s YouTube and Facebook channels.

In August 2018, @DFRLab analyzed how Sputnik used short, entertaining, and apolitical videos by TOK, a Kremlin-owned Rossiya Segodnya brand, to grow its audience. It appears that political content on Sputnik performs worse than other content, including entertaining TOK videos. Gasparyan’s content serves as another example of this trend and receives notably low traffic.

Gasparyan is based in Russia, but Sputnik published episodes from the Gasparyan’s show in nine out of 14 countries where it reports in Russian. More of Sputnik’s Facebook followers in the Baltic states viewed the episodes than its followers in the Caucasus.

Gasparyan’s show is another example of Kremlin media producing content designed to convince uncritical viewers, in part using of logical fallacies spun as facts. This example is unlikely to succeed, given its low rate of engagement.

Armen Gasparyan

Armen Gasparyan is a pro-Kremlin expert on international politics and history. He positions himself as a publicist, political scientist, and radio anchor on Vesti FM and Sputnik on Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. On his website, Gasparyan mentions that he is persona non grata in Moldova; is listed on Mirotvorec, a controversial public Ukrainian database of its individuals seen as supporting the Kremlin’s military operations in Ukraine; and that pro-Western NGO Forum Svobodnoy Rossii (Free Russia Forum, from Russian) listed him as a “leader or an active member of disinformation troops” on “Putin’s List.”

In August 2018, a marginal Latvian political party Par Alternatīvu (For an Alternative, from Latvian) suggested his candidacy for the Latvian Ambassador to the United Nations. He wrote on Facebook:

“It is not a joke…They talked to me and I agreed.”

In September 2018, the Saeima passed him over for the position, instead selecting Andrejs Pildegovichs, a former Ambassador of Latvia to the United States.

The Show

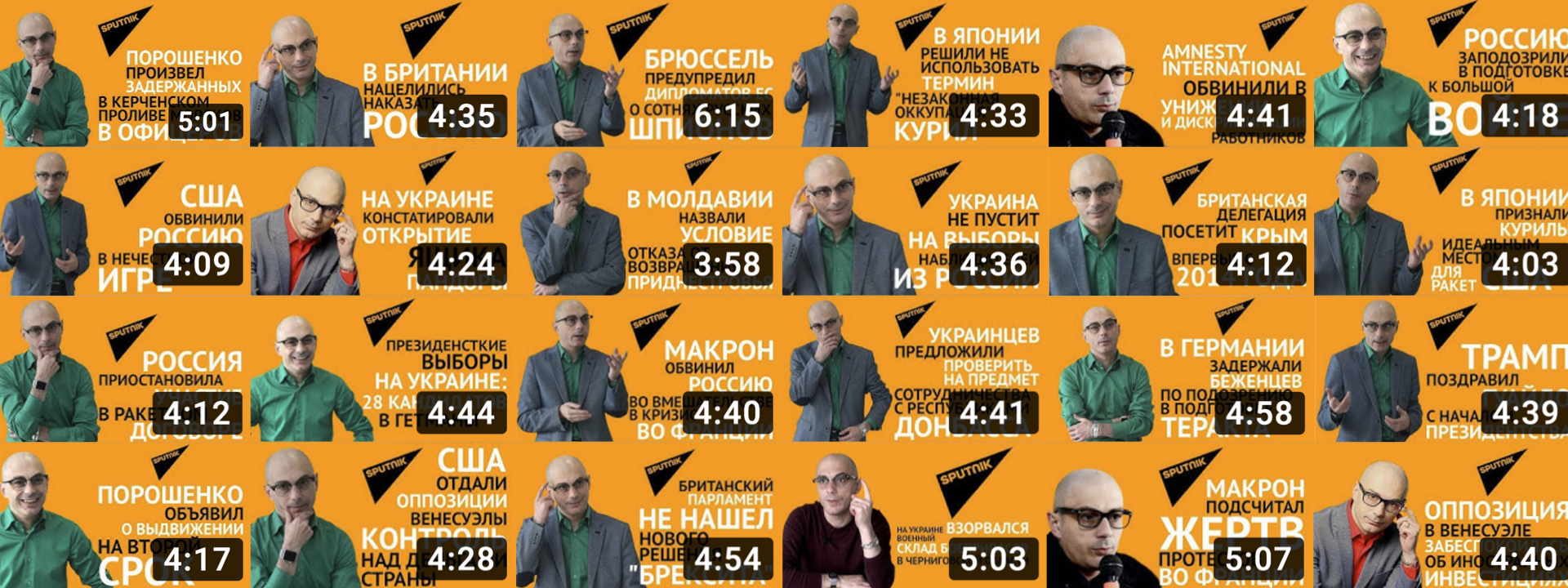

Sputnik announced Gasparyan’s show “Nablyudenie” (The Observation, from Russian) on April 26, 2018. Since that time, the creators of the show have produced 233 videos.

The episodes tend to run from three to six minutes and feature Gasparyan’s view on international affairs, especially those that are of interest in Russia, including: the Sergei and Yulia Skripal poisoning in the United Kingdom in March 2018; the Ukrainian Orthodox Church’s separation from Russia; and protests against high fuel prices in France. Below are the most common themes that Gasparyan covered in his episodes.

Ukraine and Ukraine-related topics were the show’s most popular and were discussed almost twice as often as everything else. The United States and United Kingdom were the next two most frequent topics. Gasparyan also often focused on other European countries and, particularly, the Baltic states. On top of country-specific themes, he talked about NATO, the Syrian war, or the World Cup in Russia all about the same amount.

Most videos include a short summary of the news with an emotional spin that was often conveyed using logical fallacies.

The Fallacies of Armen Gasparyan

As previously reported by @DFRLab, the use of logical fallacies is a favorite technique of Kremlin-backed and Kremlin-aligned media, and Gasparyan is no exception. The case of the Ukrainian ship captured by Russia in the Kerch Strait on November 25, 2018, is a good example of his portrayal of current events.

In a video published a day after the incident, he said:

Two weeks ago I told you that Pyotr Alekseevich Poroshenko will cancel presidential elections, because no one participates with such a bad popularity rating. The reason for that will be a provocation of some kind. Here you go — the Kerch Strait.

After the incident Poroshenko indeed initiated martial law for 60 days, but the Ukrainian Parliament decided to limit it to 30 days, so as not to affect elections set for March 31, 2019, and to restrict it to only the ten regions that border Russia. On November 27, 2018, Gasparyan updated his interpretation on November 27, 2018, by using a straw man argument to mischaracterize the reasons for introducing martial law in particular Ukrainian territories.

…martial law does not apply to the whole country, as Poroshenko wanted, but in very particular territories. Turns out, all of them are border Russia or are in areas where the Russian world has influence and Ukraine is fighting with it. I could not remember what the map of those territories reminded me of. Then, oh my God, I remembered — it is a typical Ukrainian voters’ map before Maydan. So, martial law is where no one loves Stepan Bandera, when it is necessary to oppress the Russian Orthodox Church. You and I understand why it is being done.

In using a straw man, Gasparyan first attacked the argument by mischaracterizing it, which then makes it easier to negate. More specifically, he started by mischaracterizing the area affected by martial law as overlapping with electoral maps; he then attributed these territories with supporters of Stepan Bandera, a leader of Ukrainian Nationalist Movement during the Second World War.

On November 27, the United Nations rejected Russia’s provisional resolution for the incident. Gasparyan subsequently compared the rejection to an unspecified action before World War II and painted a generalized, alarmist, and historically distorted picture of the consequences after World War II. He said:

It is not as important that the UN Security Council did not approve Russia’s proposal. Another thing is important. […] You know, the world has already seen this all. Before World War II, when there was no United Nations but there was a League of Nations, the same happened. It all ended quite tragically. The world was soon dragged into the orbit of the World War II. Millions of people died. Nazi war criminals were punished, because they started the war […] but no one punished the decision makers from the League of Nations who pushed the world to war.

On November 29, 2018, Gasparyan touched upon the subject again and provided his view on the Kerch Strait ship capture. He said:

People defiantly intruded into the territory of Russian Federation. They categorically did not want to respond to the demands of Russian authorities. They got what they deserved. Once again I emphasize — despite us being totalitarian Mordor […] we are democratic. We did not sink these floating buckets, the so-called Ukrainian Fleet. We just arrested the people, interrogated them. They gave their testimonies, which are not secret, they are public — everything was done as in a democratic country.

His (sarcastic) reasoning included a false dilemma (or either/or) fallacy by limiting possibilities to only two options — it was either sinking the ships or arresting the crew — when there were more options, such as not attacking the Ukrainian ships in the first place.

Content Dissemination Strategy

Sputnik publishes episodes of the show on its YouTube and Facebook pages in the countries where it reports in Russian systematically.

From July 2 until early October, Sputnik published one episode every Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday. On October 8, the number of episodes published per day jumped from one to three episodes. There was some fluctuation in this more aggressive publishing strategy from October 22 until November 15, but the trend remained mostly steady until the end of 2018.

Taking a month-long sample starting from the time of the ship capture, @DFRLab analyzed Gasparyan’s publishing pattern on Facebook from November 26, 2018, until December 19, 2018. Sputnik has local presence in Russian language in 14 countries. @DFRLab identified nine countries where Sputnik posted or cross-posted episodes on Facebook. It was done in Armenia, Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan. Cross-posting is a feature Facebook introduced in 2016. It allows for a consolidated number-of-views count across all instances of the video, which means the total number of views is the sum garnered by all pages that cross-posted the same video. Overall, @DFRLab identified 39 episodes during this time. Not all Facebook pages published all of the episodes.

The Russian version of Sputnik Lithuania cross-posted all 39 videos, Sputnik Kazakhstan cross-posted 35 videos, and Sputnik Latvia cross-posted 34 videos. Sputnik Uzbekistan, which is broadcast in Uzbek, cross-posted just six videos. Sputnik Belarus posted 15 videos without cross-posting them.

The Underperformance

The average view count of the show’s YouTube videos was 4,894 times. It is roughly 26 percent less than Sputnik’s YouTube channel gets on average. As of January 2019, the channels average view count for a single video was 6,643 views.

The most viewed video garnered 95,611 views and featured Russian football players Alexander Kokorin and Pavel Mamaev attacking a driver for TV channel Perviy Kanal Vitaly Solovchuk and using a chair to beat up Denis Pak, Director of the Automotive Industry Department of the Ministry of Industry and Trade, and Sergey Gaysin, Director General of FSUE Nami. [GB1] [NA2]

The analysis of videos on Facebook shows that the episodes had higher audience engagement in the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) than in the Caucasus (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan).

For comparison, since October 2018, the most popular video on Sputnik Lithuania and Sputnik Estonia in Russian was a video about a dead whale in Madrid. The most viewed video on Sputnik Latvia in the same time period was about a doctor who figured out the reason for patients dying in early mornings. In Kazakhstan, Sputnik’s most popular video was about a man who reached out to Beatles singer Paul McCartney for help to restore a burnt house. In Uzbekistan, the most viewed video on both Sputnik’s pages (in Uzbek and in Russian) was about the terrible conditions in which Afghan refugees live. In Tajikistan, the most viewed Sputnik video was about a famous Turkish chef cooking for Ramzan Kadyrov, leader of Chechen Republic.

The average number of views for all videos posted on Sputnik’s Facebook pages since October 2018 is two or three times larger than the average view count of Gasparyan’s show.

The trend line of the episode view count from November 26, 2018, until December 19, 2018, showed a steady or downward trend.

Conclusion

Pro-Kremlin international politics expert Armen Gasparyan, in providing editorial views on international affairs, focused on Ukraine, the United States, and the United Kingdom more than other countries. He used logical fallacies to explain international affairs, including in defending Russia’s action in the Kerch Strait when it captured a Ukrainian ship.

Sputnik distributed his show on YouTube and Facebook in systematic way and published episodes on Facebook in nine out of 14 countries where it has local news coverage in Russian.

The show performed worse both on YouTube and Facebook than the rest of Sputnik’s content. More Facebook users viewed the show in the Baltic states than in the Caucasus.

The perceived target audience of Armen Gasparyan’s show is Russian-speaking populations across the former-Soviet Union that are — in many cases — a potent political minority in their respective countries. While the show’s engagement efforts currently fall short, its systematic approach demonstrates Kremlin-aligned amplifiers’ long-term focus on information influence.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.