Russian “Info-War” Pages Removed

Facebook removed pro-Kremlin pages run by fake accounts connected to a ‘crypto-jacking’ site

Russian “Info-War” Pages Removed

BANNER: (Source: @Kanishkkaran /DFRLab)

Facebook took down a network of self-proclaimed Russian “info-war” pages and accounts on May 6, 2019, ruling that they had used fake accounts to run their public-facing activities.

Social-media platforms have taken down multiple clusters of Russian fake accounts over the past two years. The eight pages Facebook removed on May 6 claimed to be Russian activists, and largely posted in Russian, about Russia’s role in the conflicts in Ukraine and Syria.

There was insufficient open-source evidence to conclude whether they were connected to Russian authorities.

The pages pointed users toward three websites that in turn shared content from a variety of state propaganda outlets, including RT, Zvezda TV (the Russian Army broadcaster), and a range of unofficial Kremlin supporters. Evidence from the websites, however, suggests that they were designed to monetize propaganda by generating ad revenue and spreading malware.

The pages were not especially popular: the most-followed page, created in 2012, had just over 21,000 followers. All but one of the others had under 2,000.

Announcing the action, Facebook said:

“We removed 97 Facebook accounts, Pages and Groups that were involved in coordinated inauthentic behavior as part of a network emanating from Russia that focused on Ukraine. The individuals behind this activity operated fake accounts to run Pages and Groups, disseminate their content, and increase engagement, and also to drive people to an off-platform domain that aggregated various web content.”

This post analyzes the first of the two sets removed in the May 6 takedown, including the Facebook pages and the websites closest to them.

Self-Proclaimed “Info-War”

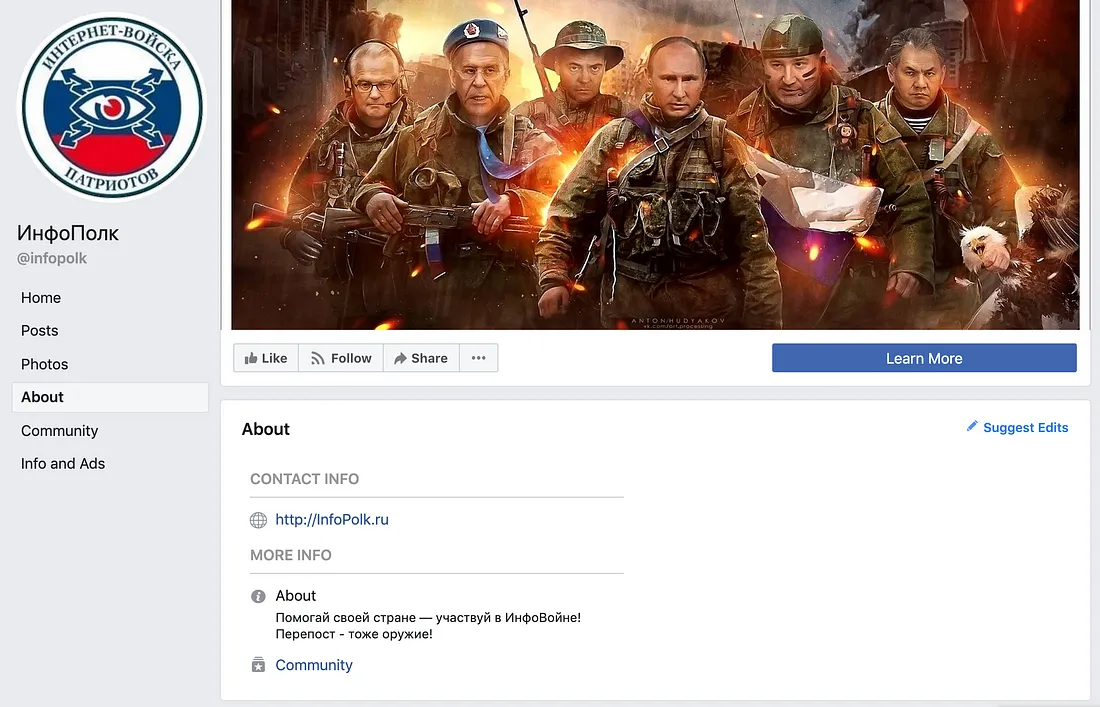

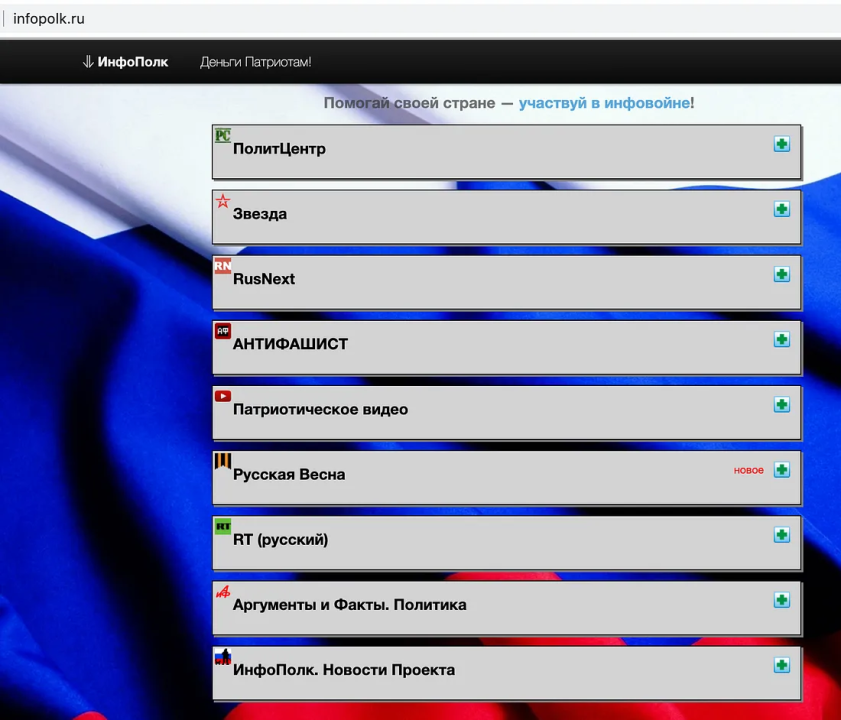

Four of the eight pages were linked to a website called infopolk.ru. The name translates from Russian as “info regiment,” and the website and associated pages called on users to “take part in the InfoWar.”

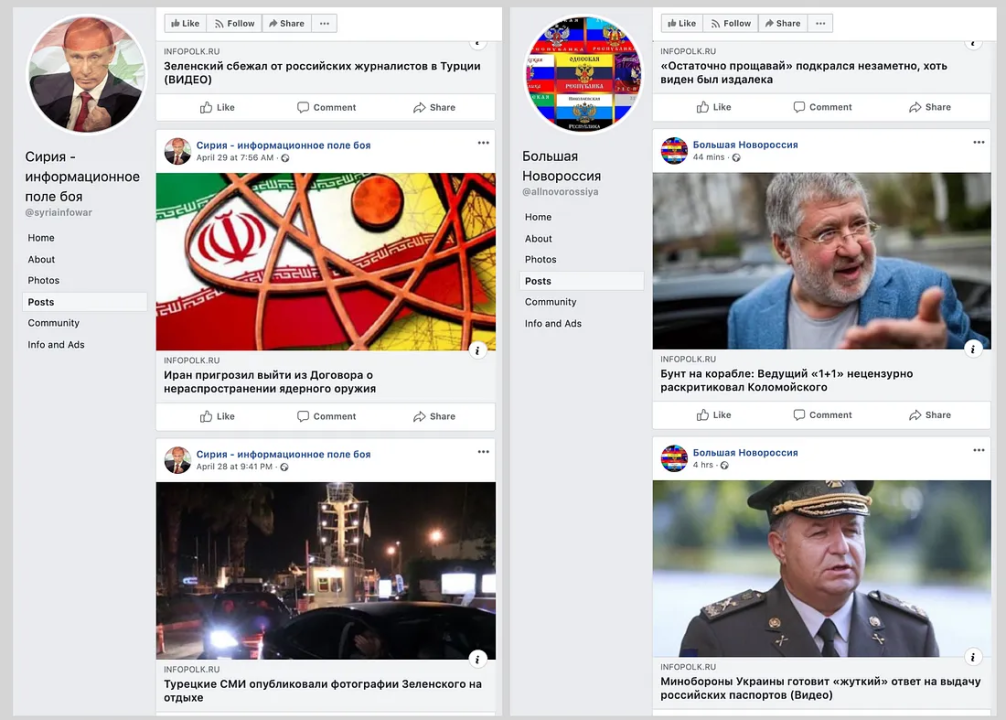

One of the pages was called simply @infopolk. The others were called @syriainfowar (dealing with the Russian operation in Syria), @ykrainanasha (“Ukraine is ours”), and @allnovorossiya (the name “Novorossiya” is sometimes used to refer to the Russian-backed separatist regions of Ukraine). Each page mainly posted articles from the infopolk.ru website.

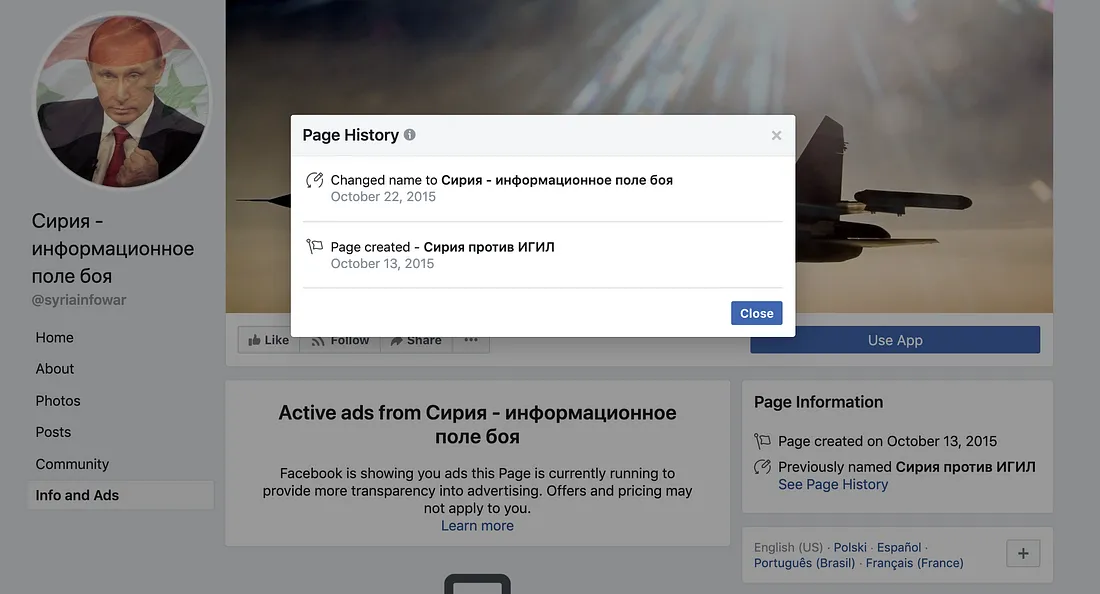

The Syria-focused page was initially called “Syria against ISIL,” referring to the Islamic State terrorist group. This was changed 10 days later to “Syria — information battlefield.” The change reflects the Kremlin’s propaganda of the period: this initially presented the Russian operation as targeting ISIS but changed to more generic language when open-source researchers revealed that almost none of Russia’s early air strikes had hit the terrorist group.

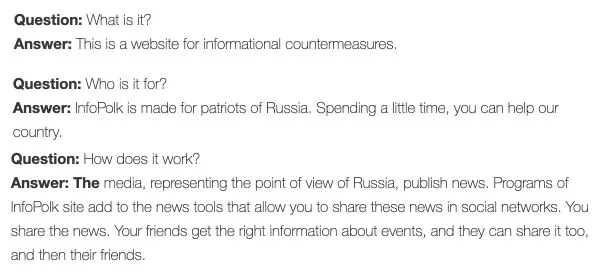

The infopolk website reproduced content from a range of Kremlin and pro-Kremlin sources, including RT’s Russian service and Zvezda. The banner at the top of the website gave the same call to arms as the Facebook page: “Help your country — take part in the infowar!”

The website’s frequently asked questions explained that it was set up for “patriots of Russia” as a “website for informational countermeasures,” especially sharing “media which represent Russia’s viewpoint.”

Apps, Malware, and Cryptocurrency

The infopolk.ru website directed users to a range of Kremlin and pro-Kremlin websites and also featured add-ons that would ostensibly allow the user to share the content instantly across a range of social media.

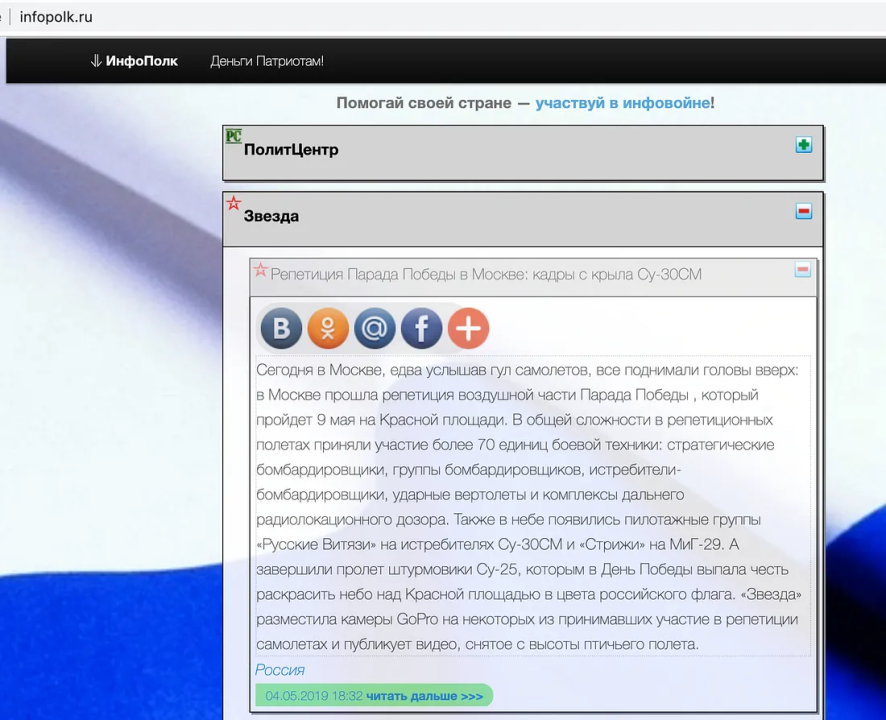

It also offered Android users a downloadable app that would allow them to do the same directly from their devices by scanning a QR code.

The website was also running malicious code to hunt for cryptocurrencies on the computers of website visitors.

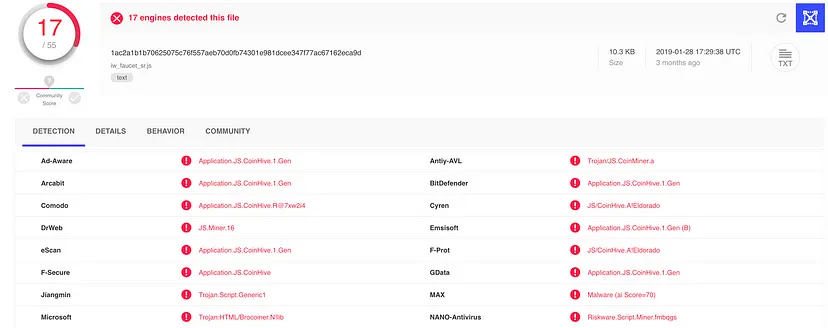

According to an open-source scan of the website using VirusTotal, an anti-virus aggregator, a downloadable file was found with malicious code — Application.JS.CoinHive.1.Gen, also known as Coinhive. According to security firms, Coinhive is one of the top malicious threats to web users who use the Monero cryptocurrency. The code, which can be planted on a website without the user’s consent, steals the visitor’s processing power in a bid to mine bits of Monero cryptocurrency. This technique is known as crypto-jacking — unauthorized use of a website user’s computer to mine cryptocurrency.

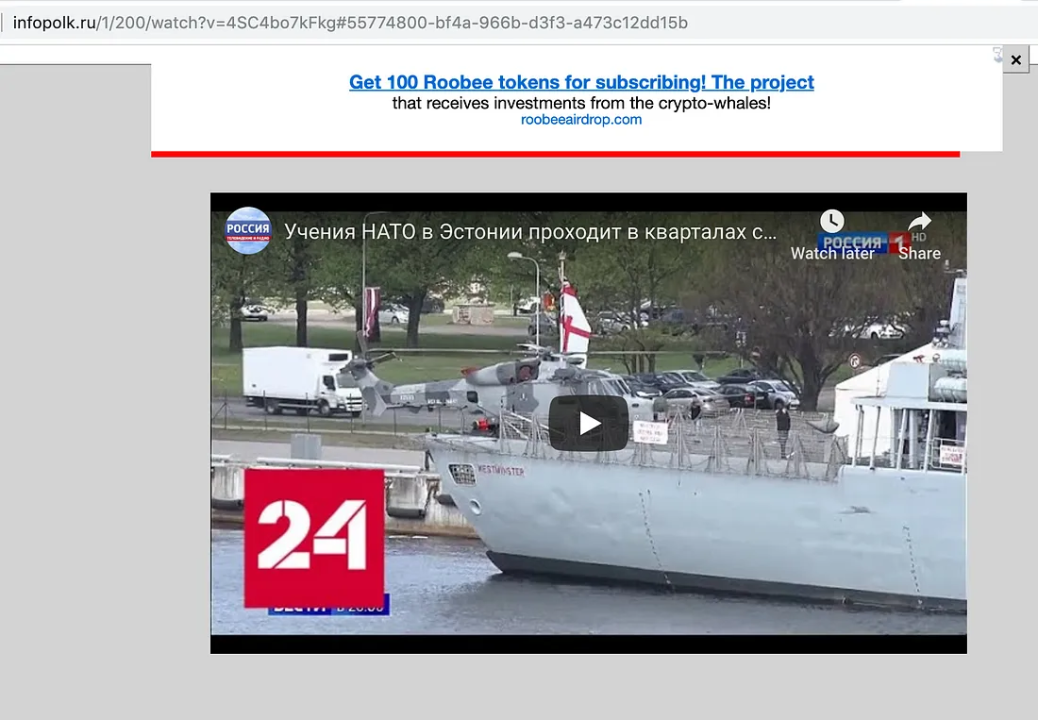

The infopolk website also embedded ads around the YouTube videos it shared, especially regarding cryptocurrencies. An accompanying message claimed that this was to fund the website, as all its managers were volunteers.

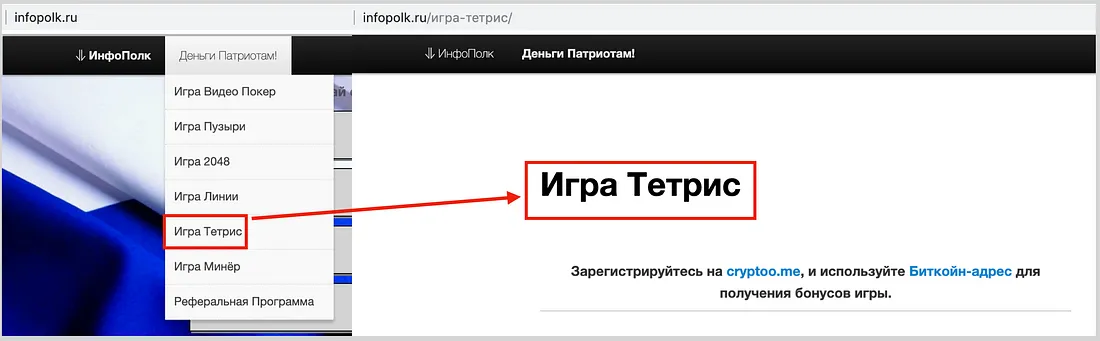

One of the site’s drop-down menus was labeled “Money for patriots!” and offered a variety of computer games, from video poker to Tetris. In each case, clicking on the link led to the message, “Register for cryptoo.me, and use your bitcoin address to get game bonuses.” Cryptoo.me is a cryptocurrency microtransactions service.

Taken together, these indicators suggest that the infopolk.ru website was at least partially, if not wholly, designed to generate revenue, especially in cryptocurrency. And by accident or design, it also included malware.

Russian in Ukraine

Two of the other pages in the takedown focused on Ukraine, but were linked to separate websites.

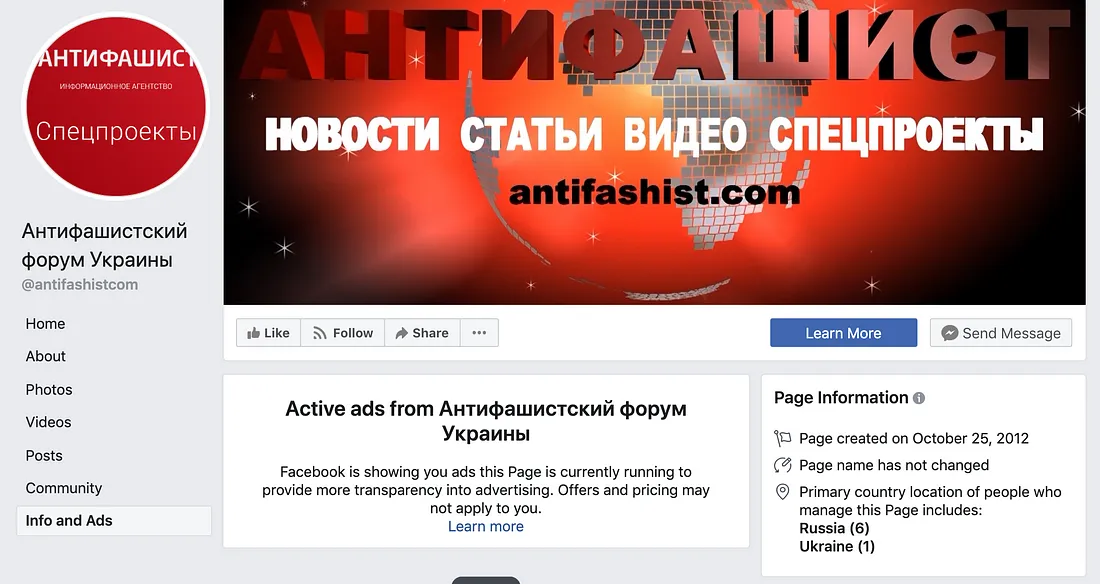

One page, @antifashistcom, called itself the “anti-fascist forum of Ukraine;” almost all of its page managers were located in Russia. This was the oldest page in the network, created in October 2012 and had the largest following, at just over 21,000.

In similar fashion to the infopolk pages, this page repeatedly shared content from one website, antifashist.com. The posts mainly concerned Ukrainian and Russian politics, typically from a pro-Russian point of view.

The content appeared to be largely copied from other sources. For example, this post on Facebook, about a journalist being beaten up in the Ukrainian town of Cherkasy, led to this article on the website, which itself was almost word-for-word the same as this article on Ukrainian website obludatel.od.ua. The original article on obludatel.od.ua, according to a Google search, had only been published two hours earlier.

Similarly, this post, about Ukraine urging the Council of Europe not to support Russia, led to this article on the antifashist.com website, which similarly copied word for word lengthy excerpts, but not the whole text, from this article by Ukrainian newswire Unian.

Not all the articles were pro-Kremlin, although many were. This appears to have been a technique to give the site the appearance of legitimacy by presenting genuine news from other sources as its own.

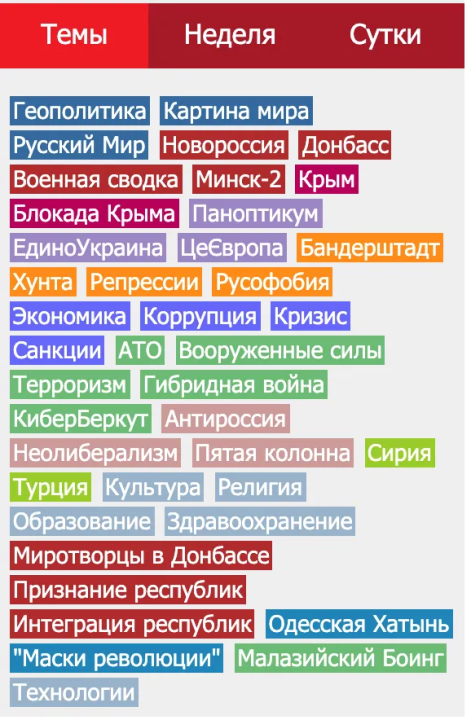

The site called itself an “information agency” and promoted a strongly pro-Kremlin and anti-Ukrainian worldview. For example, tags on its articles included “Novorossiya,” “Donbass,” “Russophobia,” “Repression,” and “Junta” (a term often used by Kremlin propaganda outlets to describe Ukraine’s post-2014 government).

As with infopolk, this website asked for donations, although it did not show the same passion for cryptocurrencies.

A further page, @infocenter.odessa, purported to be a news page in Odessa, Ukraine. Its most recent post was on January 13, 2018, and led to a web story that was a copy of an antifashist.com article. The Facebook page appears to have been a dormant asset, likely identified on the basis of the accounts used to set it up. The website was still actively posting as of May 6, 2019.

The last two pages were less clear in their purpose. One page called “Granch” posted comic memes and had not posted since June 2015. It did not appear to have a strong political angle, and only boasted 13 followers.

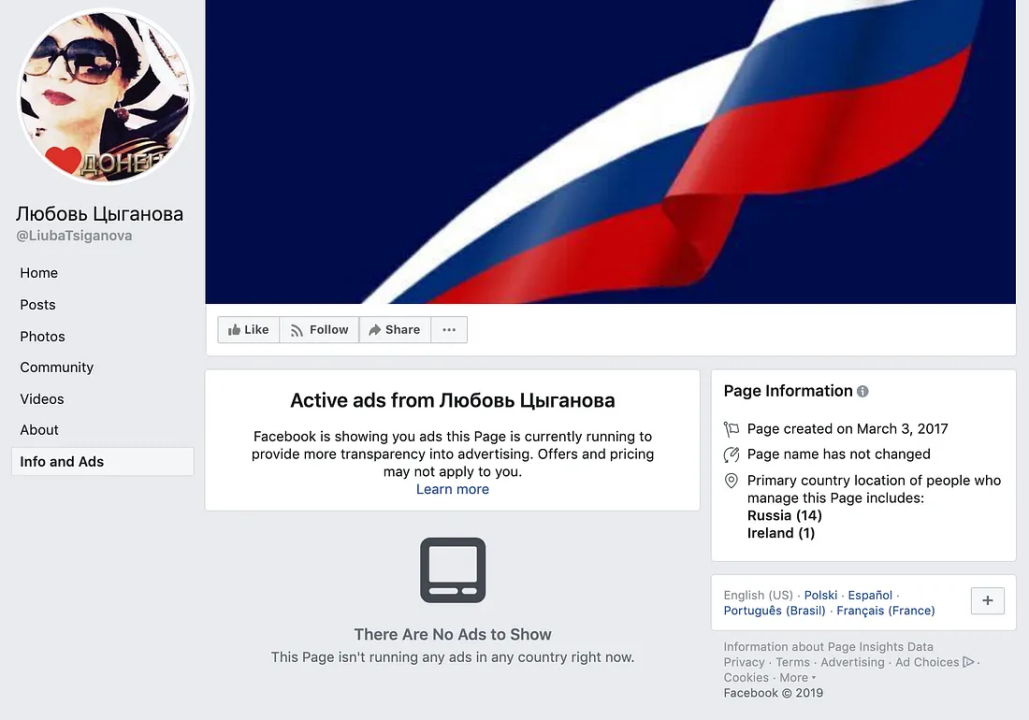

The final page in the set was named Liubov Tsyganova (Любовь Цыганова) and had almost 7,000 followers. It posted a mixture of political content supporting Russia and the separatist entities in Ukraine and seemingly personal content such as stories and photos of visits to Russia. The same name and profile picture also attached to a Twitter account.

While claiming to be a public figure focusing on Ukraine, Liubov Tsyganov was managed by at least 15 people, including 14 in Russia and one in Ireland.

Conclusion

This network appeared, on the surface, to behave similarly to earlier information operations, using social media to amplify Kremlin-run and pro-Kremlin content.

It differed from known Russian state-linked troll operations, however, in the way it used social media to steer users toward websites, rather than trying to engage them on platform. In comparison, the Internet Research Agency (often referred to as the “St. Petersburg Troll Farm”) focused on engaging users on-platform and passing divisive content there.

There are also indications that the network was about money, at least as much as it was about patriotic propaganda. The use of malware, the focus on cryptocurrency, and the offering of games, all suggest that the network was designed to monetize the Kremlin’s patriotic rhetoric, not just simply amplify it. As such, the claim of these pages being an “InfoWar” asset may itself have been disinformation, designed to mask a more prosaic purpose.

Register for the DFRLab’s upcoming 360/OS summit, to be held in London on June 20–21. Join us for two days of interactive sessions and join a growing network of #DigitalSherlocks fighting for facts worldwide!