The Christchurch Call and the Failure of U.S. Leadership

By snubbing historic pledge, the United States retreats from fight against terrorist exploitation of the internet

The Christchurch Call and the Failure of U.S. Leadership

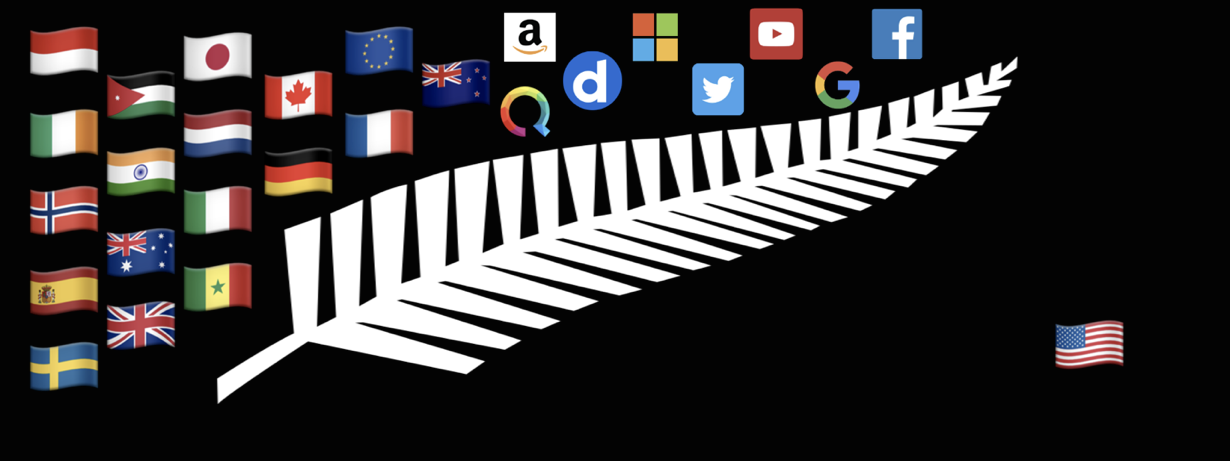

BANNER: (Source: @etbrooking/DFRLab via Wikimedia)

The Christchurch Call, signed by 18 national governments and eight major technology companies on May 15, represents a significant development in the fields of counterterrorism and internet policy. The statement comes two months after a white ethno-nationalist terrorist used a Facebook livestream to broadcast his massacre of 51 worshippers in a Christchurch, New Zealand, mosque. It commits its signatories to explore legal, regulatory, and technical solutions to counter the online spread of terrorist and violent extremist content. The Trump Administration refused to sign, citing unspecified free speech concerns.

The Christchurch Call is a remarkable document for two reasons. First, it stands as the first major multilateral statement jointly signed by both governments and Silicon Valley giants — a historic precedent that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago. Second, the United States’ snubbing of the document represents a retreat from previous counterterrorism pledges. It also reveals a dangerous divide between the White House and U.S. allies regarding the growing threat of white ethno-nationalist extremism.

By signing the Christchurch Call, eight online service providers — among them Facebook, Google, and Twitter — commit to proactive removal of extremist content, a review of the role of algorithms in online radicalization, and the offer of assistance to smaller companies unable to police adequately their own platforms. These are achievable goals: together, the corporate signatories hold sway over roughly 3 billion Internet users.

Although many of the pledged initiatives were already underway (and the document itself is nonbinding), their bold expression here shows how much things have changed. Five years ago, Twitter executives were still debating whether to remove obvious terrorist propaganda. Three years ago, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg still refused to acknowledge that he wielded any political influence at all. By contrast, both Twitter and Facebook used the opportunity of the Christchurch Call to announce new restrictions on livestream technology and the establishment of “crisis protocols” to respond to terrorist attacks in real-time.

Governments, too, have clearly awoken to the dangers of internet-abetted terror attacks. The Christchurch Call is the first document of its sort to be coordinated by a state (in this case, New Zealand) and signed co-equally by government representatives and technology CEOs. It presents a number of policy commitments that have bounced for years around the counterterrorism community. These include public investment in media literacy and counter-extremism campaigns, the creation of industry frameworks for the reporting of terrorist and violent extremist content, and the establishment of close working relations between technology companies and law enforcement.

Together, the governments of these signatory nations — New Zealand, Australia, Indonesia, India, Jordan, and much of Europe — speak for a combined 2.2 billion constituents. It is a sign of the times that, between the two parties, it is the technology companies that represent more people.

Another, more troubling sign can be seen in the United States’ refusal to add its name to the list. Trump Administration officials told The Washington Post that doing so would pose “constitutional concerns.” A White House statement explained that, while it stood “with the international community in condemning terrorist and violent extremist content online,” the United States was “not currently in a position to join the endorsement.”

A close reading of the Christchurch Call does not support the White House’s position. The document avoids any mention of government-mandated speech codes. It emphasizes that any action must abide by “human rights and fundamental freedoms.” The main expectation of governments is that they fight both terrorism and “violent extremism” — as close as the document comes to naming the white ethno-nationalist ideology responsible for the Christchurch attack.

By refusing to sign the Christchurch Call, the United States appears to retreat from previous counterterrorism commitments made under the Trump Administration. In May 2017, the United States joined the Group of Seven (G7) in pledging to “combat the misuse of the internet by terrorists.” The statement outlined government policies virtually identical to those proposed in the Christchurch Call. The only apparent difference is context. In 2017, the terrorists were ISIS militants. In 2019, they are white ethno-nationalists.

Instead of offering support, the United States has dedicated itself to attacking recent counter-extremism measures. Hours after rejecting the Christchurch Call, the Trump Administration announced a “tech bias” initiative targeting Facebook, Google, and Twitter. The intent is to collect “censorship” stories in preparation for potential regulatory action. The clearest impetus for this initiative was Facebook’s prohibition of white nationalist and white identarian speech — a step taken in direct response to the Christchurch attacks, and one which President Donald Trump has railed against on Twitter. “It’s getting worse and worse for Conservatives on social media!” the President wrote.

The surreal result is a counterterrorism document cosigned by U.S. allies and major technology companies — seven of eight of which are headquartered in the United States — and opposed by the U.S. government.

The Christchurch Call represented a historic opportunity for international unity. By seizing this opportunity, technology companies show growing awareness of their political responsibilities. By rebuffing it, the United States shows just how far it has retreated from the fight against terrorism and violent extremism.

This article was co-published with the New Atlanticist blog of the Atlantic Council.

Register for the DFRLab’s upcoming 360/OS summit, to be held in London on June 20–21. Join us for two days of interactive sessions and join a growing network of #DigitalSherlocks fighting for facts worldwide!