Momo’s Back: How an Old Hoax Was Resurrected

Tabloids, Facebook parenting groups, and celebrities fueled viral hysteria in disparate hemispheres

Momo’s Back: How an Old Hoax Was Resurrected

BANNER: (Source: @CerviniFran/archive)

A disturbing internet meme — dubbed the “Momo Challenge” — went viral in February 2019 in the United States and the United Kingdom.

The meme is a cautionary tale in the spread of disturbing false content by well-intentioned adults who try to warn one another about it but end up amplifying it in the process. When the number of actors reaches a critical mass, the desire to inform the public of a perceived threat can veer into viral hysteria, or even moral panic, ultimately being picked up by sensationalist tabloids and, subsequently, mainstream news media.

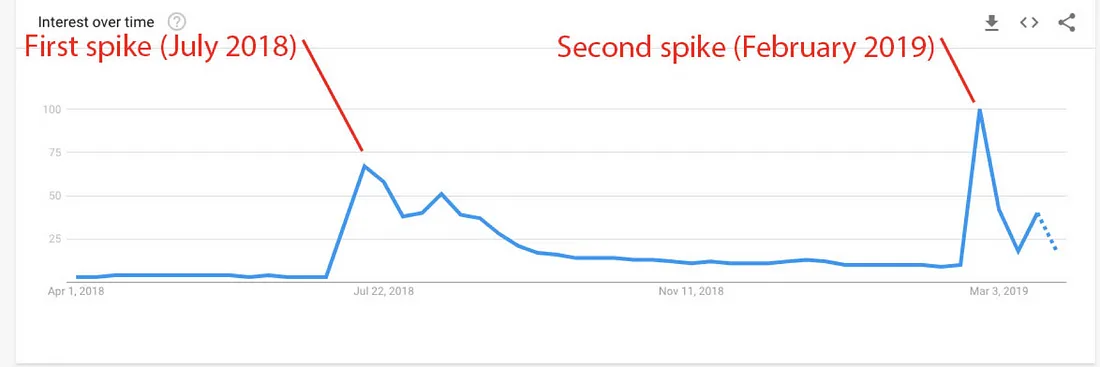

It was not the first time the meme had become an internet sensation. Six months earlier, in July 2018, the challenge had surged in popularity in Latin America and Southeast Asia. The supposed “challenge” allegedly comprised a series of escalating tasks for children to complete, culminating with a participating child’s suicide. No such suicide, or even any other task, has been proven to have been undertaken by a child because of the meme.

As such, this was a case wherein the news media amplified a fear that was not grounded in reality. The “challenge” was largely an urban legend that got turned into a mainstream news story based entirely on the fears of adults.

Disinformation is the proliferation of incorrect information with intentional effort by bad actors, which does not apply in this case, as actors with good intentions unwittingly spread false content and, in doing so, perpetrated misinformation.

Momo Takes Off in Latin America

The fictional “challenge” had several variants. The first version asked people to contact an anonymous WhatsApp number at 3:00 a.m. The anonymous contact would then allegedly reply by claiming that they had personal information about the person, sending disturbing photographs or asking the person to complete a series of “challenges,” culminating in suicide. In other versions, the challenge embedded content in YouTube Kids videos encouraging children to self-harm.

The “Momo” meme originated with a photo in 2018. According to a post by Know Your Meme, on July 10, 2018, a Redditor submitted a photo of a statue created by Japanese artist Keisuka Aisawa in 2016 called “Mother Bird” to the r/creepy subreddit. The post went viral, obtaining approximately 5,300 upvotes and 1,000 comments.

At the time, the photo of Aisawa’s statue was also gaining traction on Twitter and Facebook communities devoted to gaming and paranormal issues. A July 10 tweet by the account @GirlDoesRant, which had just under 4,500 followers at the time of analysis, had a reach of 165,000 users after obtaining 344 retweets, according to Sysomos. Most users reacted by saying they found the picture frightening.

That same day, several phone numbers with Japanese, Colombian, and Mexican area codes started to appear online, especially on Spanish-speaking social media profiles and pages. They were published in a meme format known as “Ten cuidado Sportacus” (Be Careful, Sportacus). There is no explanation online of this meme’s meaning, but several examples show that it employs reverse psychology to encourage individuals to take certain actions, such as calling an anonymous phone number.

When people contacted the anonymous numbers on WhatsApp, the profiles associated with them had Aisawa’s sculpture as their avatar, a detail that has been discussed extensively online, especially on Spanish-speaking media. One of the contacts’ statuses was last updated in June 2018. All of the numbers are currently inactive.

On July 11, 2018, there was a surge of YouTube videos and 4chan threads featuring Aisawa’s doll. These videos and threads used the term the “Momo challenge” to refer to the practice of encouraging internet users to contact the WhatsApp numbers shown above. The origin of the name “Momo” is unclear. Some of the threads were in English, but most were in Spanish. The authors claimed that they had contacted Momo and posted videos of what appeared to be a conversation with the WhatsApp profiles.

Even in the meme’s early stages, some users expressed skepticism. On 4chan, some users mocked those who believed in it and stated that the challenge was fake. In that same vein, a blog post published on a Mexican outlet on July 11 traced the origin of the photo to Aisawa’s sculpture and said that the hoax was “perhaps a sick joke to people or perhaps an attempt to get personal information.”

At that point, the “Momo” meme most closely resembled a “creepypasta” meme (i.e., a scary text or image that is copied and pasted in different online spaces for entertainment purposes). Police officials throughout the Spanish-speaking world labeled the Momo challenge as a security threat. On July 12, 2018, the Informatic Crime Unit (ICU) from the Mexican state of Tabasco posted a tweet saying that contacting the numbers associated with the Momo challenge put users at risk of “exposing personal information,” “incite[d] suicide or violence,” and contributed to an increased risk of anxiety, insomnia, or depression. The ICU, however, did not follow up with any public evidence of anybody being affected by the challenge.

On the other hand, the National Police of Spain also warned that the Momo challenge was a hoax and implored the public to “not believe it.” The police department did not share any evidence to back these claims though.

A week later, on July 25, the Argentinean newspaper Perfil quoted a police source as saying that law enforcement suspected that a 12-year-old girl who had committed suicide had engaged in the Momo challenge. A similar report emerged in Colombia in September, when Colombian police officials said that they suspected the challenge was the catalyst for several teen suicides. In both cases, police officials neither further confirmed nor denied these initial reports, nor did they release any evidence to support the claims.

Momo Returns

The second spike in the Momo meme’s popularity occurred in the last week of February 2019. Unlike the prior spike, this second spike was primarily fueled by media outlets and celebrities publicizing the alleged threat, rather than by new instances of disturbing content associated with the meme appearing online.

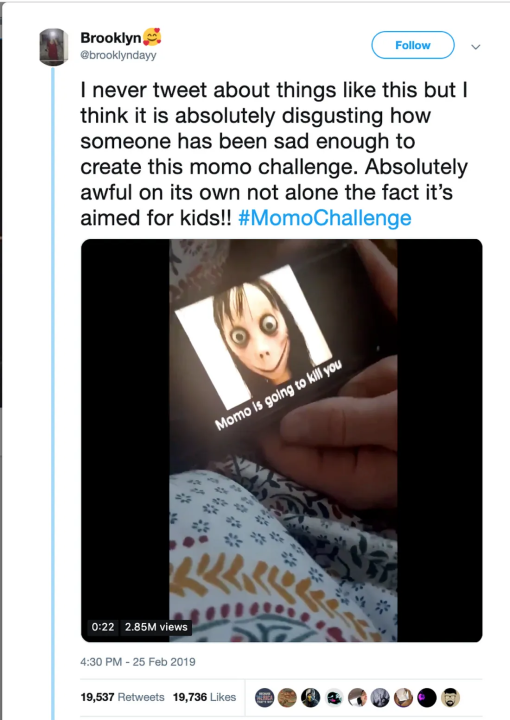

It started with several social media posts warning about videos in which Aisawa’s statue appeared suddenly and disturbingly in Youtube videos aimed at children. One such tweet, posted by the account @brooklyndayy on February 25, had almost 20,000 retweets at the time of analysis.

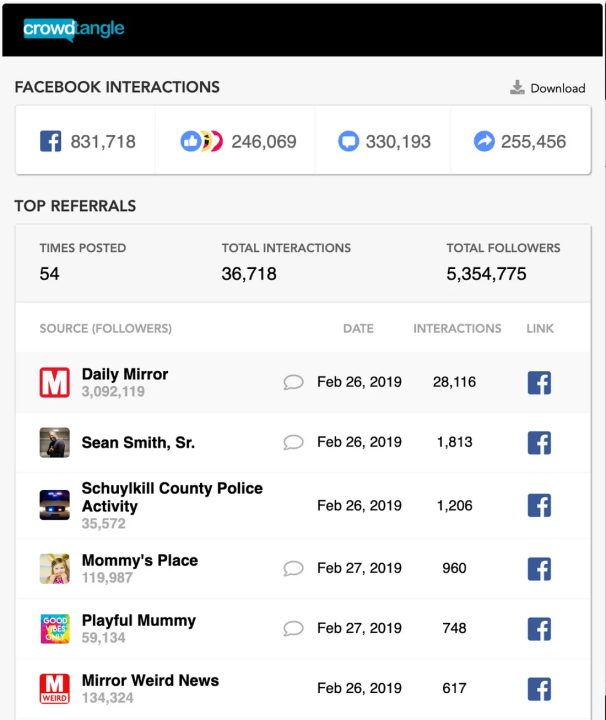

These initial social media posts in turn spurred an increase in the publication of posts on Facebook about the Momo challenge, as well as an increase in Facebook engagements. The most popular Facebook post, according to a BuzzSumo search, was posted by The Daily Mirror’s page on February 27.

The post linked to a piece about a school in the United Kingdom warning students about the “Momo challenge.” The piece had amassed more than 831,000 interactions on Facebook after being shared in different pages and groups. Its biggest amplifiers, other than the newspaper’s social media pages, were the Facebook page of a pastor named Sean Smith, Sr., a Facebook group called Schuylkill County Police Activity, and several parenting groups and pages on Facebook.

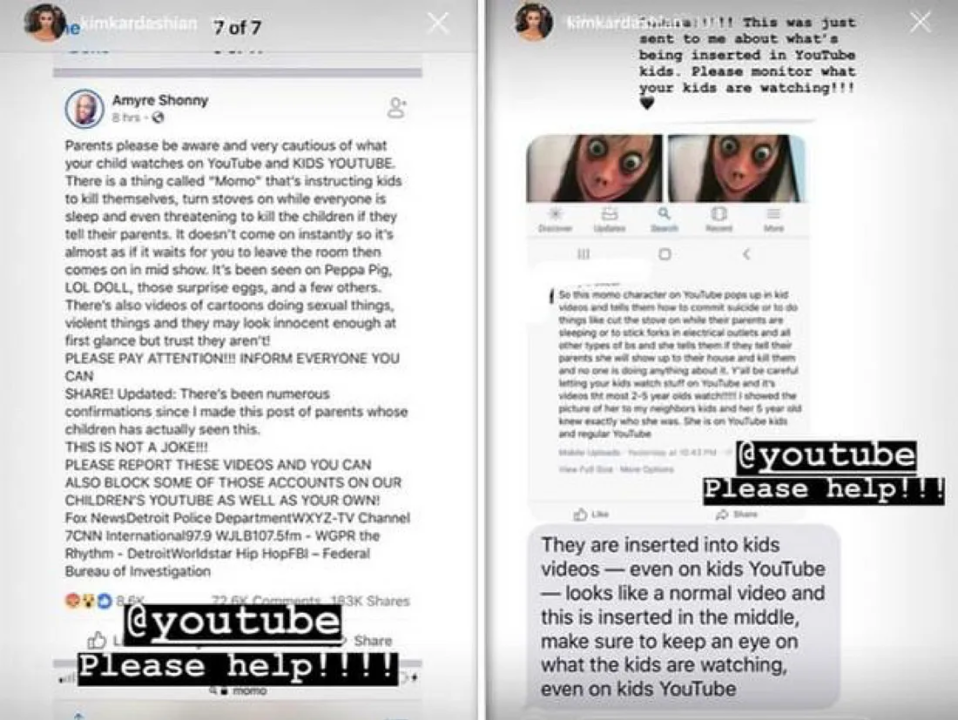

On February 28, Kim Kardashian posted an Instagram story in which she shared a screenshot of a Facebook post (now deleted) by user Amyre Shoony. The post reported some Momo videos that allegedly “instruct kids to kill themselves” and “threaten to kill their children if they tell their parents.” At the time of analysis, Kardashian had 132 million followers on Instagram, and it is unclear how many of them viewed this story. Kardashian’s story prompted a response from YouTube on February 28, which stated that it had “no recent evidence of videos promoting the Momo Challenge” on the platform.

In this news cycle, the media framed the Momo meme as a threat to young children’s safety and wellbeing. For instance, a story in The Daily Mail said that a five-year-old girl had “hacked off her hair after being caught up in the sick Momo challenge online.” A Montana school posted a Facebook post, which local media amplified, stressing that the meme “encourages children to do dangerous and violent acts through social media.” The story was re-published by several British news media outlets as it was distributed by a “human interest story” agency called Hook News Press. In each of these cases, however, the stories were limited to secondhand reporting with no follow-up investigation of the veracity of the claims.

There is no evidence that this scare is based in fact. Neither Kim Kardashian’s Instagram story, nor the footage of the Momo meme posted by @brooklyndayy on Twitter, offered any confirmation that the video was published on YouTube.

Other sources, however, have claimed that the video was once available at this link but has since been removed from the platform. A YouTuber named ItzRooster, for example, included the footage in a video in which he explains the Momo challenge. Also, in a post on the image exchange website Icaut, a user called “crewreadphoto” shared the same link and stated that Momo appears in the video “just after Mummy Pig sees a wasp in the garden whilst having a picnic,” which coincided with the footage posted by ItzRooster.

The footage did not instruct children to commit suicide, and there is no verifiable evidence that other YouTube videos in which Momo appeared did. None of these social media posts and news reports intended to further spread the Momo meme but rather aimed to warn of the perceived risk it posed to child safety. Nonetheless, by posting about the Momo challenge, well-meaning news outlets and social media users contributed to the amplification of the hoax.

In addition, the popularity of the Momo meme among social media users likely further increased media coverage of the meme by incentivizing media outlets to publish more stories on it in an effort to capture online traffic. This case thus stresses the role that media outlets play in the spread of disinformation, owing to incentives from the online advertising industry to spread whatever content generates views, regardless of veracity. It also demonstrates that media and civil society need to develop a framework for discussing and countering mis- and disinformation without exacerbating the problem.

Jose Luis Peñarredonda is a former Digital Research Assistant with the Digital Forensic Research Lab (@DFRLab).

Register for the DFRLab’s upcoming 360/OS summit, to be held in London on June 20–21. Join us for two days of interactive sessions and join a growing network of #DigitalSherlocks fighting for facts worldwide!