Archimedes Ran Politically Charged Facebook Ads in Crisis-Torn Honduras

Israeli firm’s operation, now disrupted by Facebook, supported government and attacked the opposition

Archimedes Ran Politically Charged Facebook Ads in Crisis-Torn Honduras

BANNER: (Source: @luizabandeira/DFRLab)

A portion of the inauthentic assets removed by Facebook on May 16 intended to spread polarizing content in Honduras, a country that has been in the throes of democratic crises for almost a decade and that possesses one of the world’s highest violent crime rates.

On May 16, 2019, Facebook removed more than 265 Facebook and Instagram accounts, Facebook pages, and groups that worked “together to mislead others about who they are or what they are doing” — activity that Facebook refers to as “coordinated inauthentic behavior.” According to Facebook, the pages belonged to a network run by private Israeli firm the Archimedes Group. An analysis conducted by the DFRLab found indications that the pages belonged to the same network and boosted local politicians while disparaging others in locations around the world.

According to Facebook, the Archimedes Group spent $ 812,000 in advertisements in countries in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America between 2012 and 2019. The payment was in three currencies: U.S. dollars, Israeli shekels, and Brazilian reals. The payment in reals indicated that the operation had a focus in Latin America. The main target in Latin America seemed to be Honduras, with a few more assets focusing on Panama and Mexico. There was no indication as to who paid Archimedes to boost content in Honduras nor why the payment was made in reals instead of the local currencies.

In Honduras, the pages ran ads supporting current President Juan Orlando Hernández, who was reelected in 2017 despite fraud allegations, and attacked Manuel Zelaya, a former president ousted by a military coup in 2009. The operation took place within the context of violent protests over health and education reforms in the country.

Democratic Turmoil

Honduras has been dealing with fragile democratic institutions for about a decade. In 2009, a military coup — Central America’s first since the end of the Cold War — ousted left-wing President Manuel Zelaya, an ally of the late President of Venezuela Hugo Chávez. Prior to the coup, Zelaya had declared that he intended to run for a second term, despite the country’s constitutional four-year presidential term limit. Following Zelaya’s ouster, elections were held in 2009, but they too were highly controversial. In 2013, in the first election after the coup in which the opposition ran, right-wing candidate Juan Orlando Hernández was elected.

In 2017, President Hernández was reelected after orchestrating a constitutional maneuver that removed term limits. The election results were highly disputed, as the opposition candidate was leading with some 60 percent of votes counted. Then, after what the electoral court ruled a “computer glitch,” Hernández took the lead and was declared the winner with 42.95 percent of the vote, to the runner-up’s to 41.42 percent. In response, the Organization of American States (OAS) called for new elections and widespread protests took place, led by the opposition candidate and by former President Zelaya, who returned to the country in 2011. Zelaya is currently the president of the main opposition part in the country, Libre.

In April 2019, violent clashes erupted after the Honduran Congress passed two bills to restructure the health and education sectors. Hernández had backed the reforms. His supporters claimed the opposition was fueling the protests in a political move against the president.

In addition to the current political crisis, Honduras is in the midst of a social crisis. The country has the fourth-highest homicide rate in the world, owing at least in part to the activities of the powerful maras, or drug-trafficking gangs. Femicides are also among the highest in the region. Violence, poverty, and lack of economic opportunities, among other factors, have led thousands of Hondurans to try to migrate to the United States. In October 2018, a migrant caravan first formed in Honduras arrived at the Mexico-United States border with about 7,000 migrants from Central America. Since that time, similar caravans have been the modus operandi for escaping the country.

The Influence Operation

The Archimedes Group’s operation tried to exploit these vulnerabilities. Most of the pages targeting Honduras ran pro-government and anti-opposition ads.

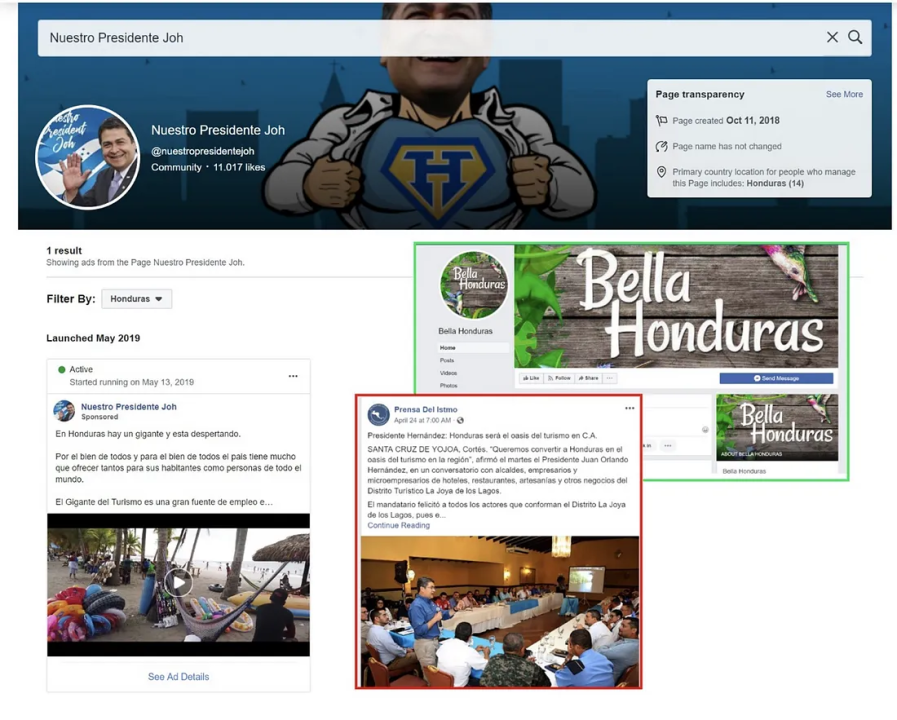

In a tactic similar to those employed in other countries during this operation, some pages masqueraded as news outlets. The page Prensa del Istmo (“Isthmus Press”), for example, presented itself as a news outlet but more closely resembled an official government channel of communication, often uncritically reproducing Hernández’s statements. Created in January 2019, this page had amassed about 14,000 likes in a matter of months.

Prensa del Istmo paid to boost a post related to the health and education reform protests in Honduras. The ad featured a video of Hernández claiming that the Venezuelan government had orchestrated the protests: “Three days ago, there were violent protests in Honduras, but in parallel something was happening in Venezuela [the interim President Juan Guaidó tried to oust Nicolás Maduro on April 30], and it makes you wonder: is it possible that the streets are set on fire in countries from the Lima Group when something happens in Venezuela?”

Honduras is a member of the Lima Group, a multilateral body formed by Latin American countries to address the crisis in Venezuela.

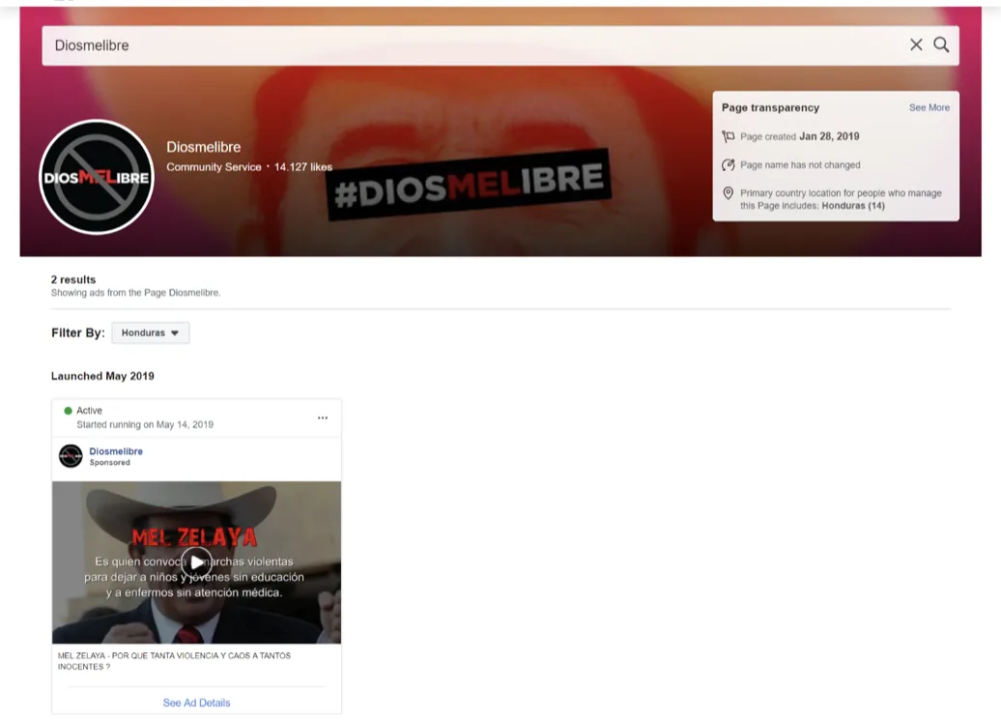

The page Diosmelibre (meaning “God Forbid” in Spanish, and also a play on “Mel,” a nickname for Manuel Zelaya, and “Libre,” the name of his party) also ran ads related to the latest protests. The promoted post featured a video claiming that Zelaya was the one “calling for violent protests to leave children without education and sick people without medical attention.” Much like the Prensa del Istmo page, Diosmelibre was created in January 2019 and had 14,000 likes at the time of its removal by Facebook. Most posts from the page pushed similar anti-Zelaya messages, claiming him to be violent or a source of the violence.

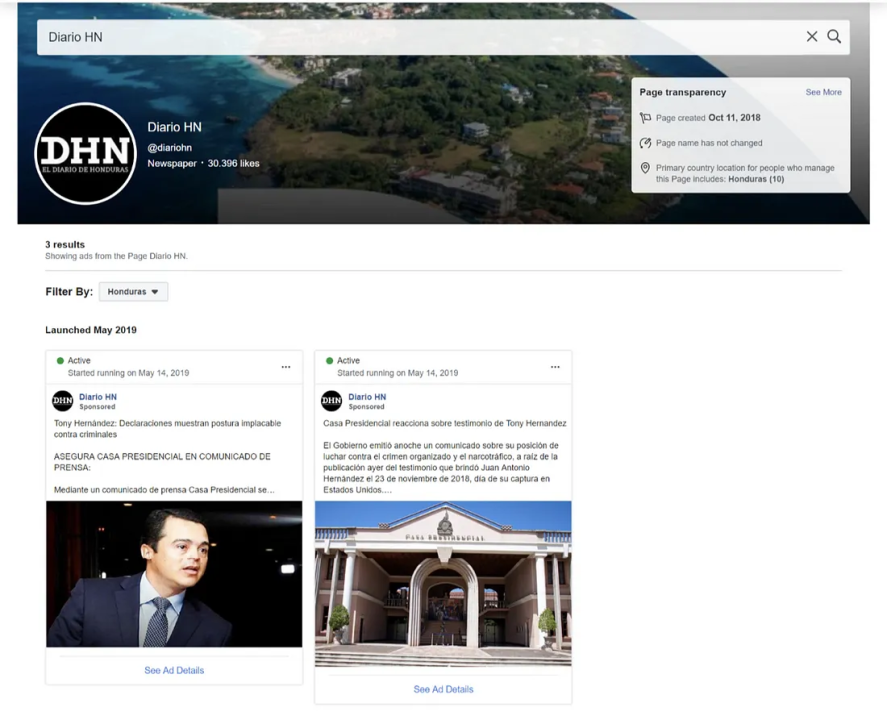

Two pages, Diario NH (“Daily NH”) and La Verdad Desnuda (“The Naked Truth”), promoted the message that Hernández was fighting against organized crime and drug trafficking; one of them referred specifically to the arrest of the president’s brother, Tony, who was accused of dealing drugs. In two sponsored posts, Diario HN, another page that presented itself as a news outlet but acted to spread government propaganda, referred to the imprisonment of Tony Hernández in the United States. The posts promoted the message that the president was so committed to the fight against drug trafficking that he would have arrested his own brother if he were still in Honduras. After his reelection, Hernández had promised to fight drug trafficking in an effort to unite the country.

Finally, some pages seemed allied with the government agenda to promote tourism in the country. The page Nuestro Presidente JOH (“Our President JOH”) boosted a post describing the tourism industry as “a giant that was awakening” and poised to generate jobs in the country. A post on the Prensa del Istmo page had also highlighted Hernández’s plan to develop the tourism industry. In addition, one of the pages taken down by Facebook, Bella Honduras (“Beautiful Honduras”), had also promoted tourism in Honduras.

Conclusion

The Archimedes Group’s inauthentic influence operation in Latin America focused primarily on Honduras. Pages paid to boost polarizing content that seemed designed to widen the gulf between supporters of President Juan Orlando Hernández and supporters of former president Manuel Zelaya, who now directs the main opposition party in the country.

This case study exposed how malicious actors can exploit existing societal vulnerabilities for political purposes. In the Honduran case, the operation not only risked further weakening the Honduran public’s trust in politics and already vulnerable democratic institutions, but it also increased the likelihood that the protests already underway in the country could erupt in violence.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.