A Syrian Soldier’s Life and Death on Instagram

A young man documents his military career on social media — right up until the day militants beheaded him and uploaded it to his Instagram account

A Syrian Soldier’s Life and Death on Instagram

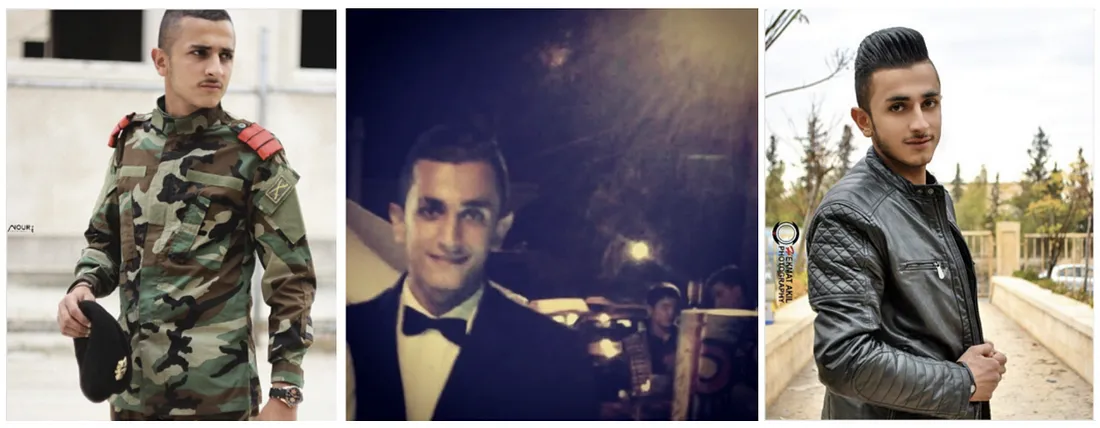

BANNER: Montage of Ibraheem Ahmad Barri’s Instagram account. (Source: ibraheem_ahmad_barri)

While public debate around social media has become dominated by issues regarding free expression, user privacy, the power of tech companies and the like, it’s easy to forget that for most people, it’s just how they go about keeping in touch with the world. On Instagram, for example, millions of people use it as a living scrapbook — a place to document mundane moments and important milestones alike, whether it’s a night out of with friends or a graduation ceremony. For most of those users, it does so indefinitely, an ongoing capturing of all things present, with little sense of what might be worth featuring in the future. Such was the case for one Syrian soldier, documenting the mundane and the milestones on his Instagram feed — until the day the militants who captured him and his phone uploaded a photo of his decapitated head to his account.

This isn’t the story of the good guys versus the bad guys in Syria. History will judge the Assad regime harshly for its innumerable war crimes and strategic cruelty toward its own populace, as will it judge the barbarity of militants who mock the rules of war through executions of captives.

Instead, this is the story of an Instagram account, and the life it documented over a series of 45 photos.

The story begins with another death.

Ibraheem Ahmad Barri uploads his first Instagram post on November 4, 2016. It shows the picture of a smiling boy with aviator sunglasses. “May God bless you,” Ibraheem writes as a caption. It doesn’t appear to be Ibraheem, but someone close to him, as he uploads two more posts about the boy over the course of the month.

In one of these photos he quotes a song by Iraqi musician Saif Amer and poet Ali Alferdawy: “I remember your laughter and I cry…and I tell my tears not to fall.” In yet another post, a montage of the boy’s photos, Ibraheem writes “October 27, 2016,” followed by a sad emoji. By all signs, the boy has recently passed away, and it would seem that his death motivates Ibraheem to begin using Instagram as a way to memorialize him.

During the next six months, Ibraheem posts a series of images of himself in civilian and military dress. In some photos, he’s sporting a tuxedo, a leather jacket, an oxford shirt; in others, a camouflage uniform and beret. In all of his uploads, he exudes confidence.

Ibraheem sporadically posts more photos of himself over the next two years, mostly appearing on his own or with friends, family, and military buddies. In July 2018, we see him learning how to shoot a rocket propelled grenade launcher. In a comment he writes:

[Achieving] Canadian citizenship may be difficult …

European citizenship may be more difficult …

The U.S. may be the most difficult …

But there is one nationality impossible [to achieve]…

Is the nationality that gives its owner the title of masculinity and heroism …

It is the title of honor…

Syrian Arab nationality.

Ibraheem is proud to be a Syrian soldier. Nearly half of his photos show him wearing army fatigues or some other military uniform. He also posts a photo of President Bashar al Assad and his father Hafez al Assad — who ruled with an iron hand before him — along with a comment about loyalty. Here is a young man sure of his role in life, as a soldier and a Syrian. His Instagram posts give no hint as to whether he ever saw or participated the other side of the war: the atrocities, the destruction, the war crimes against civilians that his compatriots engaged in, all in the name of preserving Assad’s regime.

The last time Ibraheem is seen alive on his Instagram was July 1, 2019. He’s sitting in the lobby bar of the Sheraton Aleppo Hotel, wearing an untucked checkered shirt, an oversized watch on his left hand. Though he’s alone in the photo, he’s clearly with company: the table in front of him is jammed with coffee cups and water glasses in various stages of emptiness, plus a couple of packs of cigarettes. As it turns out, he’s with family — another young man and a boy who appears to be a teenager. They’re not in the photo, but because they’re also on Instagram, we can picture the scene more clearly. Their names are Mohamed Ahmad Barri and Mahmoud Barri.

For the next week, Ibraheem’s Instagram remains quiet. Then on July 9, 2019, someone uploads a horrifying image to the account. The graphic photo shows Ibraheem’s severed head placed atop a camouflage backpack. Two men’s feet can be seen with their shoes contemptuously holding the head in place, while a third foot — perhaps Ibraheem’s or a fellow soldier’s — juts awkwardly from outside the bottom left frame. (Given its graphic nature, we’ve chosen not to republish the photo here. Vicarious trauma from viewing graphic imagery is a serious issue, as I wrote about last March.) Who exactly uploaded the photo remains unclear, but their decision to post it to Ibraheem’s Instagram serves as a final reminder that they were in complete control of his grisly fate at the very end.

The photo is posted without comment by the person who uploaded it, but it’s quickly followed by hundreds of responses: many in anger, many more offering prayers, and a smattering of insults mocking him. For Ibraheem, it would be the last known photo taken of him, but it wouldn’t be the last posted to the internet. In the days following his death, family members like Mohamed and Mahmoud Barri used social media to mourn their loss and present him as a hero. Mohamed posted two photos to his Instagram account: an image of Ibraheem in front of a Syrian flag overlaid with a stylized camouflage filter with text describing him as a martyr and a hero, and a second image of a street protest with two men holding large posters of Ibraheem when he was alive, including a photo taken from his Instagram. Mahmoud, meanwhile, reposts a photo he had taken together with Ibraheem in late June, just weeks before his death.

He approaches a sandbag enclosure and climbs atop it. He quotes the Quran— Ayah al-Anfal 8:17 — which roughly translates to, “It was not you, oh Muslim believers, who slew the enemy, it was Allah.”

Then, someone says, “We are going to shoot.”

He fires the RPG at the enemy position.