Libyan Hashtag Campaign Has Broader Designs: Trolling Qatar

Organized Twitter campaign supporting Haftar advocated the regional political interests of the UAE

Libyan Hashtag Campaign Has Broader Designs: Trolling Qatar

BANNER: (Source: Twitter)

This is the second article of a two-part series on a hashtag campaign supporting Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar during his campaign to take Tripoli. Part 1 can be found here.

A network of more than 100 Twitter accounts exhibited inauthentic coordinated behavior by encouraging public support for Libyan General Khalifa Haftar and his self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA) while simultaneously criticizing Qatar and promoting the interests of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) — though its impact appears to have been modest.

Though many of the accounts were created in parallel with Haftar launching his offensive against the United Nations-backed Libyan government in Tripoli on April 4, 2019, some of the accounts involved in the UAE-Qatar rivalry date back as far as 2015. The DFRLab cannot attribute the coordinated campaign to a particular entity, but the overall pro-UAE/anti-Qatar narrative suggests it is being managed by someone or something supporting the UAE’s interests around the world.

A Network of Pro-Haftar Tweets Emerges

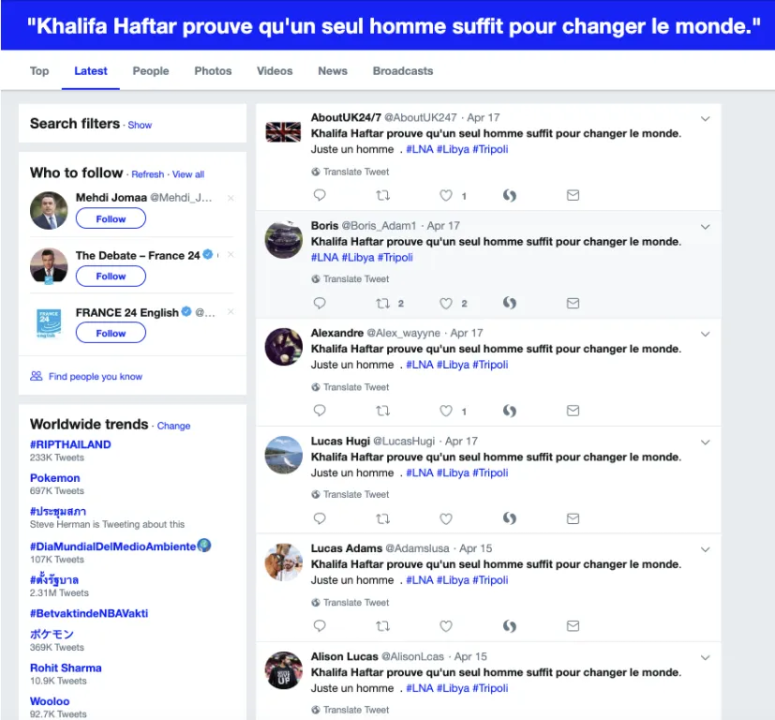

The DFRLab first became aware of a possible organized Twitter campaign when journalist Jihâd Gillon of Jeune Afrique noticed an emerging pattern of new Twitter accounts repeating pro-Haftar rhetoric verbatim in April 2019. Gillon saw tweets in French with the same refrain: “Khalifa Haftar prouve qu’un seul homme suffit pour changer le monde. Juste un homme. #LNA #Libya #Tripoli” (“Khalifa Haftar proves that it only takes just one man to change the world. Just one man.”) Gillon noted on Twitter on April 10, translated from the original French, “Since yesterday, this almost word-for-word message has been relayed by recent French accounts with zero or few subscribers.”

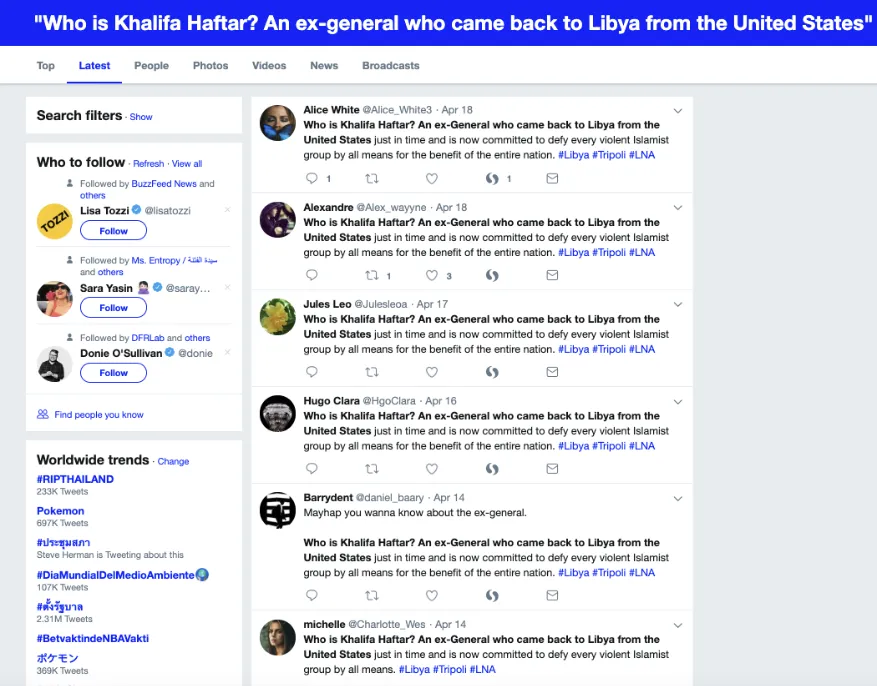

Gillon uncovered a number of verbatim pro-Haftar tweets written in both French and English, with account names and biographies giving the initial impression that the accounts were based mostly in the United Kingdom and France. They appeared to be part of an operation generating inauthentic accounts to support Haftar’s Tripoli campaign.

The DFRLab decided to pick up on Gillon’s reporting and mapped out the scope of the Twitter campaign to see if it had broader political goals. Ultimately, we identified more than 110 Twitter accounts exhibiting coordinated inauthentic behavior, including at least 90 accounts that are still active at the time of writing. Perhaps most interestingly, the coordinated effort went beyond supporting Haftar’s campaign, as it became clear it was actively promoting the interests of the UAE more broadly, launching systematic political attacks against its regional rivals, Qatar and Turkey.

The Network’s Origins

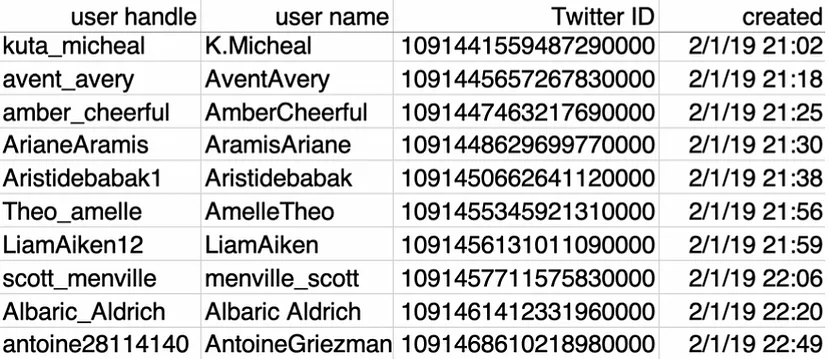

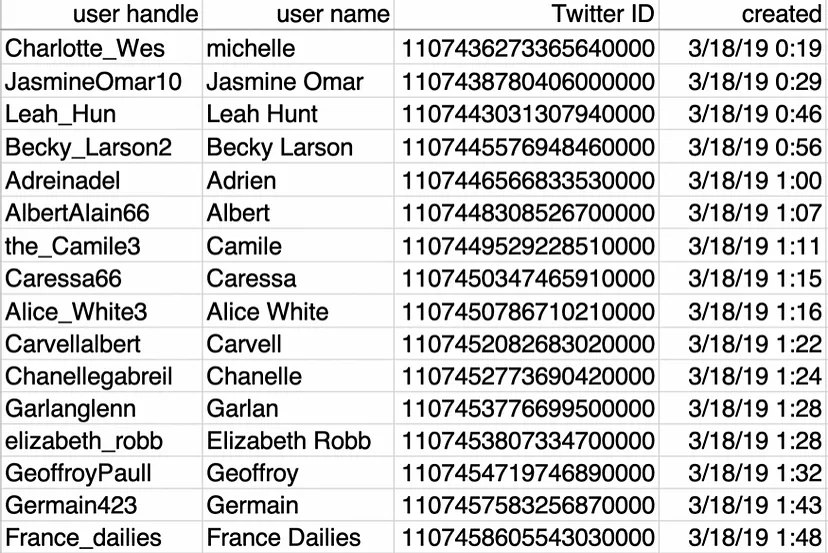

According to metadata from Twitter and open-source analysis tool Tweetbeaver, the earliest Twitter accounts associated with the inauthentic network emerged in 2015, with at least 32 of them being created that year. The network expanded slowly over the next three years until it hit a growth spurt in December 2018, creating at least 50 more accounts over a period of five months. For example, over the course of two hours on February 1, 2019, 10 additional accounts were generated.

A similar burst occurred on March 18, 2019, approximately two weeks prior to Haftar’s Tripoli campaign, in which 16 new accounts were created within 90 minutes of each other.

Haftar’s Inauthentic Twitter Fan Club

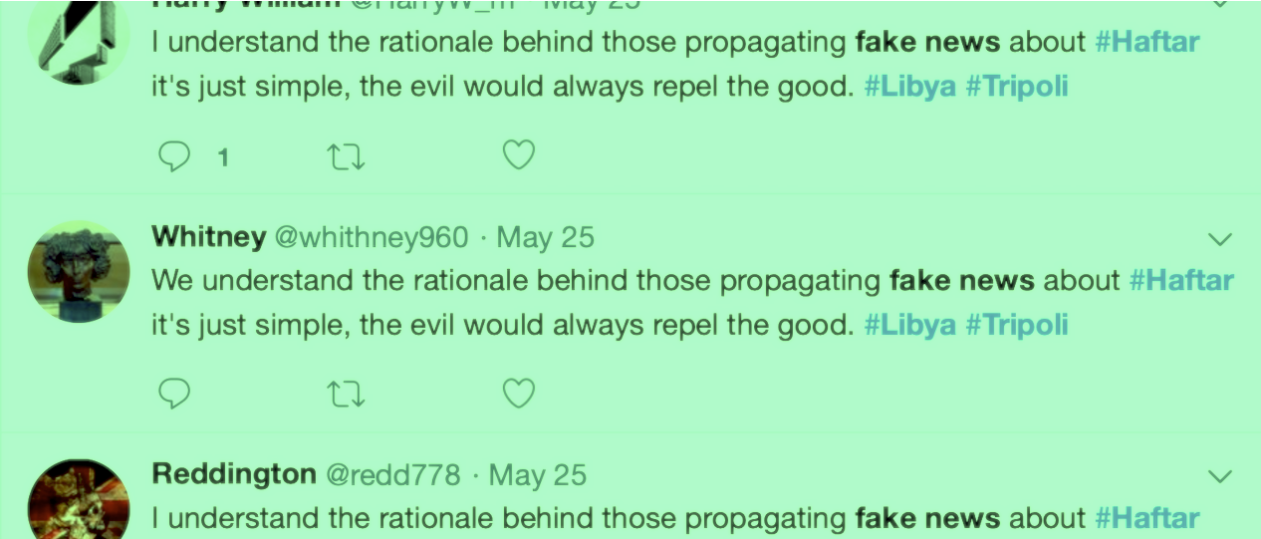

In the weeks and months following Haftar’s initial assault on Tripoli, the coordinated operation kicked into action. Nestled between mundane tweets about soccer, Game of Thrones, sports cars, and Kim Kardashian could be found verbatim jingoistic tweets singing the praises of Haftar and his self-styled Libyan National Army. The tweets were almost exclusively in French or English, usually distributed across a dozen or so separate accounts with different combinations of accounts used for each post. Some examples of these coordinated tweets:

Khalifa Haftar is now more influential in Libya than the so-called ‘Peace brokers’. Posterity will add credence to this statement. #LNA #Tripoli #Libya (tweeted 20 separate times)

Khalifa Haftar prouve qu’un seul homme suffit pour changer le monde. Juste un homme #LNA #Libya #Tripoli (tweeted 27 separate times)

Despite the heinous impacts of Al Sarraj and several terrorist groups, Libya haven’t budged thanks to the likes of Khalifa Haftar. Arise Libya! #LNA #Libya #Tripoli (tweeted 17 separate times)

Fayez al-Sarraj and Qatari-supported terrorist groups are taking concerted efforts to discredit Khalifa Haftar. Its understandable, bad always tries to smear the good. #LNA #Libya #Tripoli (tweeted 19 separate times)

To reiterate, these tweets were not posted verbatim by the same one or two dozen accounts again and again. Instead, they were posted across a varying subset of the more than 90 accounts that the DFRLab identified as being a part of the coordinated operation, with a different combination of accounts utilized each time. This technique potentially helped the accounts avoid detection by Twitter’s spam filters.

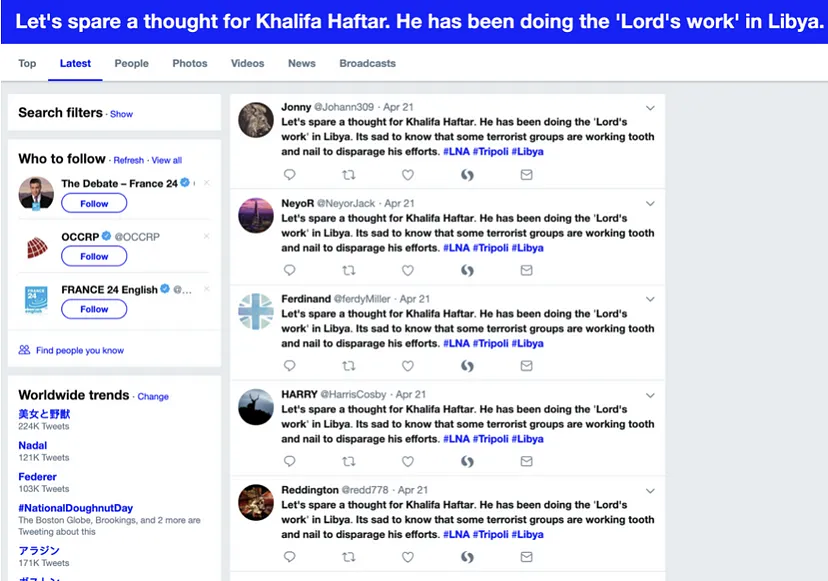

As the assault on Tripoli continued, these accounts posted the same verbatim tweets, utilizing hashtags often used by news organizations and the general public following Libya closely, including #Haftar, #Libya, #LNA, and #Tripoli. One example encouraged sympathy for Haftar’s efforts while criticizing what they referred to as “terrorist groups” — a term often used by Haftar supporters to disparage the Muslim Brotherhood, an enemy of the UAE that has been historically supported by both Qatar and Turkey. While variants of the tweet appeared nearly 20 times over the course of two weeks, at least five of them were posted over an 11-minute period on April 21.

Taken together, the DFRLab counted 687 references to Haftar across the more than 90 accounts active at the time of writing. It is likely the number would be higher if Twitter had not already suspended other accounts involved in the network. Digging into the Twitter timelines further, though, it becomes clear that the network of Twitter accounts have a much broader strategy beyond supporting a military campaign in Libya: to promote the interests of the UAE while undermining Qatar and Turkey.

Criticizing Qatar

To analyze the narratives promoted by the Twitter network, the DFRLab downloaded the Twitter archives of the accounts still active at the time of writing and searched for narrative patterns. As noted earlier, the accounts covered a range of non-political topics: for example, there were 446 references to soccer and an additional 246 references to Lionel Messi. Surpassing any other topic, though, were tweets referencing Qatar (1,351 occurrences) and the UAE (490 occurrences), with overwhelmingly negative messaging directed at the former and supportive posts for the latter.

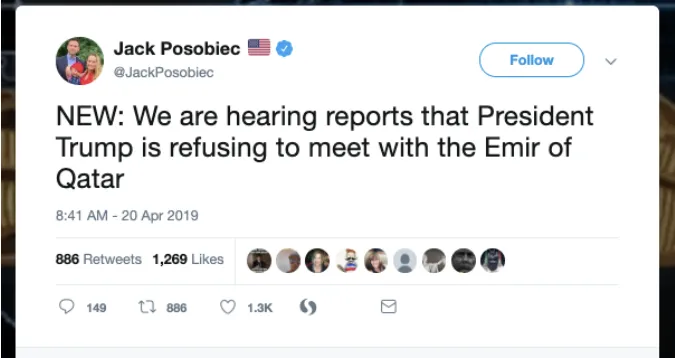

The tweet that received the most retweets from the network came from alt-right conspiracy theorist Jack Posobiec, referring to President Trump snubbing the Emir of Qatar. It was retweeted 66 times by the operation.

Other posts retweeted by the operation expressed anti-Qatar viewpoints, including criticism of their hosting of the next FIFA World Cup. One tweet, an essay critical of Qatar from the EU Observer, was retweeted 43 times by the operation, while another from former Margaret Thatcher aide Nile Gardner regarding secret payments from Qatar to FIFA was retweeted 40 times.

The coordinated tweeting against Qatar did not stop there. Among the retweets were ones amplifying an account called Human Rights Qatar (@HRQ_Qatar). One of this account’s tweets criticizing Qatar’s treatment of workers in the leadup to the World Cup was retweeted 38 times by the network. “You can’t underpay workers, deprive them of rights such as casual leave and consequently not expect a backlash such as this,” the tweet read. “#Qatar have opened Pandora’s box, behold Qatar and be incarcerated into stone. Let’s guard our eyes. #FIFAWorldCup”

The retweeting of @HRQ_Qatar is particularly notable. The account, created in January 2015, focuses almost exclusively on discussing human rights abuses in Qatar. Among the more than 48,000 tweets from the operation reviewed by DFRLab, a total of 848 of them were retweets of @HRQ_Qatar. A similar pattern emerged among tweets favorited by the operation’s Twitter accounts: out of more than 11,000 tweets favorited by the operation, 687 of them were of tweets authored by @HRQ_Qatar.

At the time of writing, @HRQ_Qatar had 233 followers on Twitter, of which more than 10 percent of them (24 in total) were involved in the operation. And among the first 20 accounts to follow @HRQ_Qatar, 10 of them were involved in it.

A similar pattern can be found in another anti-Qatar account, @FreeFromTerror. Founded in October 2015, @FreeFromTerror was retweeted by the network at least 692 times and favorited at least 554 times. Meanwhile, nine of its first 20 followers were operation accounts — as was the account @HRQ_Qatar.

Showing Support for the UAE

While much of the operation focused on lambasting Qatar, it also took advantage of opportunities to amplify pro-UAE tweets highlighting its positive role in the region and the world at large. For example, a tweet from the Nigerian account @exploringnaija praising the UAE Embassy’s support of rural medical care in the country was retweeted a total of 40 times, with 35 of the tweets coming from accounts affiliated with the operation. Similarly, 18 of the tweet’s 23 likes were operation-affiliated.

Meanwhile, a tweet from the Dubai Media Office (@DXBMediaOffice) promoting the UAE’s solar farms received 30 of its 58 retweets from the operation’s accounts.

The Twitter network did more than amplify pro-UAE tweets. It would also go on the offensive when other Twitter users criticized the country. One of the most notable examples occurred when Human Rights Watch Executive Director Ken Roth called out the UAE’s “hypocrisy” as “one of the world’s fiercest enemies of free speech.” The Twitter network quickly mobilized to post replies to Roth. “[T]his is more of same shit everyday,” one wrote. “Same write up everywhere. Defaming a single place #UAE. Rethink and re-compose.” “[W]hat’s more of hypocrisy than what u just did?” added another. “U obviously seem to have been paid for this. #UAE not in this.” “This kind of talk against the UAE is just people trying to promote propaganda,” added a third.

Who’s the Perpetrator?

While the Twitter accounts participating in the coordinated effort espoused pro-UAE and anti-Qatar views, there was no way to ascribe the entity behind the effort. And while the repetitive, verbatim nature of many of the tweets suggested certain bot-like behaviors, it is also strongly possible that the accounts are run by actual people in a coordinated fashion. The size and scale of the operation — approximately 100 accounts publishing tens of thousands of tweets — could easily be accomplished without automation if a group of people were committed enough to perpetrate it. No matter the exact entity behind it or their methods, though, the overall narrative of the operation made it clear that it was attempting to amplify messaging in support of the UAE and its various interests while denigrating its rivals, with Qatar a particularly favorite target.

Mohamed Kassab is a Research Assistant with @DFRLab and is based in Egypt.