How Not to Vote: Inaccurate Voting Instructions in India

Viral WhatsApp message prior to Indian elections provided local social media users incorrect voting instructions

How Not to Vote: Inaccurate Voting Instructions in India

Viral WhatsApp message prior to Indian elections provided local social media users incorrect voting instructions

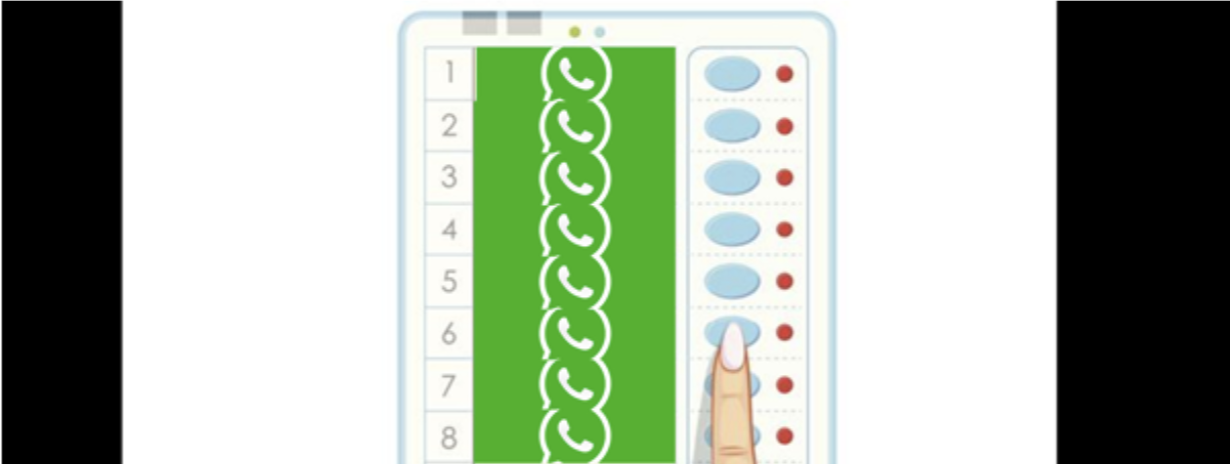

In the lead up to the general elections in India, held in April, incorrect information on how to cast a ballot spread widely across social media. Users on a number of social media platforms, especially WhatsApp, disseminated the content, either by replicating the text of what appeared to be a screenshot of a WhatsApp conversation or by posting the screenshot directly.

(The problematic text is referred to as “the post” for the remainder of this report.)

The DFRLab previously highlighted the high volume of mis- and disinformation shared over the course of the Indian election. While content involving doctored photos and videos attempted to manipulate social media users’ political preferences, the post in this report was particularly harmful because it focused on the process of voting itself in a nonpartisan way, as opposed to attempting to shape the political preferences of voters. This type of false information has the potential to undermine the results of an election directly.

The post was apolitical in nature, insofar as it contained no party identifiers, thus making both followers of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the opposition Indian National Congress (INC) susceptible. The DFRLab was unable to determine the original source of the false information, and it is unclear whether it was merely a case of misinformation, wherein the author sought to provide good advice but ended up propagating incorrect information, or malicious targeting of prospective voters intending to mislead them. Regardless of its nonpartisan appearance, the viral post spread three pieces of guidance about the voting process, two of which were incorrect. If the guidance was followed by any voter, it would have led to their vote being invalidated.

Specifically, the post provided Indian social media users instructions on what to do in the event that their name was not on the electoral register, if they found someone had already cast a vote in their name, or if multiple individuals had impersonated them at the polling booth and cast a vote in their name.

The Post

The post was comparatively unsophisticated in comparison to other cases of false content the DFRLab examined over the course of the Indian elections. In this case, it consisted solely of a body of text furthering the three pieces of guidance, often appearing as, what looked like, a screenshot of a WhatsApp conversation.

Though the screenshot appears to be from WhatsApp, as mentioned, it is unknown as to whether the spread of the screenshot and the information itself started on WhatsApp.

Discerning users could independently and relatively easily verify whether the information it contained was accurate. BOOM Factcheck, a local fact-checking outlet, identified the inaccurate content as early as April 4, just days ahead of the start of the first phase of the Indian elections on April 11.

While the number of Indian citizens who had their vote invalidated after following the erroneous instructions cannot be ascertained, the fact that the post was so widely amplified demonstrates the ease of spreading false information in the Indian information environment and has implications for democracies around the world.

Spreading the Incorrect Information to Social Media

WhatsApp, an encrypted platform with the capability to disseminate information quickly and at scale, is notoriously hard to analyze in terms of spread of potentially harmful content, as in this case.

Encryption, while allowing protection from government overreach among other things, also means that access to the content is similarly restricted to what makes it out into public via other means. The ease by which messages are broadcast, as it is relatively simple to distribute a message to a number of users quickly and with a greater level of built-in trust, presents a separate but just as critical problem. WhatsApp messages can have outsize influence as the platform is often used as a primary communication vector connect with friends and families. In January 2019, WhatsApp took steps to limit the capabilities that enabled the widespread dissemination of mis- and disinformation around the 2018 Brazilian election.

As such, the impact and reach of the post on WhatsApp cannot be measured. Besides the shares via WhatsApp, however, Indian social media users subsequently shared the post on Facebook and Twitter, among others.

Similarly, when high-reach (i.e., “popular”) accounts amplify bad information, it can act as an accelerant for a small flame of false content.

Madhu Kishwar, an Indian professor and the founder of local human rights nonprofit MANUSHI, also inadvertently amplified the misleading content in a thread on her verified Twitter account.

At the time of the tweet, @madhukishwar had more than 2 million followers on Twitter. Sysomos analysis shows that the account continued to accrue a steady stream of followers in the days leading up to and following its sharing of the misleading content. The account’s high follower count demonstrates that it had the potential to be a particularly robust amplifier of the false claims furthered in the post.

Reflecting the viral nature of this particular piece of misinformation, @DrSYQuraishi, the verified Twitter account belonging to former Election Commissioner of India S.Y. Quraishi, tweeted a clarification in response to SM‑Hoaxslayer, another local fact-checking outlet, regarding the claims in the original post.

At the time of analysis, @madhukishwar’s tweet had received 2,900 retweets and 4,100 likes, in comparison to @DrSYQuraishi’s tweet correcting the bad information, which had only received 368 retweets and 470 likes. This discrepancy points to the difficulty gaining traction that fact checkers often face when debunking mis- and disinformation.

While the DFRLab was unable to confirm whether the post had indeed originated on Whatsapp, this analysis sought to incorporate other forms of evidence in order to ascertain the virality and reach of this piece of misinformation. In particular, the incorrect information was amplified by users across a range of other platforms that do provide some form of public engagement metrics. The results of this broader analysis showed that the post likely had significant reach and therefore a worrying and possibly tangible impact, given that it was shared ahead of the first phase of polling, a time when most users would be on the lookout for information pertaining to the elections.

With more than 300 million regular users of WhatsApp in India, international media outlet The Financial Times dubbed the recently elections as the first “WhatsApp elections” in the country’s history. In this regard, while the growing number of Indians on social media platforms has enabled a greater degree of interconnectedness and a step forward in the digital literacy of India’s diverse population, the sharp increase in the userbase has also made citizens increasingly vulnerable to false content and propaganda shared on social media.

Follow along on Twitter for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.