The Kremlin’s search for scapegoats amid Moscow protests

To discredit the pro-democracy protests gripping Moscow, the Kremlin claimed they were an outside job

The Kremlin’s search for scapegoats amid Moscow protests

BANNER: (Sources: Depositphotos/archive, left; Deutsche Welle/archive top right; 12RF/archive, bottom right.)

In response to the mounting pressure from the Moscow protests, Kremlin authorities have doubled down on unsubstantiated accusations of foreign interference in Russia’s domestic affairs.

On August 19, 2019, the State Duma announced the creation of an inter-factional commission to investigate foreign interference in the domestic affairs of the Russian Federation. Even though all four Duma factions — United Russia, the Communist Party, the Liberal Democratic Party, and Fair Russia — supported the initiative, authorities lacked substantial evidence to accuse the United States and Germany in meddling in Russia’s domestic affairs.

The chairman of the State Duma’s lower chamber, Viacheslav Volodin, outlined the rationale for establishing the committee: “We see how state channels of a number of countries voice statements such as, ‘Get up, Moscow!’, summons, indications of [protest] gathering places. All of this confirms interference in the affairs of the Russian Federation. We cannot allow this. That is why it was decided to create a State Duma Commission.”

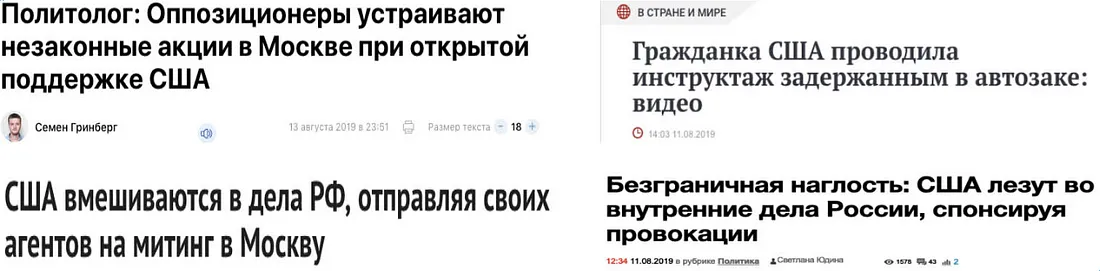

The commission arises, perhaps, as a real world manifestation of the Kremlin’s proclivity for distraction and appeals to hypocrisy. The DFRLab previously examined how pro-Kremlin media pushed false claims that the U.S. Embassy in Russia had incited, and even orchestrated, the protests. In addition to reinforcing this narrative, the Kremlin introduced two new narratives: the first alleged that German newspaper Deutche Welle (DW) incited people via social media to join the protests; the second claimed that the United States had planted covert agents among the protesters to aid them in dealing with law enforcement. These claims of foreign interference had no basis in fact; but the Kremlin nonetheless used them to discredit the protests and justify its harsh crackdown on the protesters.

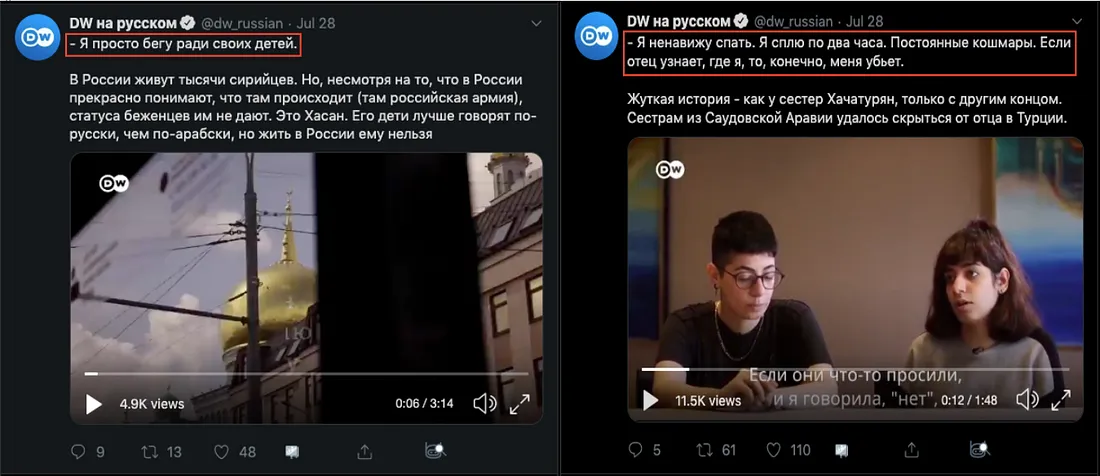

Deutsche Welle did not incite the protests

DW, the German public international broadcaster, has come under criticism from pro-Kremlin authorities for its coverage of the protests. Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) spokeswoman Maria Zakharova explicitly accused the German outlet of interfering in Russia’s affairs.

On July 27, DW’s Russian service posted a tweet that included a video of protesters marching in Moscow. The video was accompanied by the quote, “Moscow, come out!”

Russian authorities interpreted the tweet as an incitement to protest. Later that same day, shortly after the tweet appeared, Russian riot police briefly detained DW journalist Sergey Dik while he was covering a violent crackdown by the police at an opposition rally.

– Москва, выходи!

Нет, еще, похоже, ничего не закончилось. А полицейский специально толкнул нашего корреспондента плечом во время съемки (тот успел сгруппироваться) pic.twitter.com/BCqC3Y10dw

— DW на русском (@dw_russian) July 27, 2019

The DW tweet in question, however, did not call for people to join the protests; it simply quoted the protesters’ chants. Throughout the 23-second long video, the protesters can be heard chanting: “Moscow, come out!” The accompanying text in the tweet started with a hyphen, which in Russian may be used to indicate a quote as an alternative to using quotation marks. DW’s Russian service has used this convention in other instances to indicate direct speech, indicating that it may just be the outlet’s in-house style.

The DFRLab examined all of the DW Russian service’s tweets and Facebook posts published between July 25 to August 4 but found none that incited people to protest. Russian authorities’ claim that DW had posted content encouraging people to attend protests appears to be unsubstantiated. DW denied that any of its posts had urged people to join the protests and instead claimed, on August 5, that the accusations were related to Dik’s arrest.

When DW wrote an official protest to Russia’s MFA for the detention of its accredited journalist, however, the MFA responded that, since “DW unequivocally called for mass participation in an illegal rally […] considering this circumstance, [its] employees could not be considered journalists, as they had become active participants in illegal activities” and, as such, were not entitled to enjoy the privileges and freedoms afforded to members of the press. Instead of presenting evidence that Dik committed a criminal offense during the protests, however, the MFA linked his detention to the tweet published by DW earlier on the same day.

On September 4, a Russian parliamentary committee invited DW representatives to the State Duma to respond to the above-mentioned allegations about interference. DW declined the invitation, however, saying that company is a subject of public law of the Federal Republic of Germany and therefore accountable to the German supervisory authorities only. After DW refused to attend, Russian authorities threatened it to revoke the outlet’s accreditation in Russia.

The United States did not plant agents among the protesters

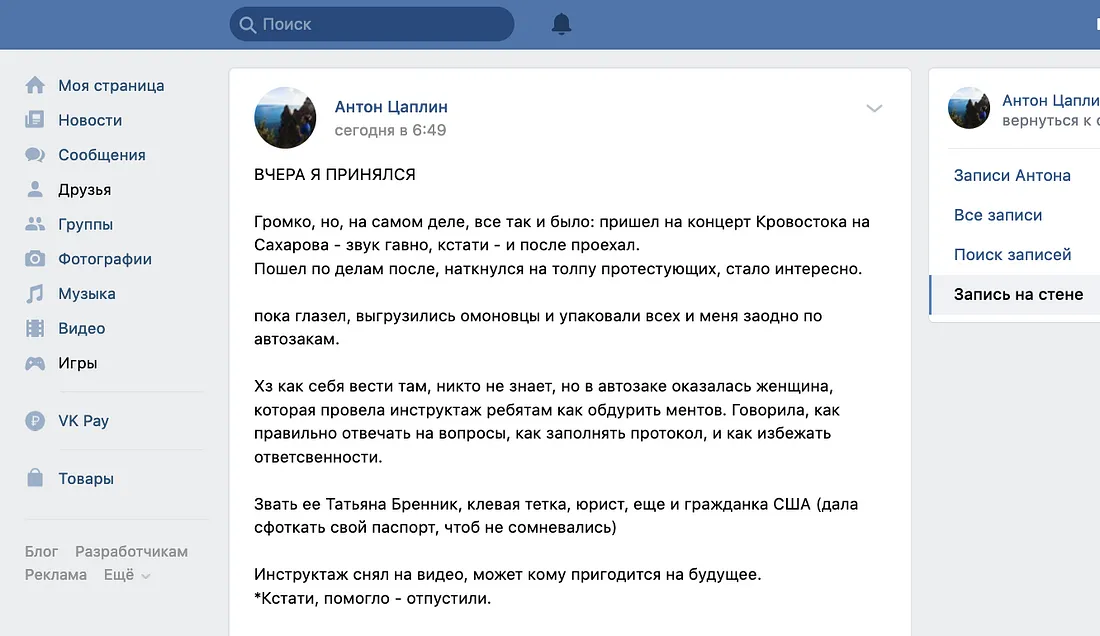

On August 10, police arrested Russian attorney Tatyana Brennik, along with other demonstrators, during the protests in Moscow. Upon a request from police to show her identity document, Brennik presented an American passport — she is a dual Russian-American citizen. Video footage of this scene circulated on the internet. Anton Tsaplin, a user on the Russian social network VKontakte, posted a photo and video footage accompanied by text accusing Brennik of instructing the other detainees on how to handle the police without implicating themselves. His post reignited a wave of allegations about U.S. interference in Russian affairs.

A member of the Federation Council of Russia, Franz Klintsevich, claimed that Brennik’s presence among the detainees was evidence of “direct interference of the United States in Russia’s internal affairs… she is prepared [by the U.S.] to work in special circumstances and knows all the legal nuances and tactics for how to behave in such a situation.“ The State Duma deputy from the ruling United Russia party, Viktor Vodolatsky, added that the United States had sent Brennik to the protests to help detained protesters escape from police and join the crowds again. Klimov, meanwhile, suggested that Brennik may be more loyal to the United States than to Russia.

Allegations of Brennik’s supposed covert agenda grabbed the headlines of pro-Kremlin outlets, which took her presence at the protests as proof of U.S. interference in Russia’s domestic affairs.

Following the surge in allegations against her, Brennik gave an interview to Radio Free Europe explaining her dual citizenship status. She explained that she lives with her family in Russia and is a member of the Lawyers’ Chamber of Moscow Oblast. She has operated a private international law practice in Moscow since 1998. Brennik does not use social media and refused to divulge as to when she had obtained U.S. citizenship.

Brennik said she joined the protests for only 20 minutes, after which she lost her friend in the crowd and decided to sit down and wait for her friend to show up. Brennik claims she was sitting down when policemen approached her from behind and arrested her.

Задержание адвоката Татьяны Бренник 10 августа. Автор видео неизвестен. pic.twitter.com/2GFThspOCD

— Mark Krutov (@kromark) August 14, 2019

She was subsequently taken into detention and placed in a police car, where she met other detainees including Anton Tsaplin, who had posted the video of her to VKontakte. In a separate video, she instructed

Later that day, Brennik was released. On August 23, the Khoroshevsky District Court of Moscow found her guilty of violating the established procedure for holding a rally and fined her ₽10,000 RUB (approximately $150.00 USD). The verdict ended conclusively the discussion of her alleged cooperation with a foreign government, as the Russian court was unable to provide any evidence to prove it.

Conclusion

The allegations of foreign interference in the Moscow protests are not grounded in fact; rather, they are an attempt to discredit the protests and justify the Russian government’s brutal law enforcement response to them. It would also provide yet another excuse for the authorities to diminish the freedom of the media in the country; the authorities have already threatened to ban some Western media from working in Russia as a result of coverage of the election protests.

The unsubstantiated claims of U.S. interference, in particular, form a sharp contrast to the substantial body of evidence supporting the claims that the Russian government interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. When groundless denials fail to help Moscow prove its innocence, the Kremlin indulges in a bit of the old whataboutism, claiming Western countries perpetrate the same extreme behaviors of which they are accused. The Kremlin’s reaction to the protests appears to have been more of the same.

Follow along on Twitter for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.