Cyber-attack knocks out Georgian websites, comes with a surprise

Over 2,000 Georgian government, nonprofit, and private websites hit with malicious code

Cyber-attack knocks out Georgian websites, comes with a surprise

Over 2,000 Georgian government, nonprofit, and private websites hit with malicious code

A large-scale cyber-attack that defaced thousands of Georgian websites with former Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili’s photo on October 28, 2019, was more than a simple case of website vandalism: it included poorly executed malicious code as well.

Georgia has seen a similar attack before, in 2008, when Russia’s military incursion — the territory of which is still the center of a cold conflict between the two countries — was accompanied by cyber-attacks. While there was a similarity with this earlier attack, there is no indication that Russia played a part in this latest event. Both of the attacks, however, were likely aimed at demoralizing Georgian society by sewing confusion and fear as well as instilling a feeling of vulnerability.

The October cyber-attack — likely the largest in the country’s history — affected more than 2,000 websites and targeted multiple sectors, including the websites of the president, courts, civil society organizations, and private companies, as well as two television stations.

While a number of fringe Georgian websites and Facebook pages claimed that Saakashvili himself was behind the attacks, the DFRLab found no evidence to support that attribution.

Previous instances of cyber-attacks on Georgia

Georgia has been a target of similar attacks in the past, most notably by Russian state-backed hacking groups during the 2008 Russo-Georgian War. Hundreds of institutions have been targeted.

In August 2008, security researchers noticed that an escalating series of cyber-attacks began targeting Georgia’s internet infrastructure. The Georgian government accused Moscow of orchestrating cyber warfare alongside Russia’s ongoing military offensive.

At the time, NATO concluded that the hacking of Georgian computer networks “appeared to be coordinated with Russian military actions.” The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, meanwhile, attributed the attack to a “national government” with “high confidence,” noting that it used “a strain of Pinch malware frequently used in Russia.” The Council of Foreign Relations linked the attack to APT28, also known as Fancy Bear, a hacking group associated with Russian military intelligence.

The photo of Georgia’s ex-President

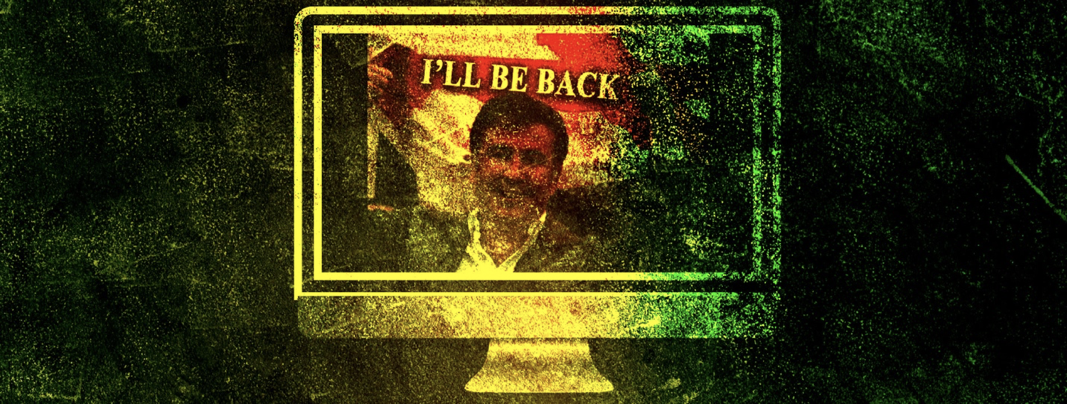

Many of the sites targeted in the latest attack were defaced in the same manner: when visitors navigated to the home page, they were greeted with a full-screen photo of Saakashvili, accompanied by a caption channeling Arnold Schwarznegger in Terminator — “I’LL BE BACK” — superimposed over a Georgian flag.

Saakashvili served two terms as president of Georgia between 2004 and 2013 and is known for his ardent pro-Western views. He is wanted by Georgia’s current government on multiple criminal charges, including abuse of power and wasting state funds; he has claimed the charges are politically motivated.

Georgian Facebook pages and fringe media rush to blame Saakashvili

Shortly after the cyber incident, a number of Georgian Facebook pages as well as fringe Georgian and Russian online outlets started speculating, with no evidence, that the attack was orchestrated by Saakashvili.

The pages shared the photo of Saakashvili displayed on the hacked sites and claimed the hack was organized by the former president and that he will not be able to come back to Georgia despite his best efforts.

In addition to sharing the posts, one of the pages shared an article from a fringe Georgian outlet accusing Saakashvili of being behind the incident.

The DFRLab has encountered several of these pages before, in which they spread false claims that Saakashvili had plotted a coup under the guise of ongoing protests in Georgia.

Alongside the Facebook pages, fringe Georgian and Russian online platforms, including Kremlin-owned Sputnik, spread unsubstantiated accusations that Saakashvili ordered the attack.

The use of a prominent Georgian politician’s picture, particularly one as polarizing as Saakashvili, suggested that this attack had a political motive. It may have been an attempt at political trolling, for example, to sew further divisions within Georgian society.

More than just defacement

The DFRLab discovered that the attack involved more than website defacement, as the file injected by the hacker had poorly written malicious code that appeared to fail to execute whatever its intention was. The hacker tried a technique called steganography, which means concealing hidden information in plain sight — in this case, hiding code within an image. When an image with the code appears on a website, it may execute the code and infect the viewer’s computer with the program set.

The image used in the hack had traces of malicious code embedded toward the corner left side of Saakashvili’s picture.

The small gif on hacked websites was hosted on brother.lviv.ua. Brother is a Chinese company using a Ukrainian domain name that manufactures and distributes sewing and printing machines. The DFRLab found the malicious code embedded within “brother.lviv.ua/content/dot.gif.”

Reviewing one of the sites impacted by the attack — a page called Computex.ge — the DFRLab scanned a gif link found within the site’s HTML code using VirusTotal, which identified the malicious code.

The malicious code required other files including a malware application in order to execute properly. The malware that appeared to be linked to the malicious code — but was not actually present on the webpage — seemed to behave like Nymeria, a malware program that collects user’s personal information. While the malware required was not included, it is possible that users previously infected with it may have triggered the code during this attack, though there has been no reporting indicating any such success.

Connection with brother.lviv.ua

The DFRLab reached out to Brother, the Chinese company linked to the Ukrainian-registered website brother.lviv.ua. When asked to comment on the hack, a Brother representative said that he was unaware that one of the company’s websites was being used as a host mechanism for the hack. The representative mentioned that the website was an old website and is no longer actively updated.

According to Brother’s response, it is possible that the hackers may have gained access to the website for the express purpose of executing the hack on the Georgian websites. It remains unclear, however, why the attackers chose a Chinese vendor’s website registered in Ukraine to host the hack and how they managed to gain access to Brother’s site.

The DFRLab also found that, when a user visited one of the hacked Georgian websites, cookies originating from the Brother website would also be added to the user’s browser. This is non-standard, as cookies are usually only added by the visited website and not from a website not being accessed. The exact nature of the cookies was also unknown, as they could have been a part of the malicious attack or a knock-on effect of the image being hosted on the Brother website (i.e., a standard commercial cookie from Brother, the company).

While the DFRLab could not attribute the attack to a particular entity, the scale and scope of this attack raises the possibility that it could have been state-sponsored. Alternatively, there is some chance that the political nature of the images disguised a more conventional attack aimed at scraping a user’s personal information, as the malware was likely intended to do. The DFRLab will continue to investigate both the attack’s technical structure and the ensuing narrative spread online.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.