Network traces back to anti-Turkey operation originally identified last year

Editor’s Note: This piece was researched in collaboration with BuzzFeed.

Twitter has taken down a network of more than 9,000 Twitter bots that published inauthentic posts promoting the political interests of the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. This “astroturfing” network criticized Turkey’s intervention in Libya — a shared interest of both governments — by targeting Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, DFRLab analysis confirmed through an analysis of the network prior to its takedown. On at least two recent occasions, the network had begun politicizing the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic.

The network of accounts was first reported to Twitter in December 2019 by Stanford Internet Observatory. Meanwhile, it was independently discovered in March 2020 by Indiana-based researcher Josh Russell, while analyzing Twitter posting patterns regarding COVID-19. The accounts were shared with the DFRLab and BuzzFeed for analysis. The DFRLab confirmed its coordinated nature by reviewing accounts characteristics using its Twelve Ways to Spot a Bot methodology.

An enormous platform for public discussion, Twitter remains an ongoing target for amplification campaigns, including political influence operations. The DFRLab has documented astroturfing botnets ranging from promoting a Korean pop band to boosting political campaigns in India and reported extensively on coordinated operations on Twitter to support the UAE’s interests in Libya and elsewhere. Bots on Twitter are wired for a particular purpose like boosting a campaign using a hashtag, increasing the chances that audiences will be exposed to it through Twitter’s trending topics functionality.

In this instance, Russell uncovered the network by searching for coronavirus-related hashtags. While posts related to the coronavirus were not the primary goal of the network, a close look at the accounts suggests they were used for broader political messaging, demonstrating how information ops can be repurposed for different uses.

Crowning the corona response

One example of messages amplified by the botnet was a solidarity video from an account called UAE_v0ice. Though the connection between the botnet and UAE_v0ice, if any, remains to be determined, it was subsequently taken down by Twitter before the rest of the network for violating its policies. A copy of the video can still be found on an affiliated Twitter account, @uaevoiceurdu, which was still active at the time of publication.

The video showed an Arabic speaker expressing support for China during the coronavirus outbreak. The message was posted on February 17, when the outbreak was at its peak in Wuhan, the city in China where the virus was first documented. At that point in time, China had already reported more than 70,000 cases. The video message was intended to highlight the UAE government’s cooperation with China. One month prior to that, Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan tweeted that the UAE was closely monitoring the developments in China and was “ready to provide all support to China.” China and the UAE have a history of positive relations. Last year’s bilateral trade between the two countries reached about $34.7 billion

Analyzing the botnet

As previously noted, the DFRLab was able to identify bot-like behavior across the pro-UAE network using its Twelve Ways to Spot a Bot methodology. For instance, all of the accounts had screen names with random alphanumeric handles, such as @xwdBSuZ3u5VuDdu, @7oPDa5YBSrJPqHS, and @EB94QQBpSTJ0sqW.

Other than the alphanumeric names, the accounts also featured so-called “egg” avatars, since the botnet creator did not take time to individual upload pictures for the accounts. Egg avatars are a common indicator of bot-like activity.

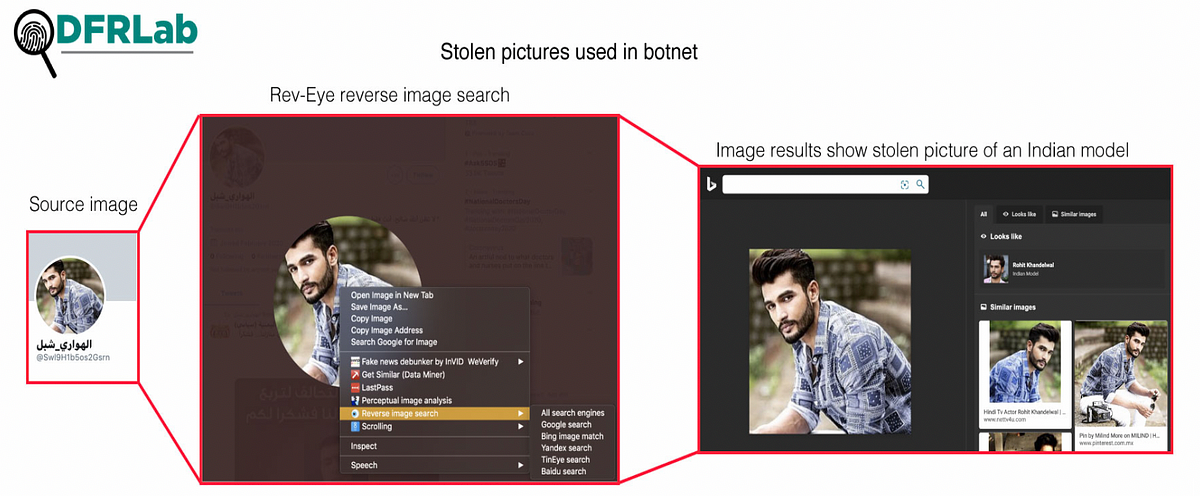

Meanwhile, accounts that had pictures featured either stolen or inauthentic images. For instance, one account used a picture of a famous Indian model as a cover picture. Usage of Indian models for avatars is not uncommon in Middle Eastern botnets since facial characteristics are often similar.

The accounts also had very low following-versus-followers activity, with many of them having neither, indicating that the primary purpose of the accounts was to amplify other content rather than engaging with the Twitter community.

Many of the accounts were batch-created, meaning they were first established on the same day within a short timeframe. Batch creation is one of the most common indicators of a bot network.

Anti-Erdogan rants

Since bot networks are automated, they tend to post verbatim messages, but in this case the accounts were posting similar content rather than verbatim or copy pasted content. The messages had the same political resonance, though. For instance, a number of tweets by accounts used an article from Alghad TV that criticizes Turkey’s alleged support to militias in Tripoli and Misurata that in turn support the UN-recognized Libyan government of national accord, which the UAE opposes. While the text of these tweets are not identical, they shared the same theme: that Turkey’s support of these militias would not be enough, and would lead to additional Turkish intervention.

The article linked within the tweets also criticized Turkey’s intervention. The boost given by bots to this article, along with other anti-Turkish tweets, suggests the network is attempting to amplify the UAE’s disapproval of Libyan Prime Minister Fayez Al-Sarraj, who in turn has expressed disdain for Emirati intervention in Libya. The anti-Turkish tweets also serve as a way to lambaste Turkish President Erdogan for his support of Al-Sarraj and his government.

The Yemen connection

The botnet also covered topics beyond the coronavirus and Libya. Several videos claiming the UAE is supporting Yemenis against Houthi rebels were boosted by the network as well. As a founding member of the Saudi coalition fighting the Houthis, the UAE has played a direct role in the ongoing Yemen war, which has led to the deaths of thousands of Yemeni civilians.

One tweet amplified by the network shows a Yemeni man expressing his support for the UAE trying to make a positive difference.

🎥شاهد / آراء يمنية – لولا الله ثم الإمارات والتحالف لتربع الحوثي في منازلنا… فشكراً لهم.#لن_ننسى_الصقور_المخلصين#الصقور_المخلصين pic.twitter.com/SxpoTWYUSD

— الجمهورية اليمنية (سياسي) (@ana_alyemeny) February 13, 2020

Another tweet that was amplified, though, connects UAE support of Yemenis to the coronavirus outbreak. In the video, a woman thanks the UAE for helping Yemenis when other nations in the region would not, including transporting Yemeni students from the coronavirus hot zone in Wuhan, China.

#شكرا_الإمارات والله اني دمعت فرح بخروج الطلبة اليمنيين من جزيرة ووهان

"الي خلف مامات" الشيخ زايد بيضل اسمه لكل من حكم الإمارات pic.twitter.com/jq9JR9Szvs

— Randa Mohamed (@Randa1Mohamed) February 19, 2020

Political botnets remain an ongoing problem for platforms like Twitter, as they are cheap to deploy and easily replaceable when taken down. In this particular case, the bot net is the latest in an ongoing pattern of inauthentic networks supporting the interests of the UAE and Saudi Arabia, though it is unknown whether those governments directly managed the campaign. With the emergence of the coronavirus, though, it is highly likely we will see additional bot-driven rhetoric exploiting the pandemic for political purposes, both in the Middle East and worldwide.

Kanishk Karan, Research Associate with the Digital Forensic Research Lab, contributed research to this report.