Indian government’s 2G restrictions in Kashmir fail to curb online extremism

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, extremist groups

Indian government’s 2G restrictions in Kashmir fail to curb online extremism

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, extremist groups find workarounds to the digital blockade as ordinary citizens endure restricted access

As part of our effort to broaden expertise and understanding of information ecosystems around the world, the DFRLab is publishing this external contribution. The views and assessments in this op-ed do not necessarily represent those of the DFRLab.

The Indian government recently extended restrictions on access to high-speed internet on mobile devices in the country’s northernmost state of Jammu and Kashmir, impairing locals access to information amid the pandemic.

Domestic media outlets have reported on residents of the state unable to gain regular access to news updates about the virus; local medical professionals unable to download public health guidelines; business owners forced to permanently shut down; and frustratingly slow internet speeds for Kashmiri students trying to finish the school year online.

Despite the mounting difficulties faced by locals as a result of the internet slowdown, on May 5, 2020 the Indian government issued a new order extending existing 2G speed restrictions in the state until May 27, 2020 on the grounds that “high speed internet was likely to be used for coordinating acts of terror both within and from across the border.”

The latest directive, which is the 16th Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services order in the state since April 3, 2020, also claimed that the restrictions do not “cause any impediment in taking measures concerning control of COVID-19.”

The Great Indian Firewall

Residents in the valley have been under an extensive physical and communication blockade since August 5, 2019, when the BJP-led central government unilaterally imposed a series of sweeping amendments to Article 370 (the constitutional provision governing the autonomy and administrative of the state) as well as bifurcation of the state into two administrative union territories, bringing both directly under the control of the central government. Indian authorities deployed 8,000 additional soldiers to Jammu and Kashmir, detained over 2,000 local politicians, including two former chief ministers, and cut all telephone and internet access.

Seven months later, on March 4, 2020, the government reinstated some internet access to locals, albeit with heavy restrictions. These included throttling the speed of data services, only allowing 2G bandwidth for mobile data connections and a government issued whitelist of 301 approved websites. Additionally, they mandated that line-based internet connections would only be available with Media Access Control (MAC)-binding, a system of pairing an individual device’s MAC ID to its IP address, allowing authorities to trace particular posts, tweets, or online activity to a specific individual or device.

For many still living under strict physical distancing orders, internet access serves as an “umbilical cord to the outside world.” On March 13, 2020, website security company Cloudflare reported that peak internet traffic in regions impacted by the coronavirus had increased, on average, by approximately 10 percent.

Yet for residents of the Kashmir valley, the central government’s decision to continue throttling internet speeds in the state despite the onset of the pandemic has created hurdles to information access that have direct consequences for public health.

Contemporary 4G internet services provide users with average download speeds of 150–300 Mbps. 2G, in comparison, provides an average download speed of 65kbps, making it inadequate for local users in Kashmir attempting to access COVID-19 monitoring websites, as well as teachers sharing learning materials.

Online extremism amid the lockdown

The Indian government claims that the restrictions are intended to control terrorism and extremist violence in Jammu and Kashmir, but the state has witnessed a spike in violence with the onset of spring.

According to the South Asia Terrorism Portal, there have been 45 incidents of terror killings in J&K since the beginning of the year. At least 113 causalities have been reported in these incidents, of which 10 were civilians, 25 members of security forces, and 78 militants. As of May 12th, 2020, J&K has already witnessed 138 terror-related incidents, demonstrating how the internet shutdowns have not resulted in the end of terrorism.

Extremist propaganda posted by militant groups on Telegram, Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp and other social media sites continues unabated, as malicious actors seek to take advantage of the paucity of credible sources reporting on the ground to spread disinformation and rumours. The DFRLab has previously reported on how actors in India and Pakistan have taken to Twitter to exploit the informational vacuum created in the state following the BJP-led central government’s imposition of the digital blockade.

Multiple Telegram channels run by groups such as Jaish e Muhammad, Hizbul Mujahideen, Laskhar e Toiba, and the newly formed The Resistance Front continue to operate and attract a significant audience online. A Twitter account purporting to be linked to Al Aqsa Media Jammu and Kashmir managed to get 1,475 followers amid the digital blockade before it was removed by the authorities.

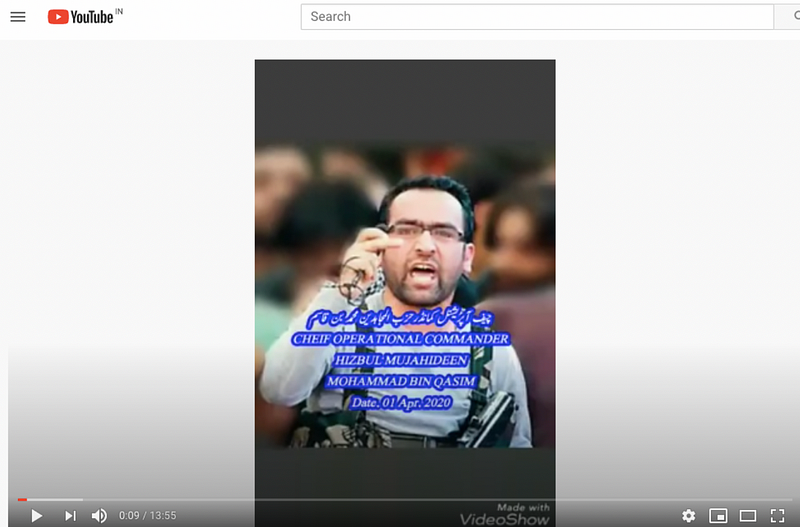

Similarly, the operational commander of Hizbul Mujahideen issued an audio message on Facebook on April 1, 2020 that was widely shared, liked, and commented upon in Kashmir. Before that, another clip issued by the same militant appeared on the internet on April 11 and was seen by over 20,000 people on YouTube.

Apart from these clips, hundreds of images, infographics, and text statements are uploaded on these Telegram channels every day, providing ample evidence to suggest that internet restrictions have failed to curb the proliferation of militant propaganda online. In some cases, these militant groups appear to be capitalizing on Kashmiris’ growing frustration with the physical and digital restrictions in an attempt to attract them to extremist content.

Academics studying the effect of network shutdowns in dissident movements in India argue that internet shutdowns are an unproductive strategy in the long run, particularly within the context of a festering insurgency, with the use of informational blackouts accelerating the adoption of violent tactics that are less reliant on effective communication and coordination.

Delhi’s latest decision to extend the ban on high speed internet in Jammu and Kashmir ties into the BJP-led central government’s penchant for heavy-handed digital tactics. India is now the world leader in internet shutdowns according to digital rights NGO Access Now. The government has wielded access to the internet and mobile data as a coercive tool to exact political concessions and enforce “compliant behavior” from a targeted population.

According to data collected by the internet shutdown tracker, an open-source tool created by the Software Freedom Law Centre India, a domestic digital rights NGO, India has had 377 internet shutdowns since 2014, with 172 of these shutdowns occurring in Jammu and Kashmir alone.

On March 31, 2020, the Foundation for Media Professionals, a local civil society group, filed a petition before India’s Supreme Court appealing for the restoration of 4G internet services in the state, arguing that the continued internet shutdown during the pandemic constituted a gross violation of the fundamental rights to healthcare, education, livelihood, and justice enshrined in the Indian constitution.

These concerns were reiterated in a report by Human Rights Watch on Delhi’s decision to continue throttling of internet speeds in the valley, with Deborah Brown, a senior digital rights advocate, arguing that “shutdowns directly harm people’s health and lives, and undermine efforts to bring the pandemic under control.”

Taken together, the Indian authorities growing proclivity for applying internet restrictions against its own population ties into a broader wave of digital authoritarian practices by a range of illiberal democracies across the developing world. This export of digital authoritarian tactics has seen a growth in state organizations operationalizing the internet as a mechanism to surveil, repress, and manipulate domestic and foreign populations.

Ayushman Kaul is a Research Assistant, South Asia, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab

Khalid Shah is an Associate Fellow with the Observer Research Foundation.