Why combating misinfo effectively requires addressing affective polarization among the general public

As part of our effort to broaden expertise and understanding of information ecosystems around the world, the DFRLab is publishing this external contribution. The views and assessments in this analysis do not necessarily represent those of the DFRLab.

As the 2020 U.S. presidential election approaches and the coronavirus pandemic continues to evolve, conversation in the United States has turned back to online disinformation campaigns, fact-checking, and social media policy — if it ever really turned away.

There is considerable debate about the efficacy of fact-checking, in part because of conflicting findings in academic studies on whether administering a factual correction leads an individual to reassess their belief in the inaccuracy. One model supposes that people engage in motivated reasoning: even when presented with expert consensus and factual information, they pick and choose which facts to believe based on whether those facts conform to their worldview. Another model argues that the extent of the “backfire” effect — the notion that trying to correct mistaken beliefs actually reinforces conviction in those beliefs — has been overstated.

Regardless of which model one adopts, fact-checking is undeniably important: even when it fails to correct mistaken beliefs, it provides a record of the truth, which is critical to democracy and accountability. But there is also evidence that existing models of how misinformation works — and how factual corrections affect beliefs — need revising.

This piece reports the results of a survey experiment run with 1,000 respondents on Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online crowdsourcing marketplace. The results demonstrate an understudied aspect of misinformation and efforts to combat it: its emotional dimension and relationship to polarization, one of the most significant, measurable features of contemporary U.S. politics. The study provides evidence that misinformation has an effect beyond convincing its consumers of something untrue — it creates polarization that persists even when underlying falsehoods are corrected.

Polarization

While there are several different forms of polarization — affective, elite, perceptual, and more — all are at their highest levels since the Civil War and Reconstruction Era. Anecdotally, much online misinformation occurs in a polarized, emotional context, from political debates to anti-science arguments over vaccines and the roundness of Earth.

A developing body of research indicates that this polarized environment significantly affects how misinformation is consumed, processed, and integrated into an individual’s existing belief system. Several studies have found that political partisans have a tendency to engage in motivated reasoning: when presented with factual information on a sensitive political issue, they pick and choose which facts to believe based on the degree to which the presented information support their existing beliefs (see Schaffner and Roche, Drummond and Fischhoff). Relatedly, studies on the efficacy of fact-checking in the context of U.S. political misinformation have shown that, on controversial, polarizing topics, even when individuals accept corrections as factually accurate, they do not revise their policy preferences accordingly (see Swire et al., Hopkins, Sides, and Citrin, Esberg and Mummolo, and Flynn et al). Respondents believed corrections about crime rates, immigration, WMDs in Iraq, and so on, but they failed to change the preferences that should have been built on of those facts accordingly.

These were not instances of rejected corrections — instead, subjects encountered new information, often in direct contradiction with their previously held beliefs, and accepted it as factually accurate, but they didn’t adjust their related policy attitudes. In other words, even with new, correct information, respondents did not express a change in what they wanted. This was not the case for all policies: less controversial topics such as state education budgeting did respond to fact-checking. These studies demonstrate a disconnect between facts and policy preferences. The fact-checks relayed the truth successfully, but they did not change minds, calling into question the assumption that suboptimal policy preferences are based solely on bad information.

Testing the relationship between polarization and misinformation

Drawing on previous research, this study presents an alternative explanation for why some consequences of misinformation are resistant to fact-checking in certain contexts. Political misinformation may leverage strong political identities to cause harm by increasing affective polarization, defined as the difference in a subject’s positive feelings toward parties, politicians, and figures they agree with and their negative attitudes toward those with which they disagree. Fact-checking fails to remedy that polarization and, in some cases, even exacerbates it. Because affective polarization is based in emotion as much as in fact, the correction’s reach is limited: even if it provides better quality information, it fails to correct the broad emotional attitudes toward politicians and parties that were originally stirred.

A survey experiment run on 1,000 subjects via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform tested three hypotheses derived from this model. First, exposure to misinformation increases affective polarization, regardless of whether the misinformation is congruent or incongruent with the consumer’s views. Second, the effects of misinformation are mediated by political identity — the stronger, more cohesive the identity, the greater the increase in polarization. Third, and most troubling, corrections in no way temper the polarization. In plain English, misinformation polarizes it consumers regardless of whether or not they agree with it, and particularly for the most partisan consumers.

Amazon Mechanical Turk is an online labor marketplace popular among experimental social scientists as a subject recruitment tool, particularly for treatment experiments. Participants receive small sums of cash in exchange for completing “HITS,” or quick “Human Intelligence Tasks” posted by requesters. While the MTurk population differs from the general population in some ways — the former is, on average, younger, more educated, and more online than the latter — several replication studies in political science, in particular, have found that samples obtained via MTurk consistently produced near-identical results to national samples when analyzing treatment effects.

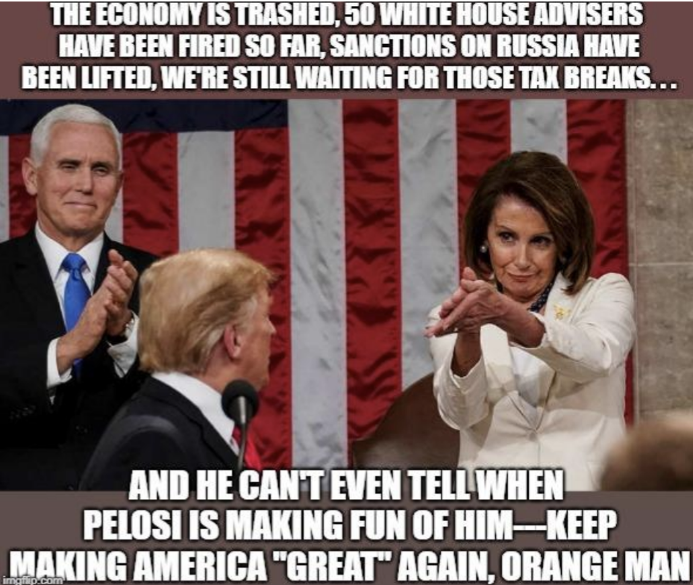

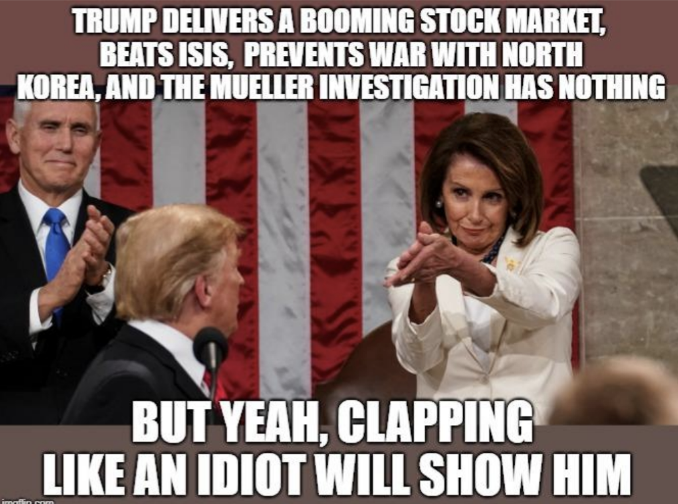

Subjects were sorted based on their self-identified political affiliations and a battery of policy preference questions before being randomly assigned to one of five groups: a control group, two groups exposed to misinformation without corrections, and two with corrections. The treatment consisted of some combination of congruent/incongruent misinformation and the presence or absence of a correction. Within the four treatment groups, half received misinformation congruent with their political positions, and half received incongruent misinformation. The misinformation itself was formatted like a Facebook post, using an image from the 2018 State of the Union speech with four items of accompanying text-based misinformation, all with either a conservative or liberal slant (the items were selected based on current events at the time of the experiment and, as such, are now outdated). After exposure, affective polarization was measured as the difference between respondent attitudes toward the Democratic and Republican parties, as well as toward President Trump and Speaker Pelosi.

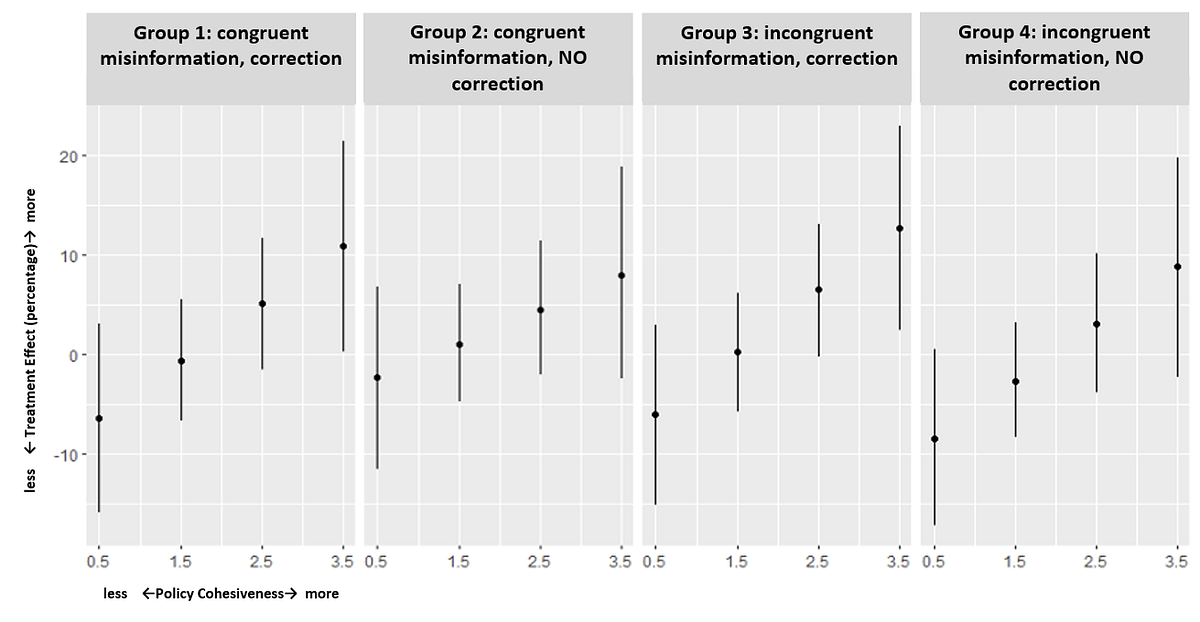

The following model tested the first and second hypotheses. The cohesiveness variable was derived from respondent answers to policy preference questions: more answers aligning with either a liberal or conservative ideology led to a higher score, indicating greater cohesiveness or partisanship.

Affective Polarization ~ Treatment + Cohesiveness + Treatment:Cohesiveness

The following graphs visualize the resultant regression table. The y-axis measures the effect of the treatment — exposure to misinformation and, sometimes, a correction — on polarization as compared to the control group. The x-axes show the different degrees of policy cohesiveness within each treatment group. Subjects with high policy preference cohesion (i.e., strong political identities) were on average 10 percent more polarized after exposure to misinformation, whether or not it agreed with their views.

The consistent upward trend within each group shows that those with the least cohesive views — the two lines at the left of each group — were generally unaffected by misinformation, and the two most cohesive groups (to the right) were polarized by it. Partisanship caused the treatment misinformation to polarize subjects.

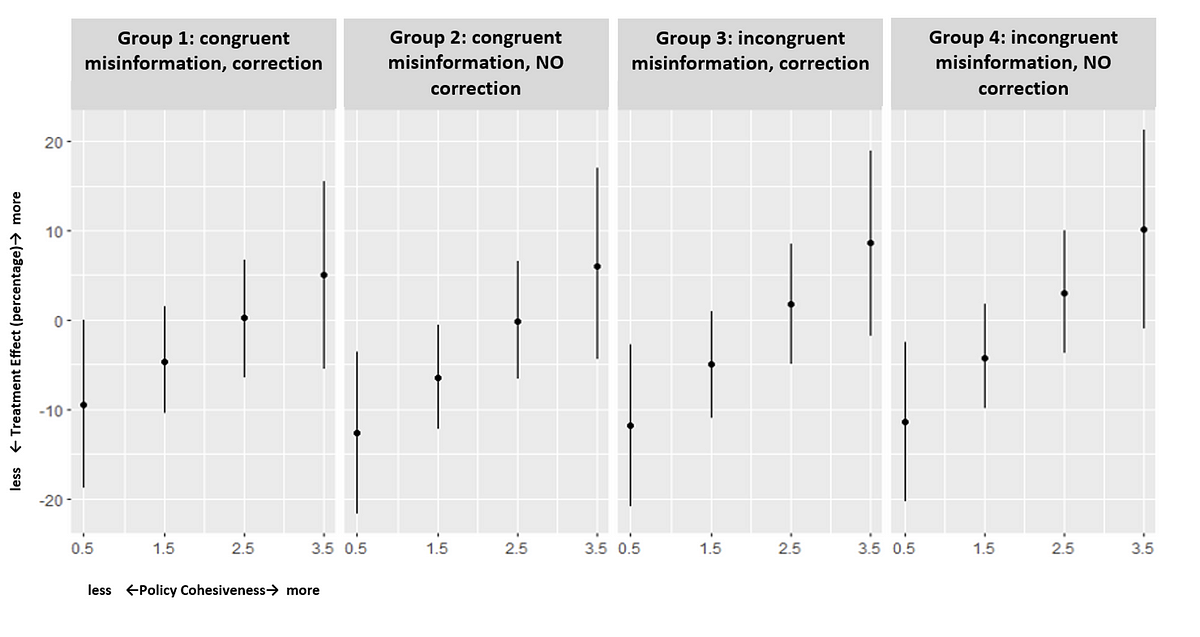

To test the third hypothesis, that corrections do not affect polarization, a variable representing corrections and an interaction term between correction and policy cohesion were added to the original model:

Affective Polarization ~ Treatment + Cohesiveness + Treatment:Cohesiveness + Correction + Correction:Cohesiveness

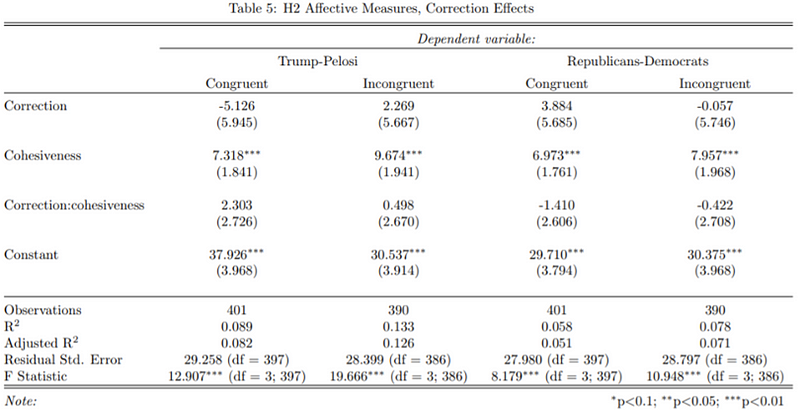

The following regression table, truncated for readability, illustrates corrections’ complete lack of a statistically significant effect on polarization — it was impossible to separate any effect caused by the correction from random noise, signified by the lack of asterisks next to their coefficient values.

In short, misinformation polarized subjects, whether or not they agreed with it, so long as they held somewhat consistent political views. That polarization was completely unaffected by factual corrections, regardless of their success or failure.

A polarization feedback loop

This survey experiment demonstrates that exposure to misinformation, even just once, can increase affective polarization significantly, and in a manner that subsequent corrections fail to reduce. The implication is that the way we combat misinformation needs rethinking. Remedying the harmful polarization resulting from misinformation is critical, and so too is making systems more resilient to polarization in the first place. An easily polarized electorate and partisan dynamics prone to bifurcation turn from political idiosyncrasy to liability in an era of inexpensive, far-reaching mass digital communication.

While this study focuses on the United States, international comparisons provide useful insight. There is some evidence that the effects of factual corrections on political attitudes differ based on national context. Furthermore, American politics, with its two-party system and first-past-the-post voting, is particularly prone to polarization, but that polarization is also relatively easy to measure. Future research should consider manipulating polarization and political structures as variables when studying how misinformation operates in different contexts. It should also examine the downstream effects of repeated exposure to misinformation, and subsequent corrections: it may be that a single correction administered in a controlled environment does little to change a person’s political preferences, but that consistent corrections over a longer period of time do affect how people process and evaluate information. The opposite may also be true — that repeated exposure to polarizing content is even more difficult to correct than single instances.

Polarization is not just a product of misinformation, though — it also helps create it. Several studies correlate affective polarization with an increased tolerance for factual inaccuracy, particularly on the political right. Polarization may even fuel greater demand for misinformation among consumers. As a result, we are likely experiencing a vicious cycle of negative feedback: polarization begets and enables misinformation, which in turn aggravates polarization. Disrupting this cycle will require new policies in addition to dogged fact-checking. Keeping a record of the truth is crucial for democracy, studying misinformation, and providing people with accurate information, but setting the record straight is far from a complete solution. There is another entirely separate dimension of misinformation — its relationship to affective polarization and the emotional attitudes undergirding that polarization — that needs addressing as well.

Stewart Scott is a Program Assistant with the Atlantic’s Council’s GeoTech Center.

Follow along on Twitter for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.