Patriotic astroturfing in the Azerbaijan-Armenia Twitter war

Renewed tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan

Patriotic astroturfing in the Azerbaijan-Armenia Twitter war

Renewed tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan brought out Azerbaijan’s patriotic web brigades on Twitter

Amid renewed clashes at the Armenia-Azerbaijan border, patriotic web brigades of pro-Azerbaijan accounts waged a parallel online campaign by astroturfing several pro-Azerbaijan and anti-Armenian hashtags on Twitter.

Armenia and Azerbaijan share no diplomatic relations as a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict — the longest-running ethnic and territorial dispute resulting from the collapse of the Soviet Union. While recognized as part of Azerbaijan by the international community, the territory, which is predominately ethnic Armenian, has been under the de facto control of ethnic Armenian forces since a 1994 ceasefire. The latest clashes, which erupted on July 11, 2020 and have killed at least 16 people, represent the most serious escalation of the conflict since the so-called Four Day War in 2016.

The ongoing military dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan has long had an information warfare component. While neither country has an official cyber army, hacktivist groups from both sides have launched cyber attacks on the other’s government and media websites, and this latest escalation is no exception. The conflict has also played out on social media, between Armenian and Azerbaijani users. Both Azerbaijanis and Armenians have launched hashtags campaigns focused on the current hostilities in recent days: Armenians are primarily organizing under #TavushStrong and #AzerbaijanAggression, while pro-Azerbaijani accounts are using a number of hashtags, most prominently #ArmenianAgression and #KarabakhIsAzerbaijan.

The traffic flows the DFRLab analyzed, however, showed that the pro-Azerbaijan hashtags were heavily manipulated, with a small group of high-volume accounts responsible for a significant portion of mentions. There was no evidence that these accounts were fully automated “bots” — rather, they appeared to be curated by highly dedicated human users, many of them college students or belonging to pro-regime youth groups.

The scale of the Twitter war

The DFRLab collected nine top hashtags from both sides from July 12 to July 18, 2020 to compare the relative traffic flows. This comparison revealed that the pro-Azerbaijan hashtags significantly surpassed the pro-Armenia hashtags, with roughly 1 million mentions for the former to around 31,000 for the latter. A close-up of both traffic flows also showed the pro-Armenian hashtags displayed an ebb and flow in mentions volume more characteristic of organic traffic, while the pro-Azerbaijani hashtags demonstrated sharp peaks — mostly consisting of retweets — at 2 p.m. every day. Because the disparity in traffic flow was so stark, the following analysis focuses on the pro-Azerbaijan hashtags.

Measuring traffic manipulation

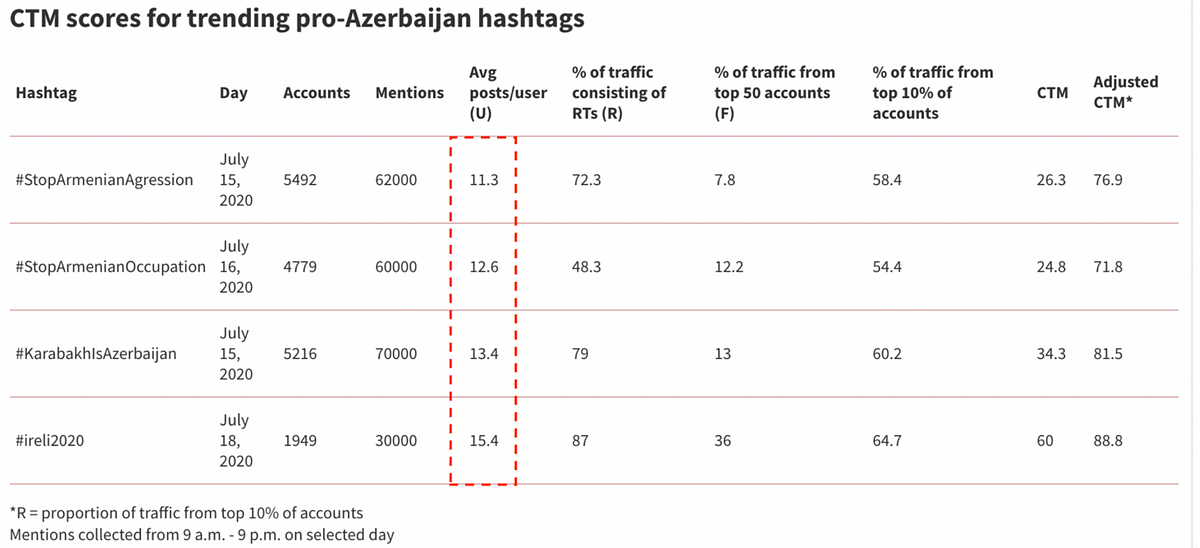

The DFRLab used a measure called the Coefficient of Traffic Manipulation (CTM) to analyze four of the top pro-Azerbaijan hashtags that trended between July 12 July 18, 2020: #StopArmenianAgression (misspelled), #StopArmenianOccupation, #KarabakhIsAzerbaijan, and #ireli2020.

First developed by DFRLab Non-Resident Senior Fellow Ben Nimmo for the Oxford Computational Propaganda Project, the CTM measures the likelihood that a given traffic flow is manipulated — defined as “an attempt by a small group of users to generate a large flow of Twitter traffic, disproportionate to the number of users involved.” As a relative, rather than absolute measure, it should be used alongside other indicators, but can nonetheless serve as an early-warning sign of attempts to distort online conversations.

In early studies using the CTM, organic, non-manipulated control samples scored a CTM of 12 or lower. In this case, all four of the studied hashtags scored at least double that, with one hashtag — #ireli2020 — scoring a CTM of 60. This hashtag is a reference to the pro-regime youth organization IRELI, which is known to operate troll accounts harassing journalists and regime critics as well as run a “social media academy” for youth. Originally funded and sponsored by the Azerbaijani government, IRELI had strong ties to the regime until mid-2014.

These scores fell short of the highest CTM the DFRLab has ever recorded — 138 for a hashtag boosted by accounts linked to civilian militias in Venezuela — but they were in the same range as other manipulated hashtags studied, such as #TheBlockadeKills and #CubaCoopera, as well as hashtags from the original Oxford study on the CTM: “Qadhafi of the Gulf” (translated from Arabic) and #StopAstroTurfing.

Disaggregating the scores revealed that the four hashtags had a particularly high number of average posts per user: between 11 and 16. In control samples, this number has been within 2–4 tweets per user. (In the case of #TavushStrong, one of the popular pro-Armenian hashtags since the recent fighting at the border started, the average number of tweets per user was 2.3 at the hashtag’s peak on July 18.)

This indicates a possible political astroturfing operation — when a small, coordinated group of accounts post at an extremely high volume to artificially create the impression that an online movement has more organic support than it actually does. This finding does not mean that there were not authentic pro-Azerbaijan users employing pro-Azerbaijan hashtags as an expression of online civic action — but rather, that these efforts were significantly boosted by a small group of highly dedicated accounts posting at a high volume.

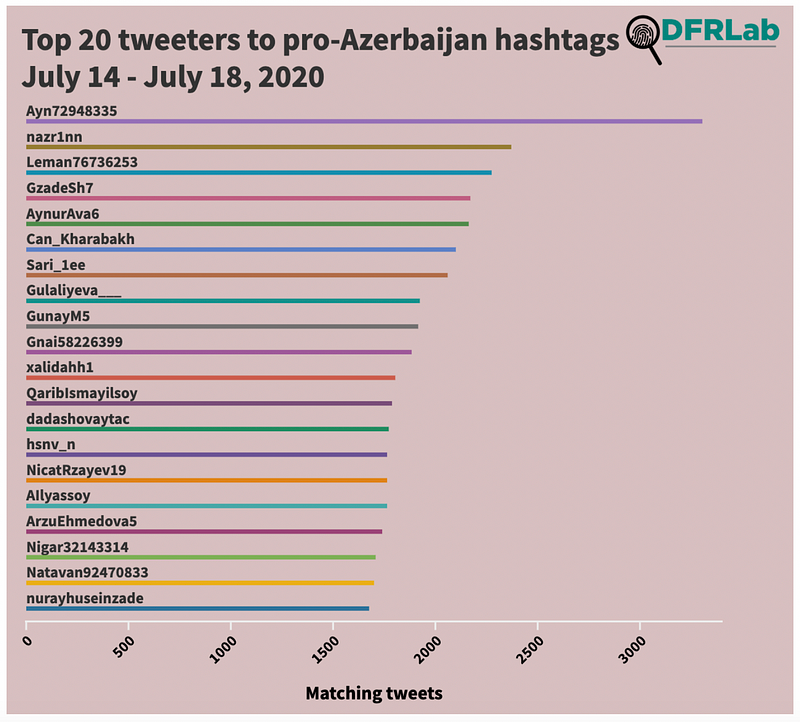

Identifying the top tweeters

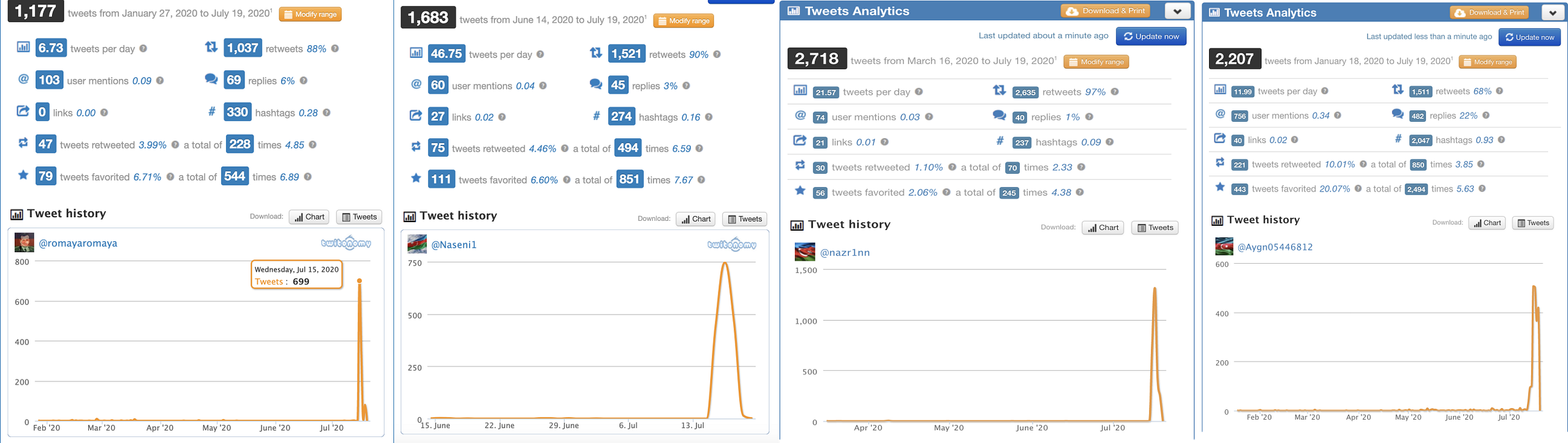

Across all of the top pro-Azerbaijan hashtags analyzed, dozens of accounts tweeted to the hashtags well over a thousand times between July 14 — July 18, with all of these accounts posting over a hundred times a day.

Examining some of these individual high-volume posters revealed three types of accounts boosting the hashtags.

Once-dormant accounts. These accounts had been created weeks prior and had seldom or never tweeted. Once the conflict erupted, they began posting hundreds of tweets in a single day.

Retired accounts. A second group of accounts did the inverse: they were created early on in the fighting (July 13–15), posted hundreds of tweets on the first one or two days, then largely stopped posting.

Steady high-volume posters. The last group of accounts maintained a steady high volume of posting throughout the week, posting at around 300–500 tweets per day on a consistent basis.

All of these accounts posted at a rate not often seen in authentic accounts, even those of online activists or other types of power users. This does not necessarily suggest, however, that these accounts were bots — the DFRLab found no evidence that they were tweeting using automation clients, or that they were tweeting 24/7 — two of the most reliable indicators of automation. Rather, most of these accounts were likely operated by highly dedicated human users, who may or may not have employed some automation to maintain such a high volume of posting.

Most of these profiles were anonymous, featuring profile pictures of the Azerbaijani flag or other national symbols and no biographical information. About 50 of the 483 most active accounts, however, listed universities in Azerbaijan in their bios, sometimes with class years, indicating that they were students. Katy Pearce, a professor at the University of Washington who has conducted numerous studies on social media use in Azerbaijan, has previously detailed how pro-government youth groups in Azerbaijan have mobilized to troll and attack members of the opposition on Twitter and artificially game trending hashtags in a coordinated manner.

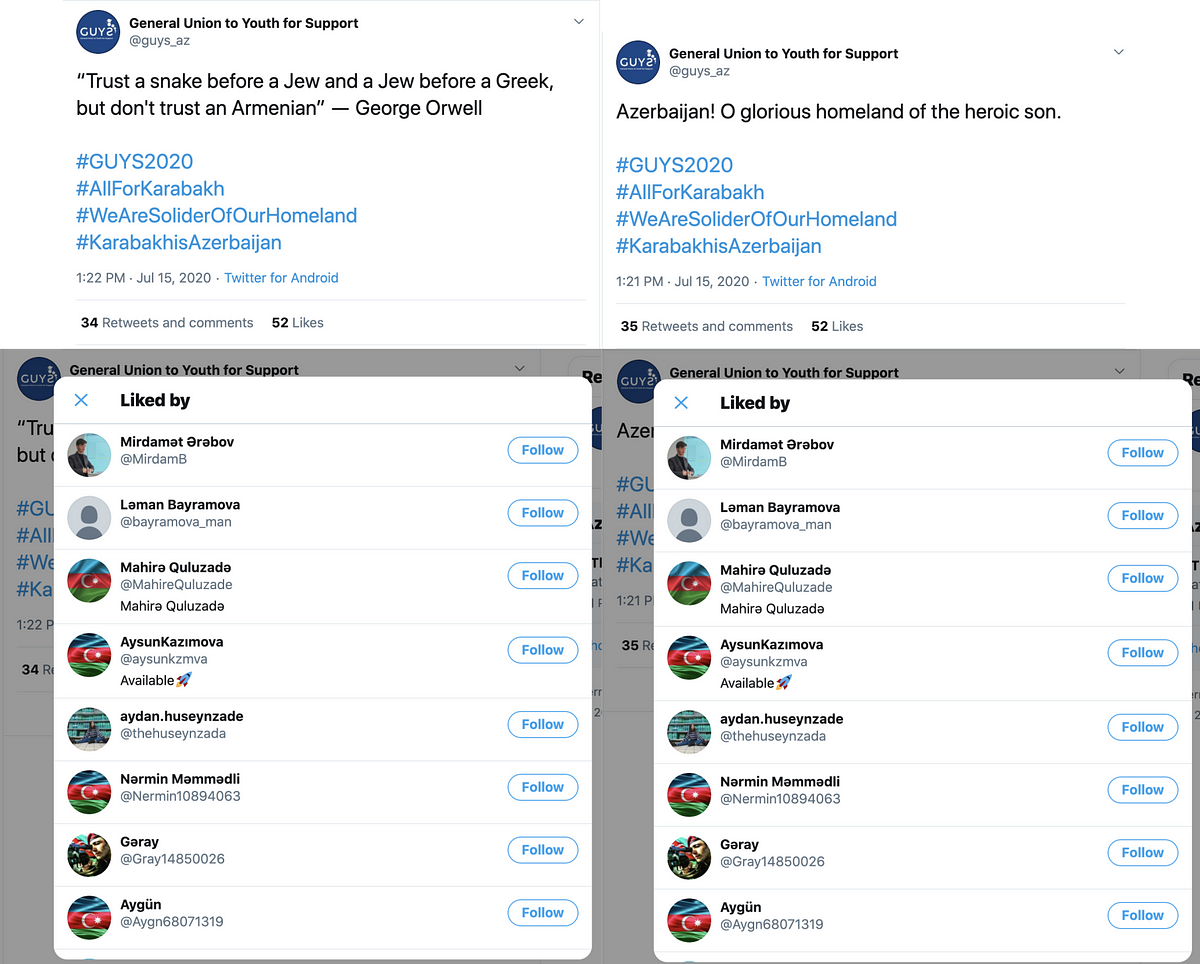

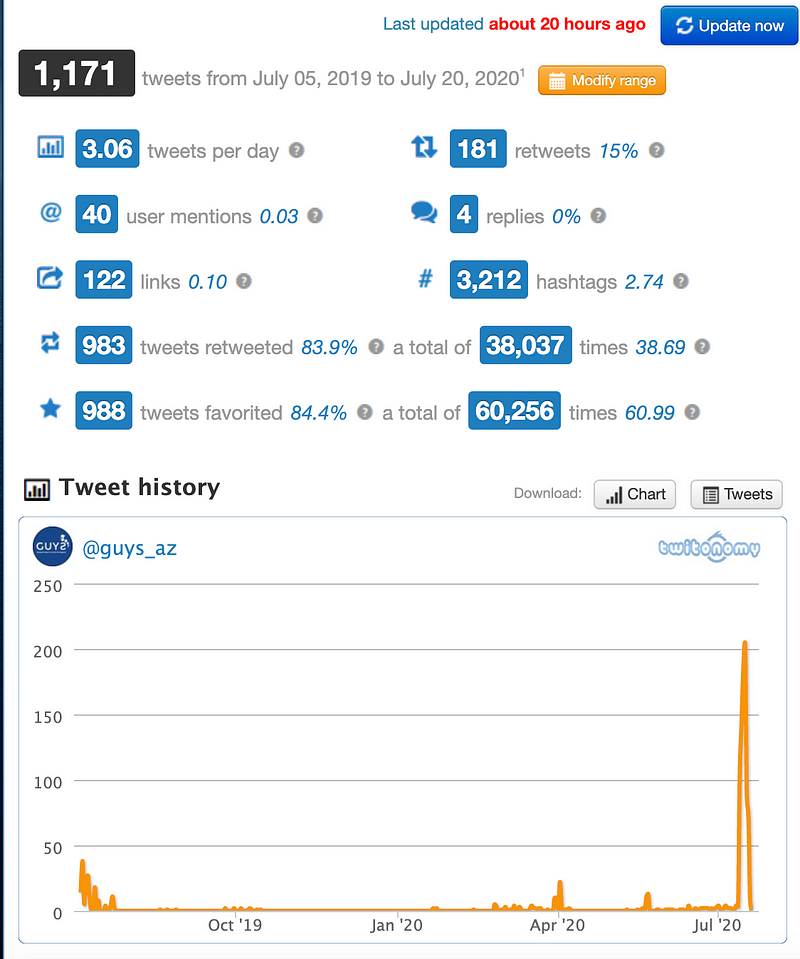

There was some evidence of coordinated manipulation on the part of pro-regime youth organizations. The DFRLab found a small like/retweet ring around the account @guys_az, the official account of the General Union to Youth for Support (GUYS), a youth organization created in 2019 to support President Ilyam Aliyev’s youth development policy. On its Instagram page, GUYS links to a Google form which it uses to recruit members to “online volunteering” programs.

Twitter shows likes on a tweet in the same order as the likes occurred — this means that the same accounts liked this pair of tweets in the exact same order, indicating coordination.

Like many of the accounts the DFRLab came across, the @guys_az account dramatically ramped up its activity when the latest hostilities erupted.

Identical creation dates

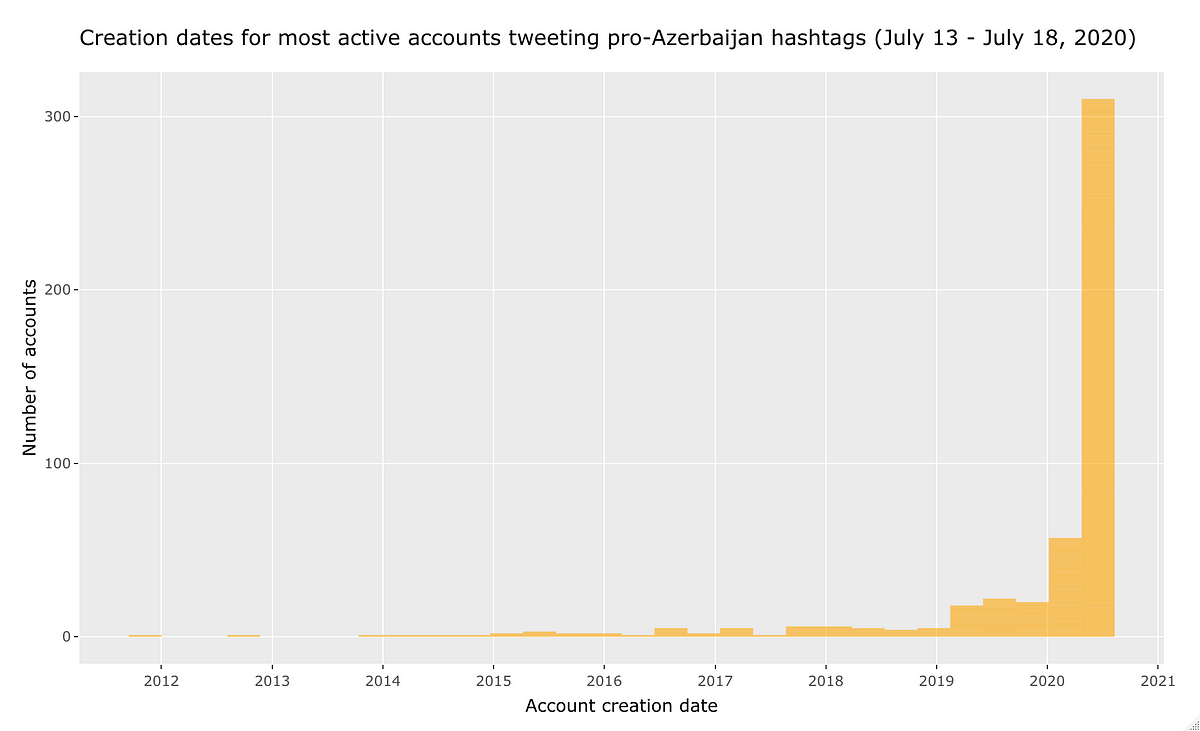

The DFRLab downloaded data for the top 500 most active accounts tweeting to the hashtags from July 13 — July 18 and obtained creation dates for 483 of them (17 of the accounts had already been suspended).

A great proportion of these hyperactive accounts were created over the past week. On July 15 alone, 117 accounts were created, with the next most popular creation dates being July 16 (67 accounts) and July 14 (32 accounts).

These accounts’ recent creation dates, coupled with the fact that they almost exclusively tweeted or retweeted pro-Azerbaijan hashtags, suggested that their operators likely created them for the express purpose of boosting the hashtags as the border flare-up escalated.

When coordinated activism becomes traffic manipulation

Hashtags are engineered for virality, and the strategic use of hashtags to draw attention to social and political events is a recognized form of online activism. Furthermore, college students are more likely to be politically engaged and technologically literate, and thus perhaps more likely to incorporate hashtag activism into their political speech online.

But Azerbaijan has an entrenched state propaganda apparatus and a history of employing computational propaganda and patriotic trolling for information control. A 2018 report from the Oxford Internet Institute classified Azerbaijan’s organizational capacity for social media manipulation at “medium” — alongside several states with a well-documented tradition of large-scale government-sponsored social media manipulation, such as India and Pakistan. This semi-institutionalized structure for social media manipulation relies heavily on pro-government or party-affiliated youth groups — a model not unique to Azerbaijan.

In this particular case, the DFRLab found roughly 500 accounts, of which at least two-fifths were recently created, posting to pro-Azerbaijan hashtags hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of times per day as fighting continued on the Armenia-Azerbaijan border. While these accounts did not account for all of the traffic to pro-Azerbaijan hashtags from July 13 — July 18, they constituted the majority for all four hashtags studied at the moment they reached their peak in mentions.

Zarine Kharazian is Assistant Editor with the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (@DFRLab).

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.