Spanish-language COVID fact-checking spun for political purposes

Audiences amplified apolitical fact-checks for their

Spanish-language COVID fact-checking spun for political purposes

Audiences amplified apolitical fact-checks for their own political agendas

In the wake of COVID-19, several independent fact-checking initiatives have emerged to verify content specifically for Spanish-speaking audiences. Two of the most prominent, @covidmx and @esp_covid19, were created in mid-March 2020. They focus on providing timely and authoritative COVID-19 information to Latino communities, primarily in the United States and Mexico, and have amassed a sizable audience.

Little is currently known, however, about who these audiences are and how they are engaging with the content — and potentially exploiting it for political purposes — of these fact-checking organizations during the pandemic. The UNAM Civic Innovation Lab joined forces with the DFRLab to understand more about these audiences. The investigation found political influencers in Mexico, including former presidents and political news reporters, who have selectively cited the work of these initiatives when it suited their political agendas, causing others to question the validity and neutrality of their fact-checking despite the consistent quality of their work.

Understanding the audience

The investigation collected all of the tweets from @esp_covid19 and @covidmx, as well as the timelines of all of the accounts that either mentioned the organizations in their tweets, replied to them, quoted them, or retweeted them. These accounts will be referred to as the fact-checking organizations’ primary online “audience” throughout this report. Based on this data, both fact-checking efforts had nearly 21,000 audience members combined on Twitter (i.e., around 20,869 individual accounts that engaged at least once with the organizations’ tweets between March 13 and June 25, 2020).

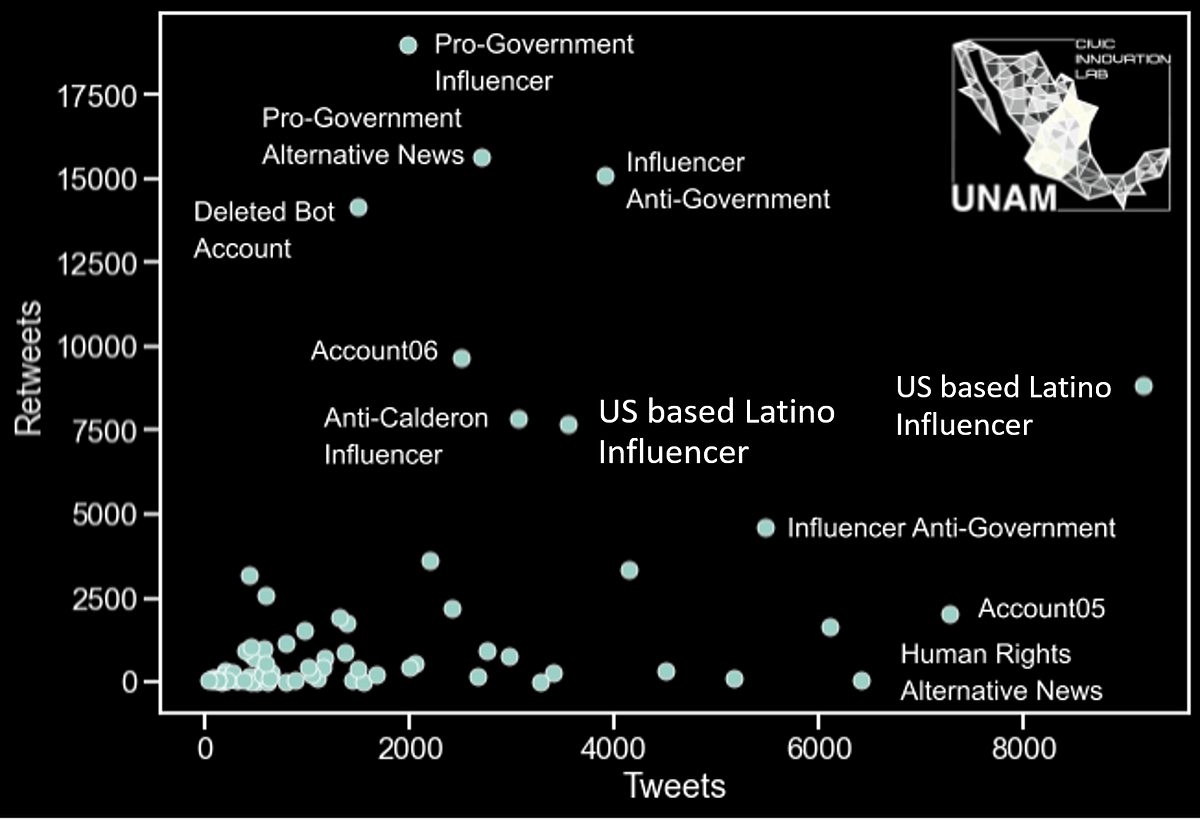

To understand what kinds of accounts engaged with the two fact-checking organizations on social media, the researchers plotted the total number of tweets each audience member generated on their timelines against the total number of retweets they amassed.

The outliers in the plot represent influencers (accounts that received a large number of retweets) as well as accounts that were highly active (generated a large number of tweets). The outliers were primarily bot-like accounts (initially identified via Botometer, then qualitatively investigated), political influencers, and news accounts. Although the fact checkers focused on verifying information about the pandemic, none of the most active influencer accounts that engaged with them belonged to health institutions or were health officials. The most active accounts also did not belong to any current government official. Notice that this does not mean that government officials or healthcare officials did not interact with the fact-checking organizations. They were simply just not among the most active online accounts that we identified.

A social network analysis of both fact-checking organizations’ audiences — again, those accounts that directly interacted with the fact checkers — revealed that @covidmx had a much wider audience than @esp_covid19. The former’s audience size was likely because @covidmx is a spinoff of @VerificadoMX, a Mexico-based initiative comprising NGOs, news outlets, and academics best known for fact-checking information around natural disasters in Mexico as well as the 2018 Mexican presidential elections.

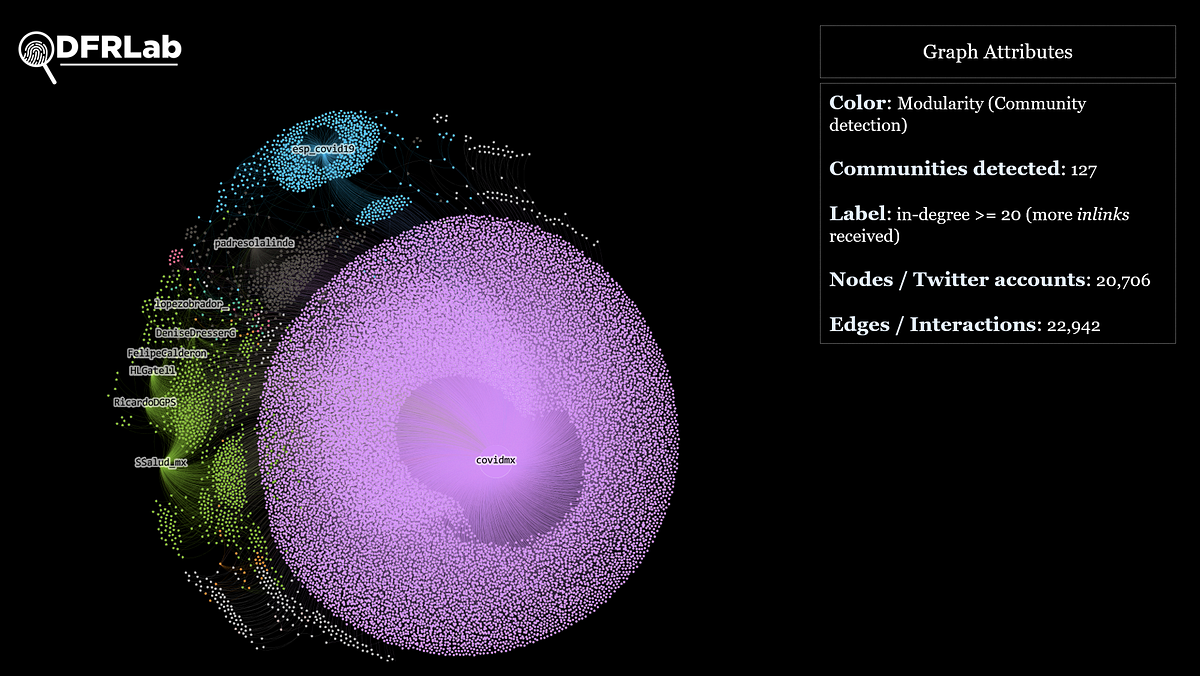

The graph below shows a user-to-user network of tweet mentions, retweets, quotes, and replies (i.e., audience interactions), posted between March 13 and June 25, 2020, involving @covidmx and @esp_covid19. Each node in the network represents an account that was also included in the tweets the audience generated about these two fact-checking organizations. The directed edges indicate the flow of information. An edge from one node another indicates that the former has retweeted, quoted, mentioned, or replied to the latter.

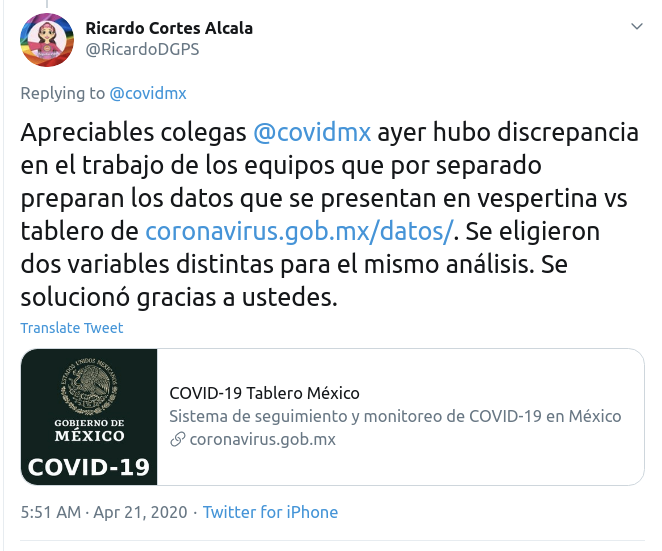

The audience of @covidmx was not only larger but also well-connected to a range of actors and institutions. Many of those who interacted with the organization’s tweets were also connected to high-profile healthcare accounts such as @HLGatell (Mexico’s main spokesperson on the COVID-19 pandemic), @SSalud_mx (Mexico’s Health Ministry), and @RicardoDGPS (the Mexican government’s director of health promotion). This is somewhat expected, given that @covidmx focuses on fighting health misinformation.

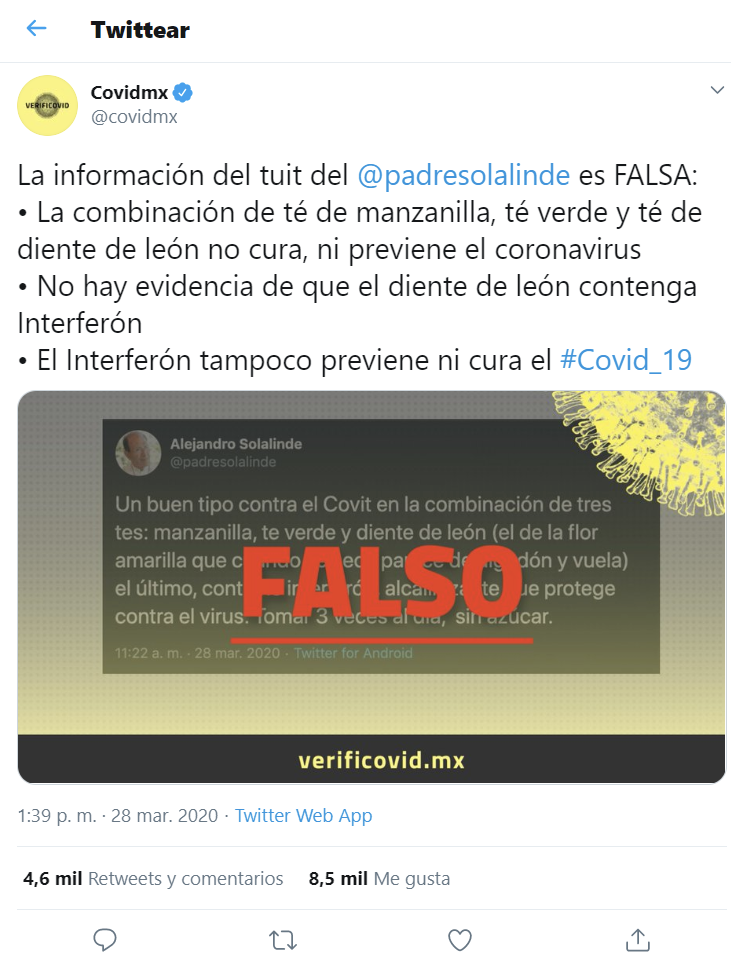

@covidmx’s audience also connected to political figures, including current Mexican president @lopezobrador_ and former president @FelipeCalderon, journalists such as @DeniseDresserG and religious figures such as Catholic priest Alejandro Solalinde (@padresolalinde). @covidmx had previously debunked Solalinde’s public COVID-19-related health advice. Notice that while the audience connected to certain political actors, such as Mexico’s current president, it does not mean that the Mexican president directly interacted with the fact-checking organizations, which the investigation did not find evidence of such interactions.

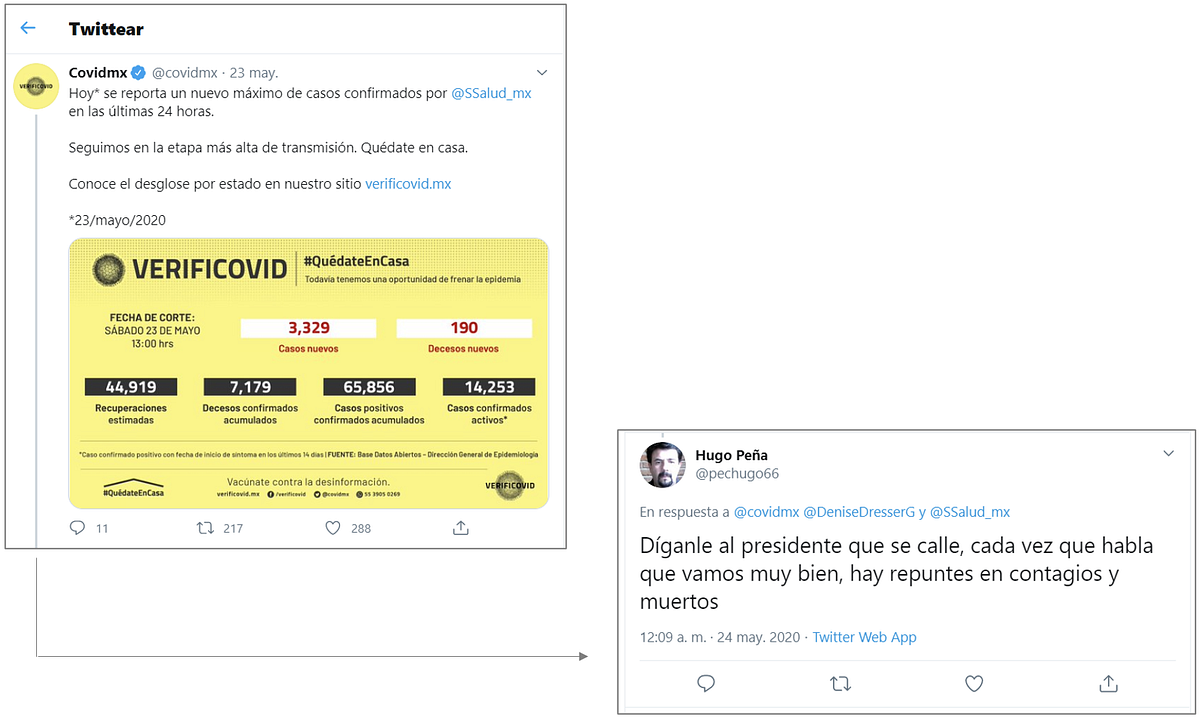

The audience tended to mention political actors and journalists together to call for news reporters to use their positions to tell the Mexican government how they should handle the pandemic.

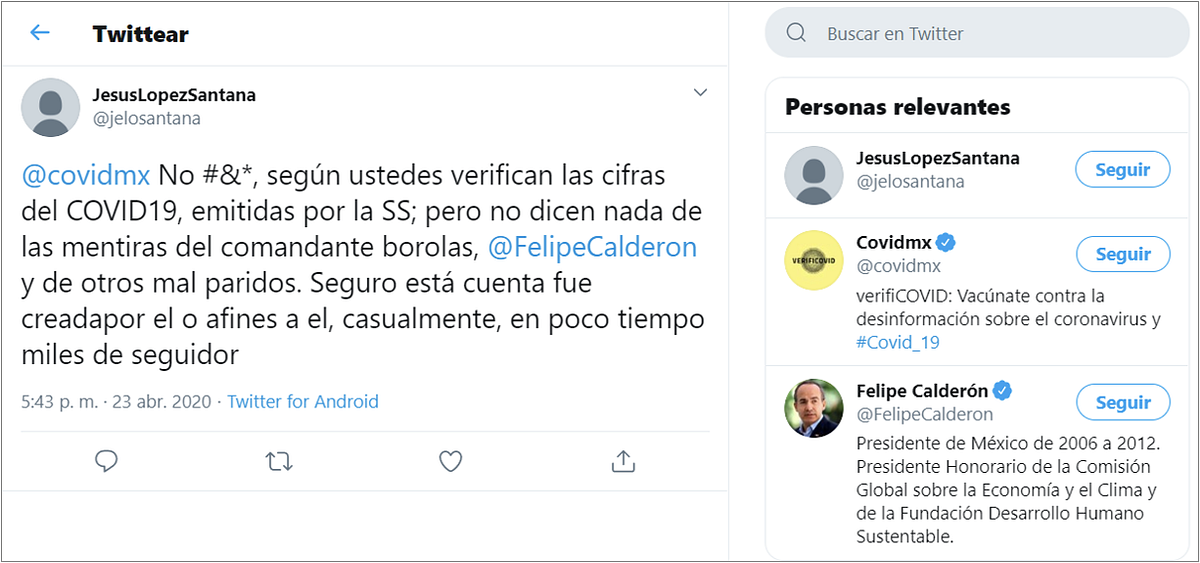

Political actors and @covidmx were surprisingly also mentioned together in what appeared to be political attacks. Some audience members accused @covidmx of working for ex-President Calderón, who opposes the current Mexican government.

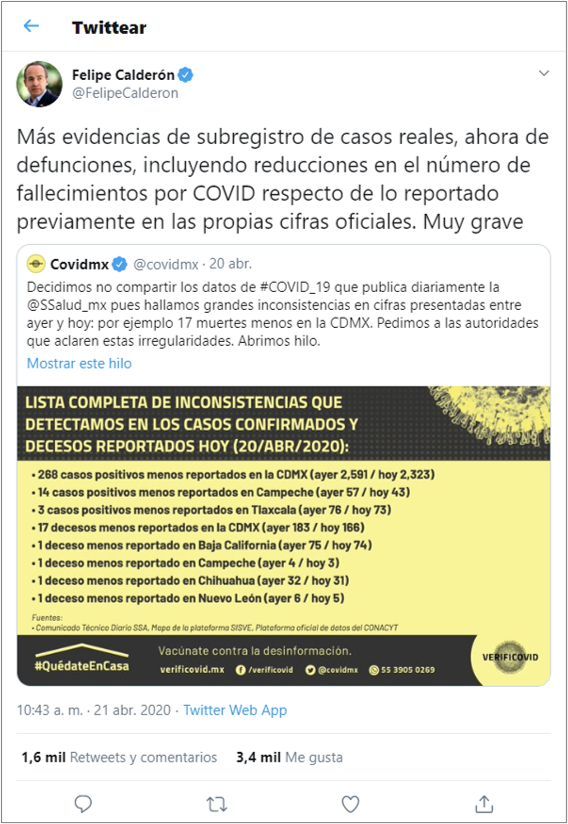

At one point, Calderón selectively decided to cite a tweet by @covidmx, marshalling it as evidence that the current government was underreporting the number of COVID-19 deaths in the country.

One could argue that the account of @FelipeCalderon acted selectively as the Mexican Federal Government acknowledged hours earlier to his tweet the mistake they made in their data collection and explained why they had erroneous numbers in their death toll. Yet, the ex-president did not mention the clarification. Additionally, Calderon’s tweets used language such as “muy grave” [very serious] to give a negative connotation to how the Mexican government is handling the pandemic.

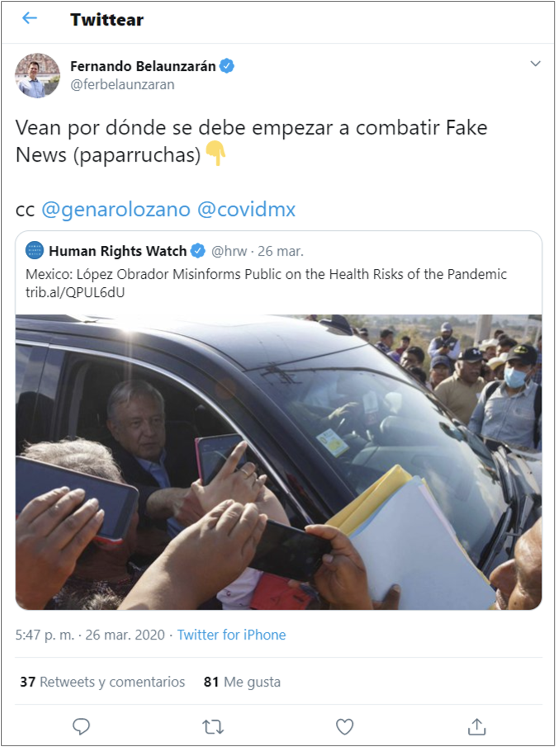

Some political influencers also selectively tagged @covidmx in tweets in which they attacked the current Mexican government.

Political influencers engaging with the fact-checking organizations appeared to hurt the organizations’ credibility in the eyes of some users, even when the organizations did not reciprocate that engagement.

Understanding the audience’s content

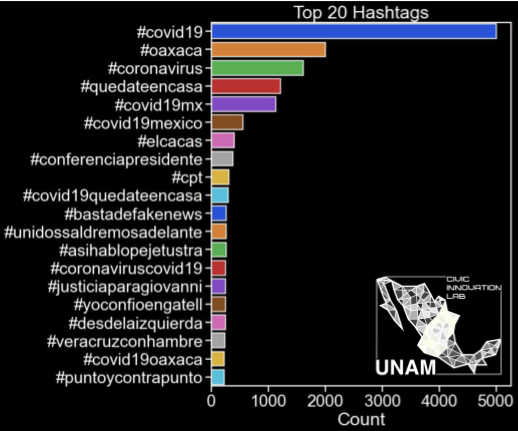

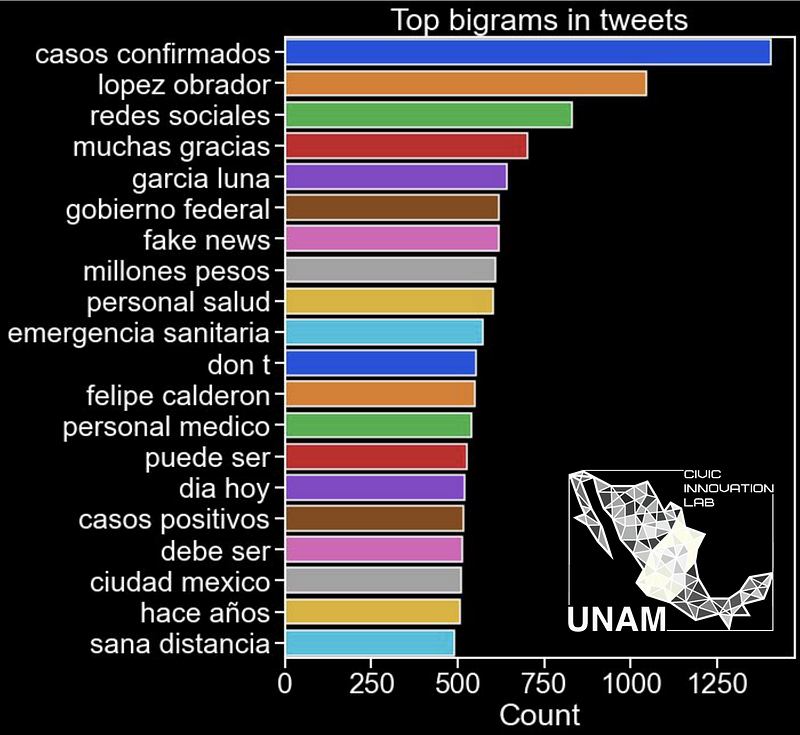

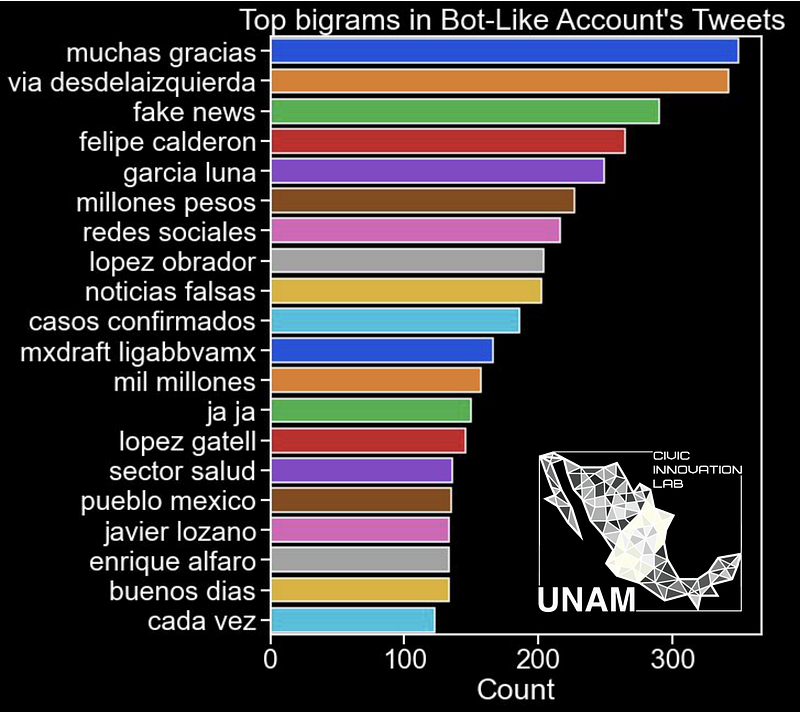

Researchers also identified the most common hashtags and “bigrams” used in audience tweets. Bigrams are pair of words — e.g., “fake news” — that tend to appear together in the text corpus.

The most frequent hashtags that the audience used included #COVID-19, #Coronavirus, #QuedateEnCasa (“stay home”), #YoConfioEnGatell (“I trust Gatell,” the main health spokesperson in Mexico), #JuntosSomosMasFuertes (“We are stronger together”), and #BastaDeFakeNews (“Enough of fake news”).

The audience also tended to employ more overtly political hashtags such as #ElCacas (a pejorative nickname used for current Mexican President Obrador) or #AsíHablóPejetustra (a phrase used to mock anything that President Obrador says). Another popular hashtag that the audience used was #JusticiaParaGiovanni, which related to social justice and police brutality after the Mexican police killed a man who had refused to wear a mask.

The most-used bigrams were also about COVID-19 and fact-checking, e.g., “casos confirmados” (“confirmed cases”) and “personal salud,” (“healthcare workers”). However, there were also bigrams focused on political actors, including Calderón and Garcia Luna, a former secretary of public security during Calderón’s administration who is currently under arrest in the United States for crimes involving connections to Mexican drug cartels. People questioned why @covidmx did not discuss the arrest of Garcia Luna, again questioning whether @covidMX was a politically neutral fact-checking organization

Audiences with bot-like behavior

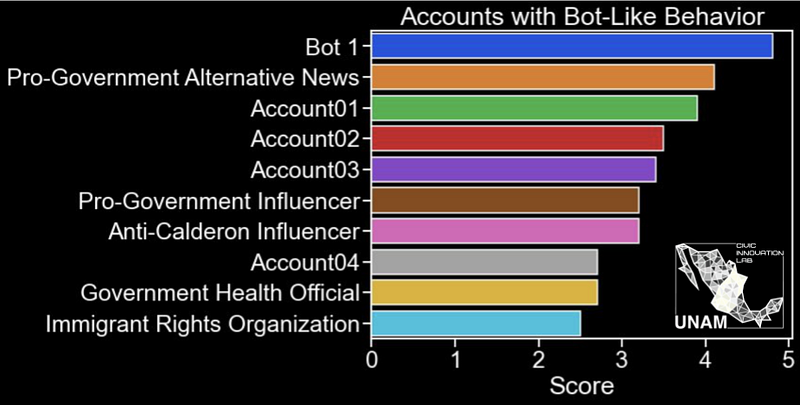

To further understand whether the fact-checking organizations had audience members displaying bot-like activity, this investigation used scores based on the Botometer platform, which gives each account a rating between zero and five based on the likelihood of whether an account is automated. While Botometer is not conclusive, it can serve as a starting point for further analysis.

The charts below shows audience accounts with Botometer scores that were greater or equal to 2.5, denoting that they might display some behaviors that appear to be more automated than human. Based on the profiles and tweets made by these audience members, at least four main types of audience members likely employed some form of automation: (1) journalist influencers; (2) political influencers; (3) nongovernmental organizations; and (4) “everyday citizens.” None of these audience members openly stated they were bots.

In the case of the journalists and NGOs, they likely used automation to ease some of the labor from their volunteers and human operators. The UNAM Civic Innovation Lab has studied in the past how bots can be used for social good to help NGOs and journalists.

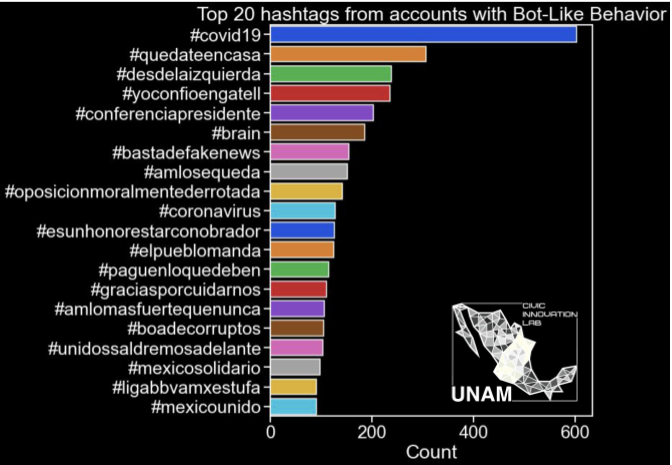

The top hashtags and bigrams used by these bot-like audience members were again related to health issues and combatting health-related misinformation, such as the use of the phrase “fake news.” In other instances, the accounts used hashtags and bigrams related to jokes, games, and winning raffles, such as #ligabbvamxestufa, and “ja ja” (a common interjection expressing laughter). This behavior resembles some of the tactics political trolls use to keep themselves and their audience entertained.

Implications

The analysis uncovered that both fact-checking organizations, @covidmx and @esp_covid19, had an audience engaging with their content, but @covidmx was much more frequently connected to a broader set of actors. However, these connections were not always positive: the main influencers who engaged with @covidmx were not related to public health but, rather, political influencers with their own agenda.

These accounts occasionally marshaled content from @covidmx to attack their political enemies. Former Mexican President Felipe Calderón, for example, cited tweets from @covidmx as the basis for his claims that the current Mexican government was underreporting the actual death toll from COVID-19. Calderón’s tweets were then used by other Twitter accounts to discredit @covidmx’s work and call into question the organization’s objectivity.

Initiatives to combat disinformation and misinformation, including fact-checking, sometimes have unintended second-order effects. In this case, an impartial fact-checking effort was at times exploited to advance political objectives. Those tweets and posts started to sow doubt about the trustworthiness and objectivity of, in this case, two fact-checking organizations that were providing timely, authoritative health information.

Saiph Savage is the co-director of the UNAM Civic Innovation Lab and HCI Lab at WVU.

Claudia Flores Saviaga is a researcher at the HCI lab at WVU and Facebook Research Fellow.

Rafael Morales is a researcher at the UNAM Civic Innovation Lab.

Esteban Ponce de León is a Research Assistant, Latin America, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.