Activists use Telegram to coordinate Belarus protests

How protesters openly coordinate peaceful rallies

Activists use Telegram to coordinate Belarus protests

How protesters openly coordinate peaceful rallies on the messaging platform

The coordination of demonstrations against the self-proclaimed Belarus President Alyaksandr Lukashenka are being conducted openly via public Telegram channels in Belarus. Some of these channels were launched in direct response to the violent oppression of protesters following the election, while others’ online history predate the vote. The peaceful nature of demonstrations coordinated via the public channels contrast with Lukashenka’s aggressive response, drawing additional spotlight to his attempt to protect his regime at any cost.

According to the final results announced by the Central Election Committee of Belarus on August 14, Lukashenka received 80.1 percent of the votes to Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya’s 10.1 percent. The lopsided election results, and the Belarusian people’s distrust in their veracity, has led to ongoing protests around the country. One of their main demands is to have new, fair elections, a demand that Lukashenka quickly dismissed. The situation has also led the European Union’s decision not to recognize Lukashenka as president of Belarus. Lukashenka, meanwhile, publicly stated the protests are the result of foreign interference rather than the actual will of the people.

NEXTA’s efforts

The highest-profile Telegram channel used to coordinate daily protests in Belarus is NEXTA Live. With over 2.15 million subscribers, it is biggest Telegram news channel in Belarus. In the wake of the internet slowdown on election day, Telegram became the central communication channel for Belarusians as social media platforms became less accessible.

The creator of NEXTA Live channel is Stepan Svetlov, a 22-year-old Lukashenka critic currently based in Poland. He told the Russian-language version of Delfi Lithuania that NEXTA’s newsroom consists of six people and receives 200 Telegram messages a minute. NEXTA’s team then verifies the content and publishes updates every five minutes. Telegram users submit their updates to NEXTA Live via @nextamail_bot Telegram bot.

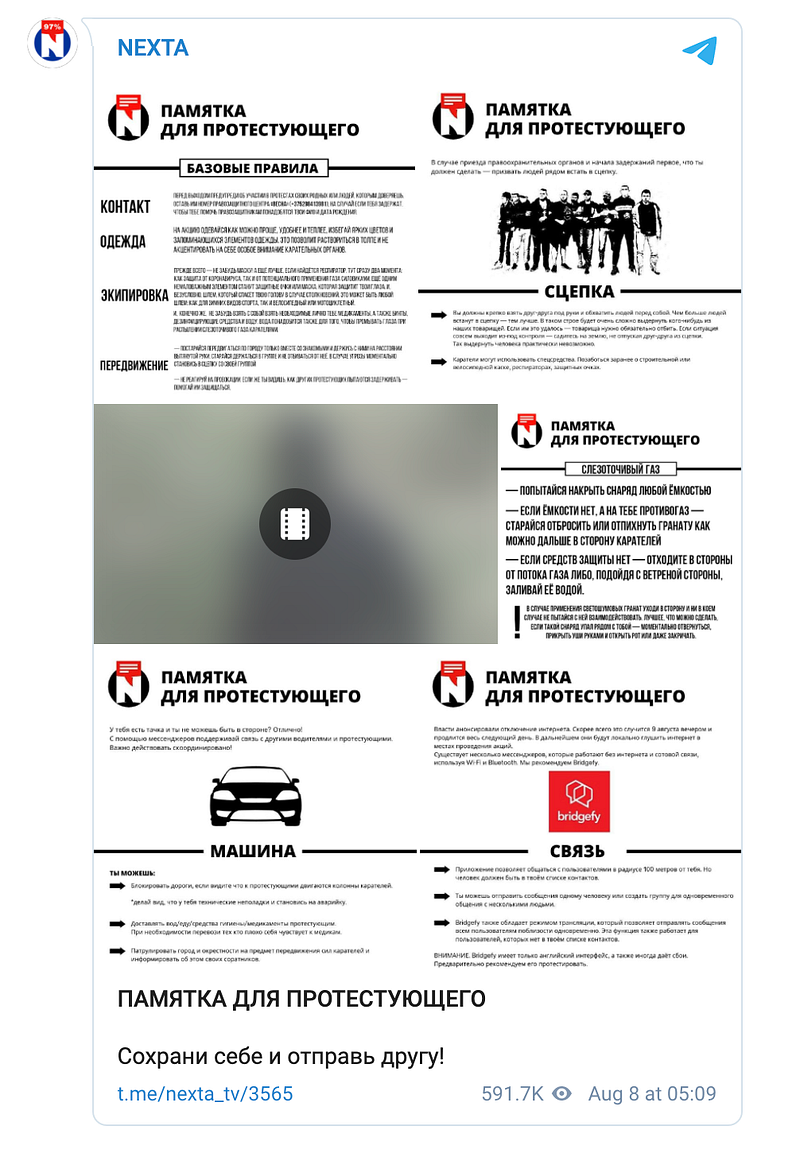

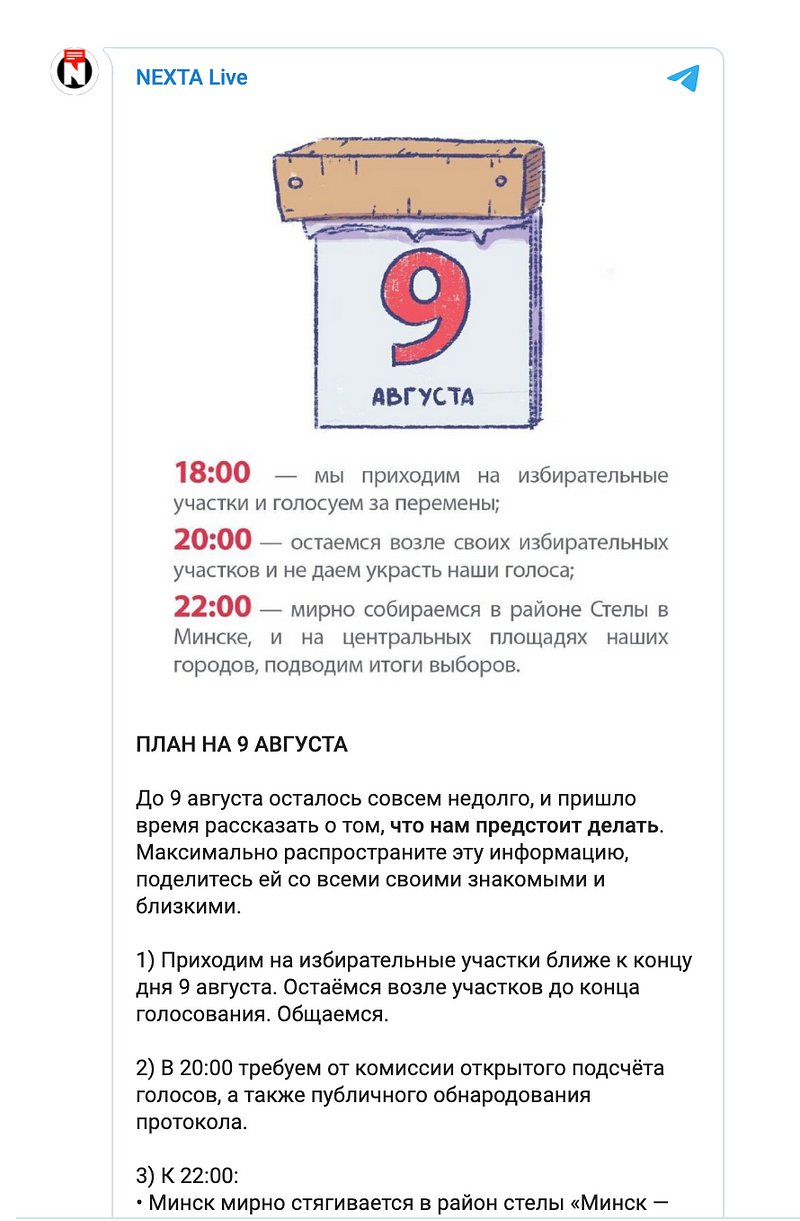

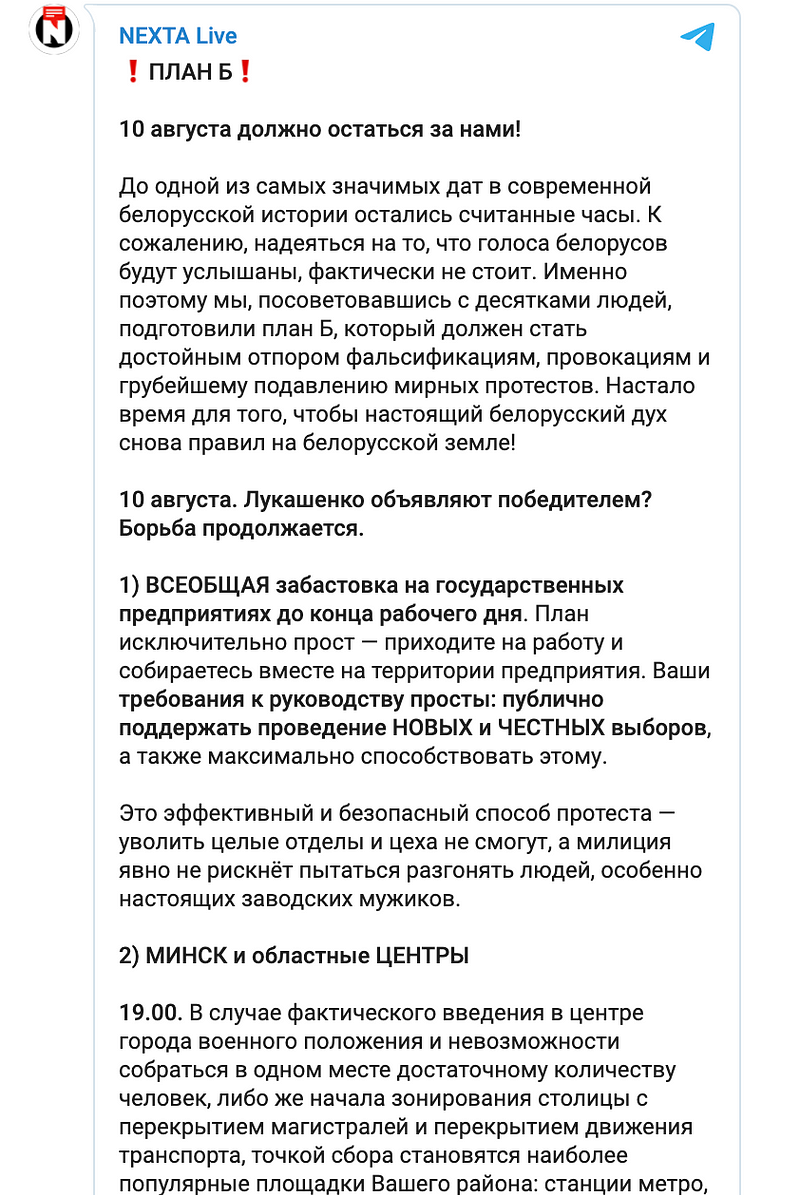

While NEXTA positions itself as a channel for “operational and exclusive news in Belarus,” on August 8, the day before the presidential election, the channel posted “Plan for 9 August,” (seen by 236,400 users) “Plan B,” (252,900 users) and “Instructions for a protester” (seen by 590,900 users). These documents shared logistics information for protesters, including contact information for the Belarus human rights organization Vesna; briefings on what to wear and how to behave in a crowd; recommendations on how to make human chains; instructions for car drivers on how to help by blocking roads and providing water supplies to protesters; and details on how to use the offline Bluetooth communication platform Bridgefy to share relevant information with people nearby.

The general plan for election day called people to come to election precincts “closer to the end of the day” then stay there until 8pm to request election tallies. At 10pm, they were instructed to go to Minsk’s Hero City Square; if it was blocked, they were to go to Nezavisimosti Avenue or Pobiditeley Avenue instead.

On election day, people saw long lines by 2pm that afternoon. The call for people to come by the end of the constituency office hours most likely intended to keep people on the streets after the precincts close. People indeed stayed by the precincts later relocated Hero City Square.

The “Plan B” document published by NEXTA Live called for a nationwide strike of state enterprises; instructed people what to do in case the most popular gathering spots in Minsk and elsewhere were blocked by state police; and encouraged people in other regions to “go to local governances and demand local administrations to join the protest.”

On August 14, opposition candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya thanked workers of state-owned enterprises for joining the strike, apparently backing NEXTA’s initiative. No operational information was shared on Tsikhanouskaya’s official Telegram channel regarding the protests. Contrary to NEXTA’s call to come to constituencies later in the day, Tsikhanouskaya called to come and vote as early as possible and shared other instructions on voting procedures. This would suggest that Tsikhanouskaya did not openly coordinate with NEXTA.

Tactical briefs for protesters

Revolucionnoe Deystviye, an organization of Belarussian anarchists, criticized NEXTA’s initial plan to gather at Hero City Square, as it would be easy for OMON — Belarusian police special forces — to block the space and crack down on protesters. The anarchists, however, endorsed the “Plan B” document, which was more decentralized. On August 9 they shared a compilation of eight Telegram posts that instructed protesters on how to make human chains (relying on a NEXTA video from the initial protest document); how to block a road; how to avoid fabricated criminal charges and police abuse; and how to protect oneself during protests, among other tactical recommendations. The compilation of resources garnered 20,100 views on Telegram.

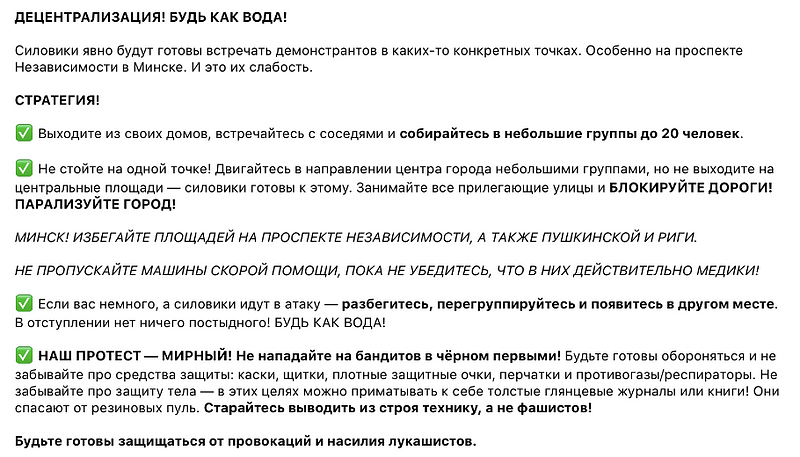

On August 11, the day after a series of violent detentions by police, NEXTA Live posted a new strategy document to decentralize and “be like water.” The post briefed protesters to gather in small groups of 20 people then move to the city center, avoiding big streets where OMON forces would likely be stationed. If OMON attacked, protesters were encouraged to spread out and regroup in other places. The post also recommended not to attack members of OMON, but to target their vehicles. The August 11 strategy document raises the possibility that NEXTA took into account suggestions by Revolucionnoe Deystviye, but their public communications have not implied any direct coordination.

Help for the detained and their families

After reports of police violence and torture at the Okrestino detention center on the night of August 10–11, volunteers from the Belarus Red Cross provided medical help and organized the collection of hygiene kits for those who had been detained. The Union of Minsk Lawyers, meanwhile, offered free legal help for those who were detained illegally.

On August 12, the Telegram channel Okrestina spiski (“Okrestino Lists”) was created. It shared lists of people who had been released from the detention center. The channel soon grew into a centralized coordination channel for people who wanted to find missing persons, provide help for the detained, or chat with others in similar circumstances. The channel’s pinned message leads to an extensive Google document that lists resources for finding people, medical and psychological care, and legal assistance. The document features lists of volunteer doctors, psychologists and lawyers.

Additionally, the Telegram channel Karateli Belarusii (“Belarus Punishers”) was created on August 11, with an intention to track “names, addresses and relatives” of law enforcement individuals who allegedly abused protesters the night of August 10. Telegram users can report screenshots with evidence to private chats listed on the channel. In response to this initiative, Lukashenka warned users of the channel, “Don’t do it. Do not play with fire. Our military have enough resources to protect themselves, their families and maintain national security.”

Grassroots activities during the protests

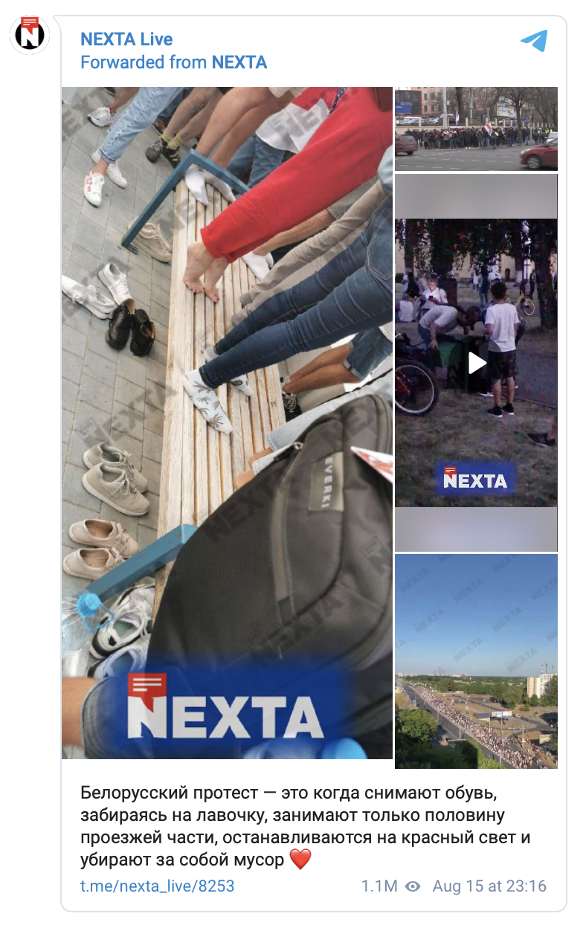

On August 16, about 200,000 protesters gathered in Minsk, according to independent Belarus media outlet Tut.b, which used the tool Mapchecking for crowd measurement. Protesters demonstrated very peacefully, collecting trash and taking off their shoes when standing on a bench, as well as leaving enough room on the streets for regular cars to pass by.

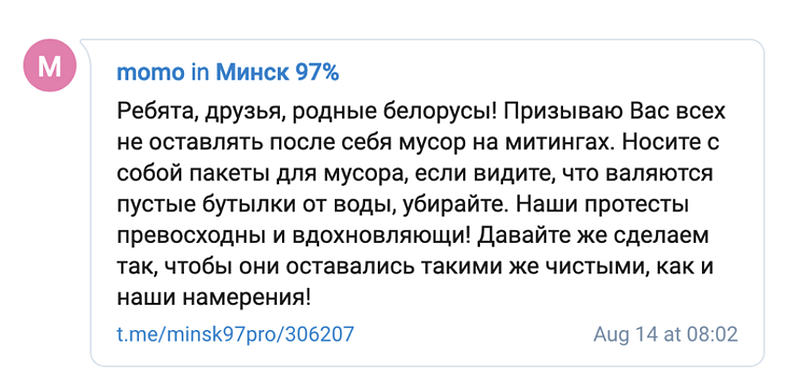

The idea to collect trash was suggested by a few anonymous Telegram users on the public Telegram chat Minsk 97%. In one announcement, they wrote:

Guys, let’s start cleaning the city tomorrow. Let’s collect trash, put things back on places and let’s fix what’s broken. Let’s show that we can create something, not only stand, wave and beep. Otherwise regular people who are watching us will not support us, because they will see us as bullies. Mass improvement of city environment, and cleaning — a protest to violence and rout. If you support this idea, then share it massively to attract attention. Belarus is shocked! Share news.

Amid an ongoing crackdown on press freedom and allegations that Belarusian authorities were throttling internet connectivity, Telegram has emerged as a crucial resource for those watching the ongoing developments in Belarus as well as those coordinating protests. The app, whose co-owner, Pavel Durov, claimed on Twitter had implemented “anti-censorship tools” in anticipation of the internet lockdown in Belarus, was reportedly one of the only useable apps amid the lockdown.

Nika Aleksejeva is a Research Associate, Baltics, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.