South African Twitter users misattributed as fake Chinese accounts

A Twitter thread incorrectly identified South

South African Twitter users misattributed as fake Chinese accounts

A Twitter thread incorrectly identified South African Twitter users as fake pro-Chinese Communist Party accounts that ostensibly lobbied for a COVID lockdown

A Twitter thread on August 21, 2020 claimed that South African President Cyril Ramaphosa’s Twitter account was targeted by scores of fake pro-Chinese Communist Party Twitter accounts in March 2020. According to the thread, these accounts demanded South Africa enter a total lockdown in reaction to COVID-19. President Ramaphosa formally announced South Africa’s lockdown the next day.

The claims were quickly amplified by anti-lockdown activists, some of whom argued that the thread proved South Africa’s lockdown was motivated by Chinese propaganda rather than science. Nick Hudson, a staunch anti-lockdown campaigner, stated that several of the accounts he looked at were “indeed the divisive and pro-Chinese cesspools described.”

But even a cursory examination of these accounts shows that there is no basis for these claims. Only one of the 25 accounts listed in the thread appears to tweet pro-Chinese content with any frequency; even in that particular case, the account appears to be a genuine South African. None of these accounts exhibits any indicators that would flag it as a Chinese disinformation operation. In fact, the indications are that all of these accounts are real South Africans, displaying specific local knowledge and using vernacular languages. At least one of these accounts is an identifiable South African individual.

Misattribution of disinformation campaigns erodes trust in institutions that are actively investigating and researching such campaigns, and also gives real perpetrators a free pass. In other cases, such as this situation, innocent individuals are labeled as bots or sockpuppet accounts.

OSINT vs BULLSINT

The thread by Twitter user @MichaelPSenger was created on June 11, 2020, and consists of a long-running series of articles, links and tweets that take a very pointed aim at the CCP and its activities online. Rather than having a conventional Twitter bio, @MichaelPSenger’s bio states, “COVID lockdowns are not science, they’re CCP propaganda.” It references that he is from the United States and includes a #StandWithHongKong hashtag. The account shared links to the New York Times’ coverage of Twitter’s takedown of a Chinese-linked disinformation network which seems to be used as the basis for his claims.

On August 10, 2020, @MichaelPSenger began posting collated screenshots of “CCP’s army of fake accounts” that he supposedly identified. These “CCP accounts” were found in replies to tweets by South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem, Gov. Dan Andrews of Victoria in Australia, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Senger, whose LinkedIn profile describes him as an attorney formerly employed by a law firm in Atlanta, GA, didn’t indicate the methodology used to determine that the South African Twitter accounts were attributable to the CCP, and it is unclear how they were identified and distinguished from regular users. (The DFRLab reached out to Senger for comment; as of the time of publishing, he had not submitted a response.)

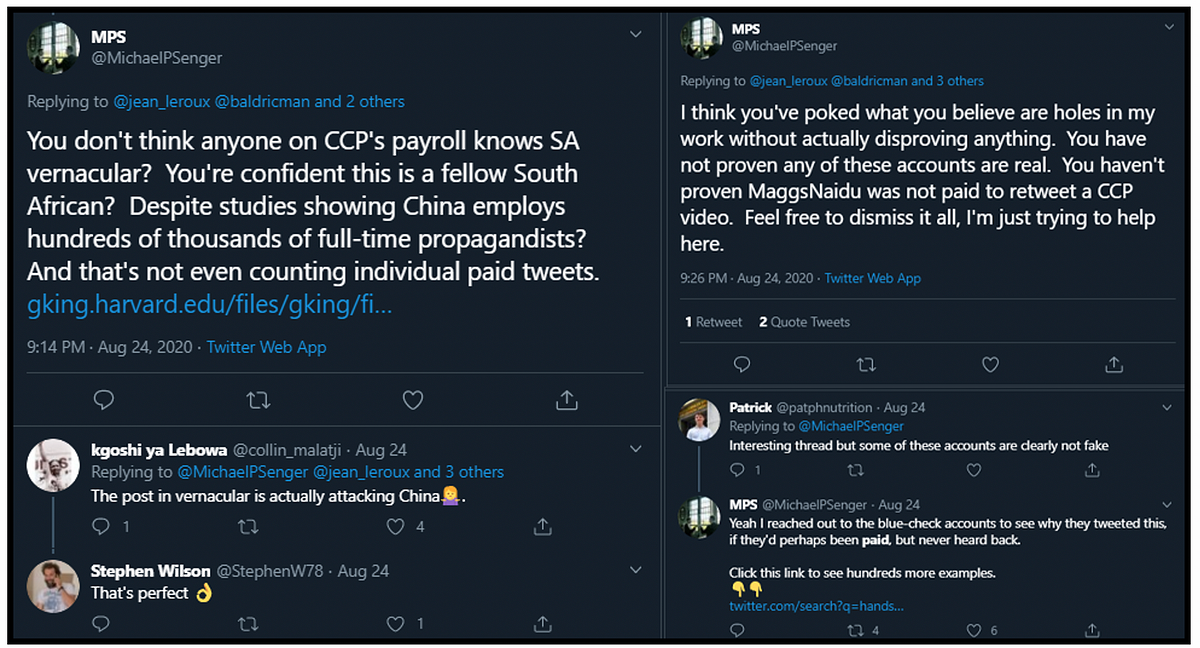

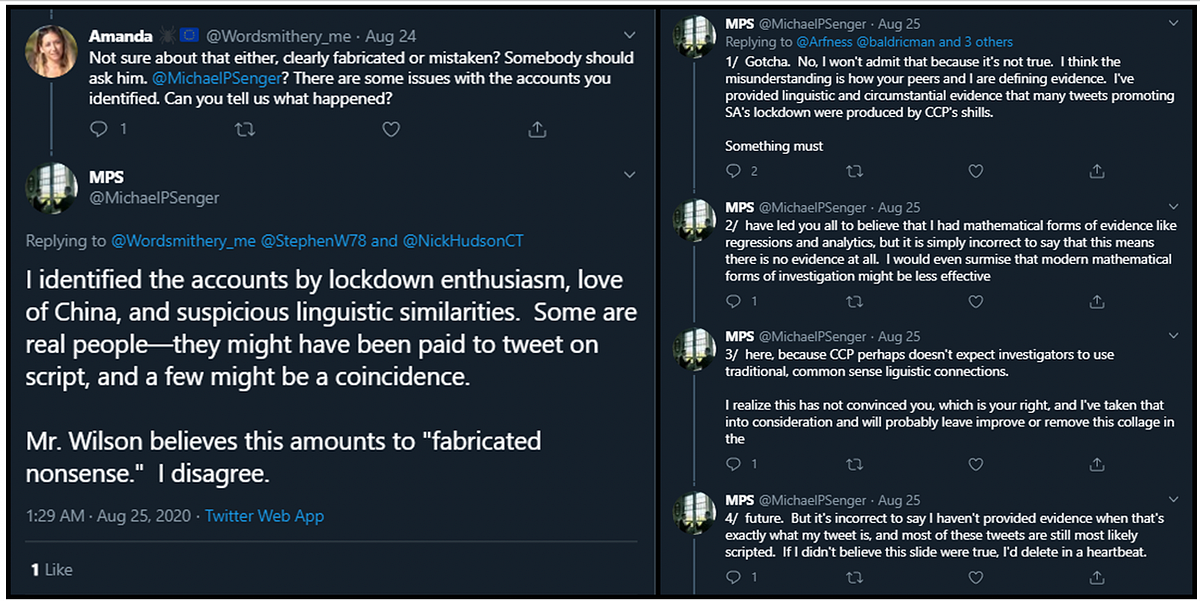

When challenged on his conclusions by other Twittter users, Senger indicated that he identified these accounts by “lockdown enthusiasm, love of China and suspicious linguistic similarities.” Considering that Senger is a staunch anti-lockdown campaigner according to his Facebook profile, it appears Senger conducted his investigation with a conclusion already in mind.

China cleaning up SA?

This is evident since the South African cohort of “CCP accounts” he identified misses the mark on several fronts. If this were indeed a CCP operation, the network is highly sophisticated and targeted towards South African audiences. Even then, these “fake accounts” displayed several very South African characteristics.

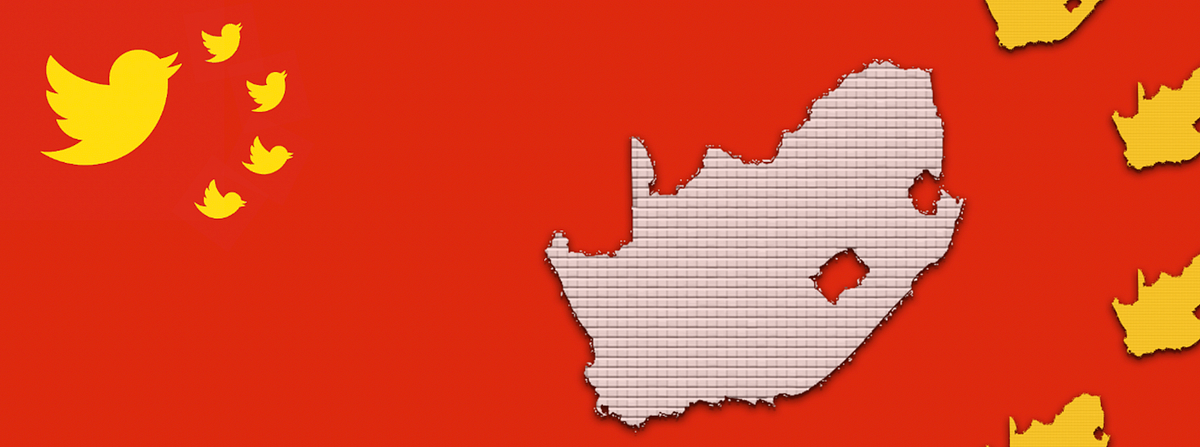

For example, most of the accounts he listed showed an extensive localized knowledge of South Africa, including hyperlocal knowledge of streets, shopping centers and suburbs. A number of the accounts used South African slang and vernacular language, and displayed distinctly South African mannerisms.

In at least two cases, accounts Senger labeled as fake CCP accounts lodged a customer service complaint via Twitter: one with a local municipality regarding a faulty powerline, and another with a local retail shopping group regarding refuse in its vicinity.

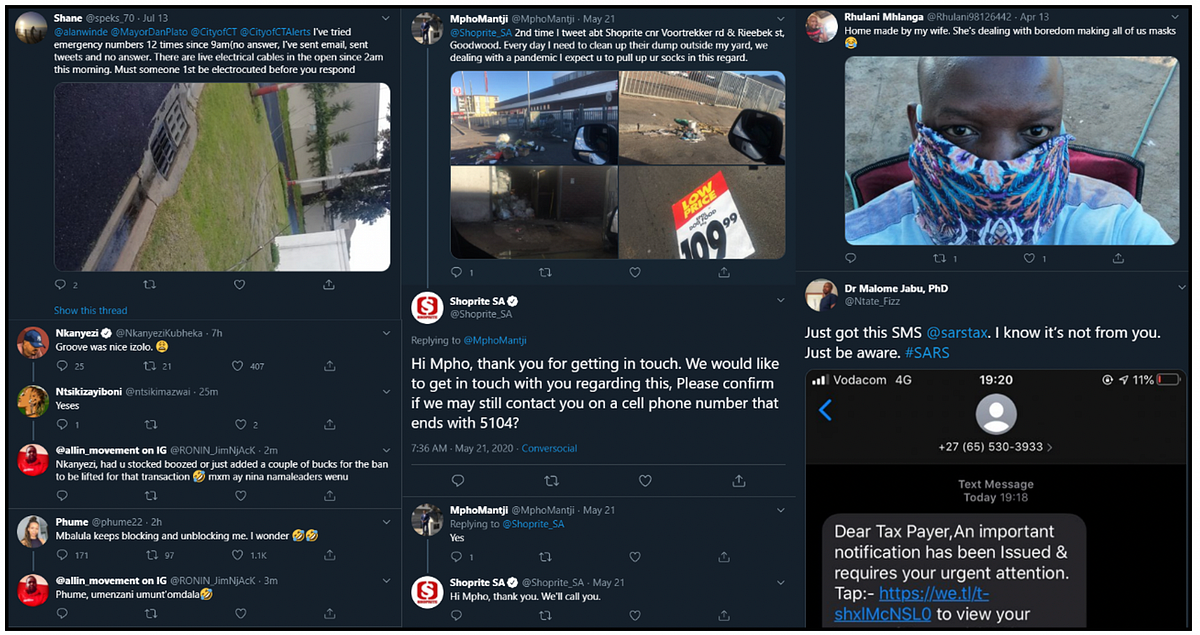

At least two of the accounts posted screenshots on their timelines revealing South African mobile network carriers Telkom and Vodacom in the signal bar of their phone screen, while a third correctly identified a phishing SMS ostensibly from the South African Revenue Service.

One of the accounts Senger attributed to the CCP is a well-known South African personality, Maggs Naidu, who is a very real South African. Naidu responded to Senger directly and denied that he is, or was, a fake account posting scripted tweets.

Doubling Down

When confronted with these incongruencies, Senger doubled down on his conclusions, but now added that these accounts could have been paid to tweet on behalf of the CCP. He provided no proof for these claims.

As other South Africans pressed him to provide evidence of this, Senger provided some insight into how he arrived at his conclusions.

Attributing disinformation networks to specific state actors is a difficult enough endeavor when one can show coordinated behavior among the accounts begin investigated. The accounts he listed presented no such coordination.

In addition, to claim pro-lockdown accounts were paid to do so, in the absence of any form of evidence, amounts to the spread of disinformation.

Digging Deeper

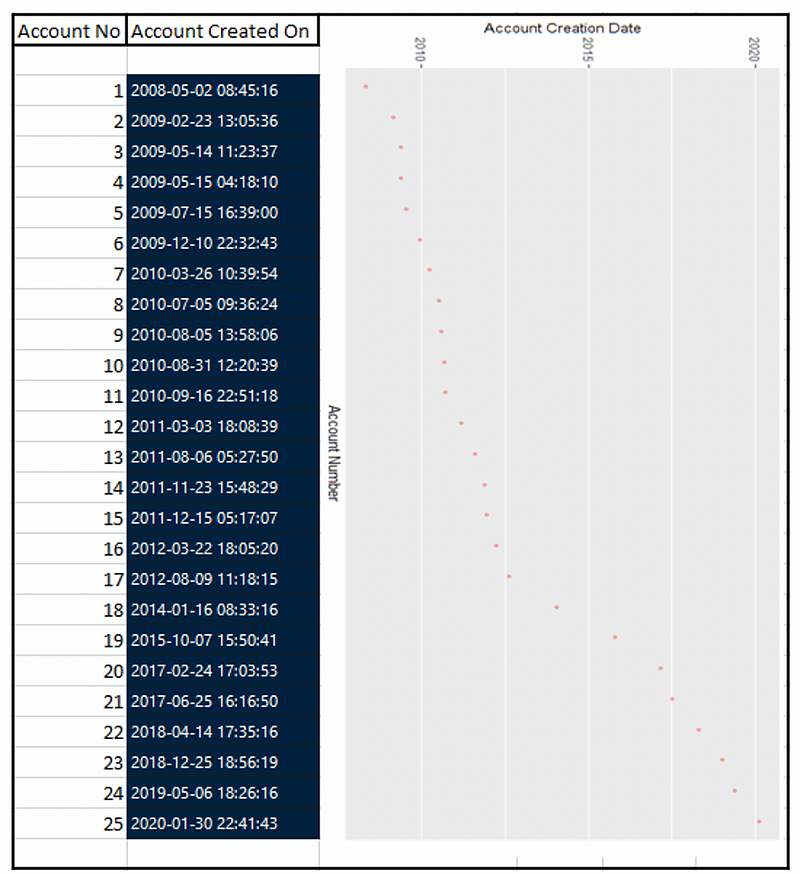

The DFRLab further investigated the accounts identified by Senger to see if there was a connection between them that wasn’t apparent on the surface. Using the Twitter API, we extracted the account information for each of these 25 accounts. This allowed us to analyze information such as creation dates, frequently used hashtags, and mentions — all useful indicators of whether an account is conducting itself suspiciously.

None of the accounts featured default profile pictures or random alphanumerics in their user handles, which can be indicators of suspicious activity, albeit weak ones in isolation and are only ever used in conjunction with other evidence of coordinated activity. The accounts also only tweeted in English or vernacular South African languages, whereas for coordinated networks the accounts are often language agnostic.

The account creation dates also revealed no patterns that suggests the accounts were created en masse, as only two accounts were created on the same day, and even then more than 12 hours apart.

Granted, this analysis was conducted on a very small sample, but in the absence of a clear indication of Sanger’s methodology, these are the only accounts available for analysis.

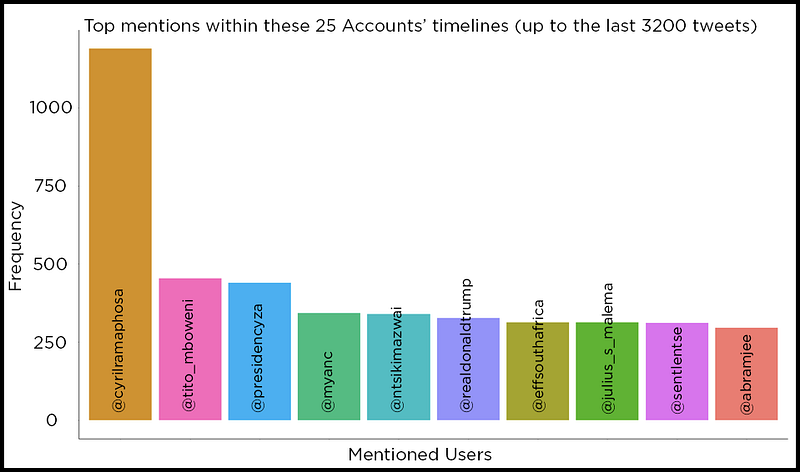

The Twitter API was also used to extract the most recent 3,200 tweets (or less, if the account had not tweeted that much) for each of these accounts. This provided a total of 49,492 tweets made by the 25 accounts.

Among these tweets, the top mentioned Twitter account was President Cyril Ramaphosa, followed by Finance Minister Tito Mboweni, and the official account of the office of the South African presidency. Most of these mentions predate 2020, and nothing indicates that this is part of a coordinated attempt at pressuring the president into a lockdown.

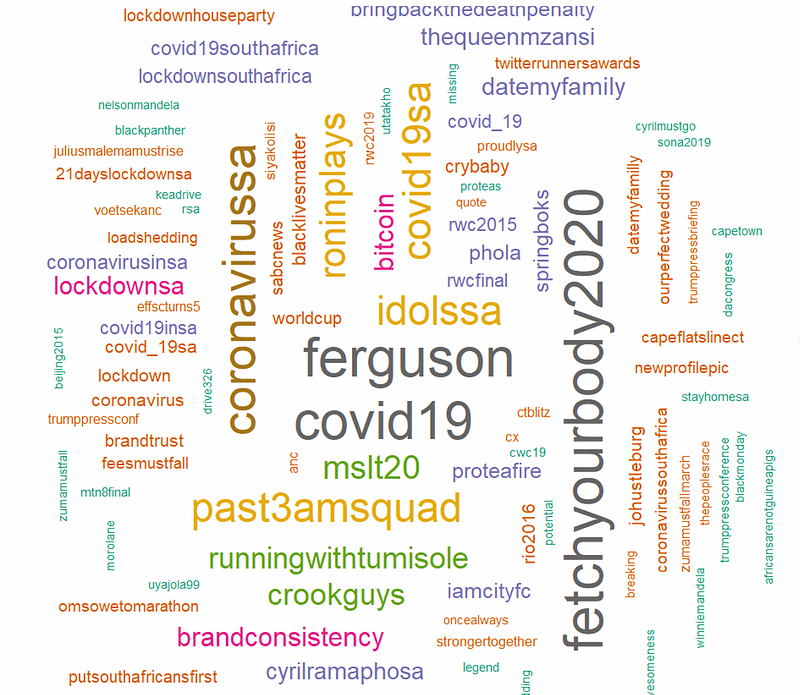

A word cloud of the 100 most frequently used hashtags among the 49,492 tweets reveals several spammy hashtags, but none of them are particularly pro-Chinese. The single China-related hashtag seen in this analysis was #beijing2015, used during the IAAF World Championships in Athletics held in Beijing five years previously. The use of this hashtag appears related to South African Wade Van Niekerk breaking the men’s 400m world record during the competition.

Keyword searches on the tweets sent by these accounts show that by and large the accounts did not display any pro-Chinese sentiments in their tweets. Only one of the 25 accounts was explicitly supportive of China. But support alone does not warrant classifying the account as a CCP sockpuppet: the user still used South African vernacular, and mostly tweeted about his day-trading exploits instead of China.

Of the more than 49,000 tweets we analyzed, only 230 mentioned “China” at all, and even then, it was often in the context of criticizing China.

Disinformation networks often use sockpuppet accounts meant to be perceived as something, or someone, else. But this also means that attribution needs to be based on stringent indicators that exclude a more reasonable hypothesis: in this case, instead of an organized CCP-backed disinformation network, an assortment of real South Africans, some of whom also support a lockdown during the pandemic.

Jean Le Roux is a Research Associate, Southern Africa, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab and is based in South Africa.

The DFRLab team in Cape Town works in partnership with Code for Africa.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.