Facebook removes inauthentic assets linked to the Philippine military

Pages targeted domestic audiences, engaging in

Facebook removes inauthentic assets linked to the Philippine military

Pages targeted domestic audiences, engaging in “red-tagging” of Duterte’s critics and supporting the controversial “anti-terrorism” bill

Editor’s note: This analysis and disclosure would not be possible without those targeted speaking up and working to #HoldTheLine in the Philippines. In particular, the independent newsroom Rappler has both investigated and been the target of this online network. Their most recent original reporting on this case can be found here and here.

On September 22, 2020, Facebook took down 31 pages and 77 Facebook and Instagram accounts it linked to individuals affiliated with the Philippine military for engaging in coordinated inauthentic behavior targeting domestic audiences in the Philippines.

In a statement provided to the DFRLab, Facebook said:

This operation appeared to have accelerated between 2019 and 2020. They posted in Filipino and English about local news and events including domestic politics, military activities against terrorism, the pending anti-terrorism bill, criticism of communism, youth activists and opposition, the Communist Party of the Philippines and its military wing the New People’s Army, and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines… our investigation found links to Philippine military and Philippine police.

The DFRLab had access to a subset of the assets — 23 pages, 42 Facebook user accounts, and 28 Instagram accounts — prior to their removal. These assets, the first of which were created as early as 2015, primarily posed as independent pages, posted anti-communist content demonizing leftist and youth organizations, engaged in the “red-tagging” of current President Rodrigo Duterte’s critics — the practice of branding opponents as communists and terrorists — and supported the Philippine government’s controversial anti-terrorism bill.

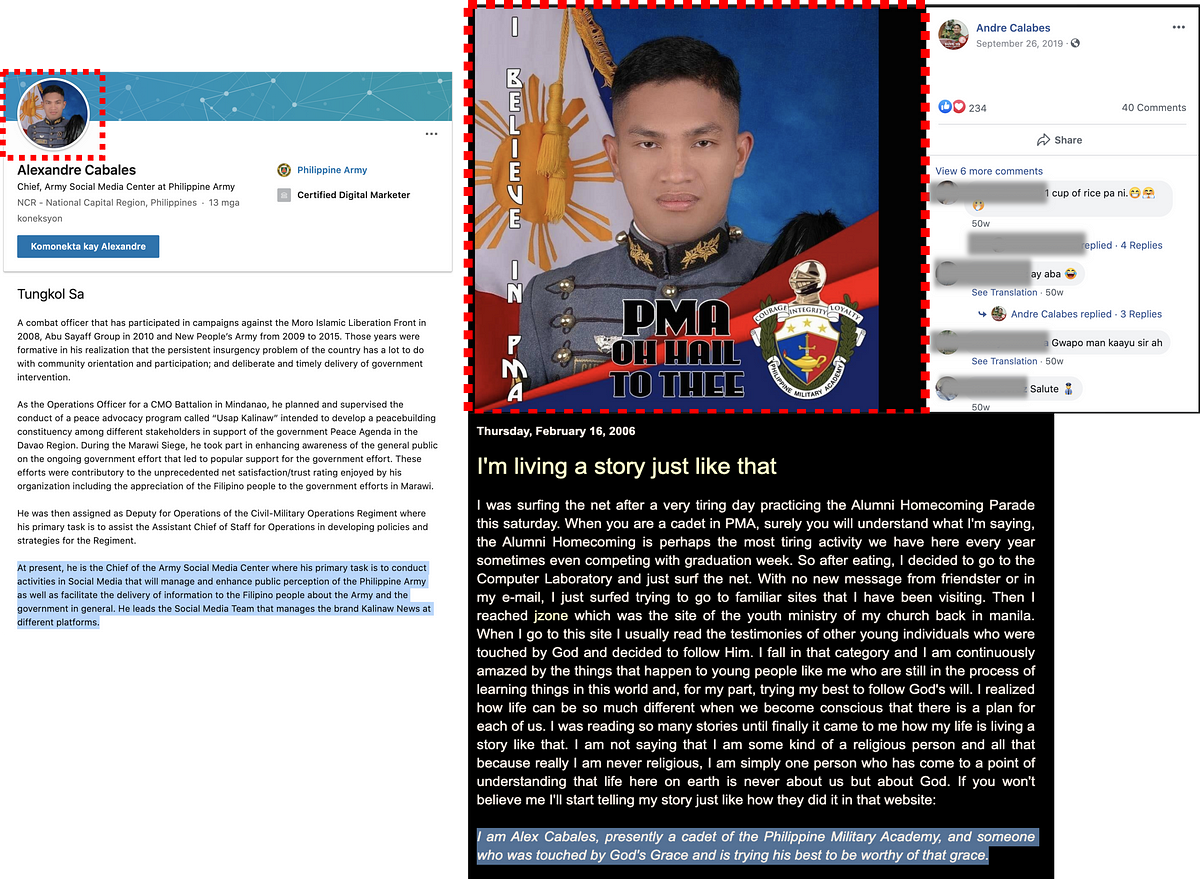

There was open-source evidence of coordination among some of the pages in the form of simultaneous posting; there was also evidence supporting Facebook’s attribution of this operation to individuals linked to the military. Multiple user accounts in the set belonged to individuals who appeared to be serving in the Philippine military, including, notably, Alexandre Cabales, Chief of the Army Social Media Center.

There was also evidence that several military-linked user accounts were coordinating social media campaigns in private Facebook groups, although the exact nature of what they were discussing within those groups could not be determined.

Facebook’s Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior policy focuses on the behavior of assets, not the content that they post. But the company has other policies that center on the potential for real-world violence and other offline harms, such as its policy against Violence and Incitement. While this network was removed for CIB, the content of this operation contributed to the assessment of possible harm. Local as well as international human rights organizations have accused the Duterte government of red-tagging, labeling Duterte critics as communist insurgents and even accusing them of terrorist recruitment.

The military, specifically, has been accused of coordinating these attacks online, which have the potential to incite offline violence. As a recent Human Rights Watch report on the coordinated harassment tactic noted, “the reality is that people who are red-tagged are at heightened risk, including of being targeted for killing.”

In one of the most egregious recent examples of red-tagging, two human rights activists, Randall Echanis and Zara Alvarez, were murdered in August 2020. “The murders of Alvarez and Echanis also show how the government’s new anti-terrorism law can be misused,” Human Rights Watch reported. “The Anti-Terrorism Council, the chief enforcer of the law, is empowered to designate individuals as terrorists.”

Background: a communist insurgency and the targeting of political activists

Since 1969, the Philippine government has battled a communist insurgency — the longest-running in Asia — led by the New People’s Army (NPA), the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CCP). The insurgency has outlived multiple Philippine administrations, including the dictatorship of former President Ferdinand Marcos, who ruled under martial law from 1972 to 1981 and dramatically expanded the powers of the military.

The CCP-NPA, which seeks the overthrow of the Philippine government, has continued to operate primarily in rural areas of the country, although internal divisions have weakened the organization considerably. Under current President Rodrigo Duterte, the Philippine government, as prior administrations had, initially engaged in peace talks with the CCP-NPA, but after the talks fell apart in November 2017, he labeled the group a terror organization and has since repeatedly called on the military to “destroy” it and other leftist organizations, including by proposing to form “death squads” to assassinate communist rebels.

Critics of Duterte, whose government has been widely denounced for extrajudicial killings in his brutal “war on drugs” and other human rights abuses, contend that his administration’s campaign against the communist rebellion is a political tool. On July 3, 2020, Duterte signed into law an anti-terrorism bill that would grant the government expansive powers to surveil and arrest suspected terrorists, under a broadly expanded definition of terrorism. The military is expected to use the law to go after the NPA, though human rights groups have raised alarm over the law’s potential to target political activists on the suspicion of being communist sympathizers.

The Duterte government, especially the military and its allies, have a track record of running online influence operations targeting their own people. Philippine news outlet Rappler has extensively documented these operations, which often incorporate coordinated harassment of political activists in the form of red-tagging.

Network summary statistics

Facebook pages

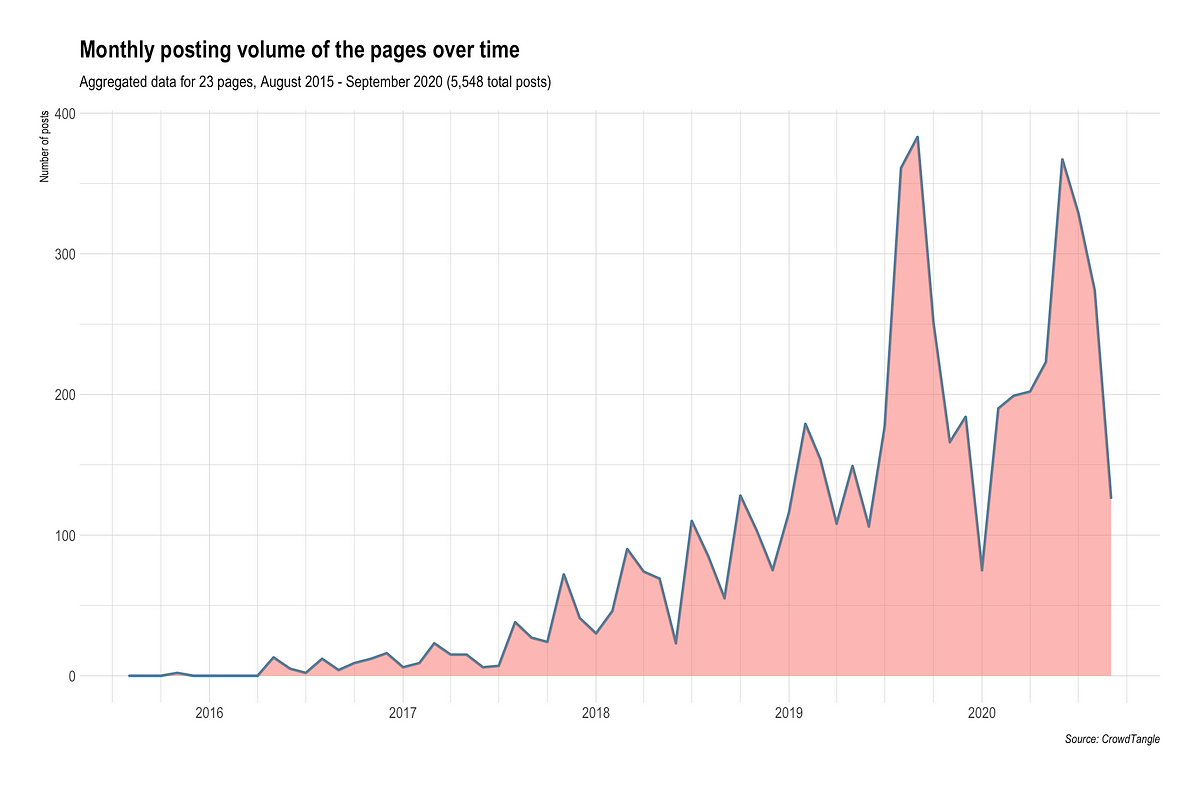

This was a long-running operation: the 23 pages in the network were created over a period of five years, from August 2015 to August 2020. Within that period of time, they posted 5,548 total posts — in Tagalog and English — with monthly posting frequency steadily increasing over time.

The pages varied vastly in audience size, ranging from about a dozen followers to tens of thousands, indicating that at least a portion of the network was fairly impactful.

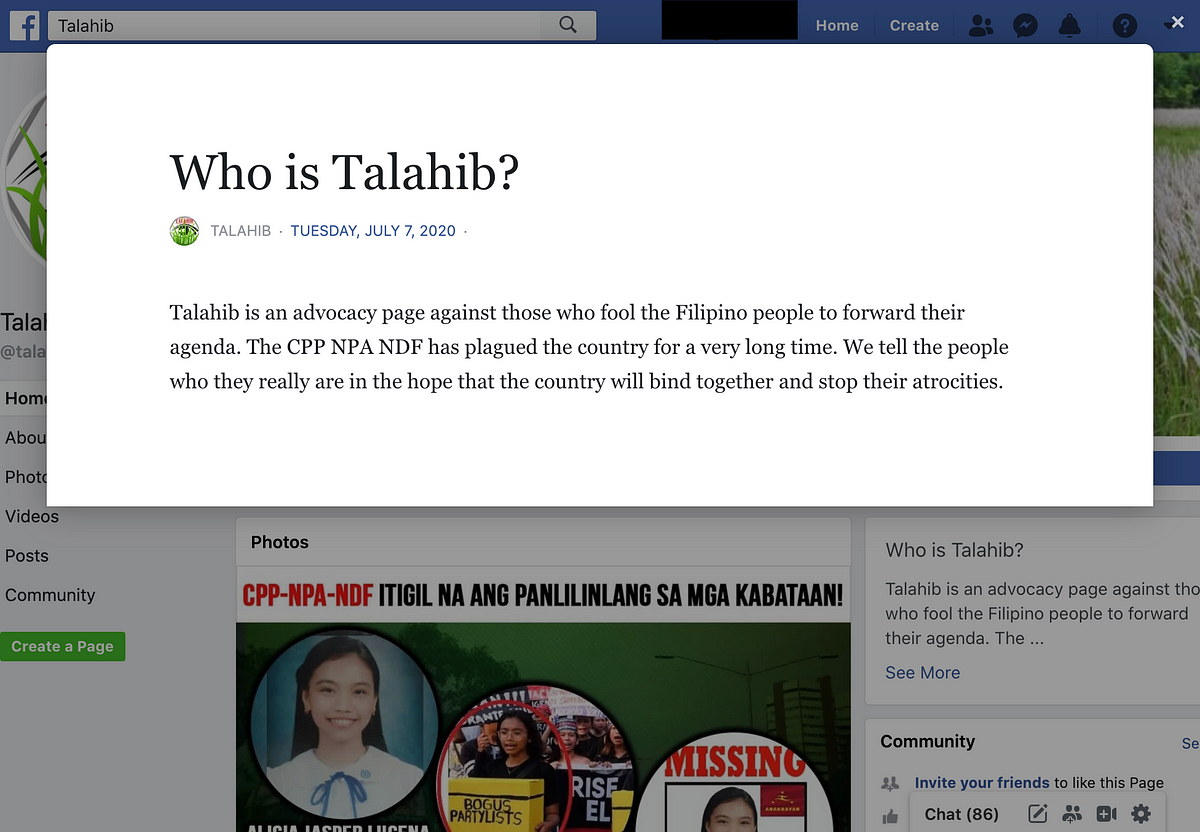

The largest page, “Talahib,” had 59,523 followers and garnered over half a million interactions by the time of removal. In its About section, the page described itself as an “advocacy page against those who fool the Filipino people to forward their agenda,” and stated it that it tells the people who the CCP-NPA “really are in the hope that the country will bind together and stop their atrocities.” The page offered no information on its operators.

This network relied heavily on visual media. The majority of posts across the pages — roughly 77 percent — were photos, followed by videos (14.25 percent). Over a five-year period, the 374 videos posted by these pages garnered 25 million views, about 10 million of which were directly from the pages’ posts.

Key themes

The main theme across the pages was anti-CCP-NPA content: they posted about the CCP-NPA’s alleged recruitment of children as armed combatants, supported Duterte’s controversial anti-terrorism bill, and red-tagged progressive politicians and activists as communist terrorists.

Hands Off Our Children movement

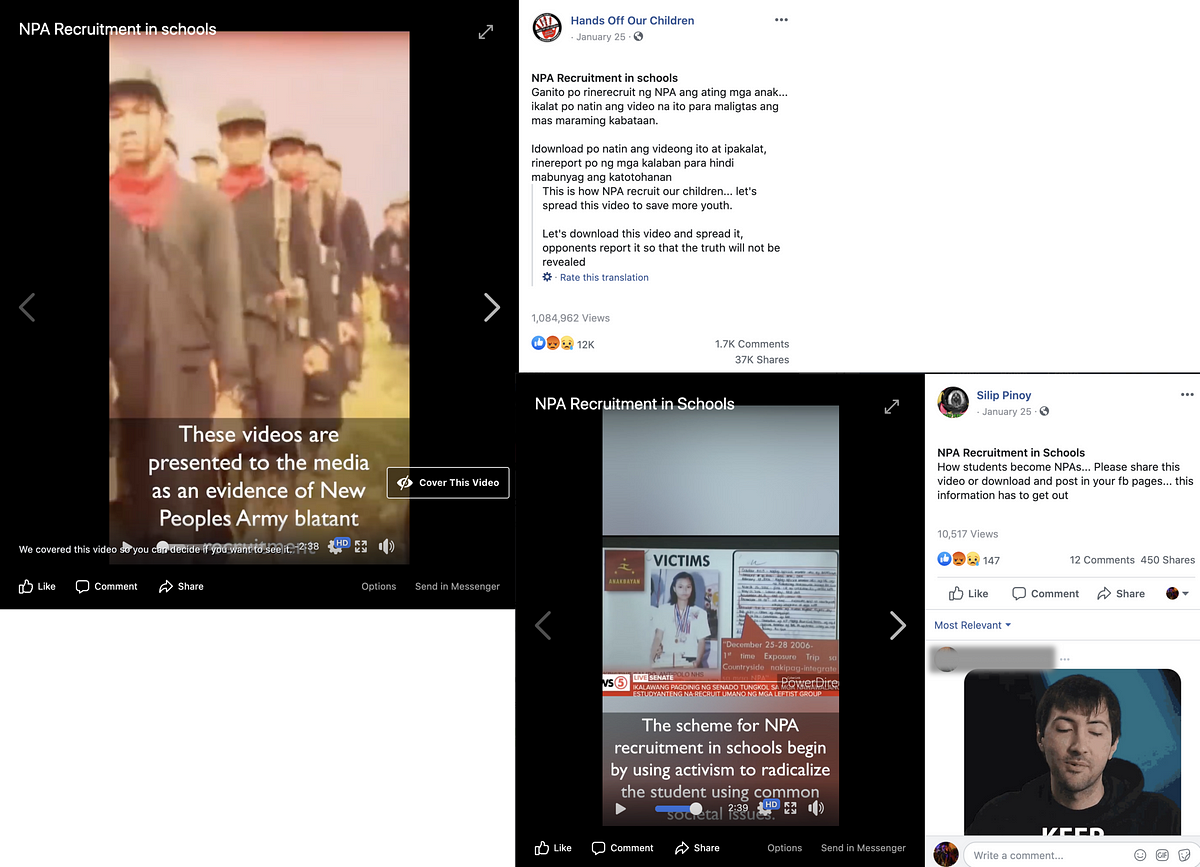

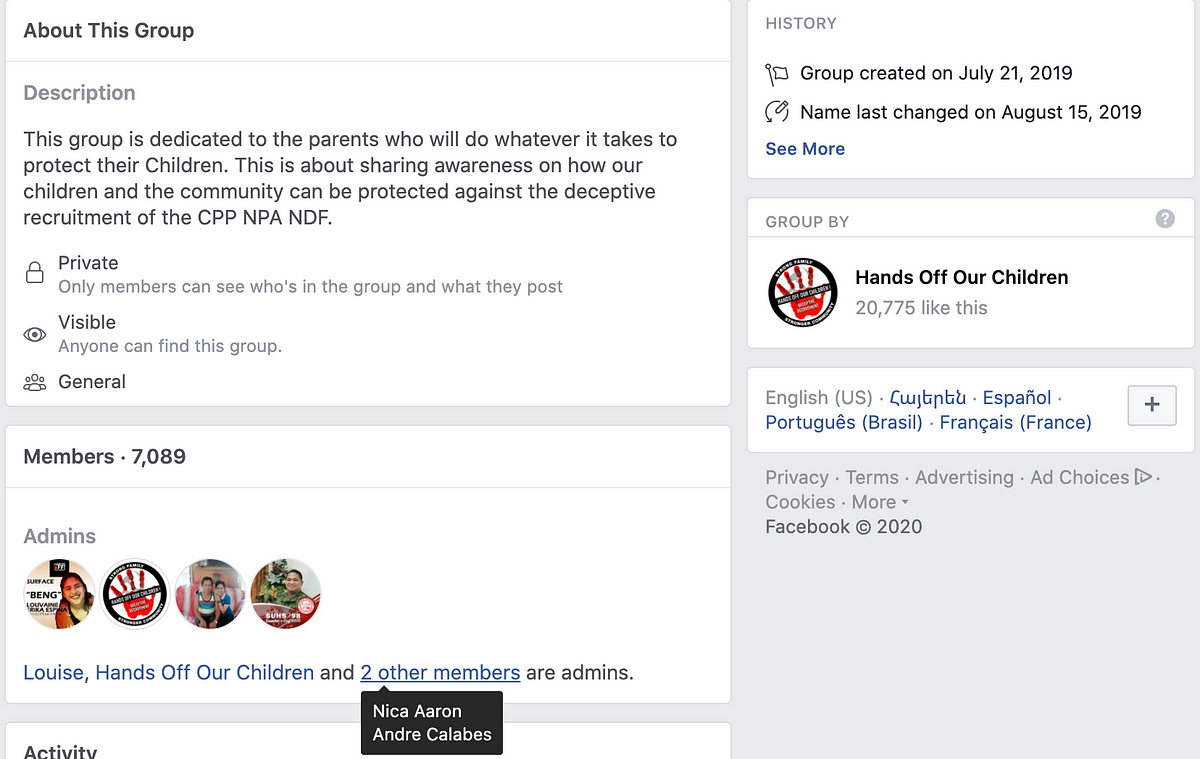

One of the pages in the network belonged to a Filipino advocacy organization called “Hands Off Our Children,” whose About page described it as “a group of mother (sic) fighting against terrorist recruitment.”

“Hands Off Our Children” claimed to represent parents whose children were recruited to the CCP-NPA by the party’s “front organizations” operating in schools. With over 20,000 followers at the time of removal, the page amassed hundreds of engagements and shares per post. Other pages in the network consistently amplified the page’s posts, such as the below video about the school-to-NPA recruitment pipeline, which was viewed over a million times.

There was little information about who was behind the organization online: it had no website, but it was promoted in several news bulletins by the Philippine News Agency (PNA), which is the official newswire service of the government.

Supporting proposed anti-terrorism bill

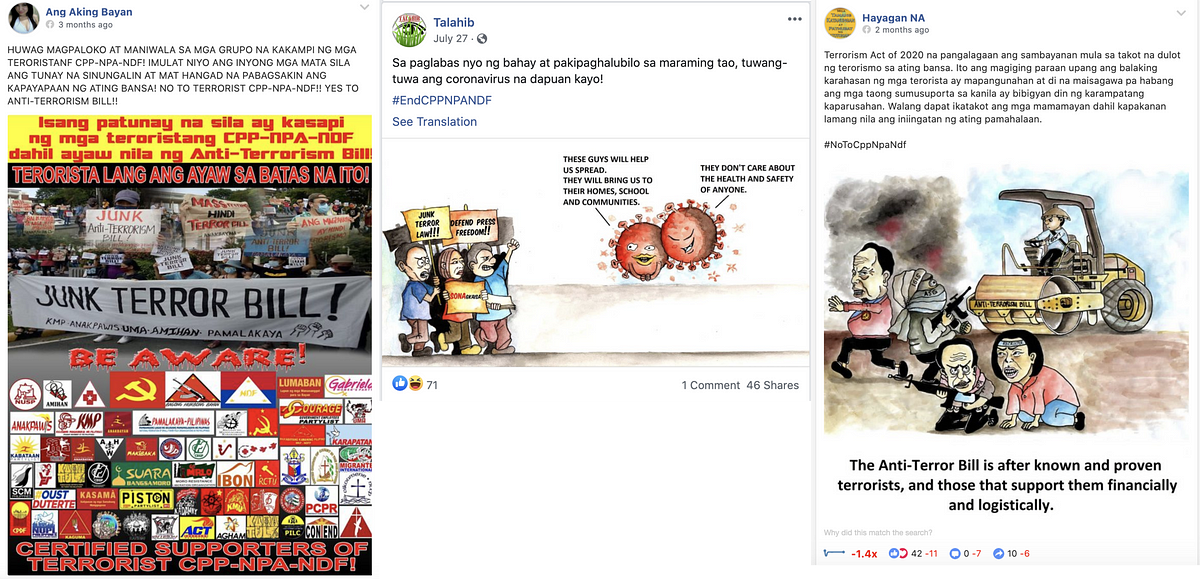

The pages also expressed support for the Terrorism Act of 2020, the contentious bill recently signed into law that has been criticized by rights groups for giving the Philippine government sweeping powers to go after its opponents. The posts accused critics of the bill, many of whom are from progressive organizations or political dissidents, of supporting communist terrorists.

The bill was signed into law by Duterte on July 3, 2020, but still faces hearings before the Philippine Supreme Court scheduled for late September. On August 3, the Philippines’ Armed Forces Chief Lieutenant General Gilbert Gapay said that the military hoped to use the law to regulate social media.

Red-tagging political activists

Many of the pages in the network also engaged in red-tagging — the practice of branding progressive politicians or activists as NPA sympathizers, usually sans evidence.

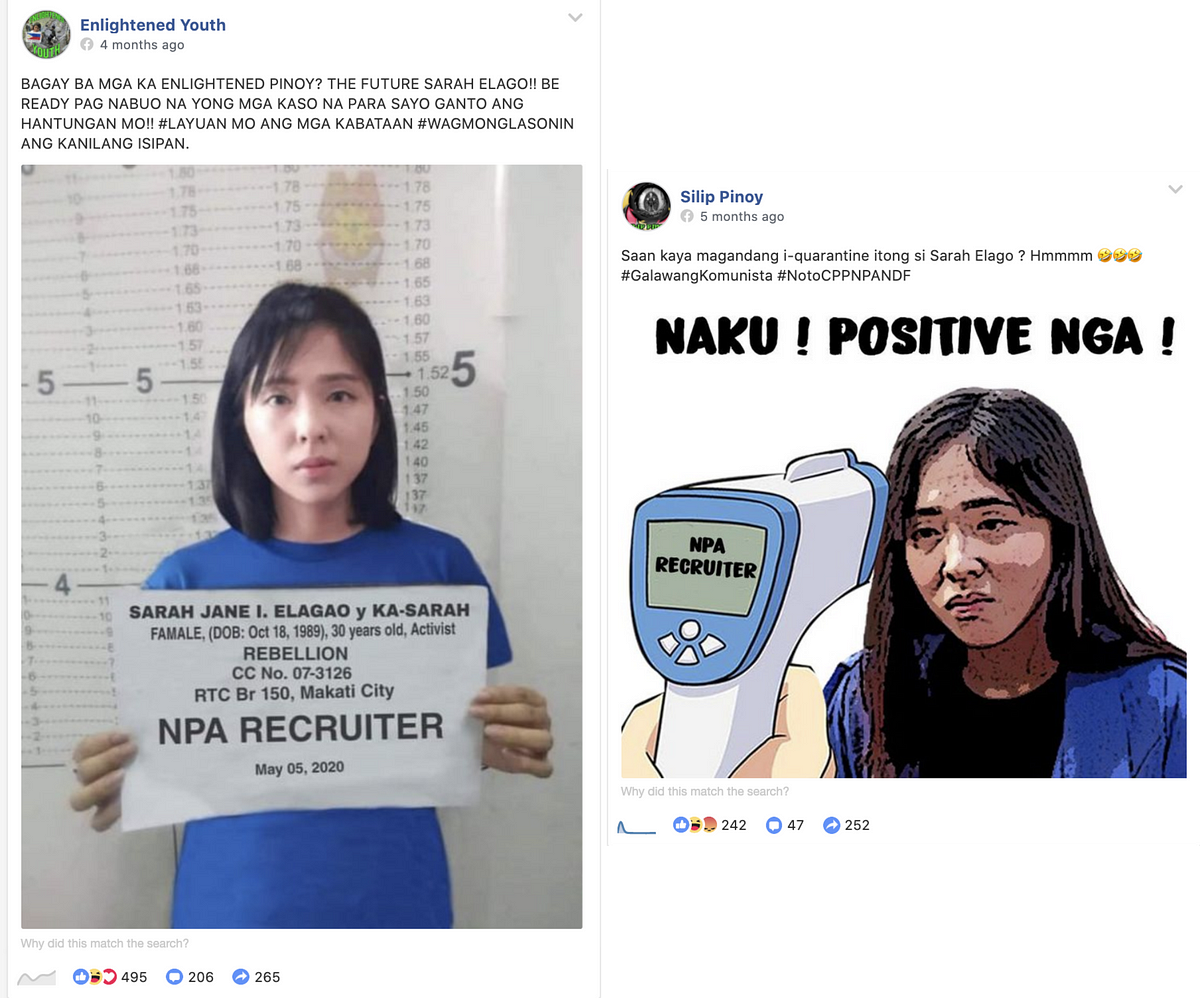

Multiple pages attacked Filipino politician Sarah Elago, a member of the Philippine House of Representatives and the youngest woman lawmaker in the country, accusing her of recruiting students to the NPA. Elago, a member of the progressive Kabataan Party-list, which represents the interests of youth groups, has been a frequent target of red-tagging and other harassment from state-sponsored actors, including the Armed Forces of the Philippines.

A post spread by the pages that showed Elago in a prison lineup holding a sign identifying her as an “NPA Recruiter” was actually doctored and had been identified as such and debunked by AFP Fact Check in June 2020.

On July 16, 2020, Elago tweeted that she had filed a complaint before the NBI Cybercrime Division and Commission on Human Rights “on the dangerous, damaging red-tagging of student & youth leaders & organizations.”

Filed a complaint on the dangerous, damaging red-tagging of student & youth leaders & organizations before NBI and CHR today. Call to probe into the online smear campaign to intimidate the youth, silence dissent! Purveyors of false info, fake allegation must be held accountable✊ https://t.co/17CZhoysl9

— Sarah Elago (@sarahelago) July 16, 2020

Links to the Philippine military

Facebook also shared 42 user accounts and 28 Instagram accounts with the DFRLab. The majority of these were personal accounts, many of which had extensive posting histories and appeared to belong to individuals serving in the Philippine Army.

One of the Facebook accounts included in the takedown, Andre Calabes, belonged to a Philippine Army service member named Alexandre Cabales. According to his LinkedIn profile, Cabales is currently “Chief of the Army Social Media Center, where his primary task is to conduct activities in Social Media that will manage and enhance public perception of the Philippine Army as well as facilitate the delivery of information to the Filipino people about the Army and the government in general.”

While Cabales’ Facebook account bore a slightly different name, the DFRLab was able to determine he was the same man via his photos as well as a personal blog linked to his Facebook account, in which he referred to himself as “Alex Cabales.”

Several open-source traces indicated that Cabales played a key role in the administration of the network. According to a reverse WHOIS search, Cabales was the registered owner of Kalinaw News, a website openly owned by the Civil-Military Operations Regiment of the Philippine Army that many of the pages in the network repeatedly amplified, although the outlet’s own Facebook page was not included in the takedown, perhaps because it openly stated its affiliation with the military. Kalinaw News consistently published content praising the army’s anti-terrorism efforts and attacking the NPA.

Other user accounts in the set were also linked to Kalinaw News. Two of them — Erwin Pagay and Jamaiela Ellaine — were listed as contributors on the outlet’s website. Another, Kenzaike Magz, was the admin of a private group called “Kalinaw Pl.” Moreover, one of the Instagram accounts, Buhay Sundalo, stated in its bio that it had been created “by Kalinaw News.” According to the Kalinaw News website, the goal of Buhay Sundalo is to humanize Filipino soldiers by depicting “the human nature of a soldier who chooses duty over their personal interest as a testament to their devotion.”

Cabales was also linked to the Hands Off Our Children NGO. His Facebook account was an administrator of a private Facebook group linked to the NGO’s page, along with three other accounts in the network. His role in administering this group suggested that while the Hands Off Our Children movement presents itself as an independent organization led by concerned parents, it may be more closely linked to the Civil-Military Operations Regiment than it publicly lets on.

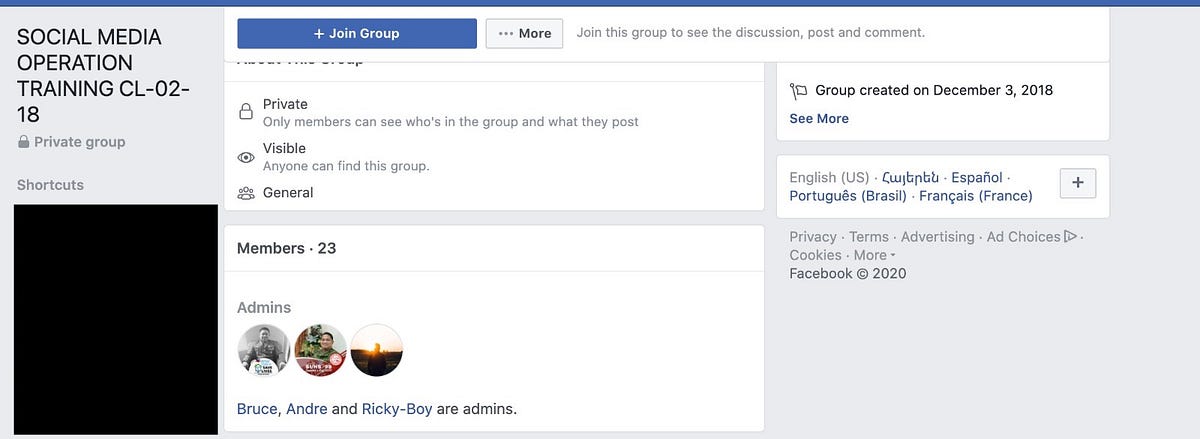

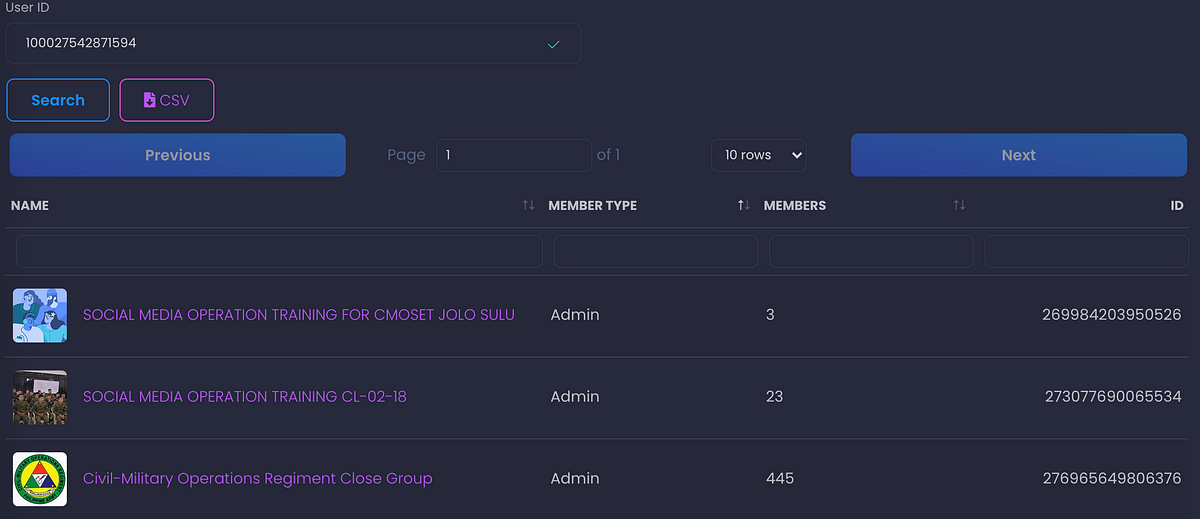

There was also additional evidence to suggest that Cabales and several other military-linked accounts in the network were indeed running some sort of social media operation on behalf of the military and were coordinating with one another in closed Facebook groups. Cabales, for instance, was an administrator of a private group called “SOCIAL MEDIA OPERATION TRAINING CL-02–18,” along with two other profiles included in the takedown: Bruce G. Mayam-o and Ricky-Boy Castro.

Mayam-o’s profile showed him in military uniform, wearing a name plate. “Ricky-Boy Castro,” meanwhile, was also an admin of two other groups: a group called “SOCIAL MEDIA OPERATION TRAINING FOR CMOSET JOLO SULU” and the “Official Civil Military Operations Regiment” closed group, which indicated that he served in the same regiment as Cabales.

Without access to these private groups, however, it could not be determined whether they were being used as a planning ground for coordinating the inauthentic network.

Coordinated behavior

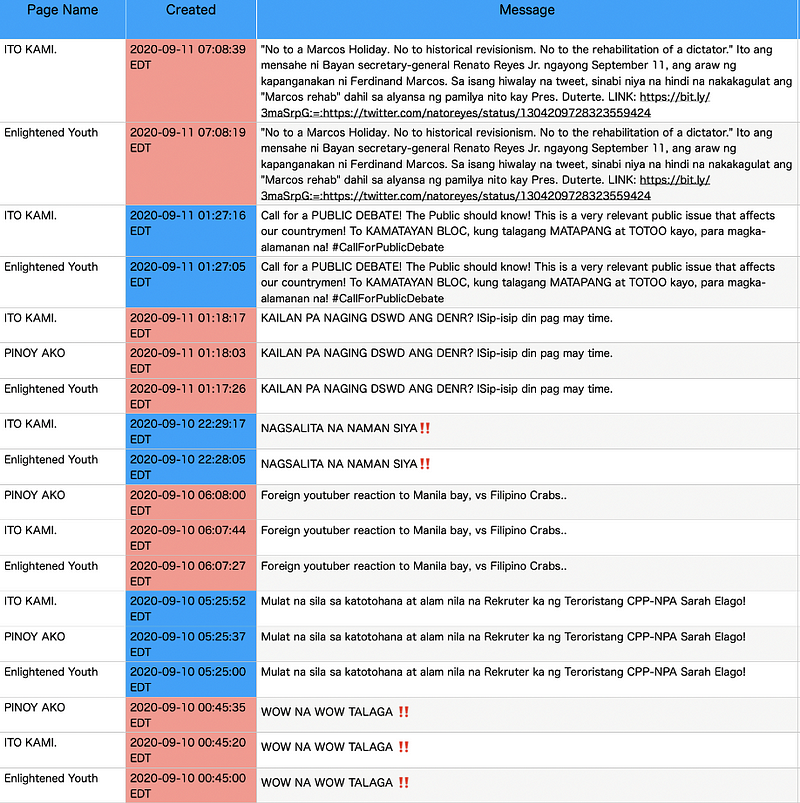

Two clusters of pages within the broader network coordinated with one another, posting identical content within one minute of each other on numerous occasions.

The first and most coordinated cluster consisted of four pages: “Enlightened Youth,” “ITO KAMI,” “Pinoy Ako,” and to a lesser extent, “Masang Pinoy.” These pages posted the same photos accompanied with identical text within under a minute from each other on a systematic basis, a pattern that betrays a strong degree of technical coordination.

The second cluster of pages concentrated on amplifying a page called “Ang Akin Bayan.” Like most of the pages in the network, “Ang Akin Bayan” posted incendiary content attacking the NPA, referring to it repeatedly as a “communist terrorist group,” and engaging in the red-tagging of politicians. Recently, the page targeted Nelsey Rodriguez, a provincial official of the left-wing Bayan political alliance, accusing her of being an “NPA terrorist” in a post about her recent arrest on suspicion of murder. The post was shared within one minute by three of the amplifying pages: “Bantayog,” “League of Democratic,” and “Jona zizon.”

In a Twitter thread posted on September 8, 2020, Karapatan, a human rights NGO in the Philippines, referred to the charges against Rodriguez as “trumped up” and accused the Duterte government of harassing activists and critics “while it protects the interests of criminals, murderers, and plunderers.”

While murderers and criminals like United States soldier Joseph Scott Pemberton are granted absolute pardon, activists, government critics, and the poor in the country face growing threats and intensifying harassment from the State. pic.twitter.com/GSXI8314Se

— Karapatan (@karapatan) September 8, 2020

Outside of these small clusters, there was little open-source evidence of coordination among the assets in this network. Multiple pages amplified one another’s content over time on a repeated basis, as did accounts, but they seldom did so simultaneously.

Zarine Kharazian is Assistant Editor with the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (@DFRLab).

Tessa Knight is a Research Assistant, Southern Africa, with the DFRLab and is based in South Africa.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.