As thousands called for Bolsonaro’s impeachment, limited coverage and pro-Bolsonaro narratives clouded the information environment

By Luiza Bandeira

On May 29, 2021, Brazilians in opposition to President Jair Bolsonaro took to the streets for the first time since the beginning of the pandemic. In the country with the second highest COVID-19 death toll in the world, organizers estimated that 420,000 people left their houses to protest in 200 cities. The protests were primarily peaceful, but two men were injured by the police in the city of Recife, in Northeastern Brazil, and partially lost their sight.

Despite the size of the protests, many traditional media outlets did not cover the protests as the leading news story, despite doing so for previous anti-government and pro-government demonstrations.

Additionally, Bolsonaro supporters used social media to spread fake debunking posts claiming that the protests were in fact empty, and that the opposition was using old images to claim that they were crowded.

The relative silence of traditional media and the spread of disinformation by Bolsonaro supporters might be an indication of how the information environment will look over the next year, as Brazil prepares for general elections. Bolsonaro is expected to run for reelection, possibly facing former president and rival Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who was recently released from jail and is now allowed to run again.

Protests and COVID-19

Since the beginning of the pandemic, President Jair Bolsonaro has denied its severity and discouraged social distancing measures. He has promoted political gatherings in which participants do not maintain social distance or wear masks most of the time. The last event of this kind happened on May 23, when Bolsonaro participated in a motorcycle demonstration in Rio de Janeiro with many unmasked supporters waiting for him along the way.

Those that oppose Bolsonaro, however, had not been to the streets in large-scale demonstrations during the pandemic. Instead, they had engaged in pot-banging protests, a traditional form of protest in Latin America, to express their disagreement with the government’s handling of the public health crisis.

The May 29 anti-Bolsonaro protests were called as the country approached 450,000 COVID-19 deaths. Largely wearing masks, demonstrators protested against Bolsonaro’s handling of the pandemic, many supporting his impeachment. The demonstrators also demanded access to more vaccines and an increase in cash transfers to people affected by the pandemic, among other things. The demonstration was organized by opposition parties, workers unions, and student organizations, though some organizations did not join the protests due to pandemic concerns.

The anti-government protests happened during a fragile political moment for Bolsonaro. The president saw his approval ratings reach their lowest point in May 10, with only 24 percent of Brazilians approving of his government. Brazil’s Congress is currently investigating his administration’s handling of the pandemic. Meanwhile, corruption convictions against former President Lula were annulled in March 2021, opening the path for him to run against Bolsonaro in 2022. Lula was the front-runner in the previous presidential race until he was prohibited from running due to the charges in 2018. Only after his exit from the race did Bolsonaro take the lead.

Lack of media coverage

Brazilian traditional media did not cover the protests as it had previous demonstrations, whether they had been organized for or against the government.

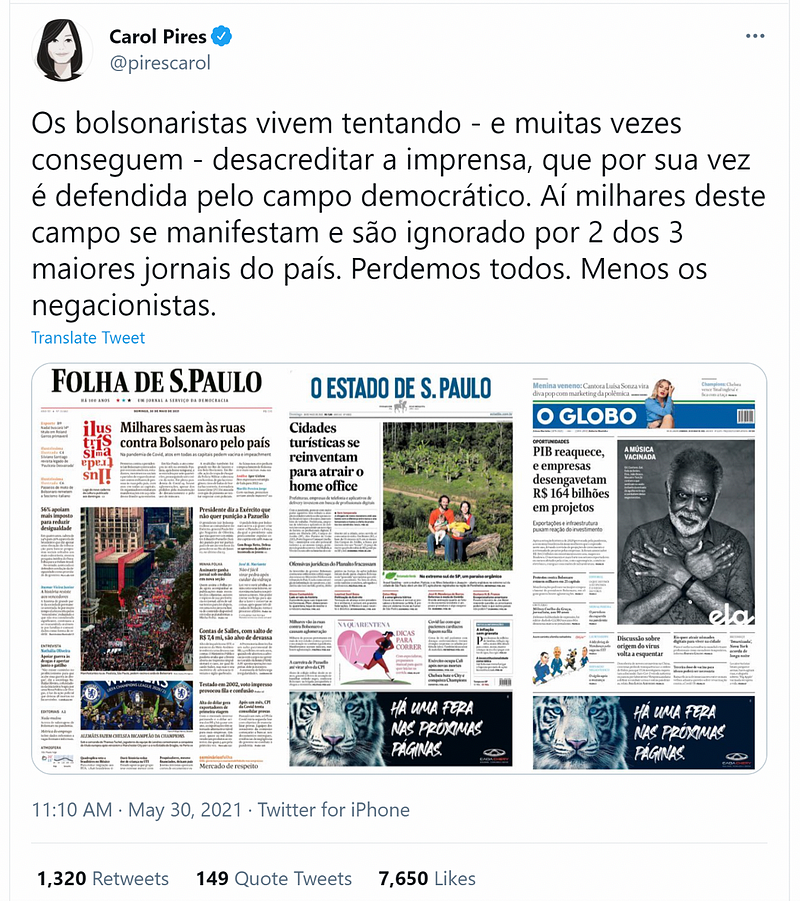

Among the three main national newspapers, only one (Folha de S.Paulo) featured the protests in the headline of their print Sunday edition. O Estado de S. Paulo decided to highlight how “touristic cities were reinventing themselves to attract home office [workers],” leaving the coverage of the protests to a small note “below the fold” — the bottom half of the front page, a place considered less prestigious on newspaper covers. O Globo also published only a small note about the protest on its front page, devoting the main headline to positive news about the economy.

This approach was different from coverage of previous protests. On May 24, for instance, O Globo published a large image of the pro-Bolsonaro motorcycle ride on its cover. Even though the coverage was critical, the pro-Bolsonaro protest ended up getting more page space than the recent anti-Bolsonaro protest.

Brazil’s traditional media outlets were criticized in 2018 for not recognizing Bolsonaro as a far-right candidate and drawing false equivalencies between Bolsonaro and his main opponent, Fernando Haddad. Following the latest protests, journalists took to social media to criticize the Brazilian press for their lack of coverage.

“Bolsonaro supporters always try — and often succeed — to discredit the press, which is supported by the democratic field. Then thousands from this field protest and are ignored by two of the biggest three newspapers in the country. We all lose, except the denialists,” wrote journalist Carol Pires.

TV stations in the country also did not highlight the protest. There were no live transmissions of the event by 24-hour news cable channels such as GloboNews and CNN Brasil, as had been the case during previous protests. The main news broadcast in the country, TV Globo’s Jornal Nacional, dedicated three minutes and 24 seconds to the protests in its Saturday edition, or approximately seven percent of the edition. Another news broadcast, Jornal da Record, did not mention Bolsonaro’s name in the piece, saying only that “anti-government” protests had occurred.

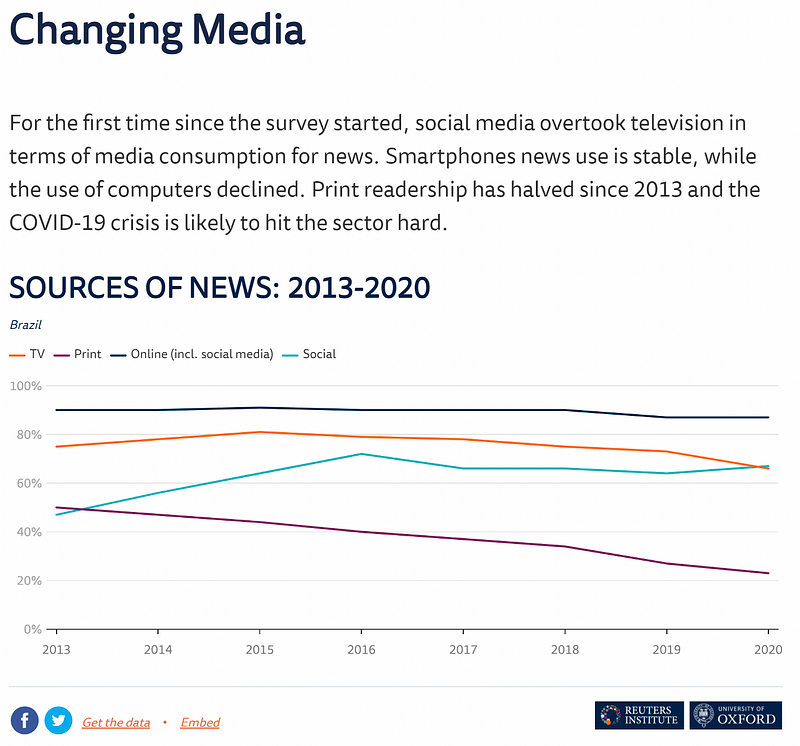

According to the latest Reuters Digital News report, online publishing (including social) overperformed TV as the main source of news for Brazilians for the first time in 2020. Commercial TV, however, still plays a large role in Brazilians’ media diets, however.

Fake debunkings

While traditional media largely avoided major coverage of the protests, on social media Bolsonaro supporters went one step further to spread disinformation about the unfolding demonstrations. Many of them claimed images of old protests were being published by Bolsonaro opponents as if they were from Saturday to falsely claim that protests were larger than they actually were.

One tweet claimed that Guilherme Boulos, a leftist presidential candidate in 2018, used a picture from 2016 and presented as if it had been taken on May 29, 2021. The images shown in the tweets, however, are different events. In the one posted by Boulos, a giant inflatable balloon representing Bolsonaro is visible in the crowd. In the image from 2016, the balloon is absent, suggesting it is a different image entirely. Other disinformation actors went further, replacing the image in the screenshot of the 2016 article to falsely present the photos as identical, as reported by O Estado de S. Paulo newspaper.

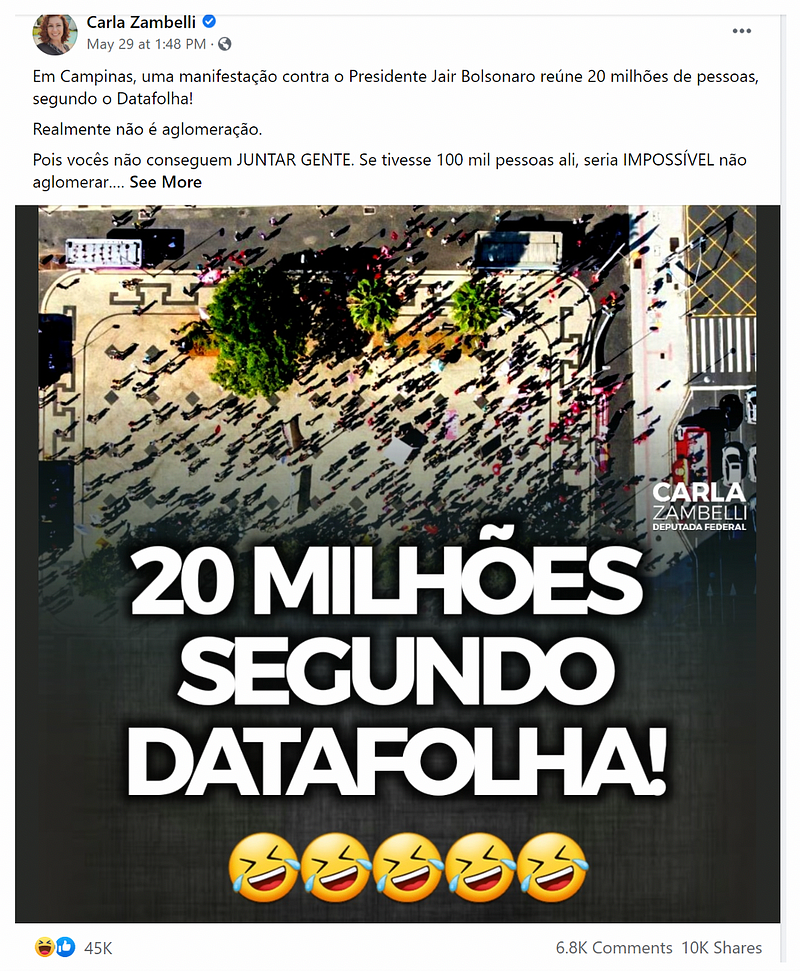

Congresswoman Carla Zambelli, a vocal Bolsonaro supporter who has been criticized for spreading disinformation, also claimed that the opinion pollster Datafolha (from the same group that owns Folha de S. Paulo newspaper) published that there were 20 million people protesting in the city of Campinas. The congresswoman tried, then, to debunk the claim, saying that the opposition did not have enough support to produce a massive gathering of that size.

It is unclear from the post whether Zambelli was being ironic or intentionally misleading, as Datafolha never published this statistic and did not attempt to estimate the number of people attending the protests. Even if Zambelli’s goal was to be ironic, comments in the post showed that many people actually believed that Datafolha was trying to artificially inflate the number of protesters.

On a smaller scale, there were posts that indeed used old images as if they were from the May 29 protests. For example, posts circulated on Twitter and WhatsApp using an image of supporters of the Flamengo soccer team celebrating the victory in Libertadores championship in 2019, claiming they were of the crowd at the protests.

Twitter conversations

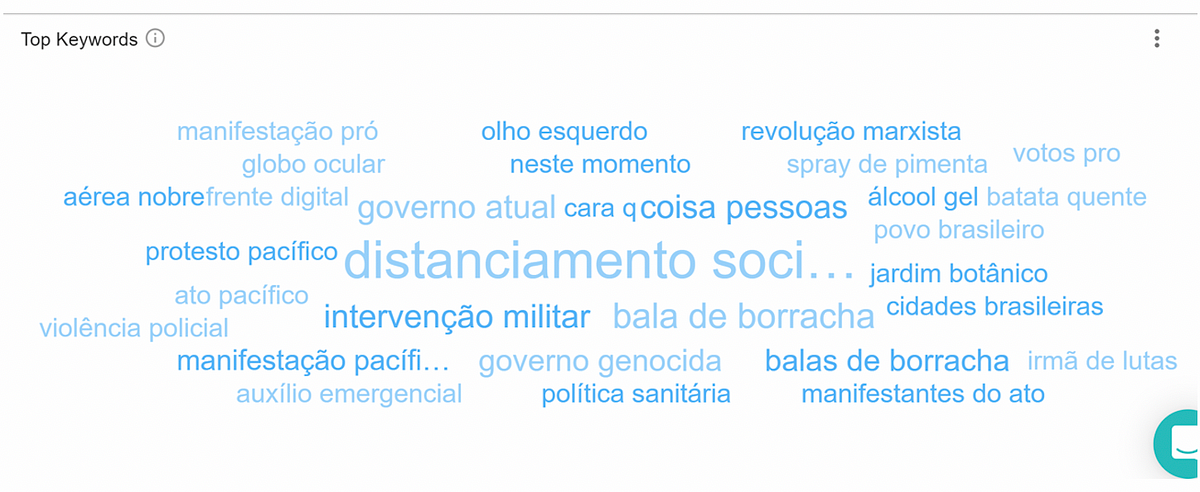

Using the media analysis tool Meltwater, the DFRLab found that more than 1.5 million tweets were posted about the protests on May 29. An analysis of the words that appeared the most in tweets shows that the Portuguese equivalent of “social distancing” was one of the most popular phrases mentioned in tweets, reflecting the debate about protesting in the middle of a pandemic. Portuguese phrases related to the protesters’ agenda, such as “sanitary policy,” “emergency aid,” and “genocidal government” also appeared. Finally, there were mentions of “left eye,” “police violence,” and “rubber bullets,” in reference to the violent police crackdown in the city of Recife.

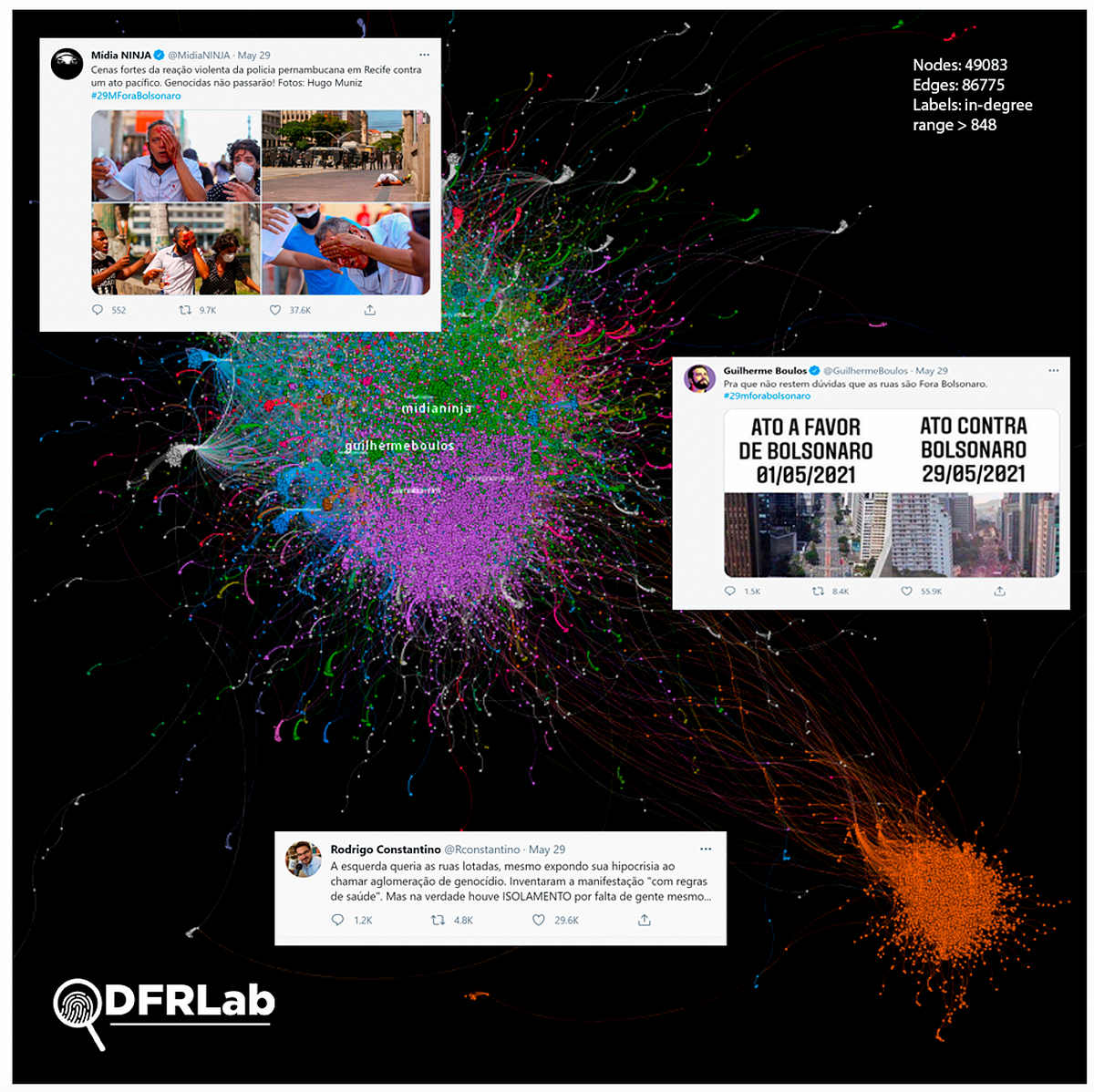

The DFRLab analyzed a sample of 100,000 tweets and discovered that anti-Bolsonaro tweets (the large, colorful cluster in the graph below) overperformed pro-Bolsonaro tweets (in orange). Among the most retweeted posts in the anti-Bolsonaro cluster were Boulous’s tweet comparing pro-Bolsonaro protests on May 1 with the May 29 demonstrations, and a tweet from the media collective Midia Ninja talking about the violence in Recife. The most popular tweet of the pro-Bolsonaro cluster came from right-wing journalist Rodrigo Constantino, who claimed that the left wanted to promote a large gathering while criticizing Bolsonaro for doing the same. In the same tweet, Constantino also claimed that the protests were attended by few people.

Brazil emerged from the 2018 election with a hyper-polarized, increasingly partisan media environment. As Brazilians prepare for next year’s election, it will be pivotal to study and understand how both the country’s traditional and new media outlets report on critical events, such as mass demonstrations.

For the first time since the beginning of the pandemic, critics of the Bolsonaro government took to the streets to protest the government’s mismanagement of the pandemic. In response, pro-Bolsonaro actors spread false and misleading information about the protests, while the traditional press, which would typically be one of the safeguards against disinformation, also failed to accurately inform its audience.

Luiza Bandeira is an Associate Editor with the DFRLab.

Esteban Ponce de León, Assistant Researcher with the DFRLab, contributed to this article.

Cite this case study:

Luiza Bandeira, “Muted media coverage and fake debunkings as Brazilians protest Bolsonaro’s COVID response,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), June 3, 2021, https://medium.com/dfrlab/muted-media-coverage-and-fake-debunkings-as-brazilians-protest-bolsonaros-covid-response-d50a29e9f028.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.