Armenia-based Facebook pages published emotional content to attract commenters, then edited the posts to link to their websites

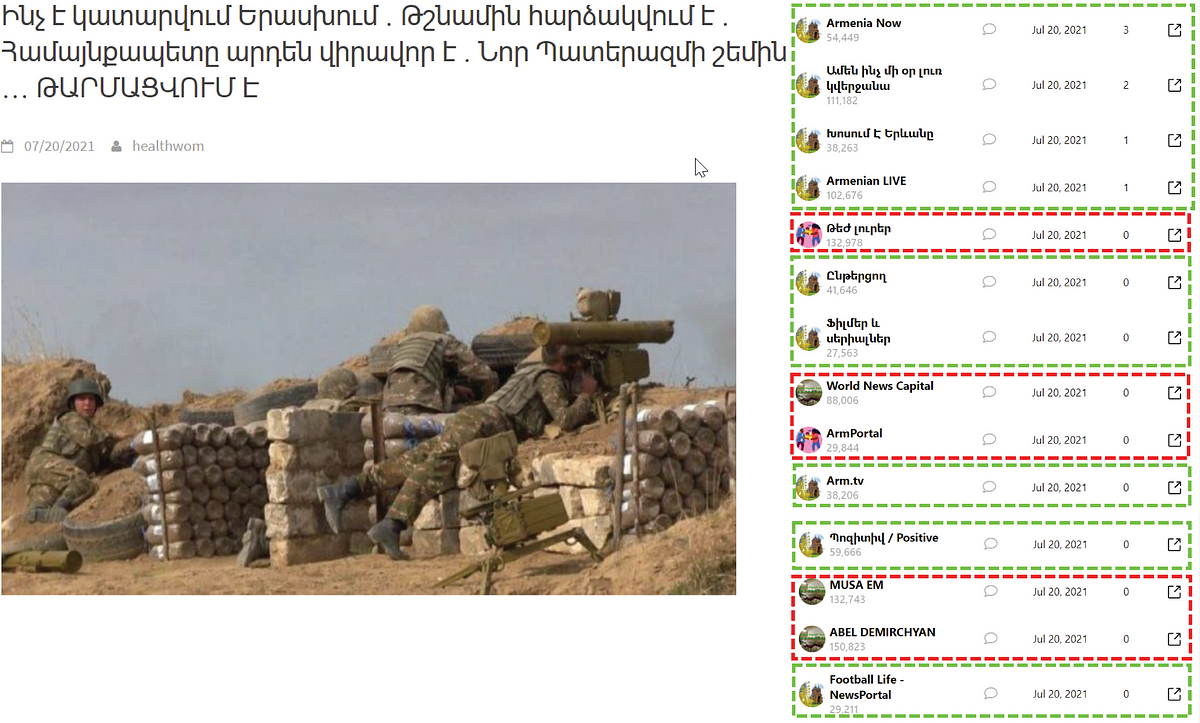

Multiple Facebook pages amplified fringe news from related external websites that targeted both Armenian and Ukrainian audiences in their respective languages. The Facebook pages pretended to be legitimate media outlets but published sensational content stolen from other sources as a means of audience-building. Many of the identified Facebook pages had hundreds of thousands of followers.

While this network fits the larger trend of inauthentic pages targeting Ukraine, it is the first instance observed by the DFRLab to be administered from — and targeted at — Armenia. In November 2020, Armenia lost a military conflict against neighboring Azerbaijan, which concluded after the former signed a ceasefire agreement widely considered to be disadvantageous to its own side. Currently, Armenia is in the middle of a political crisis, and inauthentic social media campaigns such as the one identified as a part of this research could fuel the ongoing tensions in the country.

The DFRLab identified an expanded network of websites, connected via Google Analytics or Google AdSense, whose stories were amplified by a set of seemingly affiliated Facebook pages. These pages coordinated to amplify the external websites’ content; in some cases, they appear to have exploited a workaround on the platform to artificially amplify engagement on a posted link. This latter case arose in instances where a Facebook page re-shared a post originally published to a public Facebook group. These posts usually discussed something emotionally resonant, like offering birthday wishes, that would drive other users to comment, thereby increasing engagement. These posts would then be edited to include a link to one of the external websites. Users seeing the re-shared post for the first time would not know that the original text had been altered.

Websites and subdomains

The DFRLab identified a network of 59 websites and subdomains that all promoted exaggerated or fabricated content in Armenian, Russian, and Ukrainian. Of these, at least 16 of them partially published content in Ukrainian and Russian that covered Ukrainian affairs, while 48 covered Armenian news in Russian, Armenian, and English. Some of the websites published Armenian content prior to also posting stories in Ukrainian, and others published pieces in multiple languages. The content of these websites was usually comprised of stolen blog posts or outdated news stories. The structure and user interface of the websites was not user-friendly, which suggested that direct visitors were not intended as their primary audience, in contrast to referral traffic from social media.

The blog posts themselves were often sensationalistic in nature, seemingly intended to provoke strong emotional responses rather than offering up dry news coverage. For instance, the website ukrtime.site recently featured on its main page stories about Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s comments on a large Orthodox pilgrimage event where participants were not wearing face masks; a photo of person who resembles Vladimir Putin at the same event; ongoing extreme weather conditions in Ukraine; and Russian rocket strikes in eastern Ukraine. The headlines for each of these stories was written provocatively, likely as a means of generating clicks.

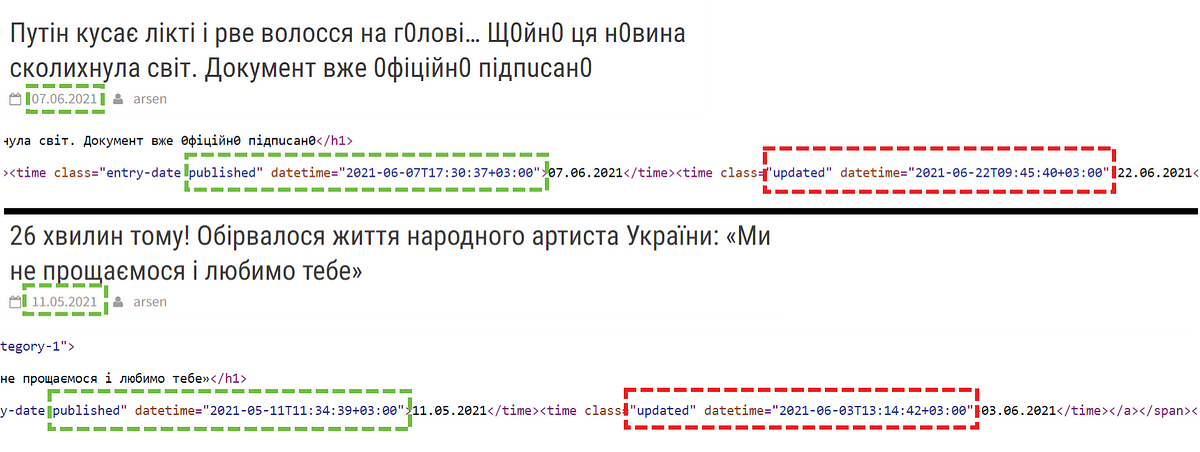

The websites also appeared to edit their content often. An examination of the websites’ source code showed that multiple articles were modified a few weeks after they were originally published, which may have impacted their later appearance on Facebook. These edits, only known through reviewing the source code, could have ranged from a single character edit to modification of the whole article.

The DFRLab identified this network of similar websites by identifying overlaps in their Google Adsense or Analytics codes, as well as their design, content, and mode of dissemination. For instance, a majority of the websites were built using WordPress and used the same template, and the operators often failed to change default placeholders, such as having an address of “Address, 123 Main Street, New York, NY 10001.” The DFRLab identified at least three distinct website styles in this network.

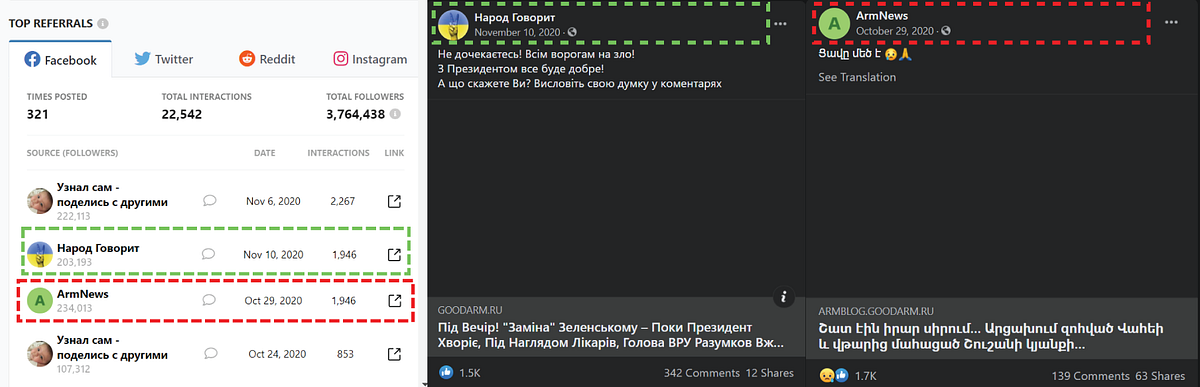

Some of the websites mixed languages, delegating their secondary language sections to subdomains. For instance, a CrowdTangle query showed that the now-defunct goodarm.ru was popular among both Ukrainian and Armenian-speaking audiences on Facebook, though the main page showed only Ukrainian-language content. Armenian-language content, meanwhile, was buried in the subdomain armblog.goodarm.ru.

Some of the content that made its way onto the affiliated Facebook assets was originally published on the subdomains of seemingly unrelated websites. For instance, the website trat-plitka.ru sells pavement slabs around greater Moscow, but a now-defunct subdomain of the same website — ukr.trat-plitka.ru —published fringe news in Ukrainian.

Popular Facebook news pages in Ukrainian

The DFRLab identified 85 affiliated Facebook pages that shared the news from the identified websites. The overall operation on Facebook was familiar, as pages seemed to coordinate in amplifying the content from the websites and adding a short comment alongside the links. All of the investigated pages had administrators located in Armenia, according to their respective transparency sections.

The DFRLab found that some of Facebook pages posting links to stories in Ukrainian had received thousands of engagements. The content was often stolen from mainstream and fringe external websites, including stories about car accidents or military losses, as well as political content to sow mistrust of the authorities or politicians.

Some of the pages also appeared to be attempting to skirt Facebook’s policies by sharing posts to public groups that included links to the same external websites, injecting more content from the same external websites across the network.

For example, at 10:01 p.m. local time on May 31, 2021, a user account posted a link to a story on the website novii.xyz to the public Facebook group “ABS.” Within one minute, that group post was shared on two other Facebook pages in the network, “News 24” and “Latest News” (both names translated from Russian).

The pages also appeared to engage in inauthentic behavior. Posts on News 24 and Latest News garnered multiple out-of-context comments. For instance, there were news articles about the death of a Ukrainian actor, but commenters had posted birthday wishes and praised a child for being cute, both of which were complete non-sequiturs to the topic at hand. Other commenters posted celebratory GIFs. This created a perception that the comments may have been intended for a different story or, more insidiously, to give the post more positive engagement in an attempt to trick Facebook’s algorithms to into placing the story in more users’ feeds.

Such cases were typical on several of the identified pages. Some user accounts commented on the discrepancy between the content of the story and the comments, but they were far in the minority. A comparison of comment dates likely explains part of this trend. The people who found a discrepancy were the most recent to comment, hinting that perhaps the content of the original post might have changed — i.e., the early comments on the post reflected the topic of the post prior to editing, while later comments only saw the edited post with a completely different topic, alongside the original comments. Additionally, there was nothing included in the updated text to acknowledge they had been rewritten.

This trend may be partially explained by edits to the articles on the external websites. For example, a story about an airplane crashing upon landing also received a litany of happy birthday wishes in the comments. At the same time, the article only appeared on Facebook on July 14, well after it was last edited on July 3, according to the source code.

Another possible explanation of such a discrepancy is the change of the post on Facebook itself. A link to the plane crash story was published in a public group, then immediately within the same minute minute to a page. Edits to the text of the original post to the group, however, revealed that the post was originally a picture with a description that a disabled person had a birthday and that nobody wanted to wish him well. One hour later, however, the author edited the post, replaced the original content with new text and a link to the plane crash story on the external website.

Users who first saw the post on the page, however, would have been unable to see the changes to the content that could be determined by looking at the “edit history” of the original post in the group.

A commercial and coordinated network

The Facebook pages in this set also followed a similar pattern, amplifying only one external website at a time. Put differently, these pages posted links to stories from just one of the external websites, to the exclusion of the others, for a period of time before pivoting to posting links exclusively to a different website. Sometimes the page name was identical to that of an external website, but when the same page pivoted to a different source, the name would remain the same.

The pages also appeared to coordinate in posting the same content, often reposting the same story in tranches.

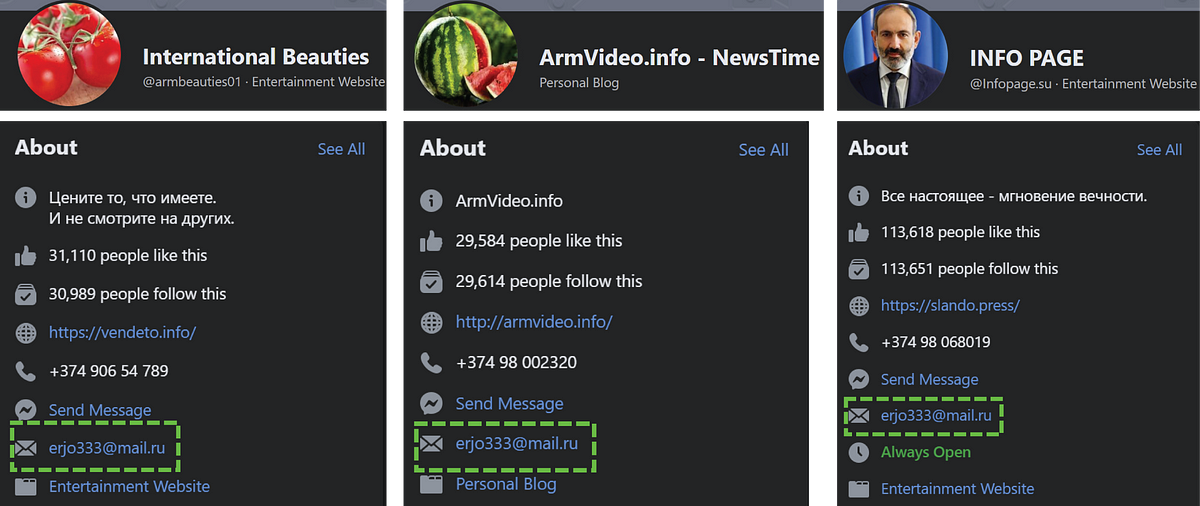

Providing further evidence of coordination, some of the identified Facebook pages used the same contact email, erjo333@mail.ru.

The network seems to be designed for commercial purposes, as its operators offer promotions of other products and pages for a fee. For instance, many of the pages featured the same banner photo offering advertising services. Additionally, at least one page featuring more than 66,000 followers was for sale.

The DFRLab could not establish a connection between the Armenia-based administrators of pages targeting a Ukrainian audience and those targeting an Armenian audience, as this information was not publicly available. However, the pattern of amplifying content from the same websites, those same websites’ templates, and the similar approaches to content dissemination and timing suggest that a coordinated network — either in aggregate or several similar smaller networks — conducted a bait-and-switch of highly engaging content to expose more Facebook users to external content and profit from it.

Roman Osadchuk is a Research Assistant, Eurasia, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Cite this case study:

Roman Osadchuk, “Fringe outlets use bait-and-switch tactics to target Ukrainian and Armenian Facebook users,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), September 17, 2021, https://medium.com/dfrlab/fringe-outlets-use-bait-and-switch-tactics-to-target-ukrainian-and-armenian-facebook-users-8d00a2032bed.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.