Popular Ukrainian Telegram channels employ TikTok clickbait scheme to grow audiences

Promotion scheme uses clickbait TikTok ads and proxy external websites posting sensationalistic and sometimes misleading news content

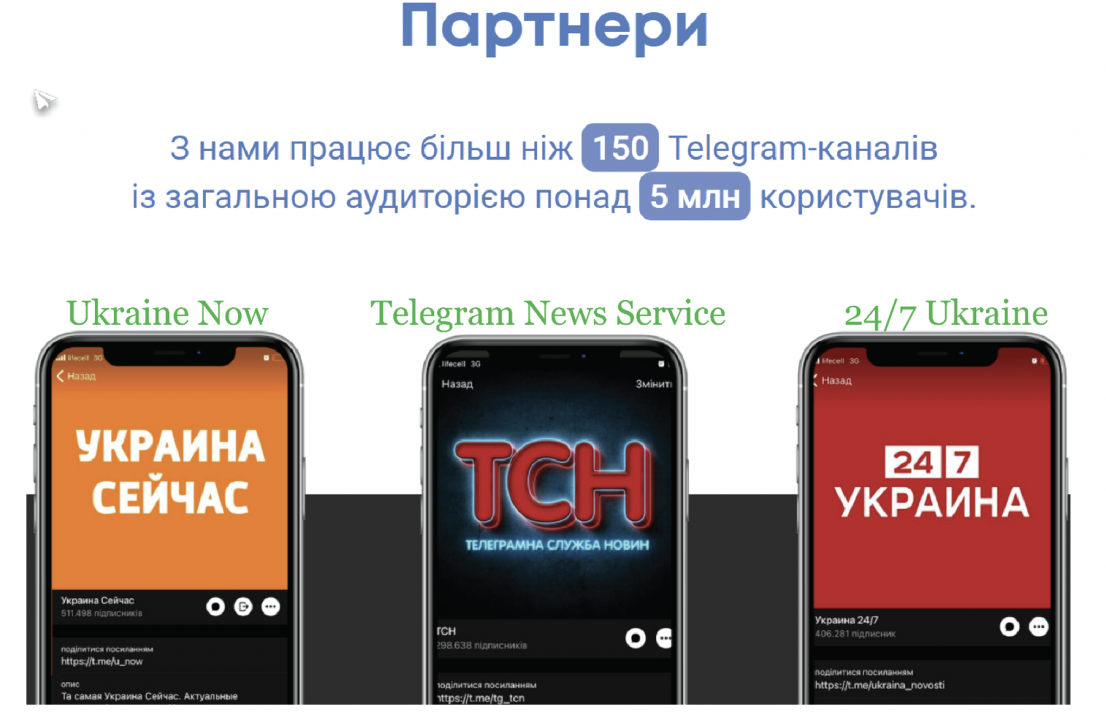

BANNER: Screengrab from a digital agency that boasts working with Telegram channels. The caption says, “Partners. We’re working with more than 150 Telegram channels with the total audience of more than 5 million users.” (Source: Telegram Agency/archive)

TikTok’s paid advertising feature is being employed to route users through low-quality external webpages to Ukrainian Telegram channels known for publishing salacious and emotionally engaging clickbait, stolen news content, posts supporting Kyiv’s embattled mayor, and paid product advertisements.

These Telegram channels appear to be in an audience-building phase and have taken the novel approach of leveraging TikTok. Telegram is the third most popular social media platform in Ukraine and a critical news source that has quickly increased its audience there, with social media surpassing television as the most popular news source in 2019. Alongside the general public, Ukrainian members of parliament are avid users of the platform, often drawn to channels that publish “insider” information and compromising materials about their opponents. Overt audience-building is not a new phenomenon for Telegram channels, but utilizing TikTok’s advertising capabilities for these purposes has added a new twist to Ukraine’s information ecosystem.

In 2020, TikTok had 3.2 million users in Ukraine, and it continues to grow there. And while it is hard to evaluate the success rate of TikTok-based ads growing a Telegram channel’s audience, the simultaneous usage of this promotional tactic by multiple channels suggests that it may be fruitful.

TikTok ads pushing to feeder webpages

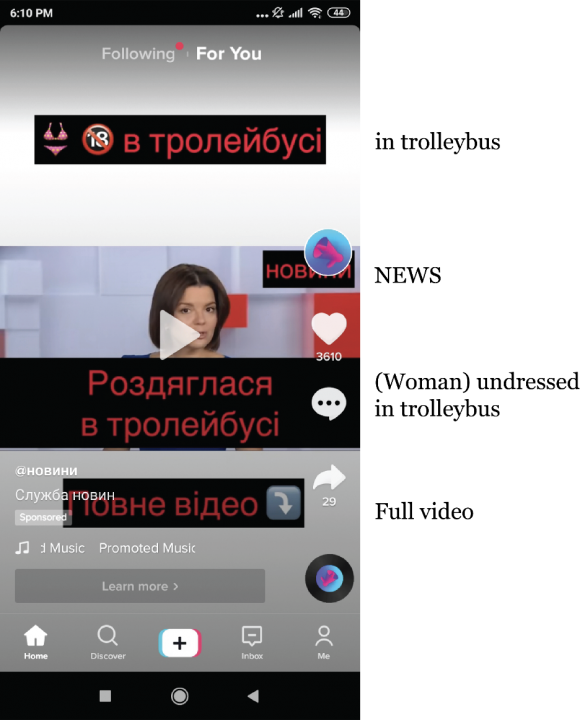

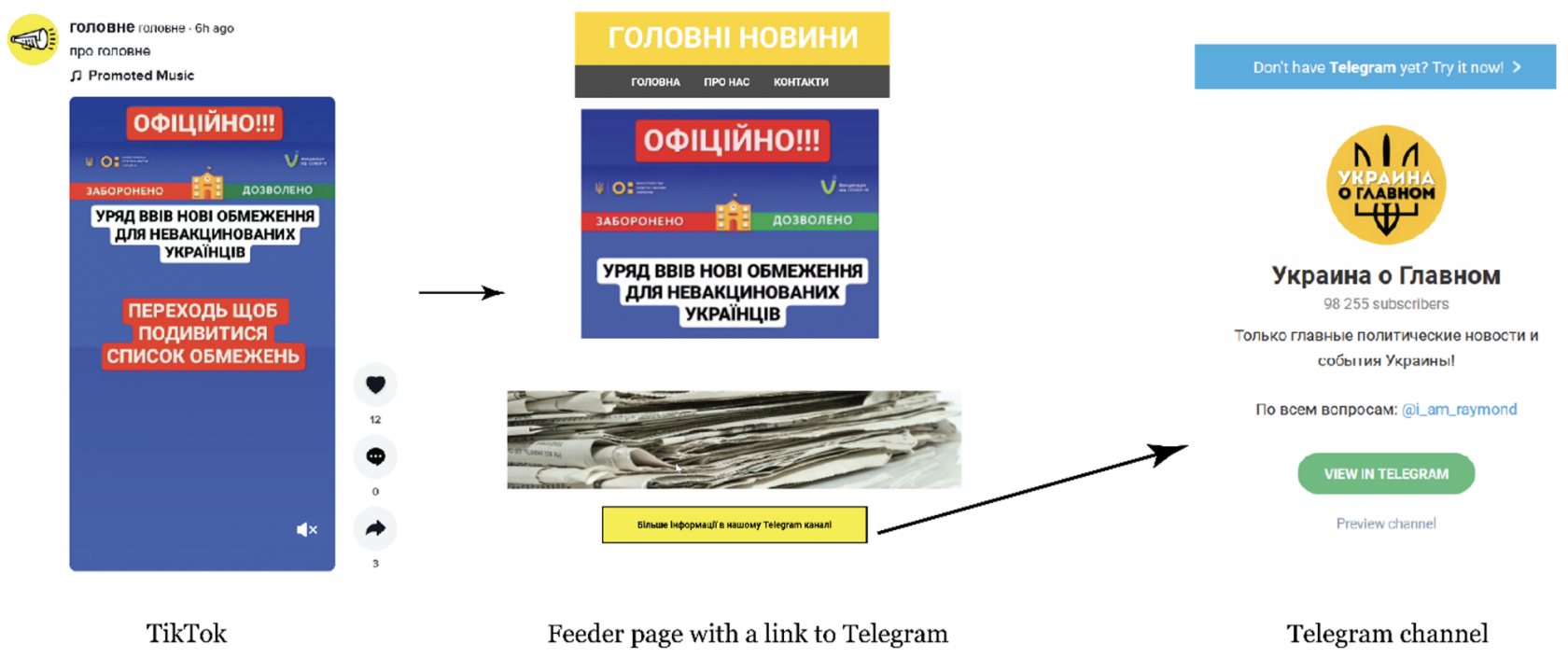

This promotional methodology replicated across many TikTok accounts, external websites, and Telegram channels had three components: TikTok accounts posting highly engaging and misleading videos as advertisements; poorly designed external “feeder” pages serving as conduits for potential channel subscribers; and the Telegram channels themselves. The first step of this operation involves posting a TikTok video with a clickthrough ad. The clickthrough ad functionality appears to be only accessible in the platform’s apps and not its web interface.

TikTok allows users to purchase advertisements for external websites but maintains transparency rules regarding the external webpages to which users are directed after clicking an advertising link. According to TikTok’s advertising policies, external landing pages that are linked to from an ad should not contain “incomplete content or information.” The guidelines also include a specific requirement that external webpages linked to from e-commerce ads must feature basic information about the company information, such as its name, address, and business registration. TikTok also prohibits the “promotion, sale, or solicitation of or facilitation of access to products or services that might be or are considered deceptive, misleading, or unlawful such as: […] Unwarranted claims, misinformation, including pricing/discount or promotion information inconsistency, missing T&C or privacy policy pages, or any of such.”

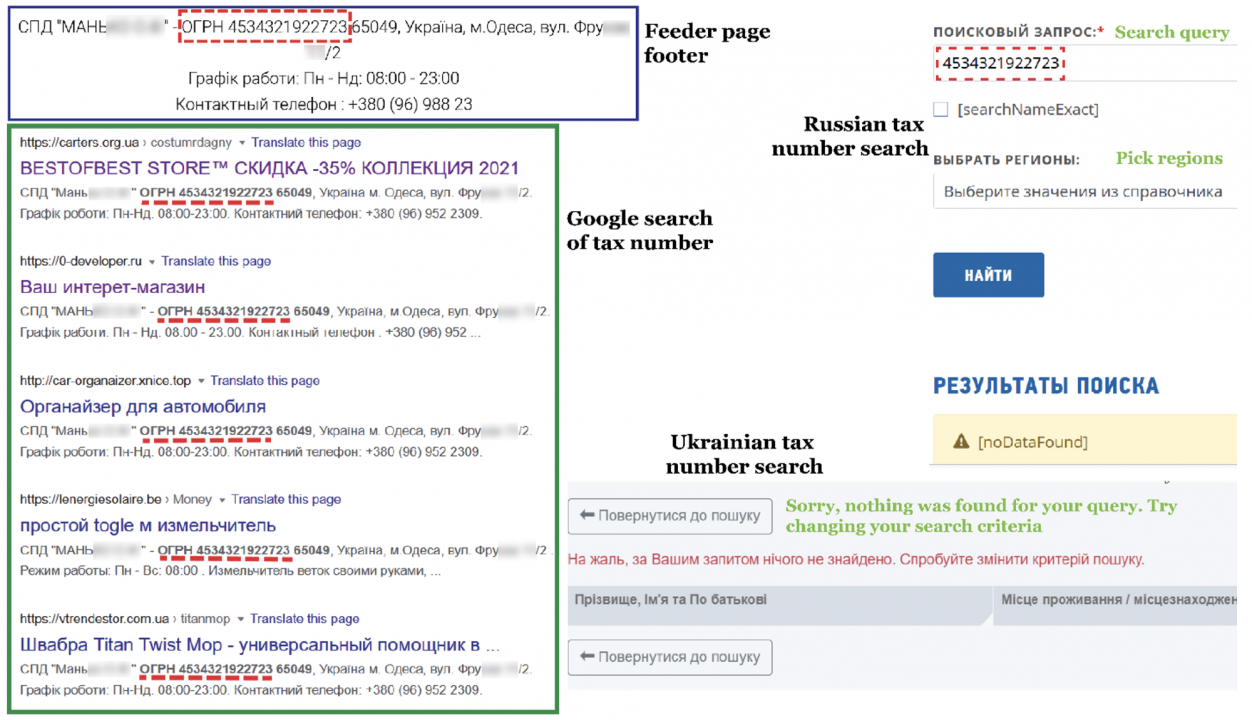

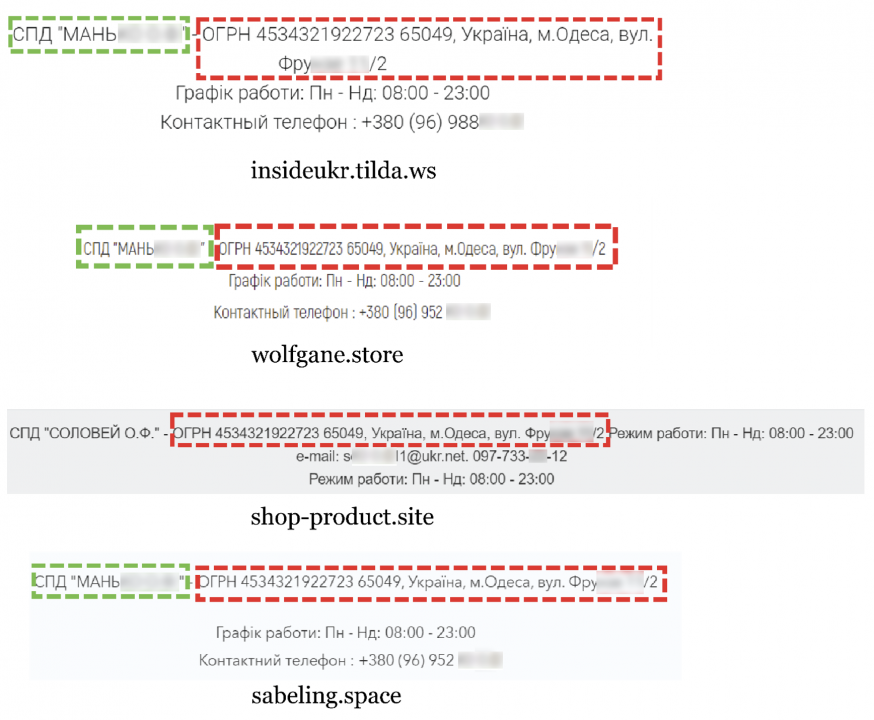

While the pages identified in this case study posed as media entities, it is hard to determine whether they necessarily violated TikTok’s terms of service. That said, the sparsely designed feeder webpages linked from the TikTok ads featured false, incomplete, or stolen contact details. For instance, a feeder page that pushed viewers toward the Insider UA Telegram channel featured information, notably a tax number and address, copied from small e-commerce websites.

The contact details are that of a private entrepreneur in Odessa, Ukraine, but include a Russian tax number, as evident from the abbreviation ОГРН — an acronym meaning “main state registration number” used only by the Russian tax authorities — and the 13-digit number. In contrast, Ukrainian tax authorities use only 10 digits in their tax IDs. Searches for the number in both the Russian and Ukrainian tax registries, however, returned no results. Separately, the Insider UA feeder page appeared to cut a few digits from a Ukrainian cell number that was otherwise available under the contact details for the e-commerce websites. The DFRLab also investigated the named entrepreneur and found no conclusive evidence that would connect any of the resulting matches to any of the feeder pages examined; for this reason, the person’s name has been redacted.

The websites’ text was usually accompanied by stolen pictures from press events or stock photos of newspapers. Some pages have contact details like an email address, phone number, or tax number, but none of the mentioned tax ID numbers except one appeared to be valid or found in the Ukrainian tax registry. Only one of the identified feeder pages, perepichka.news, featured an actual tax number corresponding with an actual business name, though its design template was somewhat different than all the rest of the feeder pages.

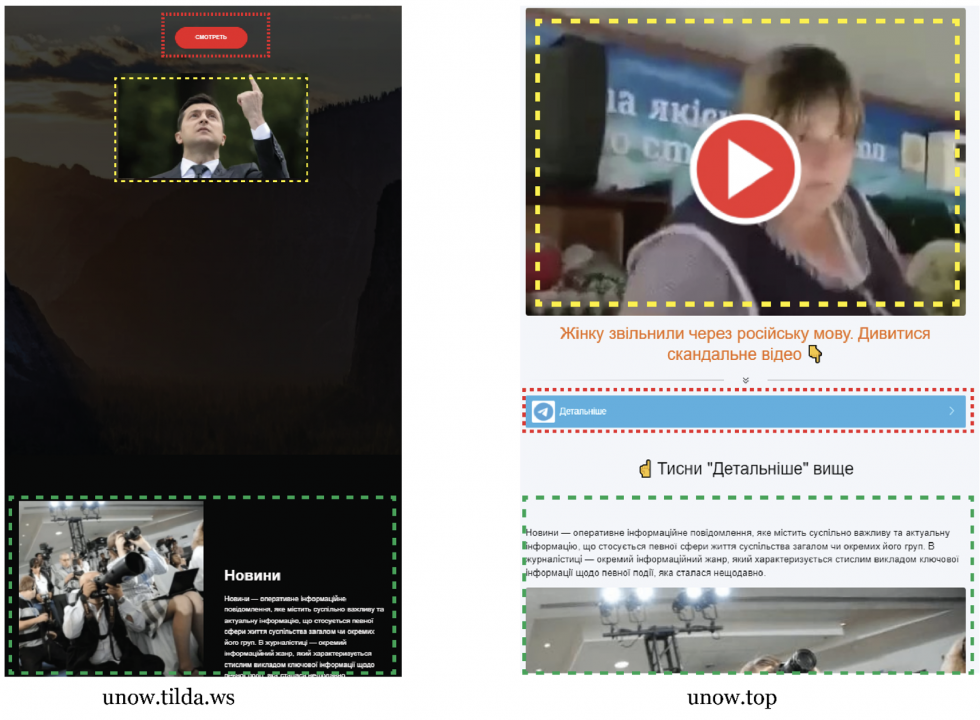

For all of the feeder pages except perepichka.news, the design elements were generic and created either by using Tilda’s website builder, a tool that allows using pre-built blocks for website creation, other similar construction tools, or some combination of the two. (Tilda is a multi-faceted Russian website service. Besides its website construction tool, it also provides free domain hosting services.)

Some feeder pages were also designed to look similar to Tilda’s capabilities but do not bear any evidence that they were created using the tool. There was also a lot of overlap between the design templates, as some nearly identical feeder webpages were designed using both Tilda and non-Tilda templates while providing links to identical posts on the same Telegram channel. For instance, the DFRLab found Tilda and non-Tilda feeder pages that both promoted the Ukraine Now Telegram channel.

WHOIS searches for both Tilda and non-Tilda-designed websites proved fruitless: the Tilda-hosted sites all list Tilda as the registrant, and the non-Tilda websites all had their registrant information redacted.

The ad consistency section of TikTok’s policies also requires the ad’s visual presentation to be consistent with the promoted product or service. While the external webpages linked to from the TikTok ads do not appear to sell any products, they do use clickbait and sensational headlines to make people click through to a related Telegram channel that often does not follow through with the promised content.

The Telegram channels

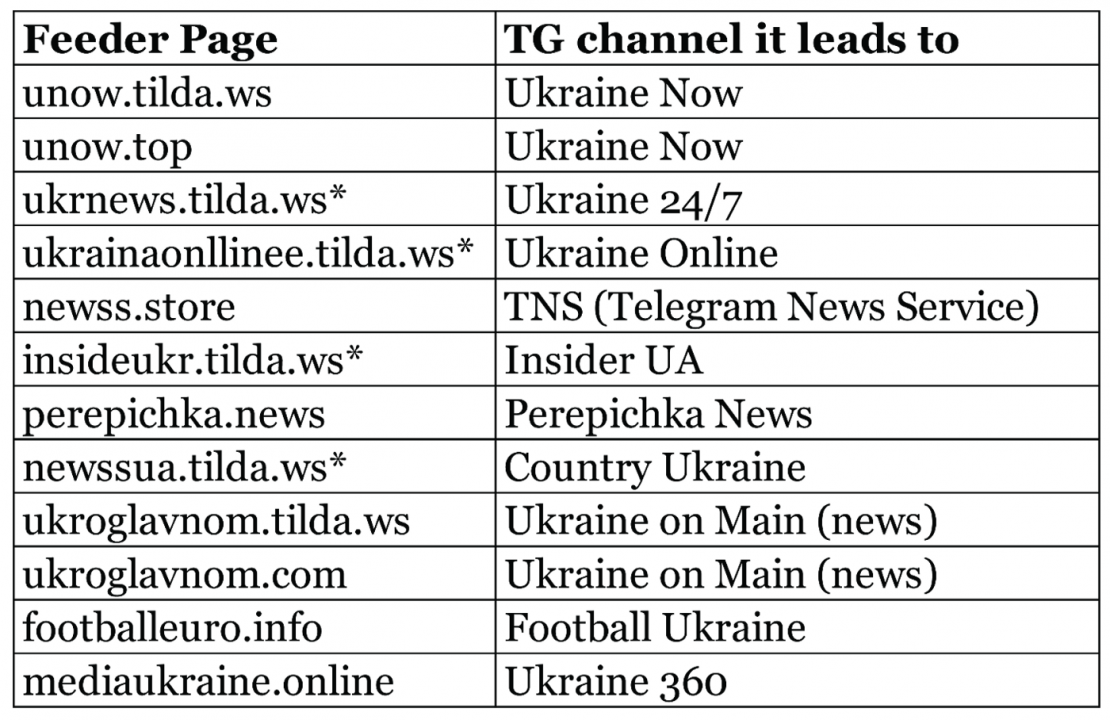

All of the feeder pages funneled traffic to Telegram channels. The DFRLab identified at least 10 such page-to-Telegram pipelines, most of which had names seemingly conveying that the pages and channels were news sources.

At least eight of the Telegram channels ran ads at least one time on TikTok that used feeder pages as a conduit.

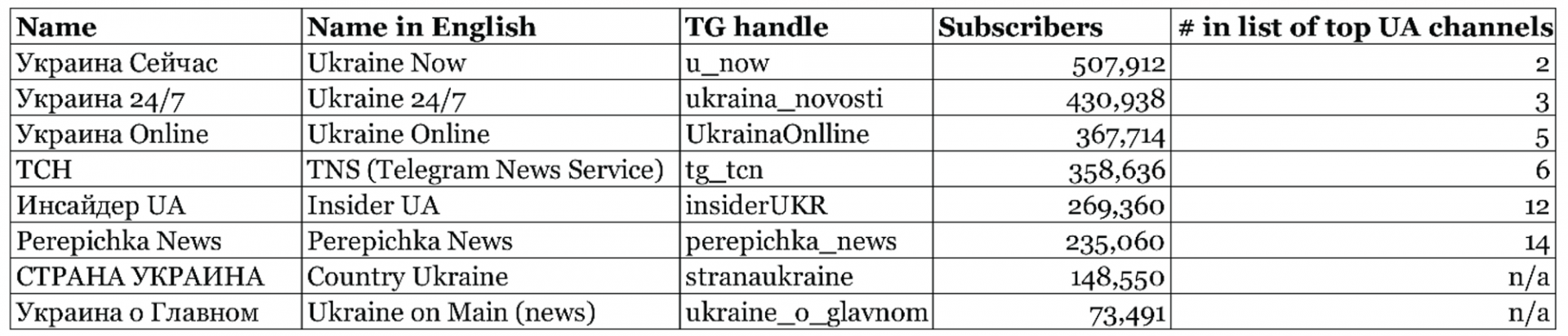

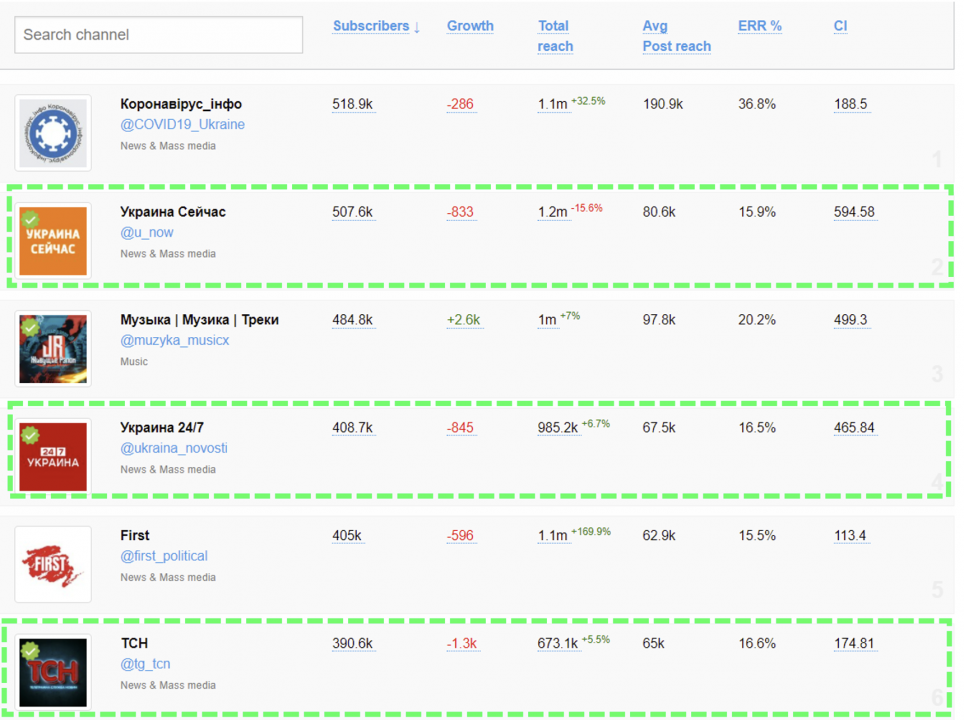

Three of the six most popular Telegram channels in Ukraine in terms subscribership were among those identified, with the biggest one having 507,912 subscribers, according to TGStat, a Telegram analytics tool.

The Institute of Mass Information (IMI), a Ukrainian NGO that implements projects aimed at using mainstream media’s positive impact to foster a robust civil society, recently published an overview of top Telegram channels in Ukraine, including analyzing their content. Based on the simultaneous growth of subscribers, format and style of their posts, and the similarity in content, the organization concluded that Typical Ukraine, Ukraine 24/7, Ukraine Online, and Ukraine Now are parts of the same “holding.”

A look at the Telegram channels’ admins and ad contacts found two digital agencies that proposed services of advertising on Telegram channels identified in this piece.

Most of the channels identified above appear to be part of a larger ecosystem of channel networks, though those networks seem to be administered by different individuals or groups. Moreover, the owner of one of the channels from the list, and one of the wider networks, acknowledged in an interview with Ivan Gul’ that TikTok can be used to increase the number of readers for a given Telegram channel and admitted that some ads are intentionally designed to look like news. He also states both that he pays taxes on revenue from this operation and that none of it is illegal.

IMI also identified a steep increase in the number of subscribers for those channels in July and concluded that it appeared to be an artificial increase of readers. While the DFRLab was unable to corroborate this conclusion, the amplification through TikTok witnessed over the summer of 2021 might explain some proportion of the growth of channels. At the same time, IMI mentioned that only about 15.5 percent of channel have active readers and noted the poor quality of news published on channels.

Promotional content

Content of webpages and social media assets can usually provide some sense of a motive for a given operation. Given that the Telegram channels were the end destination for users, they likely provide the clearest insight into the motive.

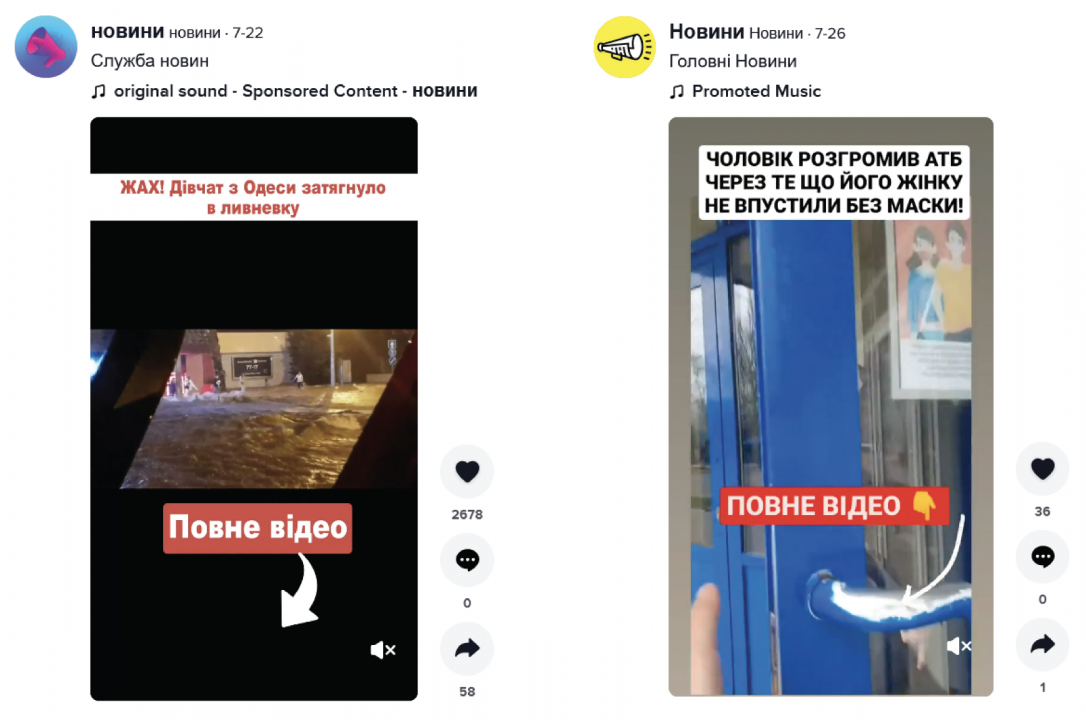

At the front end of the operation, the TikTok advertisements seemed designed mostly to generate clickthroughs to the feeder pages. The TikTok ads often provided some form of sensationalist subject matter to draw the user into clicking through: in other words, clickbait.

The TikTok videos used for promotion usually portrayed the part of the video or screenshot of the shocking news event, like “girls got sucked into sewage” or “guy smashed supermarket after it did not allow his wife to enter without a mask.”

The clickthrough functionality for these videos has since been deactivated, but the posts previously featured links to the feeder webpages usually with the same header. As such, currently available videos on the same channels do not feature any accompanying advertising links.

The feeder page would then push the same or slightly more detailed story, again to trigger a clickthrough. The final destination — the Telegram channel — would often be anti-climactic, failing to provide any deeper context to the clickbait headline. On top of this, the Telegram post being linked to from the feeder page was recursive, prompting a user to click for more information but only leading the user right back to the exact same post.

This process was likely a means of simply driving a user to the channel, theoretically prompting a deeper exploration of the full channel for the sought-for context. Instead, the user would find a channel mixing sensational but ultimately substance-free clickbait, news items pilfered from other more reputable sources, stories boosting the mayor of Kyiv, or what appeared to be sponsored advertising for products like betting services or an upcoming concert event with a link to specific ticketing agency.

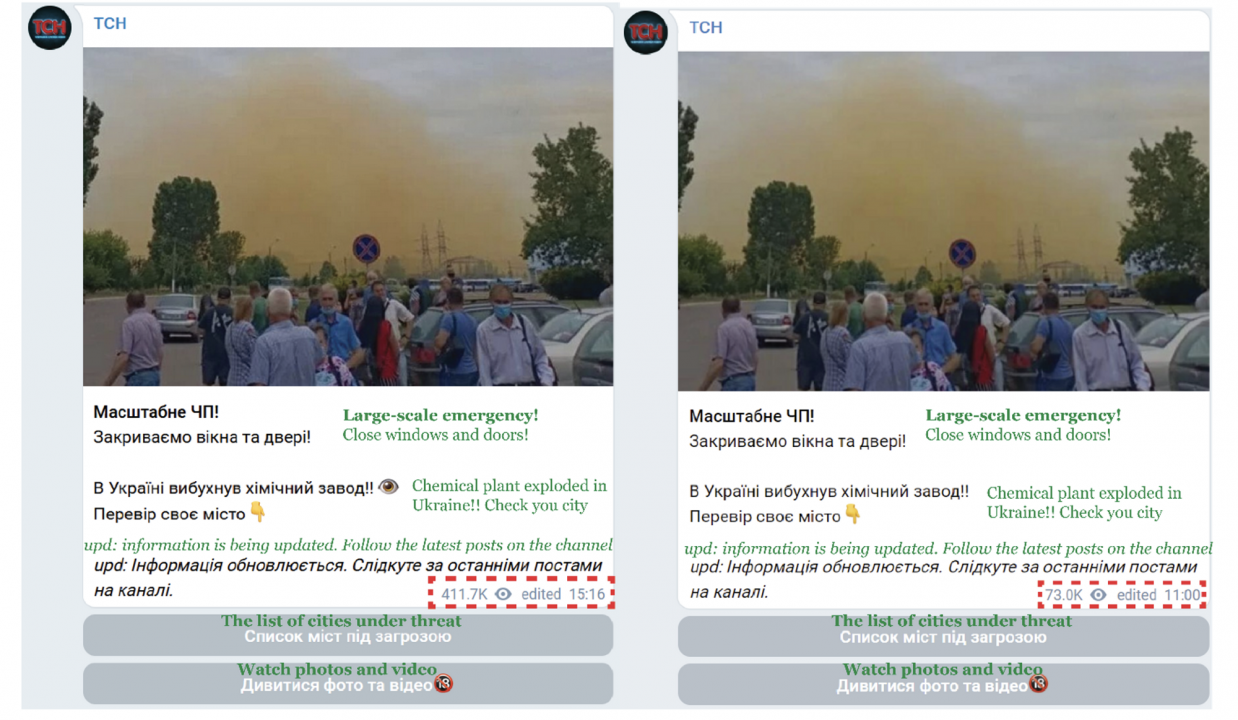

For instance, in July 2021, a feeder webpage linking to the Telegram News Service (TNS) channel reported an explosion at a local chemical plant and suggested that local residents close their windows. While there was an explosion of nitrous gas, the State Emergency Service of Ukraine stated that it did not find any hazardous substances in the air following the incident. Nevertheless, the feeder webpage promoted a post on the TNS Telegram channel with two links that claimed to lead to a list of cities under threat and photos or videos of the explosion. Both links, however, provided no substance beyond a message to “please check later” and “check our other post with a short video,” which itself was only accessible to users who joined the channel. The same post also appeared twice on the channel, first on July 13 and then again on July 18, while the initial explosion took place on July 20. This probably means that the feed was edited to bury clickbait advertising posts under other publications. The page did produce multiple posts on the explosion, but users would need to scroll deep into the channel to find them. (The content of the feeder page and the destination links from it has changed since the time of research.)

As mentioned above, the identified feeder websites appeared highly similar in design; sometimes the differences between the pages were limited to simply using different colors while promoting the same content. And some of that content was lifted verbatim from sources like Wikipedia and posted across multiple feeder pages and Telegram channels.

For instance, several pages featured the same definition copied from the Ukrainian-language Wikipedia entry for “news,” one of which did not even bother to remove the embedded links in the copied text.

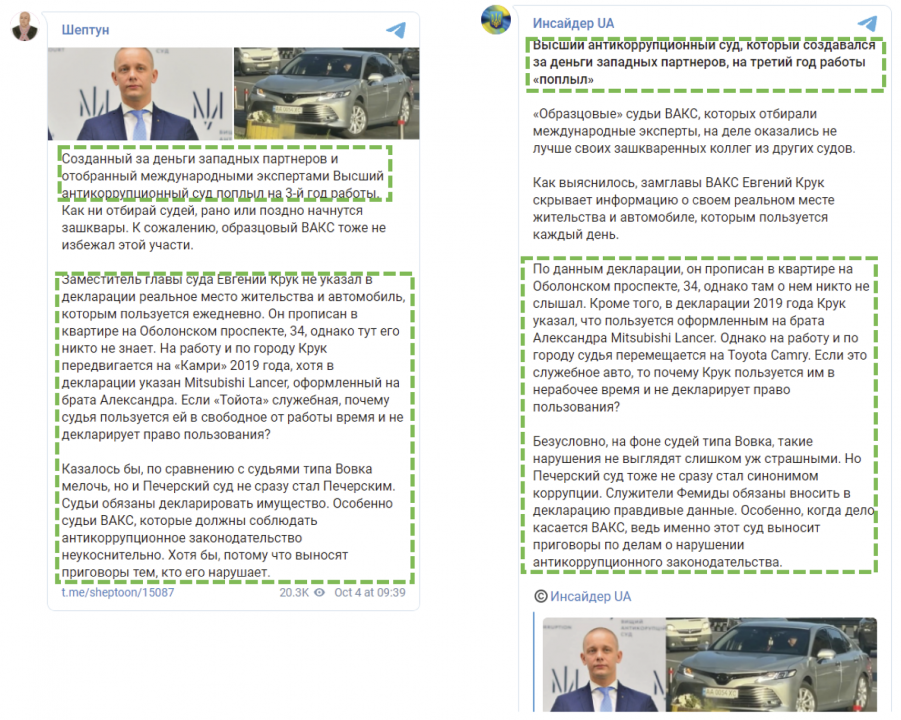

Beyond the clickbait, the identified channels appeared to focus on publishing news primarily copied or adjusted from other sources, usually legitimate mainstream media, regional outlets, or social media posts.

The channels consistently cover emotionally-loaded topics, road accidents, scandals, political surveys results, and links to “rumors” and “inside info” about politicians taken from other channels. The DFRLab previously reported on Telegram channels publishing similar content that broadcast leaks and inside-information about Ukrainian politics that aligned with certain decisions by members of parliament, including the sacking of ministers, previous political scandals.

Some of the channels, however, did participate in specific politician’s promotion by sharing positive news about the political party or its leaders. They sometimes attacked politicians or companies as well.

One of the most frequent topics of posts was embattled Kyiv mayor Vitali Klitschko, who is under fire for his open conflict with President Volodymyr Zelensky’s administration, which he has accused of attempting to “pressure” him following an early morning raid on his apartment block.

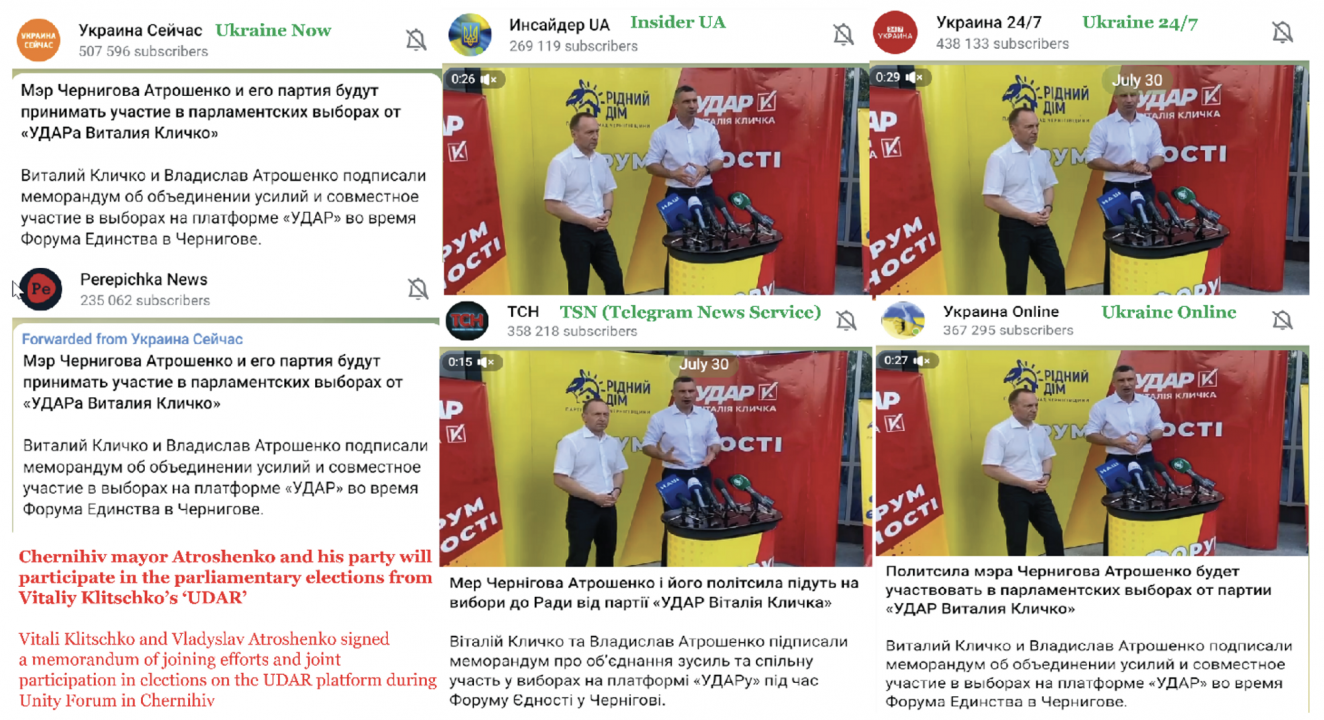

Six of the identified Telegram channels covered Klitschko and his UDAR political party positively by publishing identical stories across the channels. Over a 70-minute period on July 30, for instance, six channels published the same story that the mayor of Chernihiv was joining Klitschko’s political party to run for parliament. Channels used the same visual and text but changed the language of the message (either Ukrainian or Russian) and the headline. Other posts appeared across a number of channels in the same subset but not necessarily all six simultaneously.

The final type of content — providing some evidence of a potential profit motive for these channels — were posts that appeared to be unmarked advertisements. (As declared in the interview with the aforementioned channel operator, some of the ads are explicitly designed to “look like news.”) These ads could be identified by the fact that comments were disabled: i.e., posts of clickbait or news items were open for user comments, while the ads were closed for comment, preventing users from calling them out as advertisements. The ads were also sometimes self-evident, such as when one channel promoted another or pushed services and/or businesses, like betting services.

Beyond the potential connections to the same ad agency, these Telegram channels’ similar technical approaches of using TikTok ads to build their audience, alongside the use of similar generic feeder webpages and often similar content, especially in promoting Klitschko, strongly suggest a certain degree of coordinations. As these channels grow, the operators will be able to raise advertising prices and expand their profits. And perhaps more troubling, they could also employ more deliberately harmful disinformation as clickbait, adding more noise to Ukraine’s politically contentious information ecosystem.

Cite this case study:

Roman Osadchuk, “Popular Ukrainian Telegram channels employ TikTok clickbait scheme to grow audiences,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), October 14, 2021, https://medium.com/dfrlab/popular-ukrainian-telegram-channels-employ-tiktok-clickbait-scheme-to-grow-audiences-5b1b9449b6bd.