Sudanese Facebook network promoting paramilitary group removed month before coup

Inauthentic FB assets linked to Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces operated for years; some admins based in Saudi Arabia and the UAE

Sudanese Facebook network promoting paramilitary group removed month before coup

Share this story

BANNER: RSF General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, aka “Hemeti,” delivers an address in Khartoum, May 18, 2019. (Source: REUTERS/Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah)

In September 2021, one month prior to Sudan’s October 25 military coup, Facebook removed a network of 116 pages, 666 user accounts, 69 groups, and 92 Instagram accounts linked to the country’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group operated by the Sudanese military that actively participated in the coup. Some elements of this network date back to 2013, and others were active up until they were de-platformed in September, promoting the RSF by amplifying RSF statements and pretending to be Sudanese news outlets. According to Facebook, the network was removed for violating the platform’s policy against “foreign or government interference, which is coordinated inauthentic behavior on behalf of a foreign or government entity.” A subset of the pages removed by Facebook featured administrators based in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, both of which have long-standing relationships with the RSF, though the administrators’ identities and exact affiliations remain unknown.

The DFRLab gained access to 92 pages, 574 Facebook accounts, 37 groups, and 77 Instagram accounts after the assets were removed from the platform, as part of its ongoing research partnership with Facebook. Of the 92 pages the DFRLab accessed, 19 had not yet posted any content. Others were completely inactive, having last posted more than a year ago. The pages that were recently active, however, focused on promoting the RSF and presenting themselves as news sources by copying content from legitimate media or repackaging government press releases as breaking news.

Facebook’s removal of the RSF-linked network took place in parallel to the deteriorating political situation in Sudan. In the weeks leading up to the coup, supporters of the military called for the dissolution of the civilian-led transitional government, while civilian officials expressed concern that the military might attempt to take power. And as that takeover played out, according to the Associated Press, “RSF fighters were prominent in Monday’s coup, taking part in arresting [Prime Minister] Hamdok and other senior officials and clamping down in the streets.”

Background

On April 11, 2019, the Sudanese military ousted strongman Omar al-Bashir after months of civilian-led protests represented by a coalition of groups known as the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC). Following the 2019 coup, a Transitional Military Council (TMC) was established under General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. However, protesters demanded the TMC step down and a civilian-led government be implemented. Tensions continued to rise; on June 3 of that year, the armed forces of the TMC, headed by the Rapid Support Forces, massacred unarmed civilians. Al-Burhan is back in charge following the October 2021 coup.

Human rights groups have previously accused the RSF, which was established in 2013 under Sudan’s National Intelligence and Security Service, of committing war crimes in Darfur and during other conflicts. Al-Bashir himself is currently wanted by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide committed in Darfur. Before the military deposed him, the RSF was allegedly employed to protect the al-Bashir from coup attempts.

The RSF is currently led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, more commonly known as Hemeti (“Little Mohamed”), a former ally of al-Bashir who became vice president of the TMC after switching sides and assisting in al-Bashir’s removal from power. Hemeti was also the vice-chair of the joint civilian-military Sovereignty Council, which succeeded the TMC in late 2019 and led the government until the October 25 coup. He is often referred to as the most powerful man in Sudanese politics as he controls a significant portion of the country’s gold mining industry, much of which is sold to the UAE for hard cash, making him one of the wealthiest men in the country.

On October 16, 2021, anti-government protesters loyal to the military gathered outside the presidential palace in Khartoum for a sit-in, calling for the transitional government to be dissolved. The sit-in, organized by members of the new Charter of National Accord that splintered from the Forces of Freedom and Change in recent months, continued over the days leading up to the coup on October 25.

Pro-RSF content

According to Facebook’s September 2021 Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior Report, the network “amplified the official content by the Sudanese Rapid Support Forces (RSF)” and “commentary about RSF and its former head appeared to be among the most common themes in this network’s posting activity.”

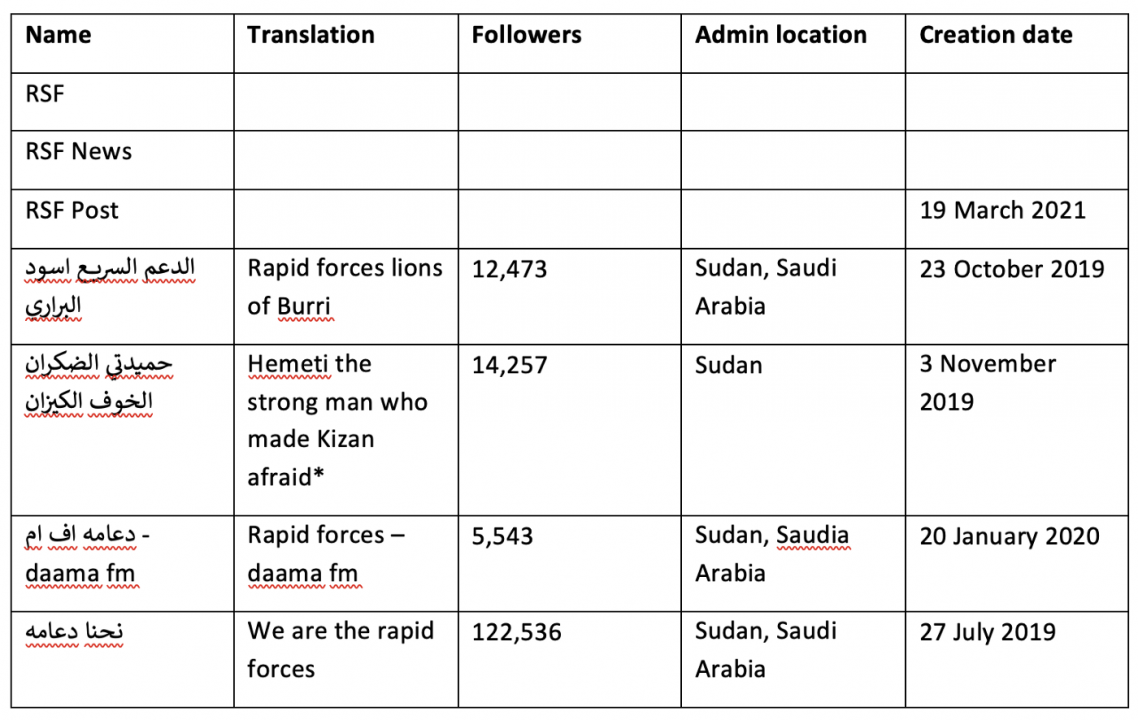

The DFRLab identified hundreds of posts amplifying the RSF and Hemeti, praising the paramilitary group for its work. Included in the takedown were seven pages with the words RSF or references to the RSF and Hemeti in their name. The DFRLab did not have access to the transparency data for all of these pages.

The most active page, نحنا دعامه (“We are the rapid forces”), claimed to be an unofficial page supporting the efforts of the RSF to protect Sudan and the Sudanese people. It consistently posted content supporting the RSF and Hemeti, much of which was copied from RSF press statements. Posts also included images from Hemeti’s verified Facebook page, with captions proclaiming him to be the only hope for Sudan or that he should be Sudan’s ruler.

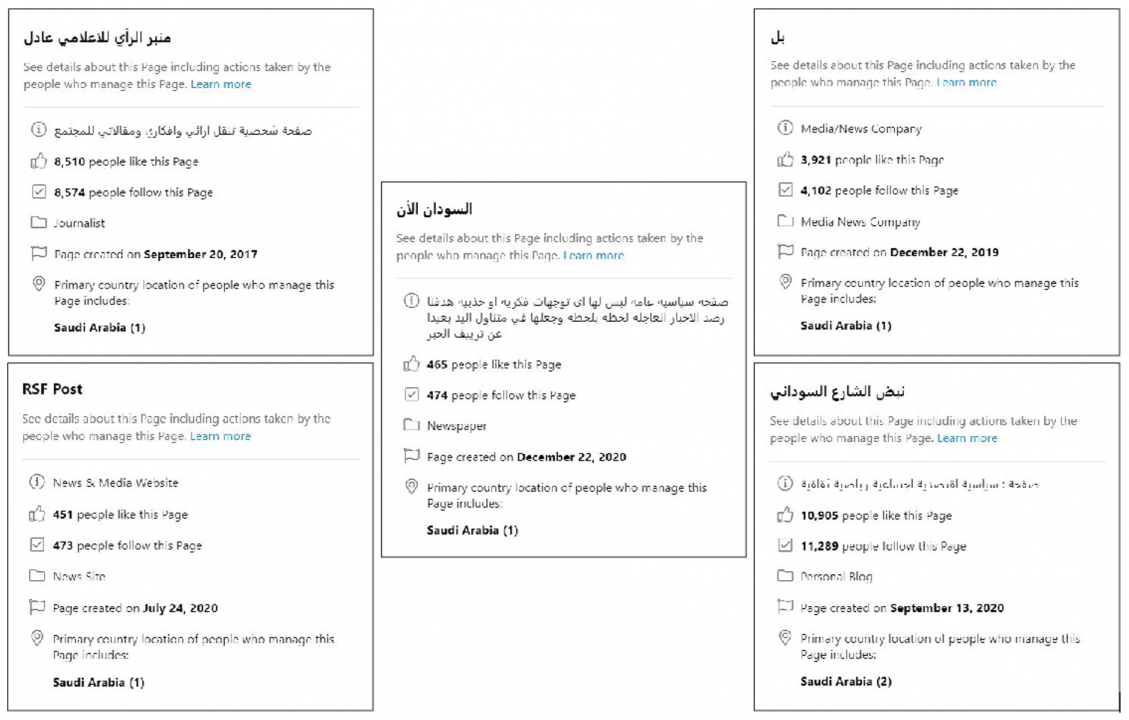

Another page, RSF Post, was administrated by an account located in Saudi Arabia; administrator location data for the pages RSF News and RSF was not available. RSF Post published 22 posts between July 24, 2020, when the page was created, and August 9, 2020, after which the page became inactive. These posts included links to RSF government websites and updates on RSF activities, all posted in English.

The DFRLab had access to the creation dates of 73 pages. Of these pages, only three were created before the April 2019 coup: منبر الرأي للاعلامي عادل (“the opinion platform of the journalist Adel”) in September 2017, ملوك الرومانسية والحنك 100% (“Kings of Romance and flirting”) in March 2014, and شـبـكة صــوت الأمــة (“the national voice network”) in September 2018. At the time of the takedown, all of these pages had been inactive for months.

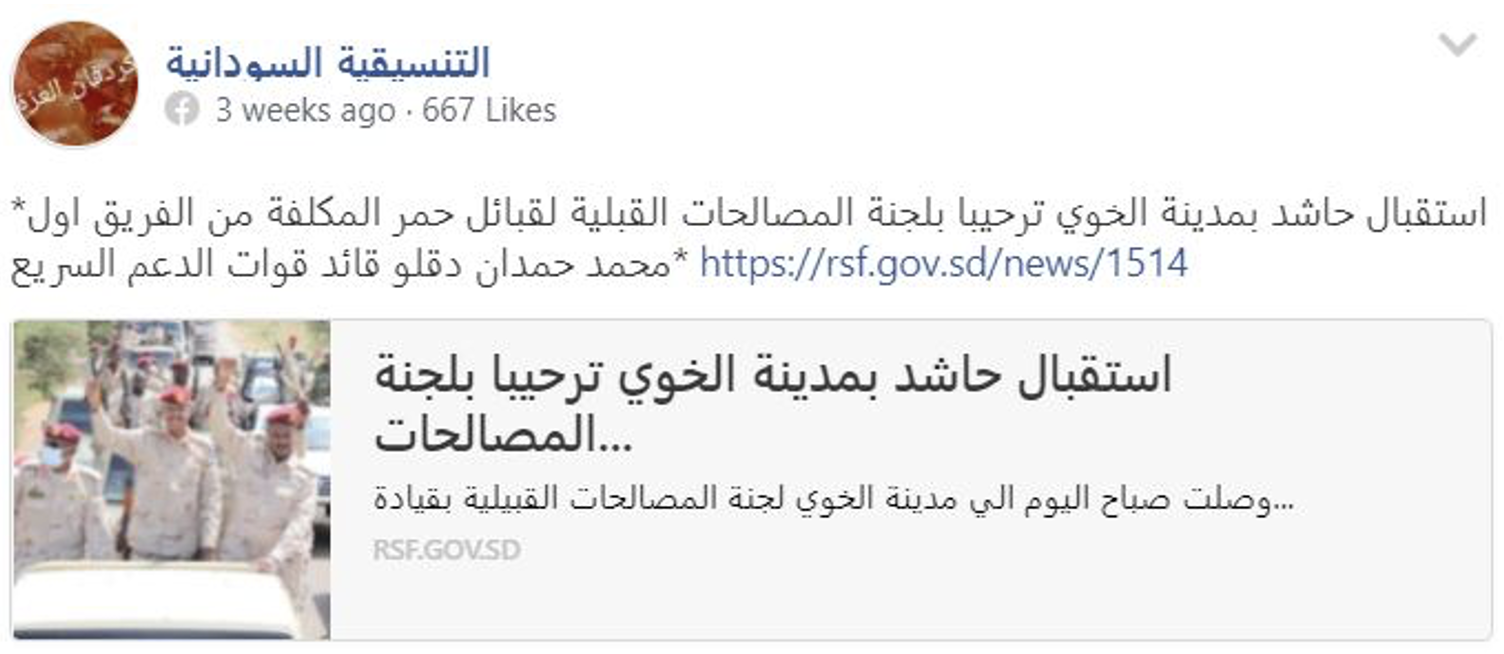

Some of the active pages posted links to the RSF government site, while others copied RSF press releases and repackaged them as news.

One page, named “FFC news,” had nearly 330,000 followers. The page was created in May 2019, after the FFC orchestrated protests that resulted in the removal of al-Bashir, and had admins based in Sudan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The content about Hemeti and the RSF was more subtle than other pages, as it was primarily presented as news. However, the page did post a substantial amount of content relating to the paramilitary group and was not critical of the RSF. This appears at odds with many of the goals of groups who formed part of the coalition, most of which demanded a civilian-led government and were not supportive of the military’s power.

Gulf-based page admins

Of the 92 pages the DFRLab had access to, 35 had administrators located in either Sudan, Saudi Arabia, or the UAE. Five pages, with a combined following of 24,912 user accounts, only had admins based in Saudi Arabia. These pages all claimed to be some form of media. Facebook identifies the primary location of page administrators by analyzing a user’s stated location on their Facebook profile, as well as device and connection information. It is unknown who these page administrators are, or whether they had any connections to other entities in their respective countries.

Under al-Bashir, RSF forces were deployed to Yemen to fight alongside troops from Saudi Arabia and the UAE against Houthi rebels. The move was allegedly paid for by the UAE, and, according to the BBC, Hemeti also provided RSF units to help guard the Saudi Arabian border with Yemen and sent a large force to support the UAE in South Yemen. Anonymous officials claimed that RSF troops started leaving Yemen following the ousting of al-Bashir in 2019, although Hemeti’s relationship with the two countries remains profitable, with most of Sudan’s — and Hemeti’s — gold sold to Dubai, according to a 2019 investigation by Global Witness.

Many of the pages posted positive content about the two countries, including amplifying Hemeti’s role in maintaining the relationship between Sudan and the UAE and Saudi Arabia. However, there was no mention of the relationship between the two countries and the RSF.

Copied Content

Although a significant portion of the pages accessible to the DFRLab were not active at the time they were removed, many of the pages that were active posted the same content.

Four pages, two of which claimed to be media, posted a word-for-word copy of a press release from the RSF on September 29, the same day the press release was posted to the RSF website and official RSF Facebook page. The first of the four pages to repost the press release verbatim did so 13 minutes after the RSF’s official Facebook page itself had published its copy; the three remaining pages posted it within 20 minutes after the first page.

This type of copied content was common among many pages with high follower counts, although the DFRLab could not find evidence of automation as the posts did not appear to be published at the exact same time. Rather, copied posts were published within minutes, hours, or even days of one another, indicating that republishing was likely done manually.

Impersonating media

According to Facebook’s September 2021 transparency report, some of the pages involved in the RSF network “purported to be independent news entities.” Impersonating media appears to be a common tactic seen in Sudanese influence operations, as it is elsewhere. In June 2021, the DFRLab reported on a Sudanese influence operation connected to Russia’s Internet Research Agency that also included a large number of pages claiming to be local media.

In 2019, the Stanford Internet Observatory reported on a Russian-operated campaign that included several high-profile Facebook pages claiming to media. In the 2019 takedown, a page named “Radio Africa,” with administrators in Sudan, Russia, and Germany, had the largest number of followers. Included in Facebook’s recent takedown of RSF-linked assets was a similarly named page, “RadioAfrica-راديو افريكا,” that had only two followers. The DFRLab was unable to prove that there was a connection between the two pages, however.

As with many previous Facebook takedowns, the removed assets copied content from legitimate media in order to make them appear more authentic. Among the assets purporting to be news entities, an Instagram “news” account, “fjajnews,” copied a post from the Facebook page Sudan Plus, which has more than 146,000 followers. The picture from the news piece was cropped to remove the Sudan Plus branding and edited with one of Instagram’s set filters.

The pages also posted summaries of prominent news headlines. The posts would often begin with the Arabic equivalent of “Headline of Sudanese political newspapers.” These posts would often primarily focus on information about the RSF, the Sudanese military, or Hemeti.

According to Reuters, Sudanese citizens with access to the internet, estimated to be approximately 30 percent of the population, “depend heavily on social media for news.” By claiming to be media organizations while pushing content supportive of the RSF, this network had the potential to shift Sudanese support of the paramilitary group in the weeks and months leading up to the October 25 military coup.

The DFRLab team in Cape Town works in partnership with Code for Africa.

Cite this Case Study

Tessa Knight, “Sudanese Facebook network promoting paramilitary group removed month before coup,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), October 28, 2021, https://dfrlab.org/2021/10/28/sudanese-facebook-network-promoting-paramilitary-group-removed-month-before-coup/.