How the Chilean elections unfolded on Twitter

“Far-right” and “far-left” were among the most used terms, with pro-Kast hashtags prevailing.

How the Chilean elections unfolded on Twitter

Share this story

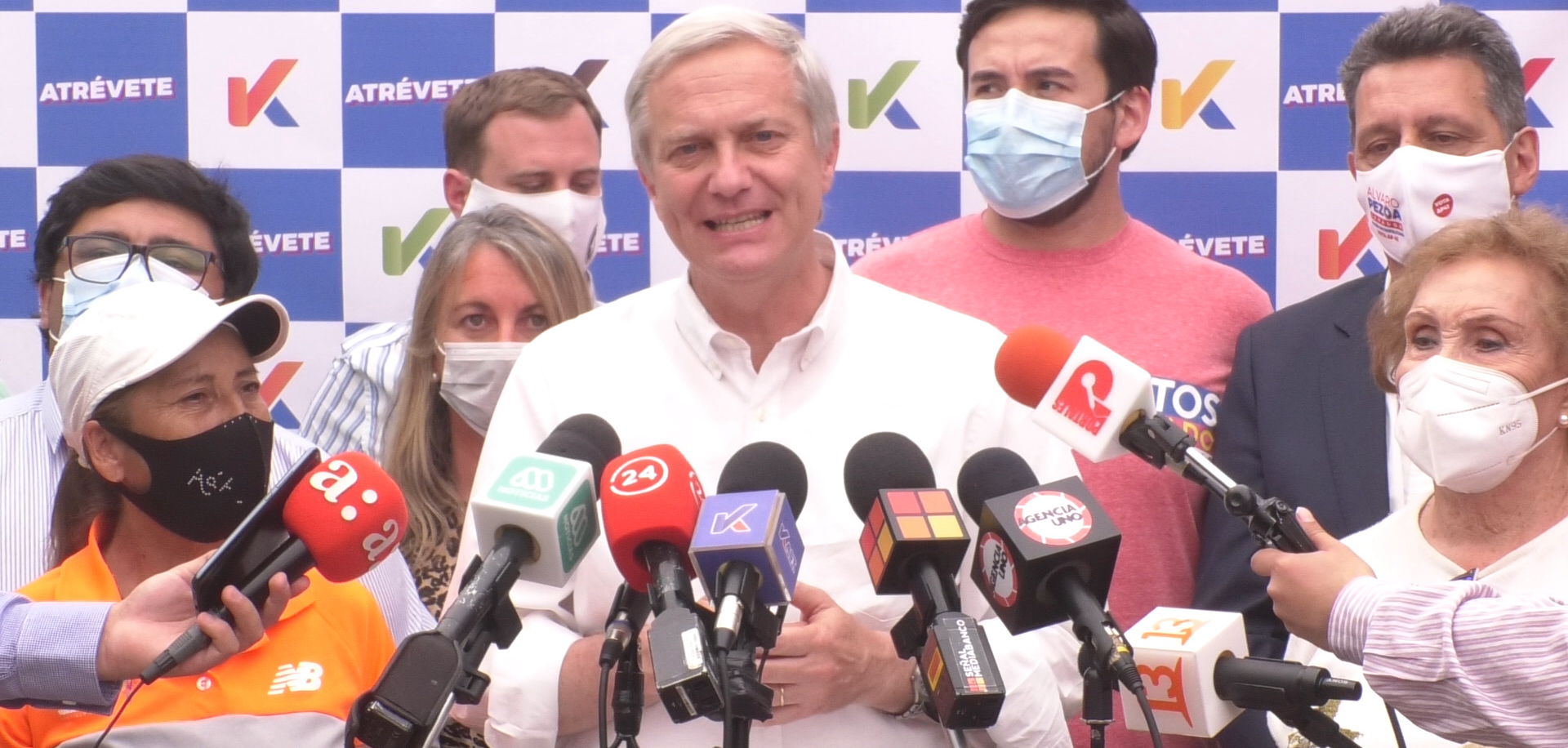

BANNER: Presidential candidate José Antonio Kast speaks at a campaign event on November 2, 2021. (Source: Mediabanco Agencia)

On November 21, 2021, Chile held national and regional elections, including for Congress and a first round for the presidency. José Antonio Kast, representing the right-wing, and Gabriel Boric, representing the left, will face each other in a second round on December 19.

This presidential election is being held while the country is in the process of writing a new constitution that is intended to replace the current one, which dates to the time of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. The Constitutional Convention to draft a new constitution, created after a national plebiscite in 2020, was the most tangible result of the social uprising that started in October 2019 as a protest of pervasive social inequality.

To be implemented, the new constitution will have to be approved in a referendum in 2022, and the new president will be in charge of the transition to the tenets set out by the updated document. While Boric was one of the main articulators of the political agreement that made the Constitutional Convention possible, Kast campaigned for the rejection of the creation of the body in the plebiscite.

The DFRLab has analyzed the broad conversation about Kast and Boric on Twitter to understand how the debate unfolded. Although Twitter is not the most used social platform in the country (used by 31 percent of the population, according to Reuters Digital News Report 2021), the platform attracts politicians, journalists, and other opinion-makers, as in many countries, thus being an important barometer for public debate.

Twitter Trends

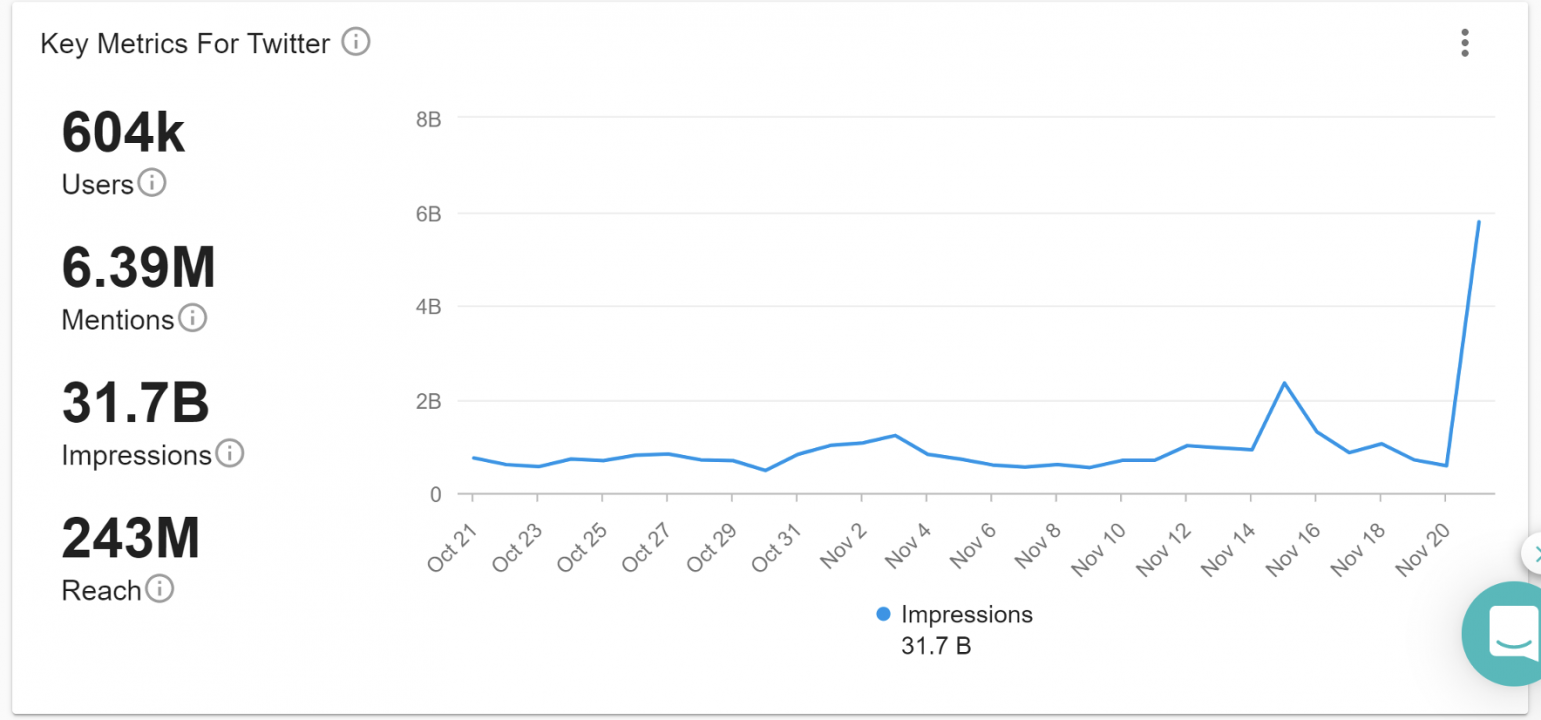

According to a query using social listening tool Meltwater Explore, between October 21 and November 21 (the day of the election), 6.4 million tweets, mostly in Spanish, mentioned “Kast” or “Boric.” The mentions peaked on election day, November 21.

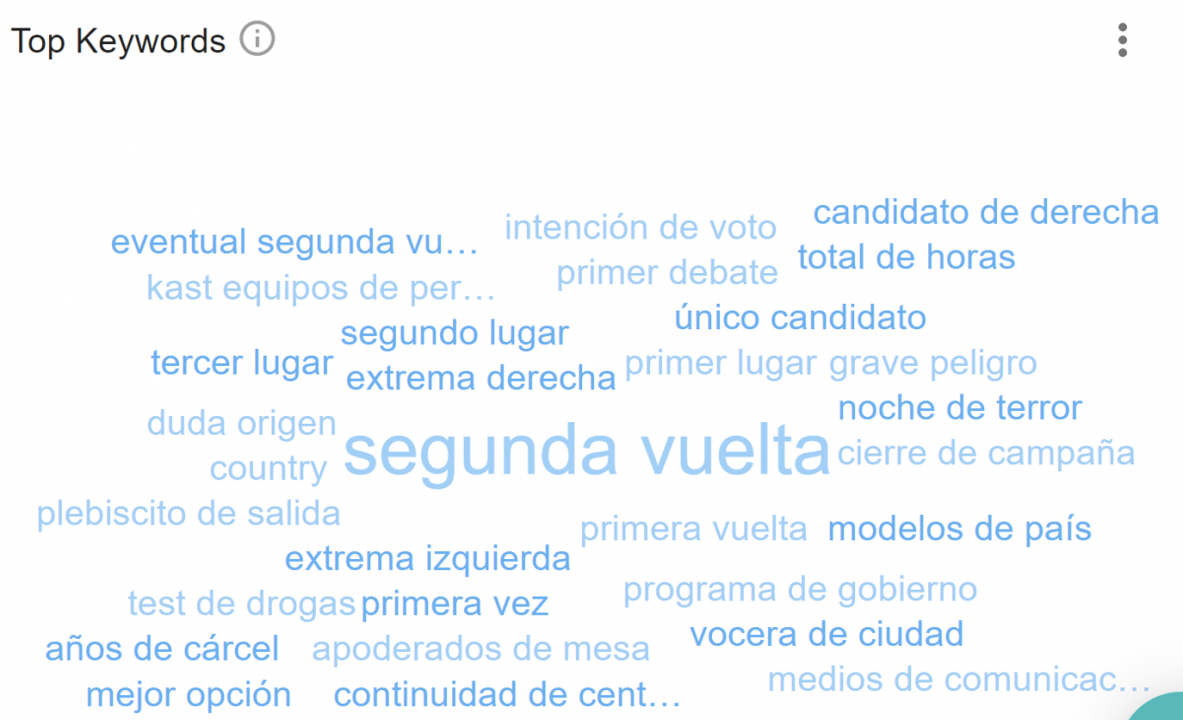

The most-used terms alongside “Boric” and “Kast” were “segunda vuelta” (“second round”) and “primera vuelta” (“first round”), followed by “extrema izquierda” (“far-left”) and “extrema derecha” (“far-right”). This dichotomy underscores one of the most substantial debates around the Chilean elections, that of whether it is a contest between the political extremes. While Kast rejects the term “far-right,” he has expressed admiration of the Pinochet dictatorship and has been described as a far-right candidate by the mainstream international press, including The New York Times, BBC, Time, and The Guardian. Meanwhile, Boric’s coalition includes the support of the Communist Party, which is used as one of the main attacks on his candidacy, though he is not a communist himself. International outlets, including the ones listed above, have described him and his candidacy as “leftist” and “left-wing.”

The most retweeted post using “far-left” denounced use of the term, stating, “Boric is not a communist and is not far-left.” The most retweeted post that mentioned “far-right” criticized Kast’s proposal of creating an “emergency state” in which the president can arrest people in their own houses or in places that “are not prisons nor are meant for detention.”

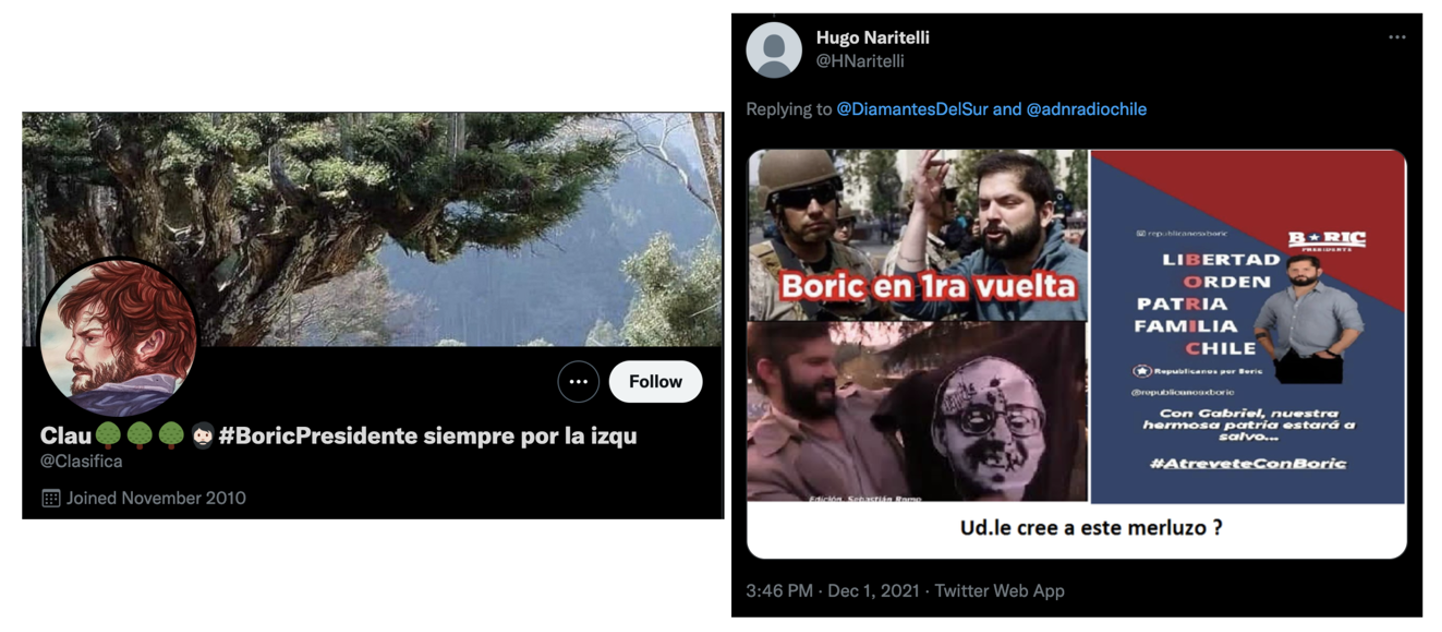

At least one of the top keywords that appeared on Twitter was connected to a disinformation narrative. The expression “Test de Drogas” (“drug test”) first appeared during a presidential debate in which Kast said Boric should take a drug test, without explaining why. The next day, a fake image of a medical record allegedly stating Boric had been admitted to receive treatment for cocaine addiction started circulating on Twitter and Facebook. The information was debunked by fact-checking websites, but its origins are still unknown.

Popular Hashtags

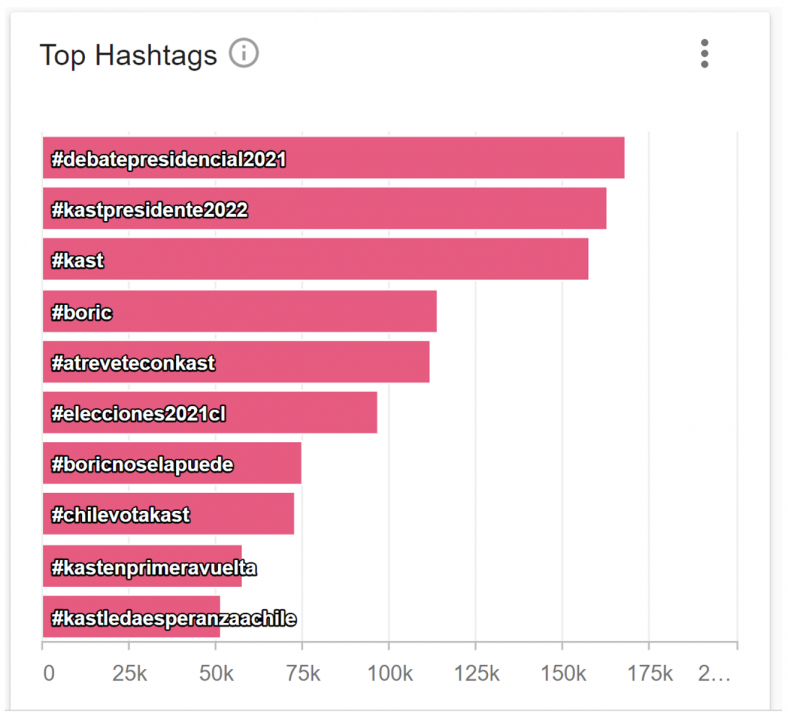

The most used hashtag during the period of analysis was #debatepresidencial2021, in reference to the television debate held on November 15. Among the most used hashtags, two were neutral (#debatepresidencial2021 and #elecciones2021cl), six mentioned Kast, and two mentioned Boric. A closer look at these hashtags revealed that, among those referring to Kast, one was neutral (#Kast) and five were positive. Of the two mentioning only Boric, however, one was neutral (#Boric) and the other was negative (#boricnoselapuede, or “Boric can’t”), suggesting that pro-Kast accounts likely used hashtags more frequently than Boric supporters.

There were signs of hashtag manipulation in the use of the #kastpresidente2022. The hashtag was posted 553,304 times by 36,810 accounts, averaging 15 posts per account. This average is unlikely to have been achieved by such a large number of accounts, suggesting instead that a subset of the accounts posted the hashtag significantly more than 15 times — a common strategy used to give the impression that a topic is more popular than it actually is. For comparison, #debatepresidencial2021 was posted 386,882 times by 126,143 accounts, or three times per account on average, which is more aligned with organic behavior.

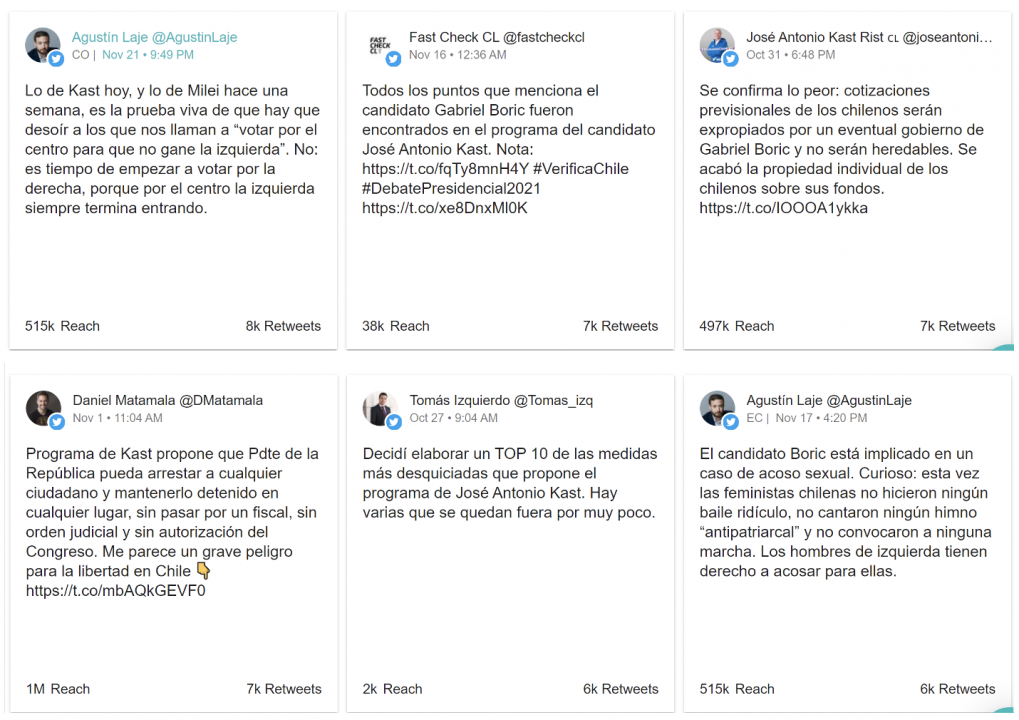

Most retweeted posts

The most retweeted post during the analysis period was by Agustin Laje, an Argentinian conservative influencer who strongly supports Kast and other far-right politicians in the region. In his post, Laje claimed that it was necessary to vote for the right, not the center, to keep the left out of power. Laje also authored the sixth most retweeted post, in which he criticized feminists for allegedly not protesting after Boric was accused of harassment.

The claim referred to an accusation that first appeared during the presidential primaries in July and that was resurfaced by conservative outlet El Líbero weeks ahead of the elections. The person who made the claim said that, in 2012, when he was the president of a student association, Boric made “sexist comments” and gave her “lascivious looks.” The candidate denied having committed harassment but said the claim should be investigated. The victim, however, did not pursue further investigation.

The remaining four tweets in the top six were related to the candidate’s platforms. Three of them referenced Kast’s platform: one was a post from fact-checking organization FastCheck.cl confirming Boric’s claims about the platform and two criticized Kast’s proposals. The fourth was a post by Kast himself in which the candidate claimed that Boric would “expropriate” Chilean’s pension funds if he won, ending the “private property” of their own money. The post referred to Boric’s proposed changes to Chile’s pension system and used polemic language to associate Boric with communism, using terms such as “expropriate” and “private property.” Boric plans to change the country’s pension system, but not in a way that would expropriate any funds. Instead, people that are already in the system would be given the option to remain in the current pension plan.

Chile’s current pension system, implemented during Pinochet’s dictatorship, is fully funded and run by private firms, meaning that each person saves money for their own pension as opposed to a society-wide system. This system has received criticism due to the low payments after retirement — in 2014, a government inquiry found that the median pension was 34 percent of a person’s latest wage, including 24 percent for women and 48 percent for men. Boric wants to replace this system with one in which the funds are publicly administered. The debate around the country’s pension system has been one of the main issues of the protests that have been ongoing in Chile since 2019.

Communities

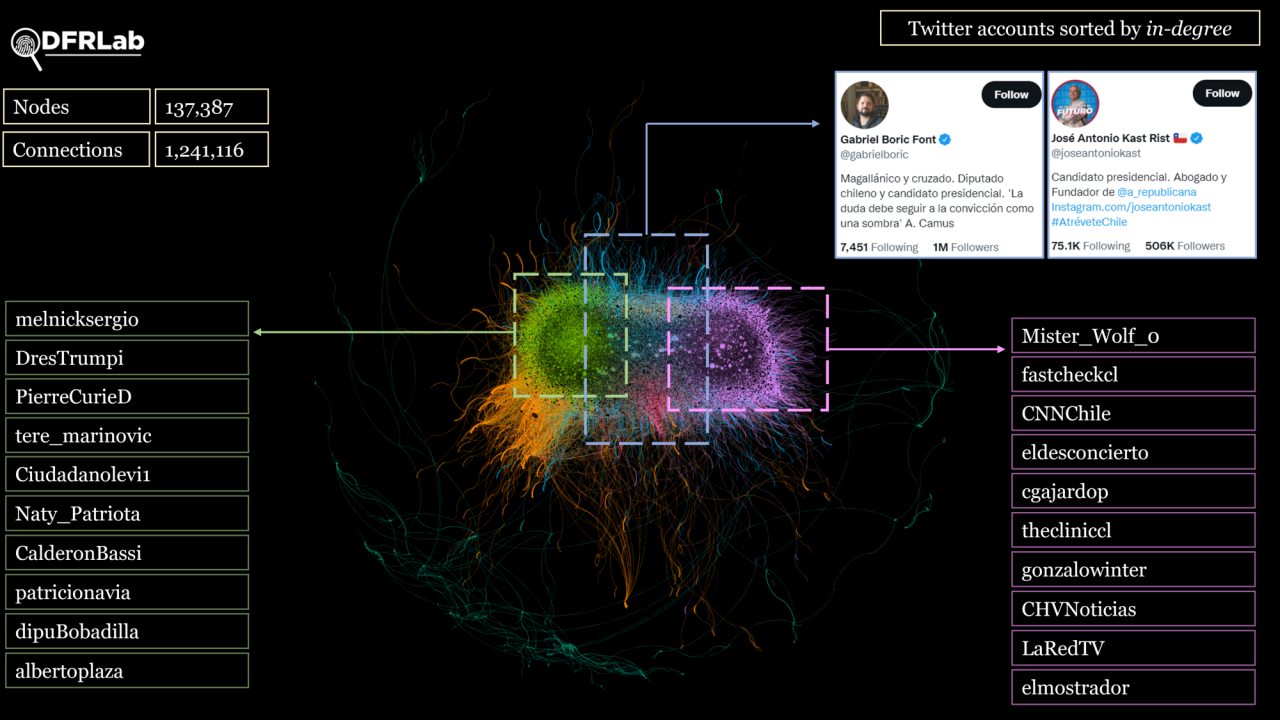

The DFRLab analyzed 1,601,801 tweets posted between November 15 and November 21, the week ahead of the vote, to understand the communities and influencers involved in the debate. Using the social network graphing tool Gephi, the DFRLab then mapped the accounts behind the tweets and the interactions between them — both those interacting with them (eg, their “in-degree”) and their outward interactions (their “out-degree”).

The image below shows the resulting clusters leading the debate. The three primary clusters in green, blue, and purple comprised 80 percent of the traffic under analysis. The accounts — or “nodes,” as labelled in the network map above — that received the most inbound interactions in the green and purple clusters are listed at left and right of the network map, respectively.

The DFRLab then examined the top 20 accounts in the three primary clusters to determine their political sentiment as displayed in their profile descriptions or posts. For example, some accounts overtly declared an affinity with one candidate or the other in their profiles, while others posted content that clearly supported a particular candidate.

The DFRLab found that the top accounts in the purple cluster all appeared to support Boric and received engagement largely from other left accounts; the green cluster was mostly pro-Kast influencers and received engagement mostly from other pro-Kast account.

The most active accounts in the blue cluster also appeared to be pro-Kast but received engagement from accounts on the left and right. Also in the blue cluster were the accounts for Kast and Boric themselves, as well as some other candidates and mainstream media outlets.

Ultimately, it appears that pro-Kast accounts drove much of the conversation, given that they comprised a majority of both the green and blue clusters.

Cite this case study:

Luiza Bandeira and Esteban Ponce de León, “How the Chilean elections unfolded on Twitter,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), December 7, 2021, https://medium.com/dfrlab/how-the-chilean-elections-unfolded-on-twitter-c2436cdb51b7.