Pro-Russian Facebook assets in Mali coordinated support for Wagner Group, anti-democracy protests

Coordinated network promoted military junta in months leading up to France’s decision to withdraw from the country.

Pro-Russian Facebook assets in Mali coordinated support for Wagner Group, anti-democracy protests

Share this story

BANNER: Malians holds a Russian flag and a photograph with an image of coup leader Colonel Assimi Goita during a pro-Malian Armed Forces (FAMA) demonstration in Bamako, Mali, May 28, 2021. (Source: Reuters/Amadou Keita)

A network of Facebook pages promoting pro-Russian and anti-French narratives drummed up support for Wagner Group mercenaries prior to the official arrival of the private military group in Mali. These pages also mobilized support for the postponement of democratic elections following a successful coup in May 2021, Mali’s second in less than a year.

The five Facebook pages, administered from within Mali, present themselves as a mix of charity, nonprofit, and community pages. However, the content shared by the network is aimed at undermining French interests, promoting Russia as a viable alternative to the West, and mobilizing public support for the government of interim President Assimi Goïta and the Malian military. On February 17, 2022, French President Emmanuel Macron announced that French troops would withdraw from Mali.

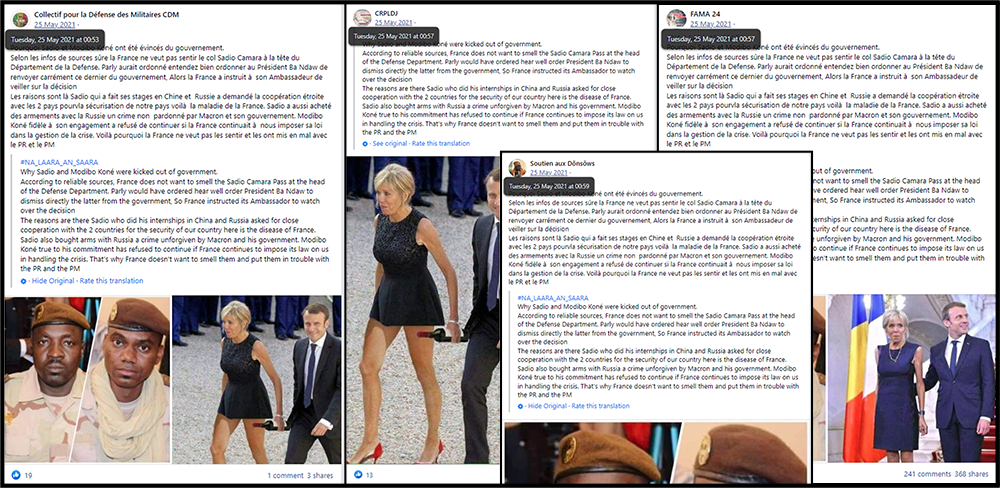

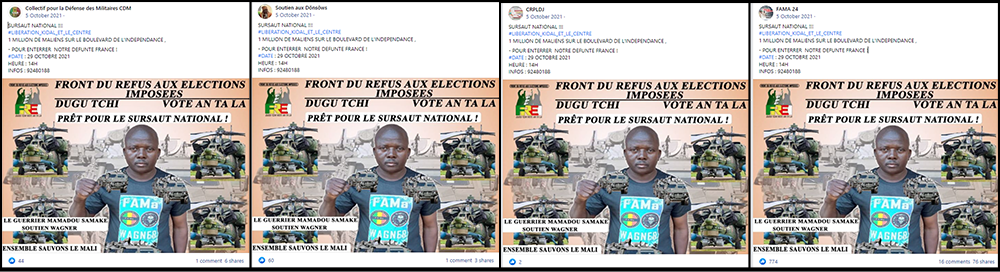

On multiple occasions, these Facebook pages posted content in a coordinated manner across multiple pages. In addition, phone numbers provided as contact details for events organized by the pages provided an additional layer of association between the assets.

In a foreshadowing of the January 2022 coup in Burkina Faso, the network added a new Facebook page focusing on the broader Sahel region in November 2021, which advocated for a “revolution” by the people of the Sahel while amplifying the rest of the network’s pro-Russian and anti-French narratives.

The French-Russian proxy war by social media is not novel in Africa: in December 2020, Facebook removed a French network of 84 accounts, six pages and nine groups that targeted Mali with anti-Russian messages and promoted military interventions in the region in which France participated. At the same time, Facebook also took down competing French and Russian networks that were actively engaging and debunking each other in the Central African Republic.

Background

Mali’s democratic elections, originally planned for February 2022, were postponed in January 2022 for five years, securing Goïta’s rule and prompting the imposition of regional sanctions and a further deterioration of diplomatic relations between Mali and former colonial ruler, France.

Goïta spearheaded two successful coups in less than a year. On August 18, 2020, then-Colonel Goïta and Colonel-Major Ismaël Wagué deposed President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita after months of civil unrest. Bah N’daw, a former defense minister, was elected as interim president in September 2020, with Goïta as vice president. The pair was tasked with overseeing Mali’s transition to a democratic government.

Less than nine months later, on May 24, 2021, Goïta led another coup, prompted by a cabinet reshuffle that saw two of the 2020 coup leaders axed. Mali’s president and prime minister were detained for “sabotaging the transition,” which Goïta promised would proceed as planned during a democratic election in 2022.

In response to the coup, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) suspended Mali’s membership on May 31, 2021, until the promised transition could be concluded. Though ECOWAS initially declined to impose sanctions against Mali, its position changed on January 9, 2022, when it imposed sanctions after Goïta’s government stated that democratic elections would be postponed for another five years.

Rush in, rush out

While political stability remained elusive in Mali, Russia has gradually asserted itself as a viable alternative to France. Since 2014, France has provided military support in the Sahel region through Operation Barkhane, and before that indirectly through the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), the United Nation’s third largest peacekeeping force.

Relations between France and Mali came under pressure in May 2021, when France criticized Goïta’s second coup. In turn, rumors –also promoted by the pages in the network DFRLab identified — suggested France had a hand in N’daw’s cabinet reshuffle and had hoped to remove the two former coup-leaders because of their ties to Russia.

When reports surfaced in September 2021 that Mali intended to strike a deal with the Wagner Group, the Russian private military contractor with extensive links to Putin associate Yevgeny Prighozin, relations deteriorated even further. Mali denied any association with Wagner mercenaries.

On December 24, 2021, several countries with peacekeeping forces in Mali, including France, Canada, and Germany, condemned the deployment of Wagner Group mercenaries in the region. On January 7, 2022, the spokesperson for the Malian army denied the presence of the Wagner Group but confirmed that Russian instructors had taken over a base near Timbuktu abandoned by the French. On January 11, France24 published video footage of suspected Russian mercenaries in the town of Segou.

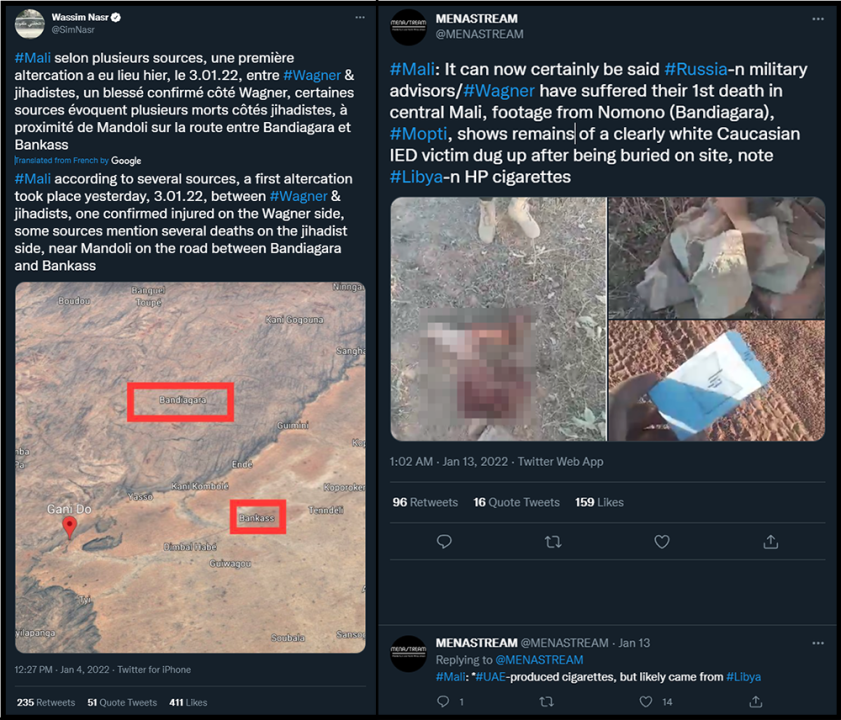

Although Bamako denied that presence of the Wagner Group and insisted that “Russian military instructors” were deployed as part of a bilateral agreement with Russia, an unconfirmed report on January 5 claimed a Russian mercenary had been injured during a clash with insurgent forces near Bandiagara.

This is reminiscent of events in the Central African Republic, where Russian military instructors, ostensibly deployed as trainers, engaged in kinetic deployments and were accused of committing torture in a UN report.

Boots on the ground

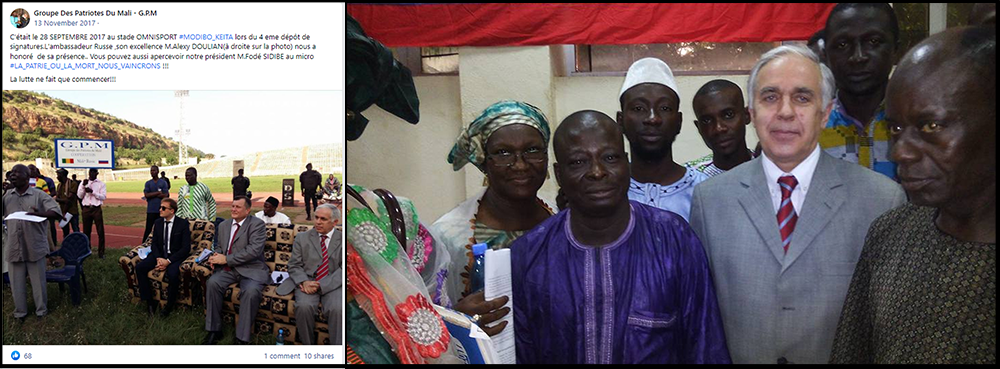

By the time France criticized Goïta’s 2021 coup, the groundwork for increased Mali-Russia cooperation and resistance to the French had already been laid. As far back as September 2017, a civil society organization called the Groupe des Patriotes du Mali (“Group of Malian Patriots,” or GPM) and its leader Mahmoud Dicko pushed for more cooperation between Russia and Mali. Dicko canvassed communities, collecting signatures in support and recording his visits, and secured the attendance of Russian ambassador Alexei Doulian at several gatherings held by GPM. Photographs of these events were published on two Facebook pages created by GPM in January 2017 and July 2019.

Another civic organization, Yerewolo debout sur les remparts (“Unerringly Standing on the Ramparts”), surfaced in January 2020, with an apparent agenda of advocating for the disengagement of French and UN troops in Mali. Before Yerewolo established its own social media presence, GPM amplified its protests; GPM banners were also frequently sighted at Yerewolo protests, and vice versa.

The Kremlin took notice. In addition to Russia’s then-Ambassador to Mali Alexei Doulian attending GPM gatherings, Russian Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Maria Zakharova referred to the GPM during a weekly briefing in April 2019. In August of that year, Doulian accepted a petition from GPM containing 8 million signatures of “internal and external” Malians supporting Mali-Russia cooperation.

Content

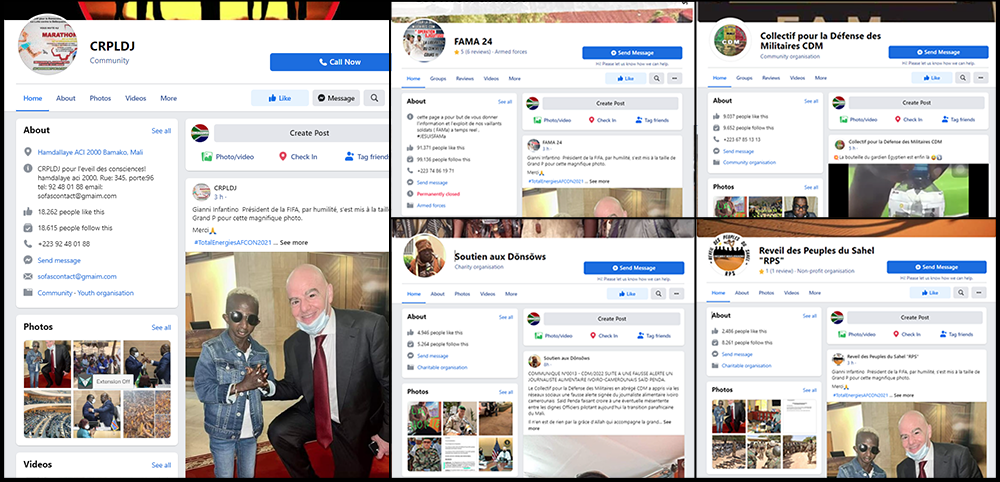

Within this context, the DFRLab identified a coordinated network of five pages that shared narratives that promoted Russian interests while disparaging the West, and France in particular. At the time of publishing, the pages have a combined following of more than 140,000 accounts, having published nearly 24,000 posts in total. Two of the pages were overt in their support for the Malian armed forces (Forces Armées Maliennes, or “FAMa”).

The largest page in this network, FAMA24, had garnered more than 90,000 followers at the time of publication.

From a content perspective, the pages shared familiar narratives promoting Russia and denigrating France and the United States. The content shared by these pages supported Russian interventions in Mali and supported cooperation between the Goïta government and the Kremlin.

In September 2021, when news first broke that Mali was considering making use of Wagner mercenaries to bolster its military capacity, the pages within this network began promoting Wagner as an alternative to French soldiers. Memes depicting Wagner as battle hardened soldiers replacing French soldiers were shared on these pages. Calls for cooperation between Wagner and the Malian military were also rife.

The network also shared content calling for the boycott of French companies and media. Calls to cancel the media accreditation of French media outlet RFI spread on these pages, to which Mali’s Minister of Communications later issued a response.

In November 2021, a page focused on the broader Sahel region joined this network and immediately began coordinating some of its posts with the rest of the pages. One page, Reveil des Peuples du Sahel (RPS), focused on the “liberation of the Sahel people,” paying special attention to Niger and Burkina Faso. While administered from Mali, the page echoed the same Sahel-wide narratives, including support for Wagner and the region’s liberation from the French.

Coordination

The oldest page in the network was created on February 20, 2015, although its first coordinated post only took place on February 2, 2020, less than a month after the FAMA24 page was created. Subsequently, each of the new pages that joined the network coordinated a post within hours of being created.

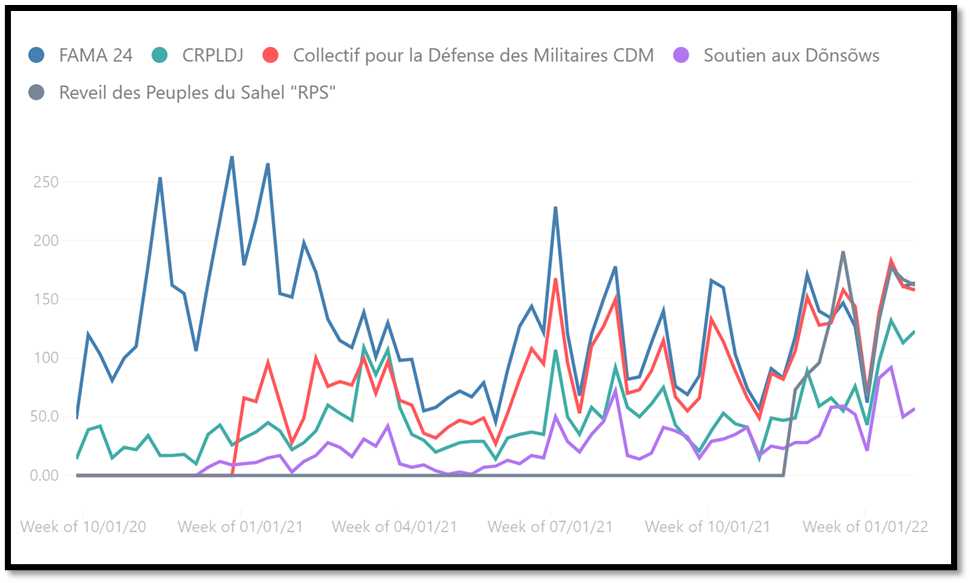

This coordination is clearer when comparing post-counts from pages in the network over time. Although the more active pages shared unique content independently, the relative post-counts for each of the pages showed a congruence in their activity.

Using data from CrowdTangle, the DFRLab calculated the difference in timing of posts between the pages in the network. Out of a total of 23,685 posts reviewed by the DFRLab, more than one-third of them (approximately 8,850) were posted within 60 seconds of each other.

The coordination becomes apparent when the data is visualized. Pages within the network posted the same or similar content within seconds of each other, often less than 20 seconds apart.

Phone numbers

In addition to the coordinated posting times, posts by the pages in the network identified several Malian telephone numbers that were provided for information hotlines or for ordering FAMA-related merchandise. The overlapping use of these numbers further indicates that the administration of these pages was connected.

For example, on March 18, 2021, the CDM, CRPLDJ, and FAMA24 pages posted an image arranging for a memorial gathering for fallen FAMA soldiers. The post, created using the CDM logo, included the same

two contact numbers.

An overlapping number ending in 88 also appeared on the CDM Facebook page, and was used by the pages FAMA24 and CRPLDJ to promote the CDM page shortly after it was created. The second number, ending in 13, is displayed as the contact number on the CRPLDJ Facebook page and has been used in CRPLDJ communications since at least February 2019, when it was used to arrange a blood drive and marathon.

Importantly, the number ending in 88 was also used to promote the FREI, a nongovernmental organization that has advocated for the postponement of democratic elections in Mali since September 2021. Although the FREI has no social media presence of its own, the pages in this network amplified its events and co-hosted press releases together.

This was not the last time that these organizations would collaborate in staging protests. Following the imposition of sanctions against Mali’s military-led junta for postponing democratic elections for five years, the pages in this network pushed for wide-scale protests in the capital. An FREI spokesperson provided on-the-ground coverage of the event, which the Facebook pages in this network subsequently amplified.

These organizations came full circle, as several posts on the pages in this network amplified Yerewolo’s events; however, there was no evidence of a closer association than the groups sharing mutual objectives.

Conclusion

In many African countries, civil society and nongovernmental organizations are vital to fill the gaps left by regime changes and under-resourced governments. In Mali, however, some of these organizations have been involved in pro-Russian and anti-French campaigning for months, drawing on the Central African Republic as an example of international cooperation without the West.

A part of this played out on Facebook using coordinated tactics, some of which actively advocated against democratic reforms since September 2021. The diffusion of these narratives into the rest of the Sahel region is already apparent, as can be seen in our parallel investigation on the rise of pro-Russia support in Burkina Faso.

Cite this Case Study:

Jean Le Roux, “Pro-Russian Facebook assets in Mali coordinated support for Wagner Group, anti-democracy protests,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), February 17, 2022, https://medium.com/dfrlab/pro-russian-facebook-assets-in-mali-coordinated-support-for-wagner-group-anti-democracy-protests-2abaac4d87c4.