China spearheads social media campaign to attack civil society in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe’s ruling ZANU-PF party targets opposition figures with Chinese government assistance.

China spearheads social media campaign to attack civil society in Zimbabwe

Share this story

BANNER: Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa and Chinese President Xi Jinping attend a welcoming ceremony before talks at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, April 3, 2018. (Source: Reuters/Thomas Peter)

Over the last several years, China has greatly expanded its investment in media abroad. From engaging in content-sharing agreements with local newspapers, to purchasing stakes in private media outlets, to expanding its network of foreign correspondents, China’s efforts in external propaganda have shown rapid growth year over year.

The impacts of Chinese investments in some regions of the world are far-reaching. A September 2022 report by Freedom House charts the effects of China’s media push in democratic countries across the globe, with different countries showing varying degrees of resilience to Chinese Communist Party (CCP) influence. However, the effects of China’s efforts are perhaps even more significant in countries where civic freedoms are already highly restricted, further entrenching authoritarian regimes by lending institutional power to legitimize the state and silence calls for democracy.

Recent events in Zimbabwe illustrate the potential impacts of China’s media influence in countries where civic freedoms are already limited.

Zimbabwe’s media environment is highly controlled by the state; Reporters without Borders ranks Zimbabwe at 137 out of 180 countries surveyed in terms of media freedom and protection. State-owned papers in Zimbabwe are often highly supportive of China. The ruling political party, Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU–PF), has used its influence over state-controlled papers to attack civil society groups, journalists, and activists who have criticized Chinese business operations in the country, using such criticism as a rationale for engaging in political persecution.

Traditional media

The state-controlled organization Zimpapers operates the Zimbabwe Herald, one of the country’s leading newspapers by circulation numbers, which often uses its power to support the ruling ZANU-PF party. Ahead of the 2021 presidential election, for example, the head of Zimpapers requested that the organization’s media editors use their outlets to encourage readers to support ZANU-PF candidates. ZANU-PF also has a close relationship with Beijing, as China is one of the few investors in the country due to existing Western-led economic and political sanctions. Reports in 2013 and 2014 alleged that Chinese state entities bankrolled ZANU-PF candidate Robert Mugabe’s presidential re-election campaign.

There is a symbiotic relationship between Harare’s control over the media environment and Beijing’s desire to spread its message. State-approved journalists have been invited to China to attend training seminars, and China has donated computers and other equipment to the Herald. In 2021, the state-run television network produced a documentary praising China’s vaccine contributions, with the Chinese ambassador to Zimbabwe giving remarks in the documentary. The Herald also cited Chinese election observers to legitimize the country’s troubled electoral process; for example, on the day of the 2013 election, the Herald ran a story reporting that Chinese election observers had dismissed accusations by the opposition MDC-T party that the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission rigged the election in favor of Mugabe and ZANU-PF.

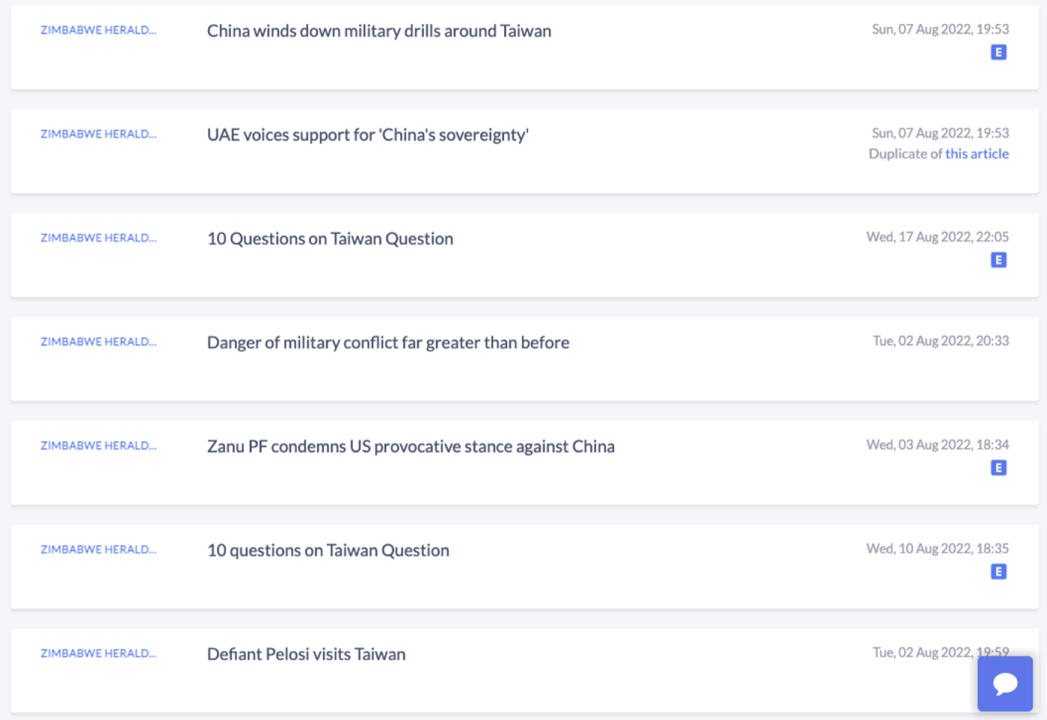

More recently, following Nancy Pelosi’s August 2022 visit to Taiwan, the Herald ran a total of thirty-two articles that month supporting China’s “One China” principle and condemning the visit as a US provocation. In contrast, the Herald ran zero articles addressing the Taiwan situation in July and September. The blitz of Taiwan coverage in the Herald follows similar patterns in China’s overseas media activities for the month of August.

The Herald also spreads anti-Western narratives about the war in Ukraine that are also supported by China, including claims that NATO expansion caused the war; conspiracy theories that biolabs in Ukraine were potential sources of the COVID-19 outbreak; and that Western criticism of Chinese human rights policies is “fake news” designed to “smear” China. Chinese state media often recycles Herald stories in its own content, depicting China-supplied narratives as original reporting from Zimbabwe. Similarly, Chinese state media content is disproportionately represented in local news environments, muddying the waters for local media consumers to distinguish between state propaganda, content from news-sharing agreements, and independent news reporting.

In addition to content-sharing, state-controlled media outlets in Zimbabwe have also attacked civil society actors and other independent media organizations that criticize Chinese business operations in the country for polluting the environment and treating locals poorly. In one well-publicized account, ZANU-PF leveraged state-owned media to accuse independent newspaper The Standard and several NGOs that had criticized the Chinese government of being part of a United States-funded campaign to undermine the Zimbabwean government. The Herald claimed that the US State Department funded the campaign and that the US embassy was working with the opposition party Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). The article also suggested the US and MDC pay local journalists $1,000 per pitch to develop unfavorable stories criticizing China for “violating community and human rights” on both news and social media platforms.

The US embassy in Zimbabwe pushed back against the article. “An independent press is essential for democracy to flourish. #JournalismIsNotACrime,” it stated in a Twitter thread. The embassy continued: “We routinely provide training and U.S. exchange opportunities to journalists and other professionals in Zimbabwe and around the world to build expertise and relationships.”

Social Media

China has also used social media platforms to spread its messaging. On WeChat, the Zimbabwe Chinese Network — an online WeChat page geared towards Chinese citizens in Zimbabwe who are engaged in business activities in the country — published an announcement warning the local Chinese business community, “The United States is trying…to incite, instigate, and even bribe some anti-China forces, individuals, and media…to deliberately slander [China]…and incite the masses…to carry out anti-China activities.” The Twitter account for the Chinese embassy in Zimbabwe also published tweets claiming that local NGOs were being paid by the US to undermine China-Zimbabwe relations, and by extension, the Zimbabwean government. A campaign using the hashtag #Mr1k (referring to the alleged $1,000 per pitch the US supposedly paid for negative China stories) attacked Zimbabwe-based NGOs and journalists for undermining Chinese businesses, claiming they were paid agents of the US.

In one tweet, the account of the Chinese embassy in Zimbabwe described news reports by independent local media outlet the Standard as “fake news,” and linked to an article from the Herald.

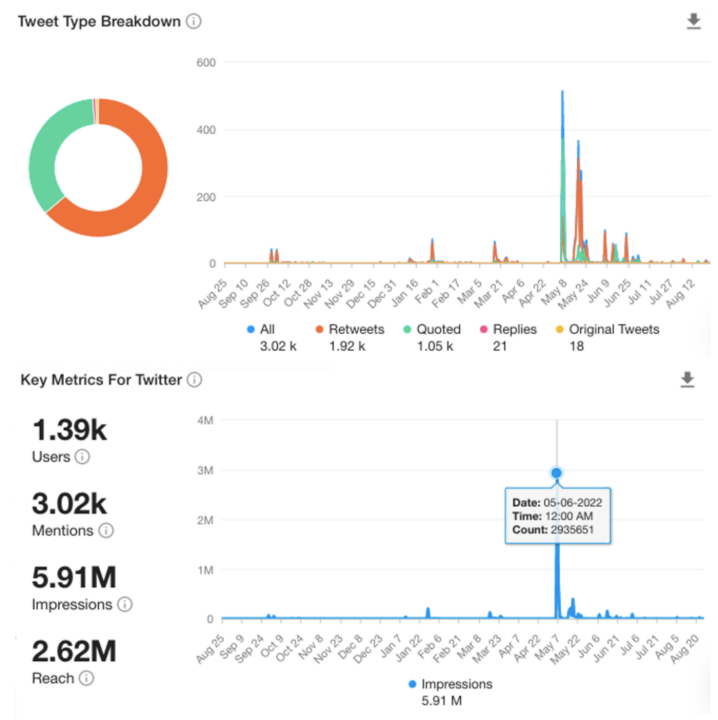

The #Mr1k hashtag peaked on May 6, 2022, the same day that the Crisis in Zimbabwe Coalition, a conglomeration of more than seventy civil society groups focused on democracy promotion in the country, issued a letter criticizing what they described as China’s exploitative business practices. Over the course of a year beginning in August 2021, the hashtag garnered 5.91 million impressions and reached 2.62 million Twitter users. Retweets comprised nearly two-thirds of hashtag mentions.

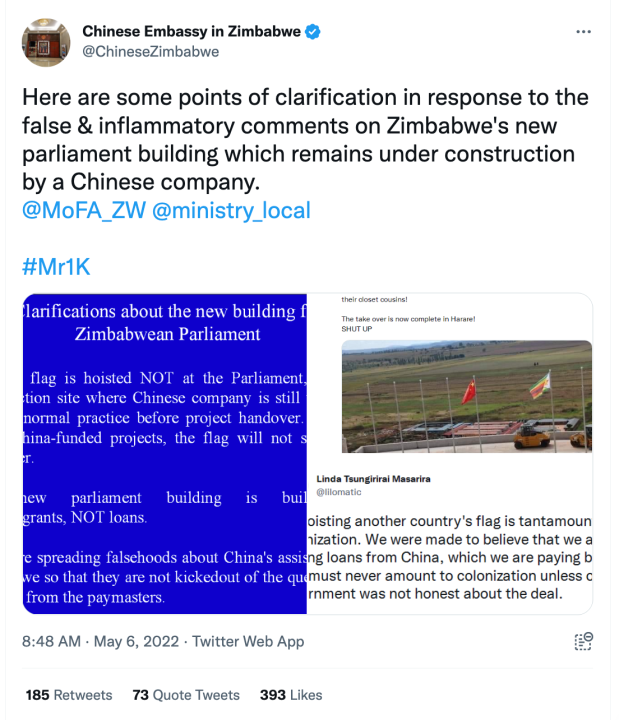

A tweet from the Chinese embassy in Zimbabwe’s Twitter account published on May 6 received the highest number of engagements of all tweets utilizing the #Mr1k hashtag, garnering 185 retweets, 73 quote tweets, and 393 likes. The tweet included “points of clarification” about China funding the construction of Zimbabwe’s new parliament building, and accused opposition journalists of “spreading falsehoods about China’s assistance to Zimbabwe so they are not kicked out of the queue for a handout from the paymasters.” These accusations of foreign funding provide political cover for the government to crack down on civil society actors.

The tweet directly targeted two prominent Zimbabwean opposition figures: Hopewell Chin’ono and Linda Tsungirirai Masarira. Chin’ono is an independent investigative journalist who has been arrested numerous times by the Emmerson Mnangagwa administration, most recently in January 2021 for “communicating falsehoods.” Chin’ono previously expressed fear for his life following a June 2020 press conference in which a ZANU-PF spokesperson publicly attacked him for undermining the integrity of the first family by exposing corruption. Linda Tsungirirai Masarira is a politician and activist who served as a spokesperson for the opposition MDC-T party and previously organized hashtag opposition movements against the late former president, Robert Mugabe.

Several pro-government Twitter accounts routinely retweeted the Chinese embassy account and promoted the #Mr1k hashtag. For example, the pro-ZANU-PF Twitter account @cry_gurende, which sometimes issues tweets attacking journalists investigating the Mnangagwa regime, retweeted the Chinese embassy’s May 6 tweet targeting Hopewell Chin’ono and Linda Tsungirirai Masarira. Previous tweets from the account have also criticized the same individuals targeted by embassy tweets, as well as other civil society actors.

At the time of writing, @cry_gurende had more than 4,700 followers. The account’s biography states, “Patriot par excellence. God fearing politician. Critic and hater of puppetry.” Notably, the Chinese embassy account uses strikingly similar metaphorical languages regarding “puppetry.” For example, a May 2022 tweet stated, “Renewed puppet show is coming! #Mr1K and their string-pullers are returning for another season of their poor show, to smear development-supporting Chinese investment & sow hatred between Chinese and Zimbabwean people.”

According to the 2019 Freedom on the Net report from Freedom House, “ZANU-PF is believed to pay progovernment commentators to defend the new administration and attack opponents on social media.” Freedom House noted that during the 2018 election, President Mnangagwa urged supporters to “dominate social media,” and that his call “coincided with an increase in anonymous accounts on both Facebook and Twitter that attacked perceived government opponents, especially human rights defenders and opposition party members.”

As evidenced in this case study, China’s media influence abroad can have outsized impacts in countries where freedoms are already limited. In the case of Zimbabwe, China provided political cover for ZANU-PF to crack down on journalists and civil society actors by spreading a narrative that claimed opposition figures were supported by foreign powers seeking to undermine the government.

The implications of China’s influence in Zimbabwe extend beyond the media environment. Chinese approaches to social media control are reported to have inspired Harare to develop a cybersecurity bill that grants the government broad authority in cracking down on speech online and detaining those who spread “harmful” information. Zimbabwe made its first arrests under the law in August 2022, in advance of the 2023 general election in which ZANU-PF aims to maintain its grip on power. The government charged arrested journalists under the provisions of the law regarding “spreading false data messages” on social media platforms.

When seeking to understand the implications of China’s involvement in media environments abroad, the domestic political conditions of the countries with which it engages are important. Countries show varying degrees of resilience in terms of the penetrability of their information environments to undue influence. In countries with a low level of existing resilience, the impacts on democratic prospects are perhaps the most severe.

Cite this case study:

Kenton Thibaut, “China spearheads social media campaign to attack civil society in Zimbabwe,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), November 9, 2022, https://medium.com/dfrlab/china-spearheads-social-media-campaign-to-attack-civil-society-in-zimbabwe-aaa0eecb475c.