How inauthentic Facebook accounts targeted detained Moroccan journalists

Facebook removed a network of user accounts with potential links to Morocco-based campaign de-platformed in 2021

How inauthentic Facebook accounts targeted detained Moroccan journalists

BANNER: Members of the Tunisian Journalists Union rally in support of imprisoned Moroccan journalists Omar Radi and Souleimane Raissouni on the occasion of World Press Freedom Day, May 3, 2021. (Source: Jdidi wassim/SOPA Images/Sipa USA via Reuters Connect)

As Moroccan authorities surveilled, harassed, and eventually imprisoned the journalists Omar Radi and Soulaimane Raissouni, an inauthentic and coordinated campaign on Facebook complemented this repression by posting salacious and derogatory content about the journalists. This network of forty-three Facebook accounts frequently amplified media outlets associated with Moroccan security services to denigrate the journalists and a range of Moroccan dissidents, some over a six-year period. It also amplified disinformation about Morocco’s use of Pegasus spyware and maligned Amnesty International’s investigation into its use. Radi and Raissouni are presently imprisoned on what the Committee to Protect Journalists has described as “trumped up sexual assault and ‘morals’ charges” that align with the government’s efforts to silence critical journalism and dissident voices in the country.

The DFRLab partnered with the University of British Columbia’s Global Reporting Centre and Simon Fraser University’s Disinformation Project to investigate the network as part of a larger project examining efforts to discredit and harass journalists globally. In response to our investigation, Facebook parent company Meta took down the forty-three accounts in May 2022.

The accounts uncovered during our investigation appeared to be working in a concerted effort on Facebook to share content aligned with Moroccan state aims. In addition to narratives targeting jailed Moroccan journalists Omar Radi and Soulaimane Raissouni, the accounts posted vigorous attacks on other human rights defenders and Moroccan citizens critical of the state. These include the jailed politician and lawyer Mohammed Ziane, the historian and human rights activist Maati Monjib, dissident and YouTuber Zakaria Moumni, and YouTuber Dounia Filali and her husband Adnane Filali.

Notably, Radi, Raissouni, and Ziane were arrested, charged, and imprisoned during the period in which the network was active. The earliest account in the network was active as of September 2016; other accounts were created as recently as April 2021, and were actively posting at the time Meta de-platformed the network.

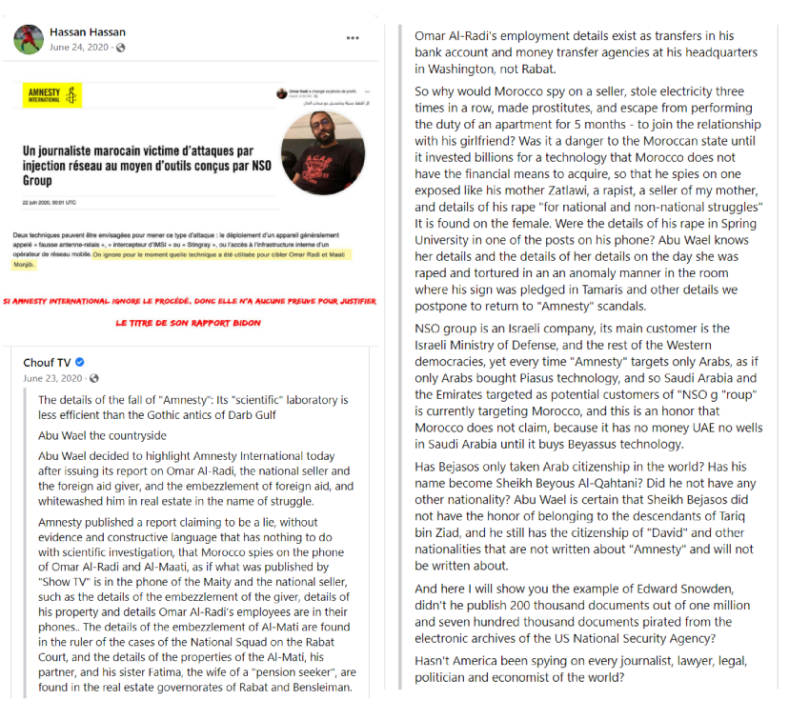

Many of the accounts shared the same content in close or identical timespans from a consistent set of Moroccan-state-aligned sources. The accounts also wrote derogatory comments about some of these journalists on Facebook posts of pro-government outlets. Some of the accounts liked each other’s identical posts, implying a degree of engagement coordination in addition to content coordination. Most of the their personal profiles largely consist of stock photos.

This is not the first time Meta has removed assets traced to Morocco. In February 2021, the company took down a network in response to an Amnesty International investigation. Meta’s description of the behavior of that network aligns with what we saw from the network of forty-three accounts that we identified. More notably, Meta removed the latest accounts as part of its ongoing efforts to prevent recidivism by networks previously de-platformed by the company, thus strongly suggesting the two networks were connected.

Given the repressive journalistic climate in the country, our investigation focused on analyzing social media behavior that engaged in coordinated harassment and appeared inauthentic. Part of the reason for this is because Meta considers coordinated inauthentic behavior grounds for de-platforming. Another motivation for focusing on this nexus is because it could imply that there is an entity — oftentimes state-linked — that is behind the harassment in a coordinated campaign, unlike instances of harassment originating from individual users.

Journalistic repression in Morocco

To understand the impact of this social media manipulation, it is critical to understand how the network of forty-three accounts we studied fits into Morocco’s broader repression campaigns against Radi and Raissouni. Both are journalists with a track record of independent reporting in a country which makes such coverage difficult. Both have also been targeted with spyware, along with other Moroccan journalists critical of the government.

A July 2022 Human Rights Watch (HRW) report described the manifold tactics that the Moroccan government — and entities directly or indirectly linked to it — use in repressing dissidents. These include unfair legal trials, physical and psychological intimidation, character assassination via salacious/sexual charges, harassment campaigns in state-aligned media outlets, targeting family members, and more.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, “[T]he Moroccan government has been using trumped up sex-related charges to prosecute and imprison journalists for their work.” These charges are designed to silence journalists and malign their characters. In the cases of Radi and Raissouni, these charges were preceded by surveillance, intimidation, and harassment campaigns in state-aligned media outlets that HRW described as pro-government media and the Intercept describes as the “defamation press” for their role in defaming activists and dissidents.

One of these outlets, Chouf TV, was the “highest-ranking domestic website in Morocco” in 2021, according to Alexa website analytics data documented by Freedom House. In its 2021 Freedom on the Net report, Freedom House noted Chouf TV’s reported ties with Moroccan security services and its history of publishing stories undermining the reputations of government critics:

Chouftv has gained a reputation for publishing reports that are largely driven by clickbait, and critics have questioned the outlet’s relationship with security forces given that it is almost always the first major media outlet to report from the scene of major news stories. For example, activists and journalists noted that Chouftv was the only outlet to report from the scene of the abrupt arrest in May 2020 of Moroccan journalist Soulaiman Raissouni. Activists and journalists believe…that Chouftv was tipped off by security forces….

In October 2020, Chouftv, a publication known for its close ties to the state, published intimate and private details about women’s rights activist Karima Nadir, including a copy of her underage son’s birth certificate. The same publication also shared surveillance footage of lawyer and former human rights minister, Mohamed Ziane, along with former police officer Ouahiba Khourchech. In addition to serving as Khourchech’s lawyer in her sexual harassment complaint against her boss, Ziane also represented journalist Taoufik Bouachrine and several activists with the Hirak movement.

As noted above, Chouf TV sometimes exhibits prior knowledge of planned actions by Moroccan security forces, including the conducting of arrests. As Pan-Arab independent outlet Raseef22 described it, “When ‘Chouf TV’ begins publishing articles about a certain person, this is a sign that the worst awaits them, and that those in control of matters now have made the decision to punish them and take revenge on them, the examples of this being manifold and repeated.”

This situation arose regarding Raissouni’s arrest. As noted by The Intercept, Chouf TV published an ominous story about Raissouni five days prior to his arrest, suggesting that he would be in trouble by the start of that year’s Eid al-Fitr celebrations, which were set to begin on May 23, 2020. Law enforcement arrested him on May 22, two days after he published an editorial critical of Moroccan authorities. Meanwhile, prosecutors also cited two Chouf TV articles from June 14 and June 21, 2020 in its investigation of Omar Radi.

Given Chouf TV’s attacks on Radi and Raissouni, as well as its reported links to security services, it seems particularly significant that the network of Facebook accounts identified during our investigation repeatedly amplified Chouf TV coverage about the two journalists. Our research uncovered a social media component to the “methodology to muzzle dissent” previously outlined by Human Rights Watch. The forty-three accounts repeatedly amplified Chouf TV coverage about Radi and Raissouni before, during, and after their prison sentences. Many posted derogatory comments about Radi and Rassouni on posts from Chouf TV and other outlets, giving the appearance that there were real people on Facebook who were condemning them.

Comments on Facebook posts harassed journalists

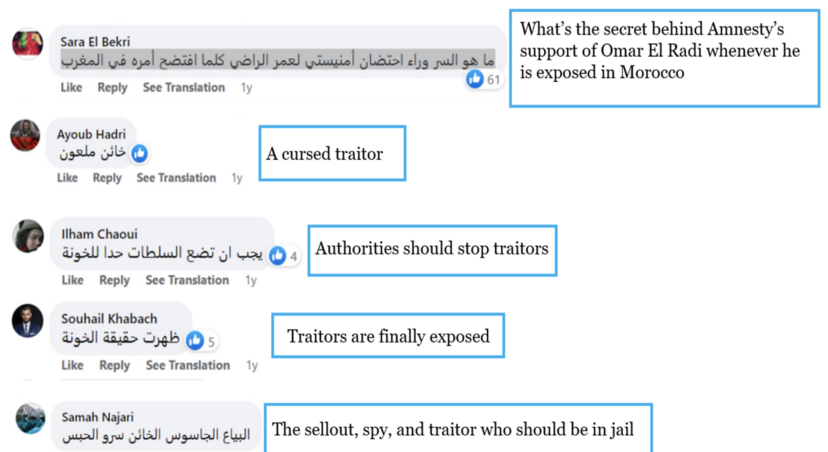

The inauthentic network routinely commented on Facebook posts from Chouf TV and the news outlet Barlamane. Many of these comments denigrated journalists, while others glorified the Moroccan state apparatus. These comments frequently received numerous likes from other accounts.

An example of this is a June 1, 2020 Chouf TV post harassing Raissouni and a family member, Youssef Raissouni, the secretary general of the Moroccan Association of Human Rights. This post occurred after authorities arrested Soulaimane Raissouni in May 2020, but prior to his sentencing on July 9 of that year. The post amplified claims of disgraceful actions by the Raissounis that resulted in them allegedly abandoning a child. Twelve of the forty-three accounts we identified posted comments, the majority of which maligned the Raissouni family. Additional members of the extended Raissouni family have been harassed by the state, including Soulaimane’s niece, Hajar Raissouni, who was surveilled and jailed for an alleged illegal abortion before receiving a pardon after public outcry. One of the comments garnered thirty-five likes for writing, “The Raissouni family is surrounded by sex and repression, a family of scandals and crimes.” Another comment asked for the harshest sentence possible for Soulaimane Raissouni, stating, “The offender must be punished with maximum penalties for committing a major sin.”

In another example, a July 2, 2020 Chouf TV post denigrated Omar Radi by calling him a spy and alleged that Amnesty International had tried to cover up Radi’s espionage. Notably, this post was published exactly one week after authorities summoned Radi on possible espionage charges, prior to his arrest later that month. The Chouf TV post also attacked other dissidents by comparing them to Radi. Five of the Facebook accounts left negative comments on the post. Most of these comments called Radi a traitor; one said that “authorities should stop traitors” while another remarked that he should be in jail. Another comment questioning Amnesty International’s support of Radi received sixty-one likes.

Certain individual accounts within the network appeared to be prolific commenters. One account, “Sara El Bekri,” commented on at least thirteen posts from Chouf TV and Barlamane. Approximately half of their comments denigrated Moroccan journalists and dissidents, while the other half included a smattering of posts praising the Moroccan king, state police, and army. One comment attacked Turkey, accusing the country of supporting terrorism.

A fake profile named “Youssef Slimani” commented on three different posts by Chouf TV and Barlamane that attacked Omar Radi and Soulaimane Raissouni. The first comment directed towards Raissouni exclaimed, “Very shameful,” while another comment discussed his alleged corruption and the need to punish him: “A greedy association. Riassouni is a symbol of corruption and should be punished to make an example out of him.” A third comment praised Chouf TV for exposing Omar Radi, stating, “Good job Abu Wael, you exposed them.” The name Abu Wael is a reference to Chouf TV writer Abu Wael al-Rifi, whose articles routinely targeted Radi and Raissouni; according to Human Rights Watch, Abu Wael al-Rifi is reportedly a pseudonym used by Driss Chahtane, the director of Chouf TV.

Harassing content

Many of the fake accounts coordinated sharing content about Moroccan journalists and dissidents. This content was often salacious and biased.

In one example, at least thirteen fake accounts shared a post linking to a February 7, 2022 MarocMedias article about Raissouni’s conviction appeal. The article claimed that Raissouni’s lawyer indirectly acknowledged Raissouni’s guilt during the original trial. After finding him guilty, the court had sentenced Raissouni on July 9, 2020 to five years imprisonment for sexual assault. During his appeal, prosecutors sought to expand his sentence to ten years. On February 23, 2022, the appeals court upheld Raissouni’s original five-year sentence.

The accounts shared the February 7 MarocMedias article in quick succession, most of them on the following day. Eleven of these posts occurred in the same forty-five-minute timespan on February 8, with three of them occurring within the same minute at 12:07am local time. In addition to coordinating the timing of their comments, some of the fake accounts liked each other’s posts.

Several of the other fake accounts shared the MarocMedias article from other pages which had also posted it, including from the pages السلاويين الرجـــــــــــــولة +18 (“Machismo Slaouiyine 18+”) and الدكالية doukkalia (“doukkalia vault”). At least six of the accounts in the network shared the same post from the page سلا مدينة الإجـــــــــــــرام +18 (“Sale, The City of Crime 18+”). The post discussed Omar Radi and journalist Hafsa Boutahar, who had accused Radi of sexually assaulting her, quoting Boutahar as saying, “I wish international organizations supported me the same way they support separatist Moroccans.” The post included a MarocMedias article featuring an interview with Boutahar after an appeals court upheld Radi’s six-year sentence on March 3, 2022. All six accounts’ Facebook shares occurred on March 5 and March 6, just days after the appeals court ruling.

In another example, at least thirteen of the fake accounts shared a post from the Facebook page المغربي الصديق (“The Friendly Moroccan”) that denigrated Zakaria Moumni, a former kickboxer and current YouTube influencer previously imprisoned for eighteen months in Morocco for criticizing the government. “And now, the bombshell that everyone is waiting for…the scandal of the enemy of the homeland Zakaria Momni and the truth of his suspicious marriage…what’s coming next is shocking,” the post stated, promoting the release of another video spreading rumors about Moumni.

Many of the posts were published within a roughly two-hour timeframe on February 8, 2022. The first of these shares occurred at 10:42pm local time, twenty-one minutes after the Facebook page post initially appeared. Other accounts in the network shared the same post when it was amplified elsewhere on Facebook.

In addition to the fake accounts posting the same content at similar times, there were other seemingly coordinated behaviors that were noteworthy. On March 4, 2022, there were at least five instances in which three accounts in the network shared the same posts, sometimes within one minute of each other. The posts included links from Moroccan outlets like Kafapresse, Cawalisse, and al3omk.com.

The accounts also shared content harassing Moroccan dissidents, particularly several YouTubers. Amnesty International previously reported that the Moroccan government targets dissident YouTubers in the country. Some content focused on Dounia and Adnane Filali, a Moroccan couple now living abroad who face charges in Morocco. Dounia Filali’s YouTube channel, which currently has more than 300,000 subscribers, has criticized the Moroccan regime. The fake accounts also targeted YouTuber Zakaria Moumni.

Disinformation about Morocco’s use of Pegasus spyware

The network of fake accounts also spread disinformation about Morocco’s use of Pegasus surveillance technology supplied by the NSO Group. More broadly, it questioned the veracity of the Pegasus Project, an investigation by Forbidden Stories and Amnesty International into the surveillance of journalists around the world by various government clients of the NSO Group. Notably, the investigation detected Pegasus spyware on Omar Radi’s phone, while Soulaimane Raissouni appeared on a list of Pegasus surveillance targets.

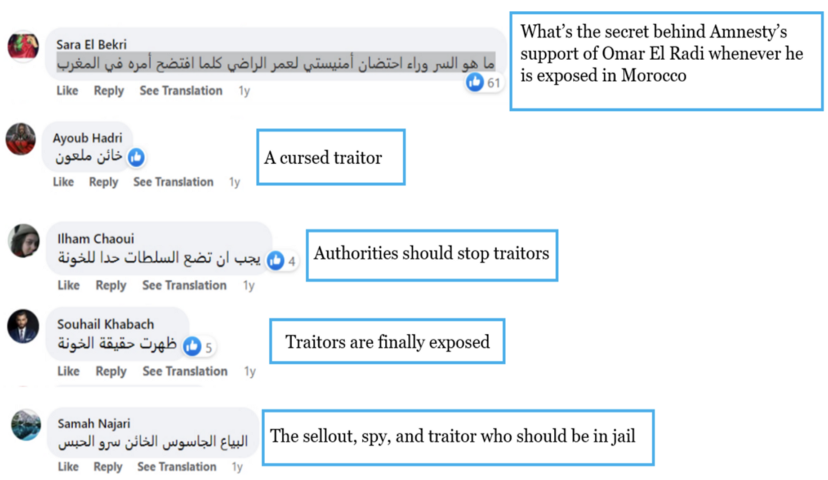

The accounts specifically mentioned Amnesty International, Omar Radi, and French courts in posts amplifying state-aligned outlets Chouf TV, Kafapress, and Kifache, among others. Some of these posts attempted to refute the Pegasus Project through distortion and spin. One such post on June 23, 2020 included the full text of a Chouf TV article from earlier that day spreading disinformation about Omar Radi and an Amnesty International report about Morocco surveilling him. The timing was significant — according to the Intercept, the Moroccan prosecutor’s office sent a letter to police that same day asking them to investigate Radi because of two other Chouf TV articles about him. Authorities summoned Radi on potential espionage charges two days later.

As previously mentioned, the Chouf TV Facebook post and accompanying article targeted an Amnesty International report published the previous day, which described how the Moroccan government surveilled Omar Radi with NSO spyware. Chouf TV falsely claimed that the Amnesty report failed to supply sufficient evidence that Morocco had surveilled Radi. It also accused Amnesty of targeting Arab countries instead of exposing surveillance by Western countries, and accused Amnesty of allegedly protecting Western spies.

Meanwhile, on March 25, several accounts posted a Kifache article within an hour of each other, while others amplified an article from Kafapress. That same day, a French court threw out a defamation lawsuit filed by the Moroccan government. Morocco’s Paris embassy had filed the lawsuit to dispute the fact that Morocco used the NSO Group to engage in surveillance, accusing Forbidden Stories, Amnesty and other entities of defamation. Both Kifache and Kafapress criticized the French courts, praised the Moroccan government, and claimed the report was part of a campaign to undermine Morocco. The Kifache article even implied that the French court engaged in tactics similar to Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels, and paraphrased an quote often attributed to him: “If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it.”

Additionally, some of the fake accounts shared posts from the Moroccan Association for the Rights of Victims (Association Marocaine des Droits des Victimes, or AMDV), a recently-created organization representing Omar Radi’s alleged victim. Some of the AMDV posts they amplified originated from Moroccan-state-aligned outlets, including Express-Temara and Aabbir. These posts shared a statement from AMDV about the case of Soulaimane Raissouni, in which they opposed attempts by Raissouni’s wife and his niece Hajar Raissouni to prove his innocence. Other posts quoted Raissouni’s alleged victim. The timing of these posts aligned with Raissouni’s sentencing appeal from February 7 to February 23, 2022, as well as the days immediately following it.

Many of the forty-three fake accounts were active for several years. Based on a review of when they first uploaded profile pictures — a useful proxy for a Facebook account’s initial launch date — the oldest two accounts appeared by September 2016, while the newest account appeared no later than April 2021. Some of the accounts were also “friends” with each other and liked each other’s pictures, including profile pictures. The profile pictures were typically stock photos, easily identifiable through a Google reverse-image search.

Connections to previously identified Moroccan network

Meta removed the forty-three accounts in May 2022 after determining they were linked to a previous network of 385 accounts, six pages, and forty Instagram accounts de-platformed in February 2021. The latter network was first reported by Amnesty International, and Meta determined that it “originated primarily in Morocco and targeted domestic audiences.”

When announcing the original takedown in February 2021, a Meta report stated:

The people behind this network used fake accounts — some of which had already been detected and disabled by our automated systems — to post in multiple Groups at once to make their content appear more popular than it was. They also frequently used these accounts to comment on news and pro-government stories from various news outlets including Chouf TV.

The people behind this activity posted memes and other content primarily in Arabic and French about news and current events in Morocco including praise for the government’s response to the coronavirus pandemic, its diplomatic initiatives, Moroccan security forces, King Mohammed VI and the director of the General Directorate for Territorial Surveillance. They also frequently posted criticism of King’s opposition, human rights organizations and dissidents.

Meta’s assessment of the network they de-platformed in February 2021 aligns with our observations regarding the forty-three accounts we investigated in 2022. The forty-three accounts engaged in disinformation and character assassination to attack journalists in Morocco. These behaviors include amplifying posts and articles denigrating Omar Radi and Soulaimane Raissouni, and posting harassing comments on media outlets’ Facebook posts. The network was active for at least six years; during that time frame, the Moroccan government arrested and imprisoned several of the individuals targeted by the accounts.

It also seems particularly significant that the network was active on notable dates when Radi and Raissouni were threatened with arrest or in court, including prior to their initial sentencing and during their appeals. This leads us to conclude that this social media manipulation was among an array of tools leveraged as part of a much broader campaign of state-aligned harassment and intimidation.

Alyssa Kann is a Research Associate with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Abde Amr is a Research Assistant with the Disinformation Project at Simon Fraser University.

Chris Tenove is a Research Associate at the Global Reporting Centre and Assistant Director of the Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions, University of British Columbia.

Ahmed Al-Rawi is an Associate Professor at the School of Communication at Simon Fraser University, Canada and is the Director of the Disinformation Project.

This case study was published in partnership with the Global Reporting Centre and Simon Fraser University’s Disinformation Project. The research is part of a larger Global Reporting Centre project examining efforts to discredit and harass journalists globally.

Cite this case study:

Alyssa Kann, Abde Amr, Chris Tenove and Ahmed Al-Rawi, “How inauthentic Facebook accounts targeted detained Moroccan journalists,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), November 17, 2022, https://medium.com/dfrlab/how-inauthentic-facebook-accounts-targeted-detained-moroccan-journalists-fef53534bada.