Anti-LGBTQ+ campaigns spread on Arabic social media

The World Cup fueled online and offline campaigns promoting anti-LGBTQ sentiment and hateful rhetoric

Anti-LGBTQ+ campaigns spread on Arabic social media

Share this story

THE FOCUS

BANNER: Photo of a mural of Sarah Hegazi in Amman, which has now been painted over. (Source: Raya Sharbain/Wikimedia Commons)

Around the 2022 men’s soccer World Cup in Qatar, the DFRLab identified Arabic anti-LGBTQ+ campaigns on Facebook and Twitter and traced them to Qatar, Algeria, Egypt, Kuwait, Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia.

The 2022 World Cup instigated a notable rise in anti-LGBTQ+ campaigns led by both state and non-state actors in the Arab world. The World Cup, which concluded in December 2022, drew international attention to the mistreatment of LGBTQ+ people and repressive legislation in the host country, and other countries in the region, where same-sex relations are illegal and punishable by law. While anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment is not new in the region, the international spotlight on the rights of LGBTQ+ people drew a backlash in the Arab world, which resulted in the rise and popularity of online anti-LGBTQ+ campaigns.

Government-led attacks and crackdowns on LGBTQ+ people in the region have increased in recent years. Governments deploy repressive legislation purportedly aimed at protecting social values, customs, and morality to instead punish members of the LGBTQ+ community. Qatar’s security forces arbitrarily arrest, abuse, and mistreat LGBTQ+ individuals, with documented cases of transgender women being forced to attend conversion therapy sessions. In Egypt, where homosexuality is criminalized in the penal code under the provision for combating adultery and debauchery, Egyptian police digitally harass LGBTQ+ people on dating and social media apps and utilize the evidence to arrest and detain them. The use of social media and dating apps to entrap people has also been recorded in Iraq, Jordan, Tunisia, and Lebanon. In addition, the Lebanese LGBTQ+ rights and protection organization Helem documented 1,262 LGBTQ+ rights violations in 2021 alone, impacting Lebanese citizens and Syrian refugees, 369 of which pertain to arrests, blackmail, physical violence, rape, and sex trafficking.

Anti-LGBTQ+ government crackdowns feed negative sentiment among the public about LGBTQ+ people and encourage hateful conduct. Several of the anti-LGBTQ+ campaigns identified by the DFRLab were led by civil society groups and individuals who promote negative attitudes against LGBTQ+ people and encourage others to share similar content on social media. Such campaigns center their message around the rejection of homosexuality in their societies, claiming it does not belong within their faith and morals. A survey conducted by five organizations in 2020, which gathered responses from 450 LGBTQ+ Arabic speakers and community supporters, revealed a large volume of hate speech and threats targeting LGBTQ+ people, impacting their physical safety and mental health. Anti-LGBTQ+ campaigns have also taken advantage of Twitter’s decline in content moderation since Elon Musk became chief executive officer, when hate speech and abusive speech – generally and specifically against LGBTQ+ people and organizations – began once again to become more prevalent.

Government-led campaigns

The DFRLab identified four government-led campaigns – in Algeria, Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia – to ban LGBTQ-related slogans or symbols. Two campaigns launched in June 2022, possibly motivated by International Pride Month. In a Twitter video posted on June 14, 2022, the Saudi Ministry of Commerce announced that it would seize and confiscate products that include symbols and indications of homosexuality or that “contradict normal instinct.” At the time of writing, the video had more than 150,000 views on Twitter. The ministry announced that statutory penalties would be imposed on establishments that violated the order. Another tweet, published two days later, said the ministry “continues to seize all products and commodities that violate the teachings of our true Islamic religion, our traditions, customs, and culture” and explained how residents could report violations.

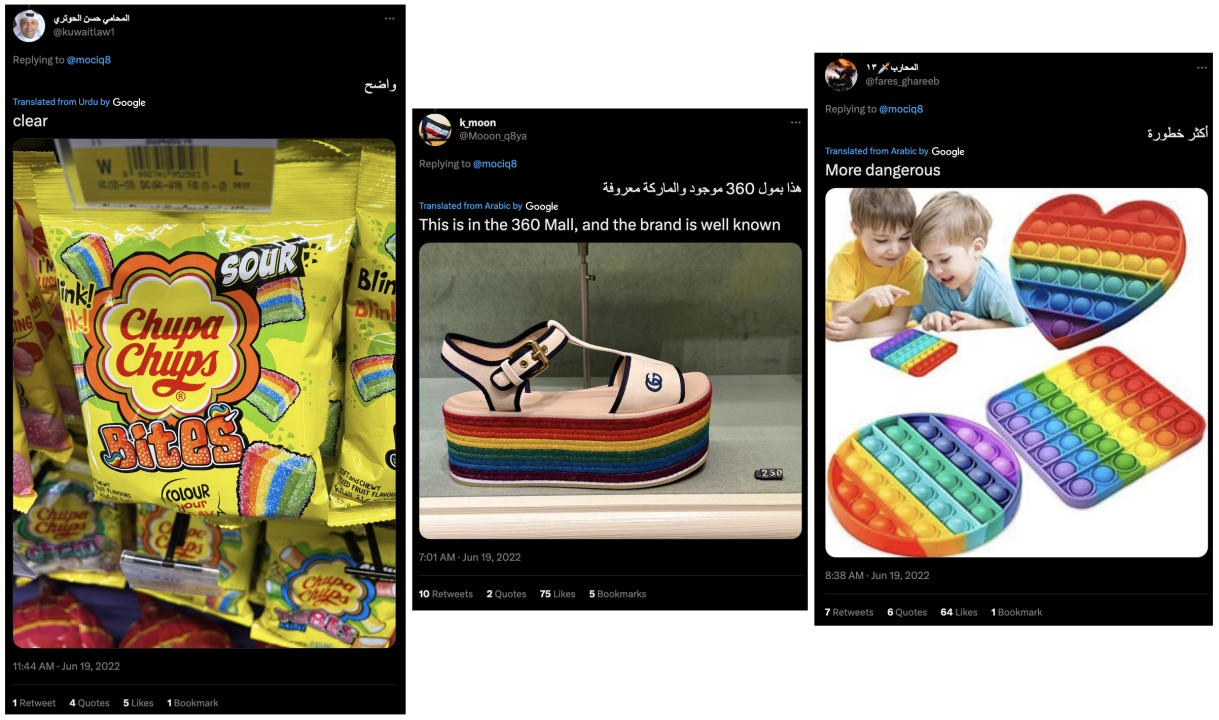

The Ministry of Commerce and Industry in Kuwait issued a similar announcement on June 19, 2022, encouraging citizens to report pride flags or other slogans that “violate public morals,” implying that the pride flag is contrary to public morals. The announcement utilized the hashtag #شارك_في_الرقابة (“participate in oversight”), which is regularly used in ministry announcements. The tweet had more than 26,000 likes and 12,000 retweets at the time of writing.

Most of the comments applauded the measure, with some commenters sharing a variety of violating products, including clothing items, candy, and children’s toys.

The Algerian Ministry of Trade and Export Promotion followed suit in December 2022, announcing a national awareness campaign from January 3 to 9, 2023. The ministry’s announcement warned about the “risks and negative consequences” of selling products bearing any resemblance to the pride flag. As part of the campaign, the government circulated announcements to citizens via text messages, television, radio, and media publications, with the slogan “protect your family, beware of products that carry colors and symbols contrary to faith and our moral values.” In several provinces, officials organized events in schools and cultural centers to distribute flyers and discuss the campaign with community members. On its Facebook page in January 2023, the ministry posted a video featuring media coverage and a press conference regarding the seizure of 38,542 children’s toys and school supplies, as well as 4,561 colored copies of the Quran.

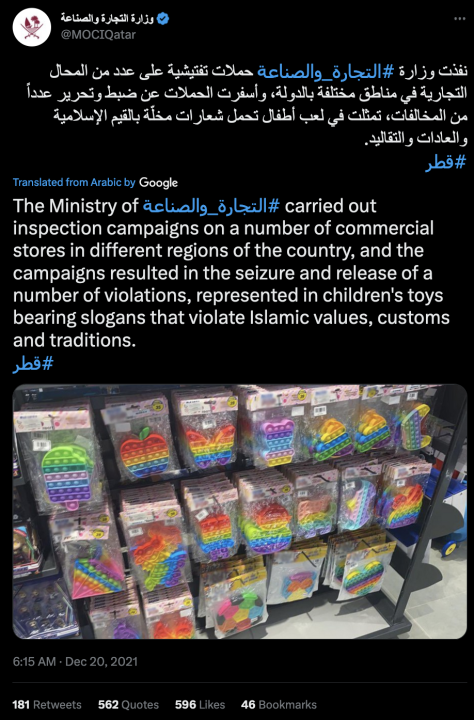

One year before Qatar hosted the World Cup, the Qatari Ministry of Commerce and Industry conducted an inspection campaign on retail shops in December 2021 and seized products for “bearing slogans that violate Islamic values, customs, and traditions.”

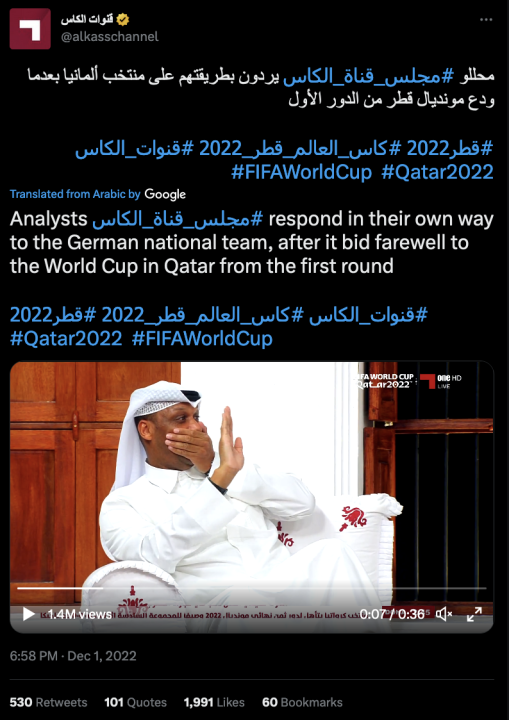

During the World Cup, the pride flag and other symbols gained further attention when Qatari stadiums refused entry to individuals wearing rainbow-colored clothing items. As a result, several European teams decided not to wear the rainbow-branded OneLove armband, a symbol of inclusion, to avoid being penalized by the International Federation of Football Associations (FIFA). Germany’s team was heavily criticized online for covering their mouths with their hands in a pregame photo, a form of protest against the censorship of LGBTQ-related materials.

Qatari sports channel Alkass subsequently aired a segment where a panel mocked Germany’s protest after its elimination from the tournament.

In Lebanon, the first country in the region to celebrate pride and where LGBTQ-friendly spaces and events take place in the capital Beirut, authorities have also attempted to crack down on the community. The Minister of Interior issued a letter in June 2022 banning LGBTQ+ gatherings. The ban was temporarily suspended in November after Lebanese advocacy organizations Helem and Legal Agenda filed a lawsuit with the State Council in August. However, the Minister of Interior continued instructing law enforcement to ban LGBTQ+ gatherings as the State Council formulated its final ruling.

Symbols associated with LGBTQ+ people, such as the pride flag, have gained increased attention in the region in recent years. In 2017, Egyptian authorities imprisoned LGBTQ+ activist Sarah Hegazi after she raised a pride flag in Cairo at a concert of the Lebanese indie band Mashrou’ Leila. Hegazi took her own life in 2020 after suffering from depression and loneliness in Canada, where she had sought asylum after being tortured in Egypt. The band, whose lead singer identifies as queer, received death threats and eventually disbanded following targeted online harassment and the banning of the group’s concerts in Lebanon and other countries.

Civil society-led campaigns

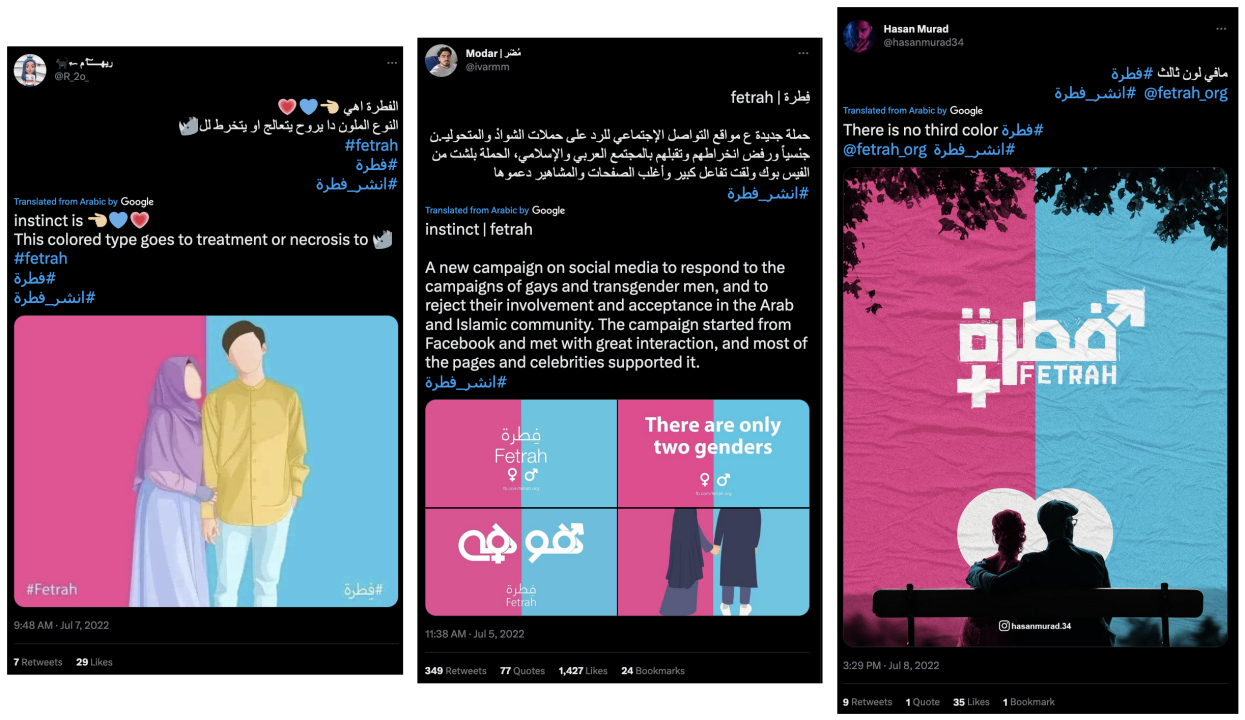

An online campaign called Fetrah (“human instinct”) emerged on Facebook in Egypt in June 2022; the campaign used a distinct blue and pink flag and the slogan “there are only two genders.”

Designed by three Egyptian marketing professionals, the campaign encouraged the rejection of homosexuality and called on online audiences to voice their support for this message. After gaining popularity among audiences in Egypt and Morocco, Meta removed Fetrah’s official Facebook and Instagram accounts in July. Fetrah campaigners posted on their Telegram channel about the closure of the Facebook account, which had two million followers. The Telegram post stated, “as is the custom of the West in restricting freedoms, if the opinion is contrary to their whims, they close the page, but they will not be able to finish the idea because it is in the minds now. The power of the idea terrifies them…the power of Fetrah terrifies them….” The post also included a link to an alternative Facebook page, accessed with the URL suffix “Fetrah.backup,” that is now unavailable. Fetrah’s Telegram channel has more than 13,000 subscribers but has not posted since July 8, 2022. On July 9, Fetrah tweeted that Facebook removed all of its alternative pages.

Twitter also suspended Fetrah’s account in mid-July, after it attracted more than 70,000 followers. The page remains suspended today, despite the reinstatement of many previously suspended accounts following Elon Musk’s takeover.

When Fetrah’s social media accounts were active, the campaign primarily posted its blue and pink logo with the slogan “there are only two genders” and the hashtag #انشر_فطرة (“post fetrah”), which encourages other users to spread the message. Some supporters tweeted messages that can be categorized as hate speech as they suggest that LGBTQ+ people should be “treated or neutered” and excluded from Islamic and Arab societies.

Several alternative pages and groups have surfaced on Facebook to continue supporting the campaign. The DFRLab investigated four groups and two pages branded with the Fetrah campaign name and flag. The assets were all created or renamed in early July 2022. Between July 1 and July 10, 2022, at least six Facebook groups or pages either launched under the name or changed their names to “Fetrah.”

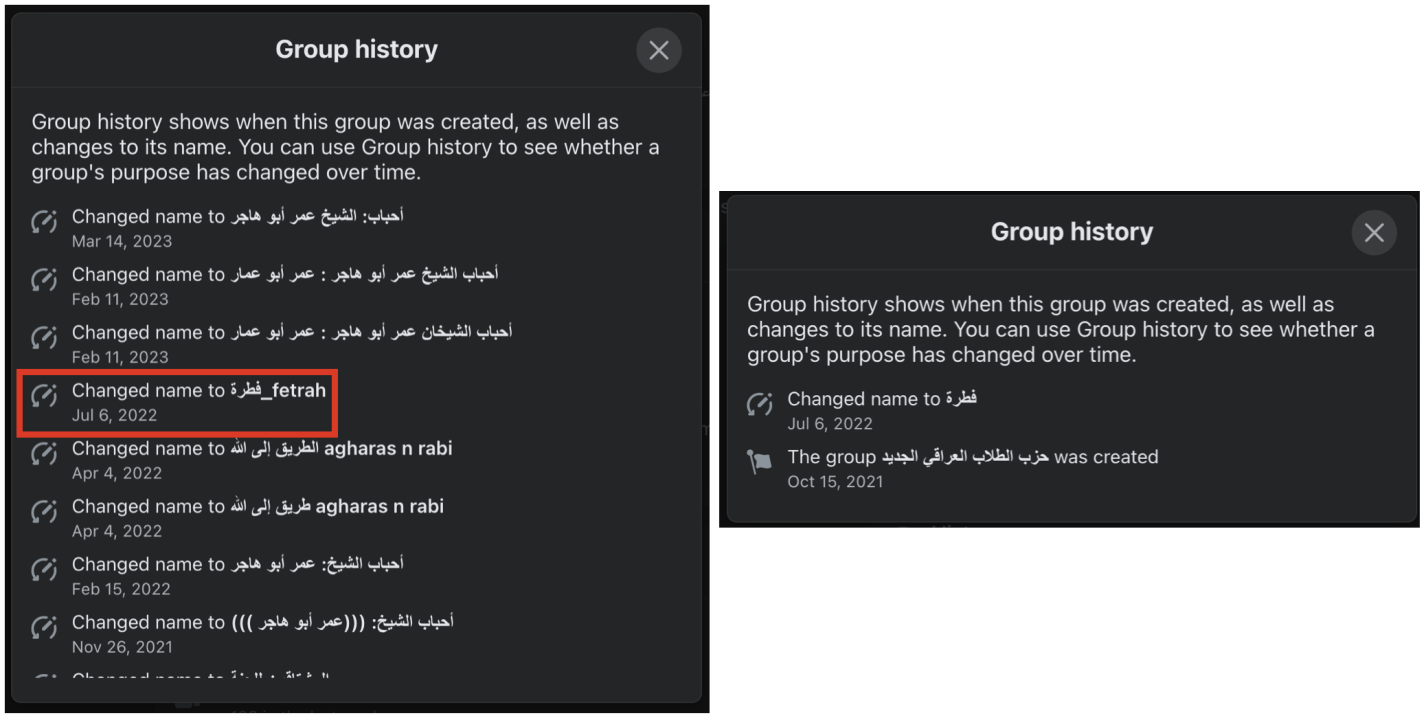

One of the identified groups (فطرة_fetrah) has more than 90,000 followers and posts primarily religious content, such as verses from the Quran, and its location is set as Morocco. The group was created on May 9, 2020, and has changed its name several times since its inception, including the stint from July 6, 2022, to February 11, 2023, when it went by فطرة_fetrah. The group’s first name was “عصام الصاقي -issam essaqui,” and its name changes often reference a specific religious figure or Sheikh. This suggests that the operators repurposed the religious group to support the anti-LGBTQ+ campaign in the months before and after the World Cup.

Another group (فطرة) was created on October 15, 2021, with the name حزب الطلاب العراقي الجديد (“New Iraqi student party”). It also changed its name to Fetrah on July 6, 2022, and remained named Fetrah at the time of writing. A recent post in the فطرة group contained a QR code linking to an article with information about the Prophet Lot verses from the Quran, which warn about the supposed dangers of homosexuality, and the Fetrah campaign message and slogan “there are only two genders.” One narrative shared in the group quotes the work of Nobel prize-winning German biologist Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard, who gave an interview in August 2022 stating that biologically there are only two sexes and stressing the need for a distinction between biological sex and gender. Nüsslein-Volhard’s words have been used by various anti-trans groups. Posts to فطرة include this content despite its administrator stating that “bullying of any kind isn’t allowed, and degrading comments about things like race, religion, culture, sexual orientation, gender or identity will not be tolerated.” Prior to the name change, the group had not posted religious content and had primarily posted about student exams, video games, and Iraqi news.

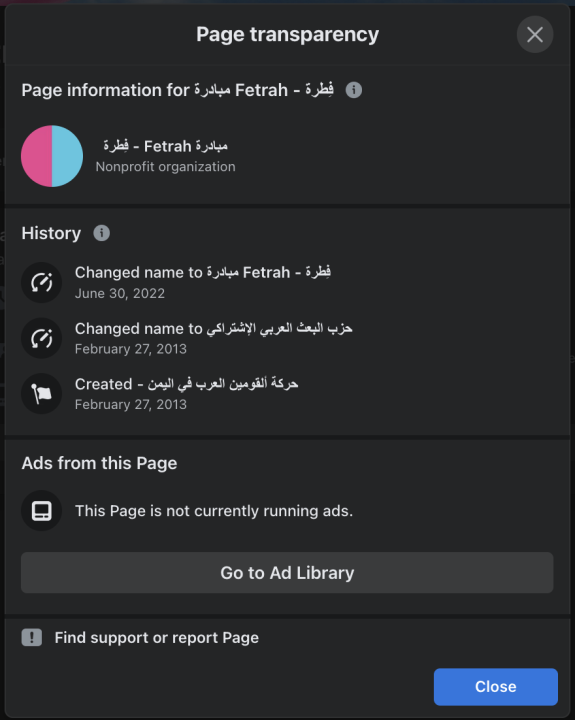

The oldest asset the DFRLab examined was a Facebook page created on February 27, 2013. The page was first named حركة ألقومين العرب في اليمن (“Arab nationalist movement in Yemen”) but changed its name to حزب البعث العربي الإشتراكي (“Arab Socialist Baath Party”) on the same day. Between February 2013 and July 2022, the page retained the same name; on June 30, 2022, however, it was renamed مبادرة Fetrah – فِطرة.

The page had only made two posts prior to changing its name in 2022. After the name change, the page began posting frequently. The page shared various posts from Fetrah supporters, including several Facebook pages that identify as businesses. Notably, several Egyptian footwear stores, one with more than one million likes and followers, supported the campaign (here, here, here, and here). The campaign was also amplified by soccer fan pages, some with more than one million likes and follows (here, here, here, and here). In addition, Cairo’s Triple F youth sports club posted in support of the Fetrah campaign with the caption, “Because we believe that our role is not just training, but contributing to the preparation of a new generation, we were the first sports academy in Egypt to support the Fetrah campaign.”

A Facebook page called Fetrah – فِطرة was created on July 9, 2022, and now has 70,000 followers. Three page administrators are located in Egypt and one is in Saudi Arabia. During the World Cup, the page posted pictures and a video of soccer match attendees holding Fetrah posters inside the stadium. The page also posts information that aligns with the campaign message, such as a post about US clinical psychologist Joseph Nicolosi’s views on homosexuality in males being related to childhood trauma. Nicolosi’s website claims that he assists “clients with their goal to reduce their same-sex attractions and explore their heterosexual potential” and that homosexuality “is an adaptation to trauma.”

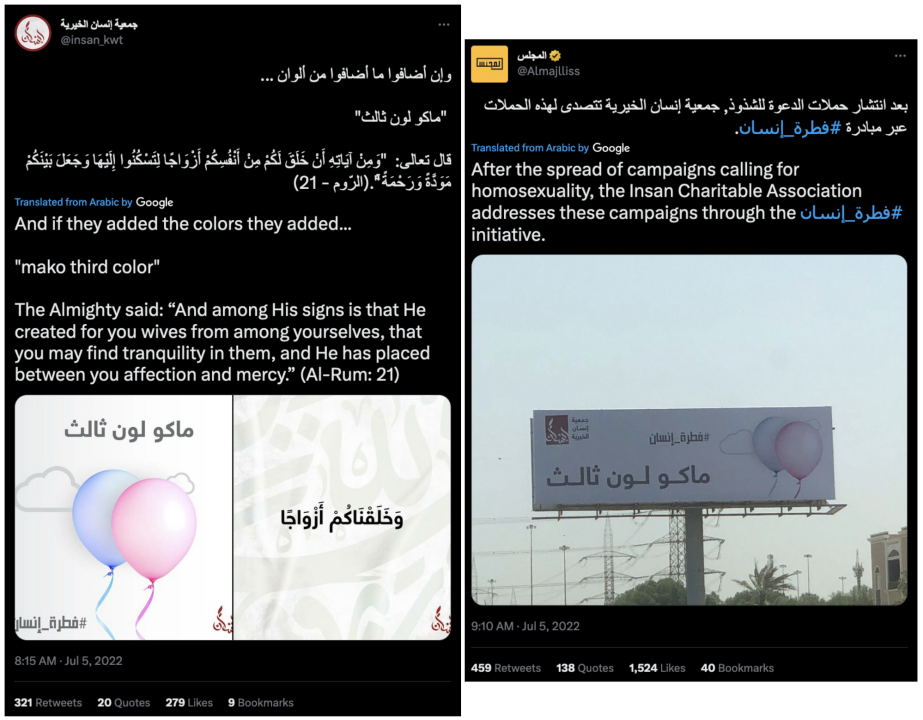

In Kuwait, the organization Insan launched a similar campaign on July 7, 2022, with the slogan “No Third Color” and a logo showing two balloons with blue and pink colors. Insan socialized the campaign on Twitter with several posts that included Quranic verses and used the hashtag #فطرة_إنسان ( human instinct). In addition, a street billboard appeared in Kuwait bearing the hashtag and logo.

Another campaign led by more than twenty-five civil society organizations in Kuwait kicked off in December 2022 with online posters stating, “He’s not like me, I’m a man, and he is gay” or “She is not like me, I’m a woman, and she is a lesbian.” Billboards promoting the online posters were seen in Kuwait during the same week.

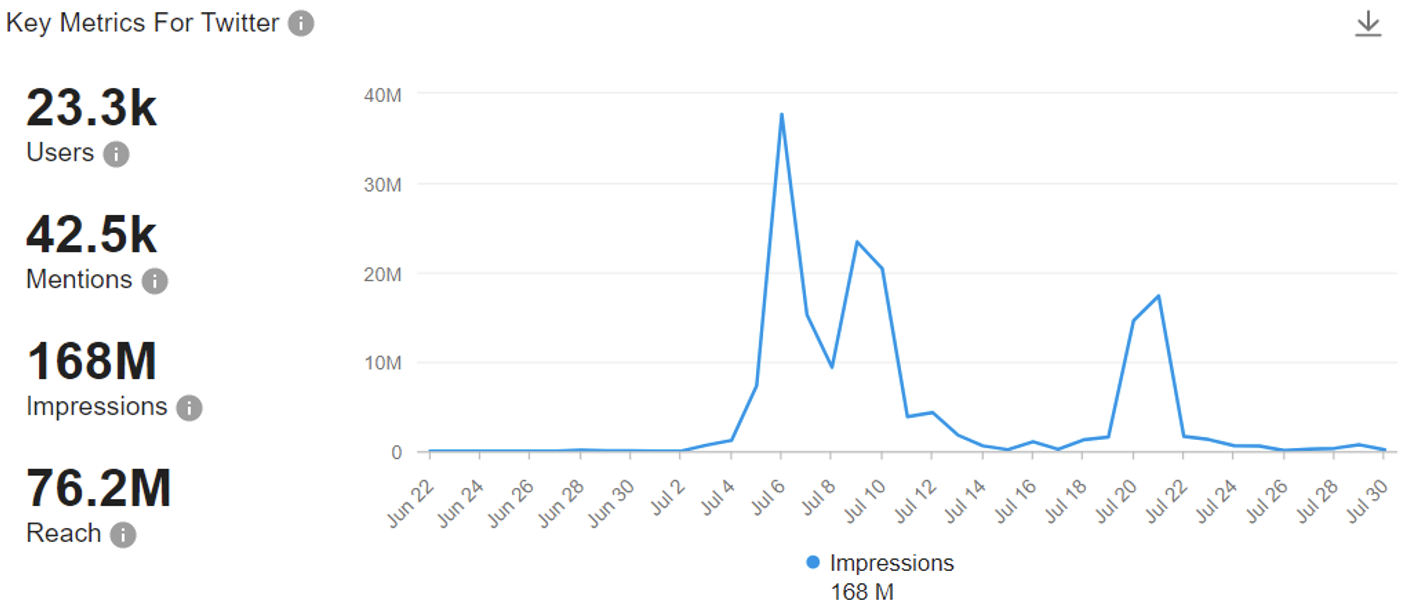

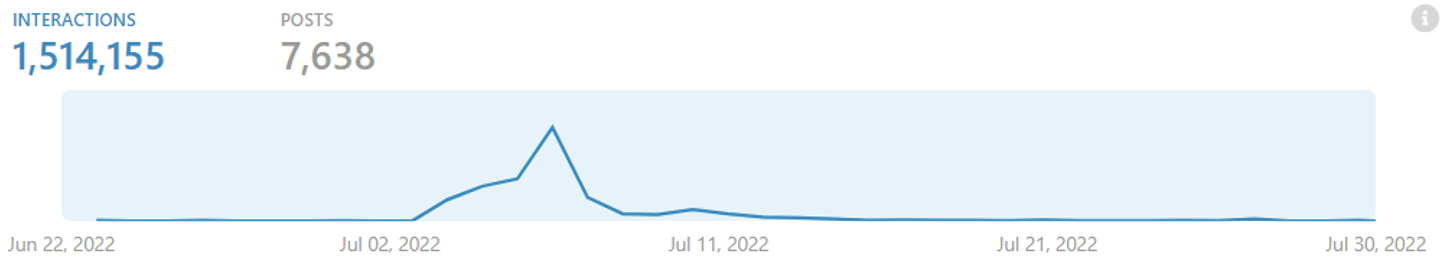

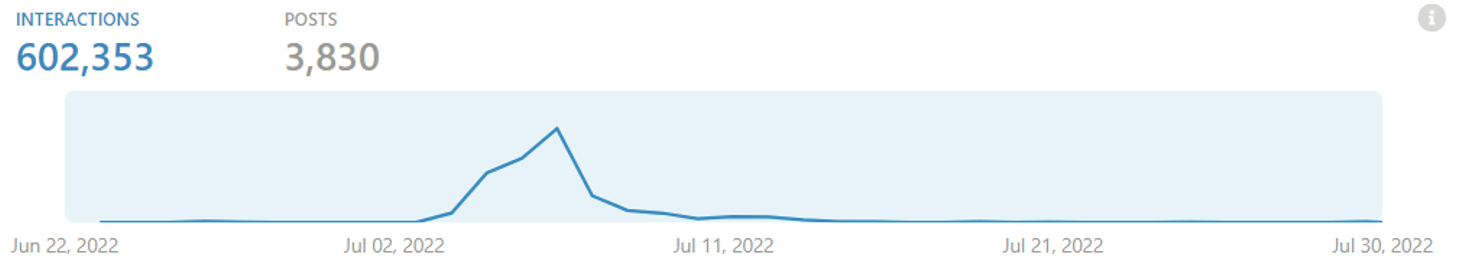

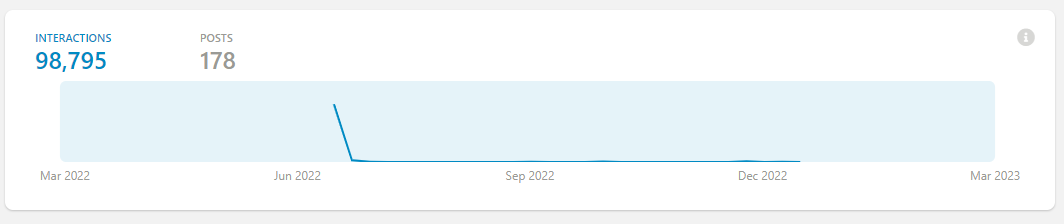

The DFRLab analyzed audience engagement with these campaigns by monitoring interactions with the campaigns’ relevant slogans, posters, hashtags, and comments. The campaign in Kuwait did not generate much interaction beyond a few users reposting pictures of the publicly posted posters and billboards. The Fetrah campaign, however, attracted thousands of users across the region. The DFRLab used Meltwater Explore and CrowdTangle to analyze the reach of the campaigns and their influence among online users. The Fetrah campaign kicked off in June 2022 and peaked in popularity during the first two weeks of July. The campaign’s popularity started to dwindle with the closure of its social media accounts on Facebook and Twitter in mid-July.

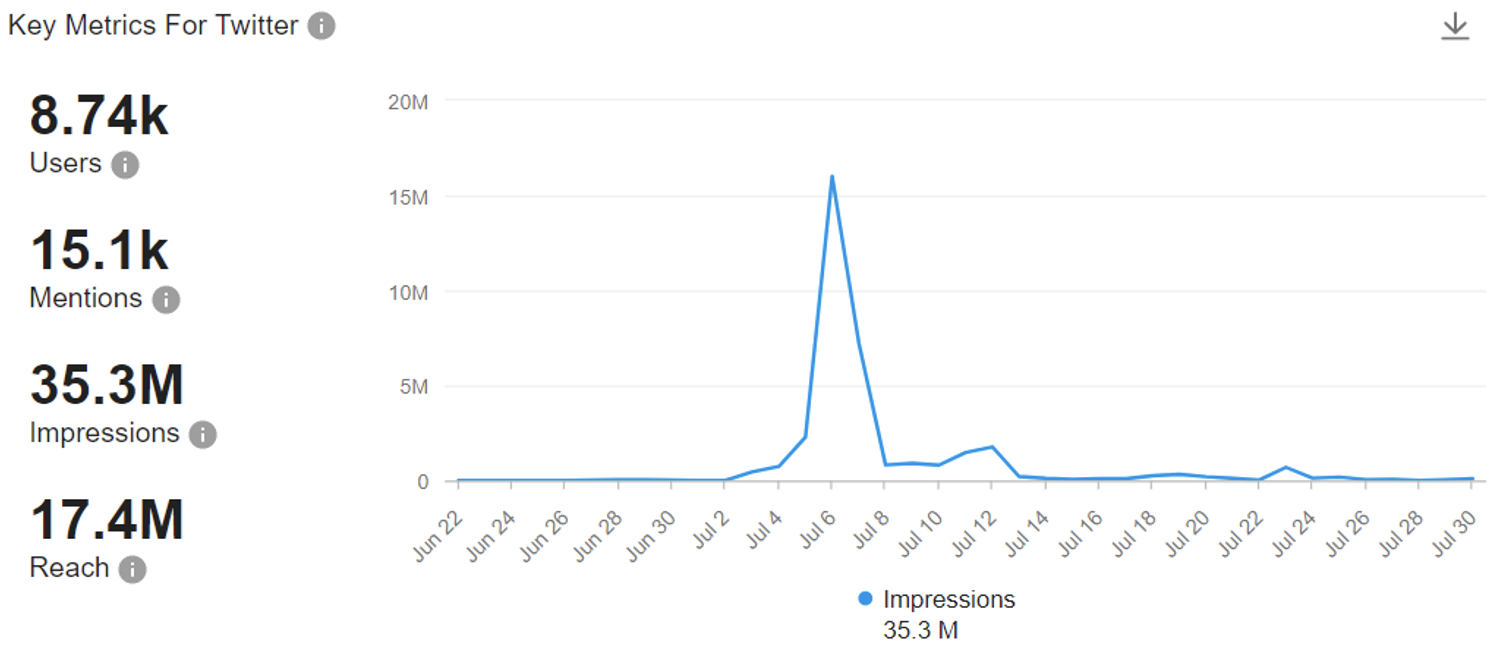

Between June 22 and July 30, the hashtag #فطرة (Fetrah) was mentioned 42,526 times by 23,337 unique Twitter user accounts.

Meanwhile, the English-language hashtag #Fetrah was mentioned 15,131 times by 8,741 unique Twitter user accounts.

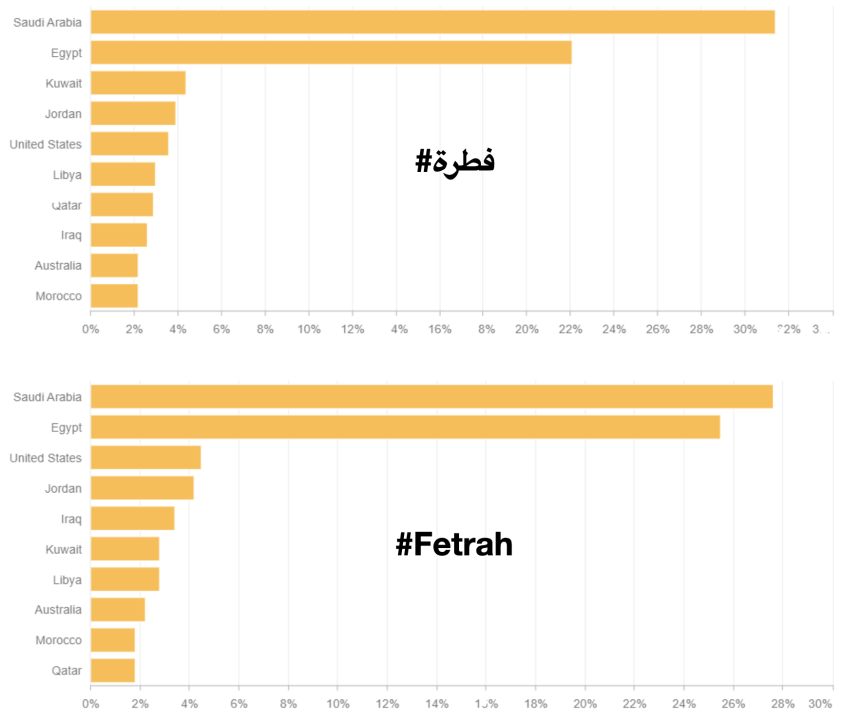

Data from Meltwater revealed that the top authors of tweets were in Saudi Arabia and Egypt. The campaign was also popular on Twitter among users in Kuwait, Jordan, Libya, Qatar, Iraq, Morocco, Australia, and the United States.

CrowdTangle data retrieved from Facebook pages, public groups, and verified profiles during the same period showed that the hashtag #فطرة received 1,514,155 interactions from 7,638 posts, and the hashtag #Fetrah received 602,353 in 3,830 posts.

Facebook pages appear to coordinate on anti-LGBTQ+ content

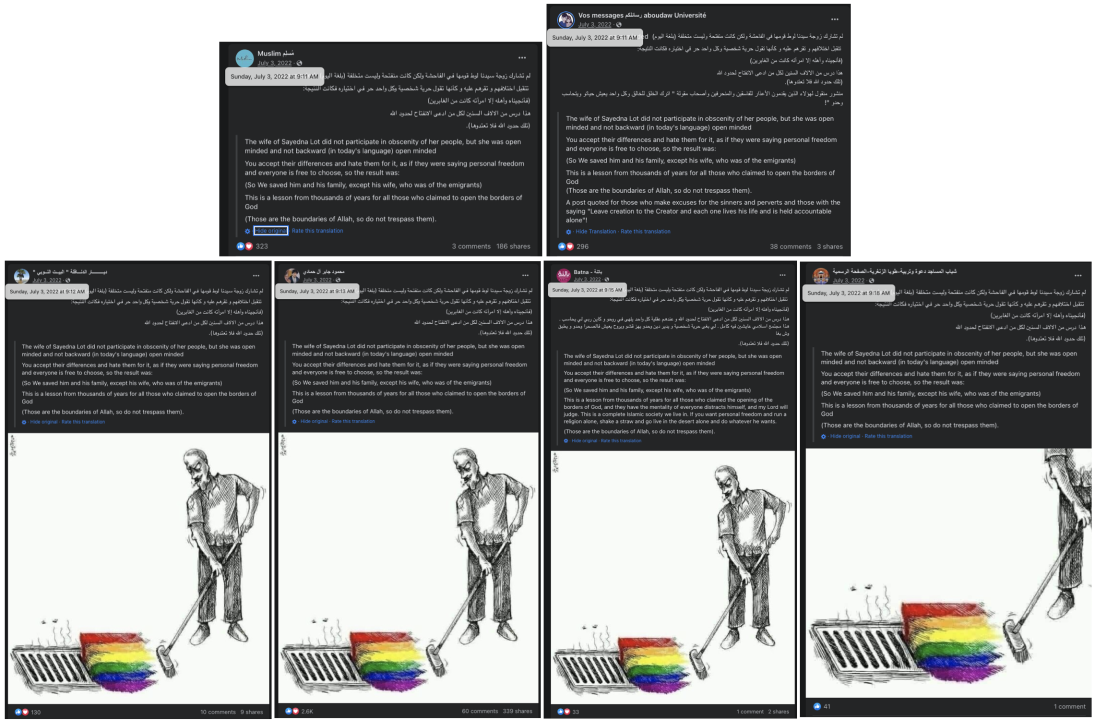

The DFRLab detected possible coordination between a group of Facebook pages and accounts sharing an identical anti-LGBTQ+ post and image, which began to spread on July 3, 2022, shortly after the Fetrah campaign launched. The post mentioned part of the story of the Prophet Lot, a prophet of God in the Quran, and specifically references his wife, who the post says was punished by God for being “open-minded” and not condemning homosexuality. Most of the pages that amplified this post included a graphic showing an illustration of a man sweeping rainbow-colored dirt down a street drainage system. Other posts shared Fetrah’s blue and pink graphics.

According to a CrowdTangle query, the total interactions on all the posts amounted to almost 100,000, while the posts’ reach across pages was significant given that the total number of page followers exceeded eighteen million.

A CrowdTangle query revealed that the original post was first shared at 08:36:29 EDT on July 3, 2022, by a page that uses both Arabic and Russian words in its name, أقنعني убеди меня, (“Convince me,” in Arabic and Russian). Within roughly one hour, twenty-four identical posts were published by other pages. Some posts were shared seconds and minutes apart. For example, two pages posted the content at 9:11:38 and 9:11:54 EDT. This pattern continued hours after the original post was published but then waned. The primary administrator location was Algeria for five of the first ten pages that published the post.

Conclusion

Government crackdowns and online campaigns are further fueling negative and hateful rhetoric that could lead to social exclusion and real-life violence against LGBTQ+ individuals, such as the targeting of Sarah Hegazi and others in the Middle East. In a region where LGBTQ+ people remain vulnerable and lack rights and protections, the increased spotlight can cause negative consequences with limited support to affected individuals. LGBTQ+ activists in the region face significant social and security risks from security forces and others, including their own families. Moreover, laws regulating nongovernmental organizations in several countries in the region prevent organizations that work to support LGBTQ+ people and advocate for their rights from registering and working in their countries. As anti-LGBTQ+ attacks increase in the region, more support mechanisms are needed to care for impacted individuals as they navigate difficult circumstances and discrimination from both governments and citizens in their societies.

Cite this case study:

Dina Sadek, “Anti-LGBTQ+ campaigns spread on Arabic social media,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), April 5, 2023, https://dfrlab.org/2023/04/05/anti-lgbtq-campaigns-spread-on-arabic-social-media.