Egyptian human rights defender repeatedly targeted by suspicious Twitter network

Campaign attempted to harass and discredit activist Gamal Eid

Egyptian human rights defender repeatedly targeted by suspicious Twitter network

Banner: Human rights activist Gamal Eid is seen at a court in Cairo, March 24, 2016. (Source: Reuters/Asmaa Waguih)

A potentially coordinated campaign targeted Egyptian human rights activist Gamal Eid at different times in 2022 and 2023. The campaign, led by a suspicious pro-government network previously identified by the DFRLab, used the hashtag #جمال_دولار (“Gamal dollar”) and replied to Eid’s account to spread claims that Eid received payments from foreign entities to betray his country. The network relied on identical or similar content to harass Eid within narrow timeframes.

Eid is an award-winning human rights defender who founded the now-closed Arab Network of Human Rights Information (ANHRI), one of Egypt’s oldest human rights organizations. Authorities have targeted Eid and other human rights defenders through a politically-motivated legal case used to crack down on civil society organizations, accusing them of illegally receiving foreign funding to destabilize the country. The case, which began in 2011, was condemned globally after it targeted several local and foreign NGOs in Egypt and sentenced forty-three Egyptian and foreign civil society workers to prison in 2013. Even though a retrial in 2018 acquitted the defendants, the second phase of the case continued targeting local Egyptian NGOs and its staff and used travel bans and the freezing of assets to suppress Eid and others. Eid was also physically attacked twice in 2019 by unknown armed men. Two pro-government TV presenters then mocked one of the attacks, claiming that Eid fabricated the incident.

The Egyptian government has severely repressed civil and human rights for a number of years. In 2021, the United Nations Human Rights Council called for an end of the current crackdown on peaceful activism and the release of thousands of political prisoners. Legal harassment of human rights organizations is often based on an oppressive 2019 NGO law which, according to the Project on Middle East Democracy, enables the government “to carry out supervisory control and broad discretion to regulate and dissolve civil society organizations.” After facing threats, arrests, and legal obstacles, ANHRI announced in early 2022 that the group would suspend its activities due to what it described as government restrictions used to limit its ability to conduct work.

The network of at least twenty-seven accounts attacking Eid was previously analyzed by the DFRLab after accounts in the network similarly targeted the late activist George Ishak for criticizing the government. The accounts, demonstrating multiple signs of inauthenticity, deployed tactics against Ishak including duplicated content, tweets within narrow timeframes, and high posting rates to amplify a specific hashtag. However, the campaign against Eid differs from the short-lived campaign targeting Ishak, as the latter took place over a period of two days, while attacks against Eid were repeated during different months and targeted the activist’s Twitter account. The network appears to include more accounts than previously reported, as more accounts attacked Eid than Ishak.

Hashtag trends

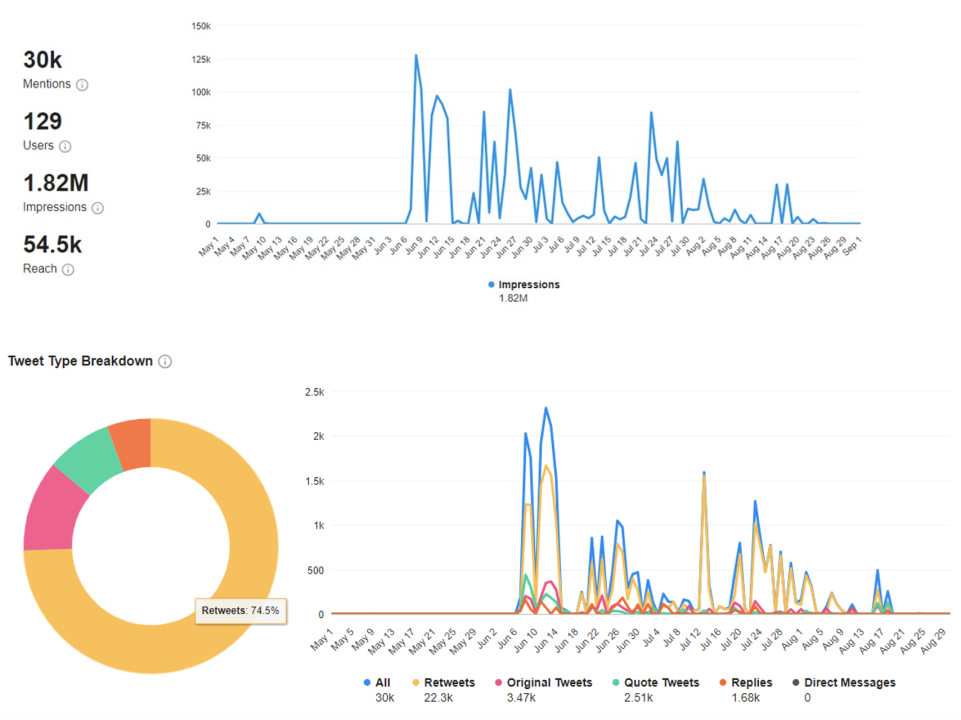

A Meltwater Explore query of the hashtag #جمال_دولار (“Gamal dollar”), which implies that Eid is a foreign agent receiving US dollars, revealed that the hashtag was mentioned by 137 unique users around 30,000 times in 2022 during May, June, July, and August. The hashtag was also used in 2023, but only thirteen times by thirteen users in March and April. Tweets using the hashtag mostly promoted a narrative that accused Eid, and sometimes other dissidents, of receiving foreign funding to destabilize the country, which aligns with legal accusations against the activist. Most mentions of the hashtag came from retweets (74.4 percent), quote tweets (8.4 percent), and replies (5.6 percent). Original tweets comprised 11.6 percent of hashtag mentions.

It appears that accounts focused on amplifying the hashtag on specific days and time intervals by retweeting and mass posting identical or similar text, likely to make the hashtag trend artificially. For example, on June 21, 2022, ten accounts amplified the hashtag 855 times over approximately one hour, eight of which used the hashtag more than seventy times each.

One account, @SolyRamly, promoted the hashtag by replying to other accounts using the same text, spreading the narrative accusing Eid of illegal foreign funding and calling him a traitor and a coward. The account used the hashtag 154 times in less than thirty minutes in June 21, 2022. Ten minutes after @SolyRamly stopped tweeting, the account @el_waledy started using the same exact text to tweet twenty-five identical replies within six minutes to accounts in the network, while also adding other hashtags directed towards different dissidents. Simultaneously, the account @SamiraEzzat1989 began quote tweeting other accounts, using the hashtag ninety times in less than twenty-five minutes.

This pattern was followed by other accounts during different days, which resulted in some accounts also having a suspiciously high rate of tweets using the hashtag. During different times in 2022, thirty-three accounts used the hashtag over one hundred times in one day. On June 12, twelve accounts used the hashtag more than one hundred times each, including two accounts using it more than two hundred times each. The hashtag appeared more than two thousand times between 12:23 PM and 3:31 PM local time that day, with no other activities during the rest of the day.

| Username | Number of tweets containing the hashtag |

| khaleda41971082 | 227 |

| mostafa122357 | 205 |

| mohamed32727714 | 199 |

| ezzmohamed403 | 179 |

| RamyAde70028215 | 174 |

| YaraElSherbiny9 | 150 |

| NesmaDwedar | 147 |

| ahm07349085 | 146 |

| Elgezery70 | 140 |

| Fadymalak93 | 123 |

| SamihAl84163810 | 117 |

| shadysa123321 | 117 |

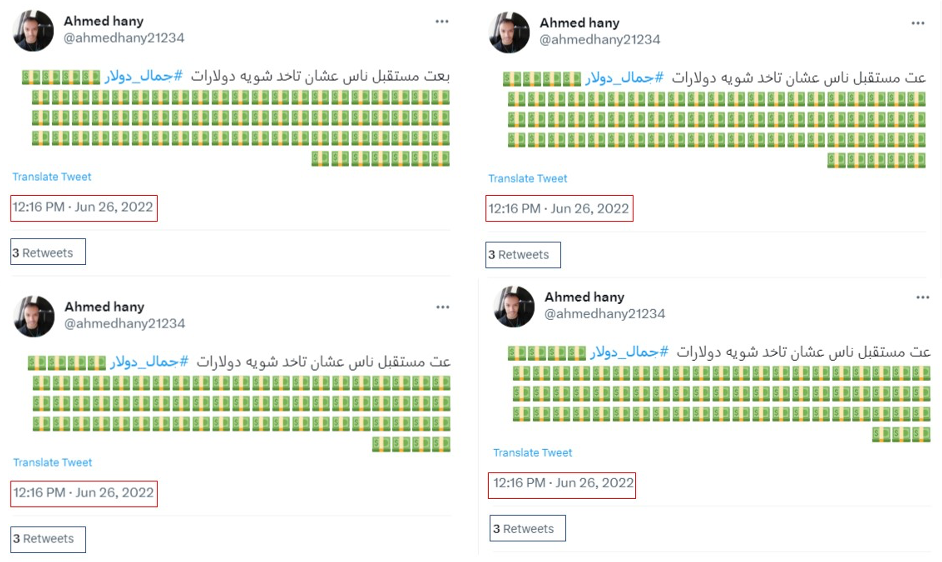

In another example, the account @ahmedhany21234, which uses a stolen photo of a musician as an avatar, posted the hashtag almost 1,500 times between June 8 and July 13, 2022. In late June and early July of that year the account tweeted the hashtag more than one hundred times on four separate days. For example, on June 25, the account used identical text in eighty-six original tweets within thirteen minutes. The tweets also featured repetitive use of a banknote emoji, the number of which decreased over time. The following day, the account changed the first word of the text tweeted it an additional sixteen times over three minutes, this time using a decreasing number of cash emojis. Moreover, six of these tweets received the same number of retweets from the same accounts, suggesting engagement coordination.

Screencaps showing four identical replies by the same account within one minute. The tweets received the same number of retweets. (Source: @ahmedhany21234 / archive, top left; @ahmedhany21234 / archive, top right; @ahmedhany21234 / archive, bottom left; @ahmedhany21234 / archive, bottom right)

Notably, the account @ahmedhany21234 engaged in similar tactics in the previous campaign targeting the late George Ishak. Other accounts like @AhmedYo99111294 and @MohamedE60996788 also targeted both human rights defenders.

Targeting Eid’s tweets

Accounts also directly attacked Gamal Eid by replying to his tweets. Replies sometimes included similar or identical content repeating similar accusations. According to Meltwater Explore data, the account @ahmedhany21234 replied to Eid’s tweets at least thirty-two times, often with the same text. The account also made replies, one minute apart, to unrelated tweets by activist Mona Seif and media outlet Mada Masr, using identical text that included the hashtag.

In 2023, the network responded to a tweet by Eid about the Belgian parliament’s condemnation of the human rights situation in Egypt, using similar replies that accused him of treason. Two users replied with identical text, accusing Eid of not verifying information and believing rumors targeting Egypt, while a third user replied with very similar content.

Identical graphics

Another sign of coordination was the network’s use of the same edited graphics. Accounts often posted a graphic showing a US $100 bill with Eid’s face replacing the face of Benjamin Franklin.

Meanwhile, a second graphic featured a picture of Eid with Egyptian human rights activist Hossam Bahgat, overlaid with the colors of the rainbow flag, followed by another image showing two gay characters from the movie The Yacoubian Building.

Stolen photos as Twitter avatars

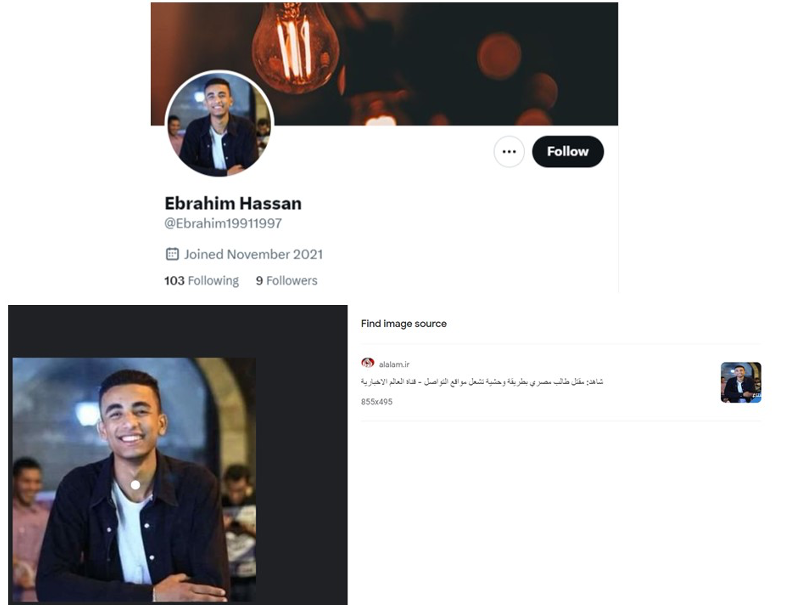

As noted in the DFRLab’s previous analysis of the network, many accounts relied on generic photos for avatars or did not use any images to maintain anonymity. Reverse image searches also revealed that some of the accounts used stolen photos of real people, often from news reports. For example, the avatar for the account @Ebrahim19911997 used a picture of an Egyptian student from a news report about the student’s death. Similarly, the account @hos88755213 also used a picture of a student, this time from Jordan, from a separate news report. Additional accounts featured a photo of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi.

As human rights defenders in Egypt continue to experience government persecution, investigations by the DFRLab demonstrate repeated instances of online targeting and harassment of prominent activists, in addition to efforts to push narratives aimed at discrediting them. In the case of Gamal Eid, our analysis identified repeated use of false and misleading narratives to discredit him, including narratives promoted by pro-government TV presenters.

More broadly, civil society organizations in Egypt continue to face repressive measures, especially under a new NGO law which requires human rights organizations to register with the government or be deemed unlawful. The law remains in effect despite calls by rights groups to amend it.

Cite this case study:

“Egyptian human rights defender repeatedly targeted by suspicious Twitter network,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), July 6, 2023, https://dfrlab.org/2023/07/06/egyptian-human-rights-defender-repeatedly-targeted-by-suspicious-twitter-network.