Pro-government Twitter accounts targeted head of Egyptian Engineers Syndicate

Suspicious accounts used duplicated content to attack syndicate head Tarek el-Nabarawy

Pro-government Twitter accounts targeted head of Egyptian Engineers Syndicate

Banner: Tarek el-Nabarawy poses with supporters ahead of the Egyptian Engineers Syndicate vote, May 30, 2023. Facebook

As members of the Egyptian Engineers Syndicate prepared to cast their ballots in May 2023 in a vote of no-confidence against independent syndicate head Tarek el-Nabarawy, the DFRLab identified possible inauthentic amplification of two hashtags on Twitter attacking el-Nabarawy. The two hashtags were promoted by suspicious pro-government accounts that demonstrated a degree of content and engagement coordination, in addition to similarities to a previously identified suspicious Twitter network. Accounts used identical and similar text, within narrow timeframes, to promote narratives discrediting the head of the syndicate.

At times, professional syndicates and unions played alternative political roles in Egypt as its heads voted in important bodies and its buildings were used to provide protection and organizing spaces, to some extent, to its members, given that police access to syndicates is strictly regulated by law. Thus, controlling syndicates is important for both the government and opposition. While the former regime of Hosni Mubarak often allowed the opposition, especially the now-banned Muslim Brotherhood, to use syndicates politically, Egypt’s current regime has restricted syndicates as a part of its crackdown on civil society. In 2016, the current regime stormed the Journalists Syndicate for the first time in the syndicate’s history and arrested two journalists who were inside.

According to Egyptian media outlet Mada Masr, conflicts between el-Nabarawy and the syndicate’s board members, who belong to the state-aligned Nation’s Future Party, resulted in a decision by the board to put forward an emergency meeting for its members to hold a vote of no-confidence on May 30, 2023, to push el-Nabarawy out. Despite efforts by the party to use its network to mobilize engineers against el-Nabarawy, initial results of votes on that day showed overwhelming support for the current head of the syndicate. Yet, before the final results were announced, a group of individuals stormed the hall where votes were being counted. These individuals assaulted voting officers and broke ballot boxes, preventing judges from announcing results.

Using videos taken of the attacks, fact-checking outlets Saheeh Masr and Matsda2sh (“Don’t believe”) revealed the identities of some of the attackers, among whom they found Nation’s Future Party Members of Parliament (MPs) and members of the party not associated with the syndicate. In response, the party posted a statement that its members and MPs who were present were engineers and members of the syndicate, which Saheeh Masr then refuted. In that report, Saheeh Masr identified the professions of identified members, all of which were not engineers. The syndicate’s statement, seemingly coming from the board, condemned the events and blamed el-Nabarawy and his supporters for the attacks, yet such accusations attempt to play both sides, given that initial results showed overwhelming support for the syndicate head.

The events led el-Nabarawy to file charges against board members, holding them responsible for the assaults, while some board members and members of Nation’s Future Party submitted similar charges against el-Nabarawy. Eventually, the government intervened on June 6 and supported el-Nabarawy, after which six key board members resigned.

Meanwhile, two hashtags #يسقط_نقيب_المهندسين (“Down with the head of engineers”) and #نعم_لسحب_الثقه (“Yes to withdrawal of confidence”) emerged on Twitter and amplified certain narratives against el-Nabarawy during and after voting, likely attempting to sway voters to vote no-confidence in the current head.

According to digital market intelligence company SimilarWeb, Facebook is the most visited social media network website in Egypt as of June 2023, followed by WhatsApp and Instagram, while Twitter was ranked fourth. Previous research from the DFRLab, however, demonstrated the frequency of Egyptian disinformation campaigns on Twitter specifically and the ability of networks to push hashtags to the platform’s trends list. While observers have noted that Twitter may have influenced the Egyptian Revolution in 2011, the extent to which Twitter aided activists during the revolution remains open to debate. Similarly, the extent to which the Twitter activity might have impacted the syndicate’s no-confidence vote is unknown.

A Twitter network coordinated on timing for hashtag campaign

Many of the accounts that promoted the hashtags demonstrated suspicious indicators that raise questions of coordination: they pushed duplicated content within narrow timeframes, posted at high rates, and promoted the same links and graphics.

Notably, some suspicious accounts in a network previously identified by the DFRLab took part in the campaign against el-Nabarawy, repeating similar tactics they had used to launch and promote hashtags attacking activists George Ishak and Gamal Eid.

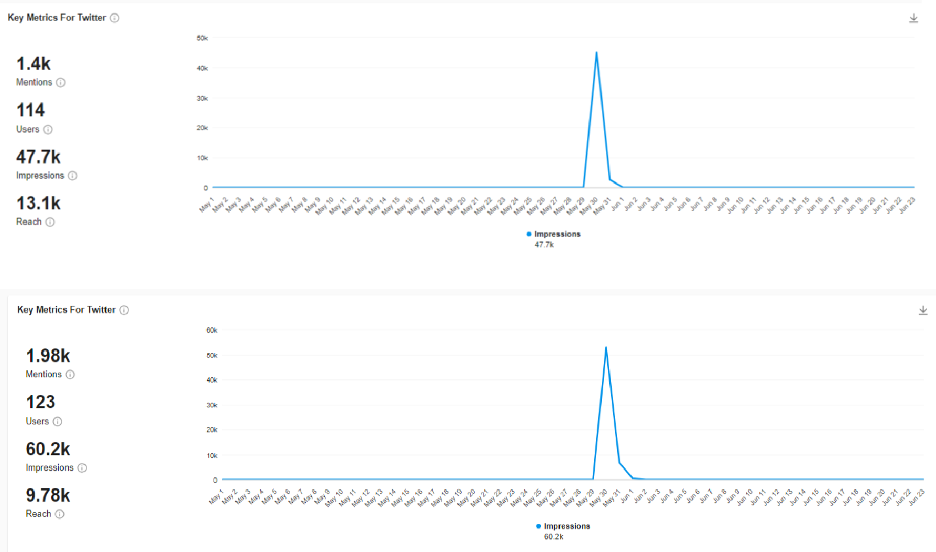

Data from monitoring tool Meltwater Explore revealed that the two more recent hashtags were short-lived, showing mentions for both hashtags on May 30 and 31, 2023, before quickly fading, suggesting that the accounts could have been activated to specifically amplify these hashtags during voting and one day after.

Discrediting narratives

Further analysis revealed that the majority of the posts using the two hashtags targeted el-Nabarawy with hostile narratives. On voting day, accounts accused el-Nabarawy of opposing the state and said that they would vote against him. Similar narratives claimed that the head of the syndicate is supported by the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood, while other accounts claimed that he is working for Al-Karama Party, a leftist opposition party. After the violent attacks on voting day, some accounts used the hashtags to amplify narratives accusing el-Nabarawy and his supporters of harassing voters and destroying ballot boxes.

For example, on voting day, the accounts @SarahTh26127182, @khamohamed4, @nourash60684114, @hagerabdozbnt, and @NadinKhalil328 all posted “copypasta”: the same exact text, to include the hashtags in the same order. The accounts tweeted saying that they would be voting to oust el-Nabarawy because he is acting against the government and only cares about his personal gains.

Four of the five accounts also tweeted copypasta claims that el-Nabarawy is opposing the government, adding that he is now a member of Al-Karama Party.

Some of the accounts also promoted links for videos by YouTube channel Press Center, which uploaded videos showing then-senior undersecretary of the syndicate Hossam Rizk talking about the syndicate and el-Nabarawy. Rizk was among those members of the syndicate’s board who resigned on June 6. Meanwhile, Press Center’s YouTube channel, which maintains a low number of subscribers, deleted all its videos sometime after the DFRLab archived its YouTube channel on June 21, 2023.

The accounts published links to three videos featuring Rizk in which he explains the rationale for a vote of no-confidence and criticizing el-Nabarawy. In one example, the four accounts @ahmedho88721101, @elseedymohamed5, @AlsawyBsnt, and @lyalansary1 published a link to a video titled: “Surprising | Senior Undersecretary of the syndicate reveals serious developments in the Egyptian Engineers Syndicate” minutes or even seconds apart. In their tweets promoting the video, all four of the accounts also used identical text claiming that decisions about the syndicate are dictated by the Al-Karama Party.

After the violent attacks, some accounts amplified the syndicate statement that blamed el-Nabarawy and his supportes for the attacks, claiming that he was abusing his power during the voting process. The accounts tweeted a picture of the statement in a period of twenty-three minutes.

On June 1, 2023, almost two hours after Nation’s Future Party published a statement on their Facebook page about the incident, several of the accounts that used the two hashtags tweeted a picture of the statement. The statement denied any involvement of the party in the violent attacks and assured that it would take legal action against those spreading false accusations. Among the accounts republishing the statement were @SlahMha, @fatmaelmarashy, and @LoayAnsary, which promoted it at the same minute alongside the hashtag #مستقبل_وطن (“Nation’s Future”).

Moreover, a few accounts used the hashtags at high posting rates within a narrow timeframe on the same day to amplify it. Meltwater Explore data showed that five of the accounts in the network used both hashtags more than seventy-five times on May 30, 2023, and three of these five accounts used the hashtags over 100 times each. The account @amrkhal88250693 in particular used the hashtags 209 times combined with only five original tweets, one retweet, and 203 quote retweets. All quote retweets by the account only included the two hashtags. In a similar manner, the account @emytalaat18 used the two hashtags 163 times in less than one hour, with 161 quote retweets and two retweets.

Engagement coordination

Further analysis of the accounts revealed highly similar and sometimes matching timelines with the same order of retweets, suggesting engagement coordination between several accounts.

The DFRLab also noted at least six tweets attacking el-Nabarawy, two of which were tweeted in the same minute and that were all retweeted exactly nine times by the same accounts.

Previous network

Accounts using the two hashtags appear to be imitating similar campaigns by another Egyptian Twitter network previously detected by the DFRLab that attacked Egyptian human rights defenders Ishak and Eid. Some of the accounts that attacked the Egyptian activists also took part in the campaign against el-Nabarawy, suggesting some level of coordination between these accounts or that the network might be larger than previously reported. The account @AhmedYo99111294, for example, which took part in the two disinformation campaigns targeting Ishak and Eid, tweeted once using the two hashtags targeting the syndicate’s head. Similarly, @elseedymohamed5, which had earlier used a hashtag attacking Ishak many times, also used the two hashtags attacking el-Nabarawy ten times each.

The repetition of such campaigns and similarities in activities by suspicious Twitter accounts highlight a consistent pattern of using likely inauthentic networks to attack dissidents. More importantly, the above evidence demonstrated that the goals of such campaigns may not be limited to discrediting opposition figures but also to influence voters. This raises possibilities of similar tactics being used during future elections, such as the upcoming presidential elections in Egypt scheduled for December this year. In fact, the DFRLab previously noted similar efforts from a different Twitter network that sent a hashtag supporting another presidential term for Egypt’s President Abdelfattah El-Sisi to the top of the country’s trending topics on Twitter in October 2022.

Cite this case study:

“Pro-government Twitter accounts targeted head of Egyptian Engineers Syndicate,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), October 19, 2023, https://dfrlab.org/2023/10/19/twitter-hashtags-egypt.