How information travels during Gaza’s communications blackouts

People in Gaza turn to eSIMS and other solutions amid cellular and internet outages

How information travels during Gaza’s communications blackouts

Share this story

Banner: A wounded woman uses a phone at Nasser Hospital after an airstrike in the city of Khan Yunis, Gaza Strip, November 3, 2023. (Source: DPA / Picture Alliance via Reuters Connect)

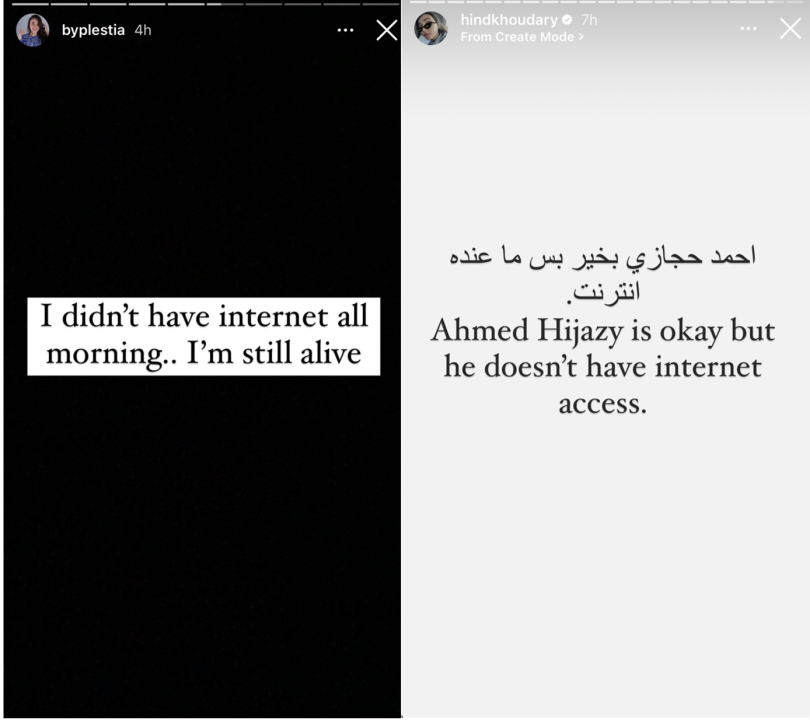

After nineteen hours of silence, social media users began to worry that something terrible had happened to Motaz Azaiza, a Palestinian journalist with more than 12 million Instagram followers who has become a key source for on-the-ground updates from Gaza during Israel’s ongoing bombardment of the strip. Eventually, Mohamed al Masri, another journalist in Gaza, managed to post an update about Azaiza. “Our friend Motaz Azaiza is fine and well,” he wrote, “but he does not have access to the internet or any means of communication. In fact, communication is missing in all parts of Gaza Strip.”

At around 6:00pm local time on October 27, 2023, Gaza plunged into an information blackout after Israeli airstrikes targeted the strip’s communications infrastructure. The Palestine Telecommunications Company, known as Paltel, and the Palestine Cellular Communications Company, known as Jawwal, issued a joint statement announcing the communications disruption. The two companies, owned by the same parent company, Paltel Group, are the largest internet service providers in Gaza.

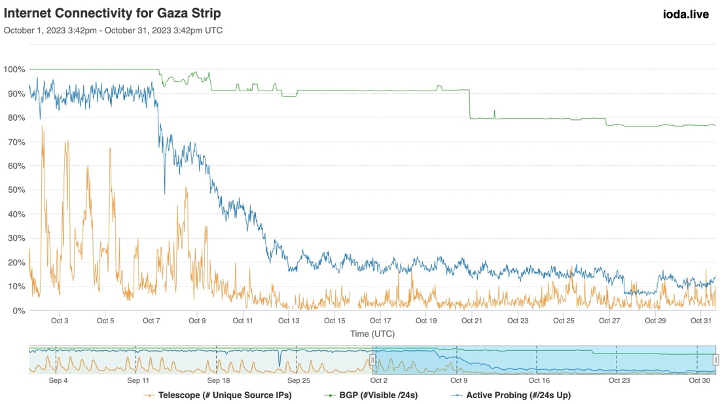

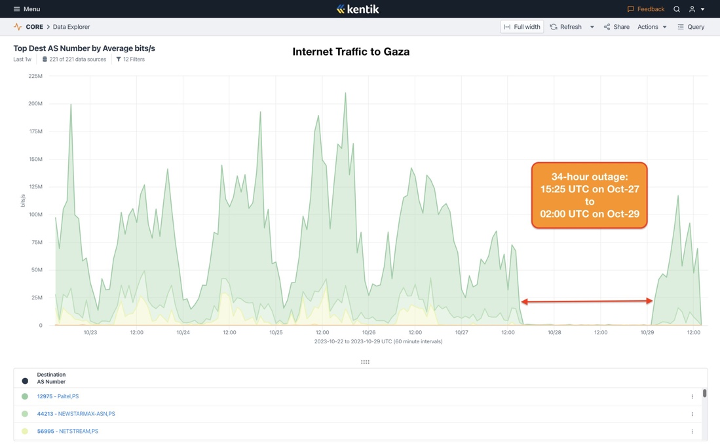

Internet traffic maps from Cloudflare, Kentik, and the Internet Outage Detection and Analysis project (IODA) all confirmed severe disruptions to internet traffic in Gaza. Cloudflare and Kentik both reported that disruptions were first evident at around 6:00pm local time. IODA noted fifteen autonomous system numbers and internet service providers suffered outages.

Thirty-four hours later, telecommunications service began to return to Gaza, albeit gradually. “Despite the challenging situation on the ground, our technical teams have been and continue to do everything in their power to repair the damage to the network to the best of their abilities and within the available resources,” Paltel and Jawwal noted.

In the days leading to the outage, Israel carried out two significant ground incursions into Gaza. Soon after the outage was first detected on October 27, Israeli Defense Forces spokesperson Daniel Hagari announced that the IDF was “expanding their ground operation this evening.” Around the time of the outage, the X account for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu shared an illustration of tunnels under Al-Shifa hospital—the largest hospital in Gaza, which doubles as a shelter for 60,000 people—alleging the underground labyrinth served as a base of operations for Hamas.

On October 28, as the communications blackout continued, Hagari issued an English-language message to the Arabic speaking population of Gaza, saying “For your immediate safety, we urge all residents of Northern Gaza and Gaza City to temporarily relocate south.” Journalists covering the conflict quickly raised questions as to how local residents were expected to receive the evacuation warning.

Taken together, the communications blackout and Israel’s statements sparked significant concern among supporters of Palestine and questions from journalists on social media as they demanded to know what was actually happening on the ground in Gaza.

“The cutting of communication to and within Gaza is designed to stop ppl from telling Hamas the location of Israeli troops,” noted Channel 4 international editor Lindsey Hilsum. “It also enables Israel to control the narrative as we are not seeing pictures of the civilians who are inevitably being killed.”

On November 1, a second communications outage occurred, disrupting phone and internet service. Paltel and Jawwal said it was “due to the targeting of the international routes, which had previously been reconnected.” Kentik, Cloudflare, and IOTA all confirmed the second internet outage, noting it lasted for about eight hours, from roughly 3:00am to 11:00am local time.

Methods of communication

In the immediate hours following the loss of internet access and cellular networks on October 27, the most consistent source of information came via satellite connectivity in the form of Al Jazeera journalists in Gaza who had prepared for this contingency.

At 6:46pm, journalist Tareq Abu Azzoum in Khan Younis reported:

We are going to be live by satellite as much as we can, in every single hour, so please guys, if you can hear us send that message to the world that we are isolated now in Gaza. Again guys, if you can hear us, we are isolated in the territory. We don’t have any phone signals. We don’t have any internet connections. We found a great difficulty even to communicate and contact with our relatives in different parts of the territory. Even we don’t know, like, how, what is the situation on the ground in different areas of the strip. We just only hear bombardment. We don’t have any kind of access of communication to anyone. Everyone now is really terrified and afraid.

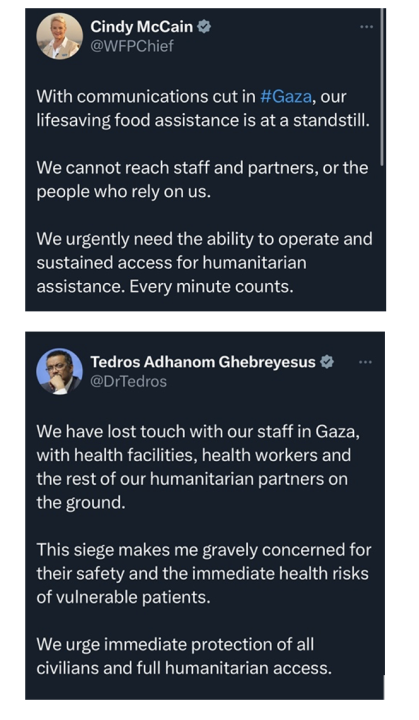

From social media users checking in on loved ones to humanitarian and media organizations trying to reach colleagues, Internet users outside of Gaza noted they had been unable to reach contacts in the strip that evening. The Palestine Red Crescent Society said it had lost all contact with its Gaza operations room and noted that “this disruption affects the central emergency number ‘101’ and hinders the arrival of ambulance vehicles to the wounded and injured.” Numerous humanitarian and aid organizations were unable to reach their staff, including Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), the Norwegian Refugee Council, and the United Nations’s World Health Organization, World Food Programme, and International Children’s Emergency Fund, among others. A number of news outlets, including the Washington Post and BBC, were also unable to reach their colleagues reporting from Gaza.

The most immediate consequence of the communications blackout was felt by people caught up in Israeli airstrikes that night who could no longer call ambulances for the injured. Attempting to find the wounded, paramedics drove towards the explosions. “The bombing of the telecommunications infrastructure places the civilian population in grave danger,” UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk later noted in a statement. “Ambulances and civil defense teams are no longer able to locate the injured, or the thousands of people estimated to be still under the rubble.”

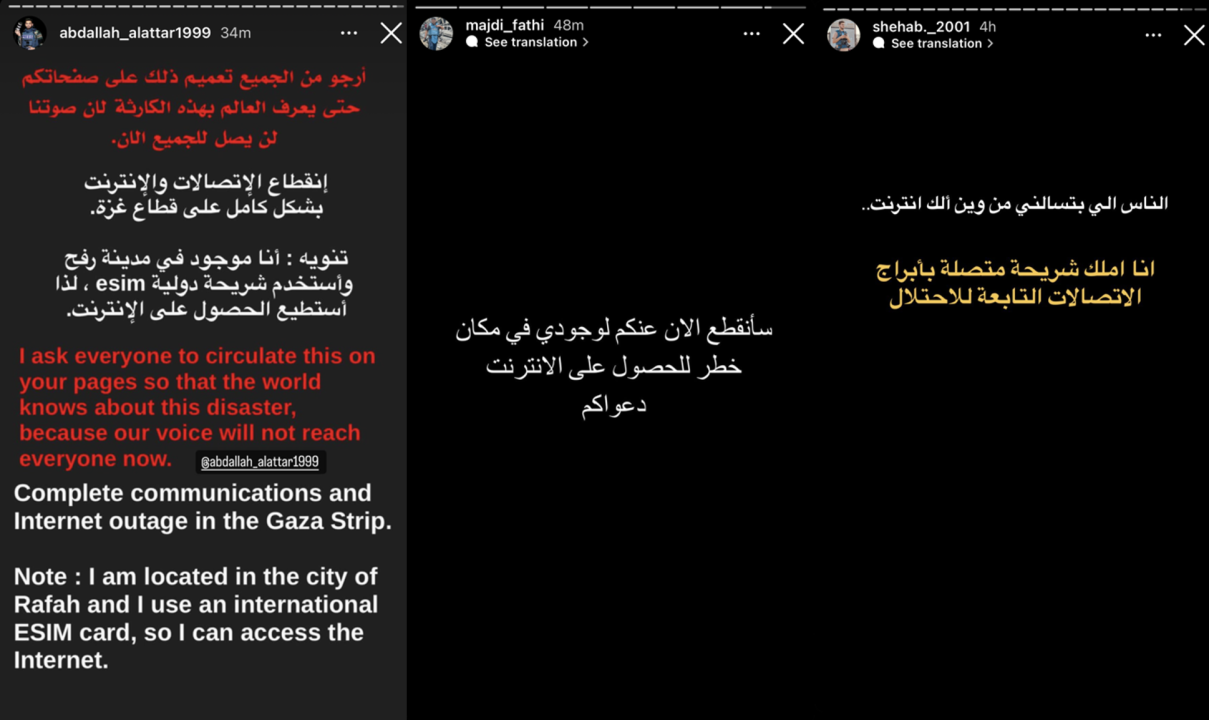

Beyond the handful of satellite connections maintained by media outlets and humanitarian organizations, the slow drip of information also came out of Gaza from those able to reach outside cellular networks, most commonly Egyptian or Israeli ones. Data roaming on international SIM cards became a primary communications method in the early hours of the outage. In two notable examples of messages emerging from Gaza, individuals used Turkish and American SIM cards as a means of reaching the outside world.

Journalists in Gaza also reported they were using and sharing Egyptian or Israeli SIM cards to transmit news. On October 28, reporter Mohammed Zaanoun posted to Instagram Stories, “I walked a long distance to be able to reach the Egyptian border, so I can send you this video and tell you that Gaza has been cut off from the world. There are no communications, there is not even a way to communicate with other family members internally.” He added that he would endeavor to upload one or two updates per day.

Looking for solutions

People without access to international SIM cards or neighboring networks in Egypt and Israel had to rely on more creative approaches. Al Jazeera reported on a man who stood in the background of their broadcast to communicate to his family that he was okay. An additional method of communication came through mosque loudspeakers—typically used to share calls to prayer. The BBC’s correspondent in Gaza reported that one FM radio station managed to continue broadcasting during the outage.

As the comms blackout carried on, demand grew for eSIMs – digital SIMs operating as virtual equivalents to physical SIM cards. eSIM usage grew as they appeared to be one of the most reliable methods of communication. However, they also came with challenges, the first being how to purchase an eSIM without an internet connection.

Egypt-based writer Mirna El Helbawi launched a grassroots effort to solve this problem by having people overseas purchase and donate eSIMs to Gaza. She asked those in Gaza with a connection set up hotspots so others could receive eSIMs. The initiative first focused on connecting journalists and medical staff in Gaza but has since expanded to allow anyone in Gaza to request an eSIM. As of November 2, El Helbawi said more than 2,500 donated eSIMs had been activated; she also noted that the eSIM providers Simly, Holafly and Numero had been the most reliable. Nomad, another eSIM provider, actively promoted its eSIMs for purchase but later noted it was struggling to keep up with demand.

Another challenge noted by El Helbawi is that connectivity varies across Gaza, with different neighborhoods requiring different eSIM providers, prompting her to begin mapping the neighborhoods in which each eSIM provider best operates. To ensure easy activation, another volunteer created the website gazaesims.com to provide step-by-step instructions, in addition to the creation of guides on how to activate eSIMs, as well as which phone models support eSIM functionality.

During the blackout, #starlinkforgaza began to trend on X. According to Twitter Trending Archive analytics for October 28, it was the second-longest trending hashtag and fourth most tweeted worldwide that day. X owner Elon Musk responded by saying it wasn’t clear who had the authority to permit the necessary ground terminals that are required to power Starlink, but said the satellite service “will support connectivity to internationally recognized aid organizations in Gaza.” Israel Communication Minister Shlomo Karhi responded to Musk, “Israel will use all means at its disposal to fight this.”

However, some in Palestine have instead pointed to neighboring Egypt to help with connectivity. Amid the second communications blackout on November 1, the Palestinian Ministry of Communications issued a statement saying it had exhausted “all possible solutions to restore communication” in Gaza and its only remaining option was to operate communication stations near Gaza’s borders and activate roaming services on Egyptian networks. The ministry appealed to Egypt to “expedite the implementation of this remaining option, given the critical humanitarian situation that cannot tolerate a prolonged loss of communication.” In one of his broadcasts from the Egyptian border, reporter Mohammed Zaanoun said, “I hope you can help us to deliver this message to the Egyptian people and the Egyptian president to put telecommunication towers near the Gaza-Egypt border, and to send SIM cards to Palestinians in Gaza, so that communication is possible.”

Three Egyptian telecommunications companies told Asharq Business that they have the technical capacity to use towers and mobile stations at the border to provide some service to Gaza, but said they are awaiting approval from Egypt’s National Telecom Regulatory Authority. An unnamed Vodafone Egypt official told Asharq that even if the services are established, the connection would be only serve those within twelve kilometers of a tower.

Israel maintains control over parts of Palestine’s telecommunications infrastructure, including equipment imports and frequencies (that limit bandwidth to 2G in Gaza and 3G in West Bank). In July 2022, a technical memorandum of understanding was signed by Israel and the Palestinian Authority (PA) with the goal of implementing 4G service across Palestine by the end of 2023. In July 2023, PA Communications Minister Ishaq Sidr maintained skepticism about the progress of the plan. “I’ve been [a] minister for over three years, and all we’ve heard is that 4G is going to happen,” Sidr told the Times of Israel. “All we hear are promises. We need to see something on the ground.”

The importance of information access

As communications services in Gaza were restored on October 29, it brought bad news for many after two nights of heavy bombardment. Fares Akram, a former Associated Press reporter based in Gaza, announced that many of his family members had died in an IDF airstrike.

Meanwhile, journalist Motaz Azaiza managed to get out a message for the first time since the start of the October 27 blackout, by way of his colleague Abdelhakim Abu Riash’s Instagram account on October 28. “I’m still alive,” he said, looking simultaneously anxious and relieved. “I didn’t get killed – yet.”

Having experienced two communication blackouts in six days, civilians, journalists, and humanitarian organizations in Gaza continue to lack dependable and uninterrupted internet and mobile services. In times of war, the heightened risk of internet shutdowns goes beyond disrupting methods of communication, as also it impedes vital access to life-saving services and interrupts the necessary documentation of events on the ground. Safeguarding internet and telecommunications infrastructure during times of war is imperative to protecting humanitarian services and information transparency.

Cite this case study:

Layla Mashkoor, “How information travels during Gaza’s communications blackouts,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), November 3, 2023, https://dfrlab.org/2023/11/03/how-information-travels-during-gazas-communications-blackouts.