Online campaign targeted Egyptian economist after his death in custody

Suspicious accounts on Facebook and X amplified state narratives about Ayman Hadhoud as human rights groups raised questions about his death

Online campaign targeted Egyptian economist after his death in custody

BANNER: Ayman Hadhoud’s Facebook profile picture. (Source: Ayman Hadhoud/Facebook)

To mark the second anniversary of the death of prominent Egyptian economist and government critic Ayman Hadhoud while in state custody, the DFRLab reviewed Facebook and X posts from 2022 to examine how a campaign exhibiting signs of inauthentic coordination attempted to undermine Hadhoud’s reputation posthumously. More than a dozen accounts posted identical or almost identical text, often within a short span of time, to amplify a government narrative that claimed, without evidence, that Hadhoud was mentally ill before his sudden death. Some of the X accounts that engaged in the smear campaign were previously identified by the DFRLab as being involved in other campaigns attacking Egyptian activists.

Hadhoud was an economist and member of the liberal Reform and Development Party. He was secretly detained in Cairo on February 5, 2022, and died suddenly at the age of 48 in a state-run mental health hospital one month later on March 5, 2022. Egyptian authorities denied any responsibility for his death. They claimed Hadhoud was arrested following “irresponsible behavior” during an attempted break-in at a Cairo apartment. However, a conflicting account of events shared by prosecutors claimed he was arrested for car theft in Daqahlia. According to a New York Times report, authorities claimed the economist had schizophrenia and “persecutory delusions, delusions of grandeur,” and was “raving incomprehensibly.” Authorities said the official cause of death was cardiac arrest and a possible Covid-19 infection.

Human Rights Watch contested the government’s account of events and said that authorities failed to conduct an “independent, effective, and transparent investigation” into Hadhoud’s mysterious death. Moreover, an investigation by Amnesty International, which included analysis by forensic experts, concluded that the evidence “strongly suggests that Ayman Hadhoud was tortured or otherwise ill-treated before his death.” The Egyptian police and security agencies have a long record of torturing critics. Hadhoud’s brother, who collected the body of the late researcher from the morgue, told The New York Times that he observed signs of abuse on Hadhoud’s body. He denied that Hadhoud had a mental illness.

In April 2022, the news of Hadhoud’s death under questionable circumstances sparked many criticisms of Egyptian authorities on social media. Some suggested that Hadhoud may have been arrested for his political activity as his economic research interests focused on corruption and the role of the military in the economy. Hadhoud had also previously written Facebook posts critical of the government. We identified social media accounts that joined these conversations and shared copy-pasta content on Facebook and X that amplified the government’s narrative about Hadhoud’s arrest and purported mental illness.

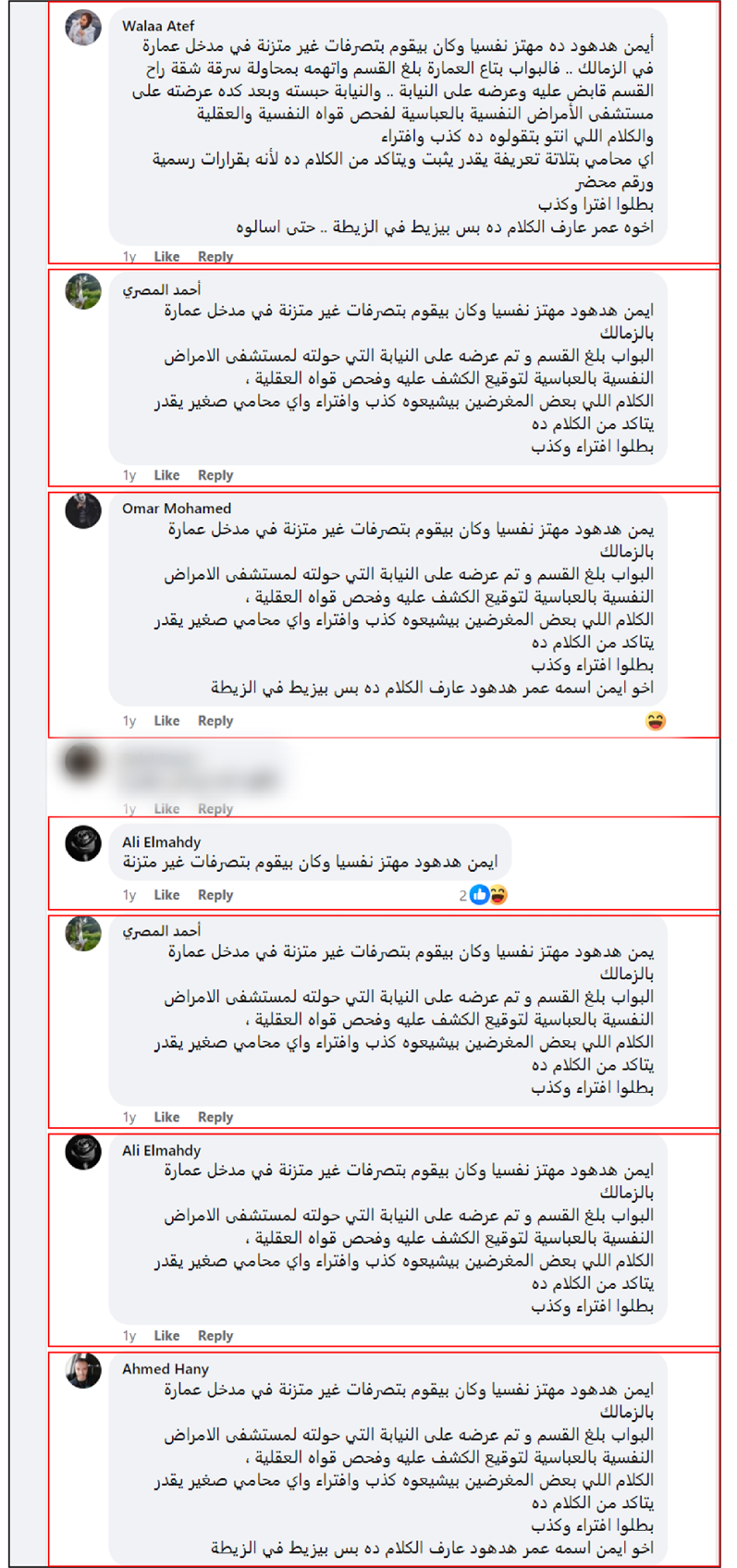

Verbatim comments on Facebook

The DFRLab identified sixteen Facebook accounts that posted nineteen identical or almost identical comments on the Facebook pages of independent media outlets, like Mada Masr, Al Manassa, and Al Mawkef Al Masry, the Reform and Development Party, and the rights group Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression. Some comments described the government’s narrative in extensive detail, while others provided shorter summaries. Many posts were shared over a short period, with several posted minutes apart.

For example, on April 9, 2022, the popular Facebook page Al Mawkef Al Masry published a Facebook post inquiring about the suspicious circumstances surrounding Hadhoud’s death. Two Facebook accounts replied to the post within a five-minute period, using the verbatim message, “Ayman Hadhoud was unstable and was engaging in erratic behavior at the entrance of a building in Zamalek. The doorman reported the incident to the police, and he was referred to the prosecution, which transferred him to the psychiatric hospital in Abbassia for a psychiatric examination to assess his mental abilities. The rumors being spread by some malicious individuals are false and baseless, and any small lawyer can verify this information. Stop spreading false accusation and lies.” A few minutes later, another account posted a similar but shorter message amplifying the same narrative.

In another example on Facebook, a post by the independent news outlet Mada Masr sharing news about Hadhoud’s case received seven almost identical comments from different accounts. Three accounts posted the exact comment that was shared on Al Mawkef Al Masry’s post.

Seven of the sixteen Facebook accounts that posted similar content had locked profiles and many used stock photos for their profile pictures. Furthermore, one of the locked accounts, Ahmed Hany, used the same name and stolen profile picture as an account on X, previously identified by the DFRLab as participating in a disinformation campaign targeting Egyptian activists, raising the possibility that the same person operates both accounts.

Government narrative amplified on X

The government’s narrative was also amplified on X in replies to users posting about Hadhoud’s case. Some of the accounts amplifying the narrative on X were previously identified as being part of a network engaging in disinformation campaigns targeting Egyptian activists Gamal Eid and George Ishak, using dubious tactics including anonymity, mass posting, and coordinated engagement. Some of these tactics were observed in the campaign against Hadhoud.

For example, a post by the account @KilledInEgypt received five similar replies pushing the same narrative that Hadhoud was mentally unstable. Two accounts, @lyalansary1 and @Mohamed11608116, posted identical replies to @KilledInEgypt one minute apart on April 10, 2022.

Other accounts mass replied to users on X discussing the case. The account @elseedymohamed5 posted nine identical replies within thirteen minutes on April 10, 2022. Many of the replies were posted seconds apart. On the same day, the account @atef_elmasre posted the same reply at least twenty-nine times in less than ten minutes.

Egyptian authorities closed Hadhoud’s legal case on June 1, 2022, leaving critical questions about the circumstances of his death remaining unanswered. This is despite independent investigations from human rights groups that contradicted the official narrative spread by the government and subsequently amplified on social media. Previous DFRLab research exposed the likely use of coordinated smear campaigns by Egyptian networks to attack dissidents and shape online narratives to align with the government’s perspective.

Cite this case study:

“Online campaign targeted Egyptian economist after his death in custody,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), March 4, 2024, https://dfrlab.org/2024/03/04/online-campaign-targeted-late-egyptian-economist.