Trends in China’s US election interference illustrate its longer game

Chinese malign information operations focusing on down-ballot Senate and House races rather than favoring a particular presidential candidate

Trends in China’s US election interference illustrate its longer game

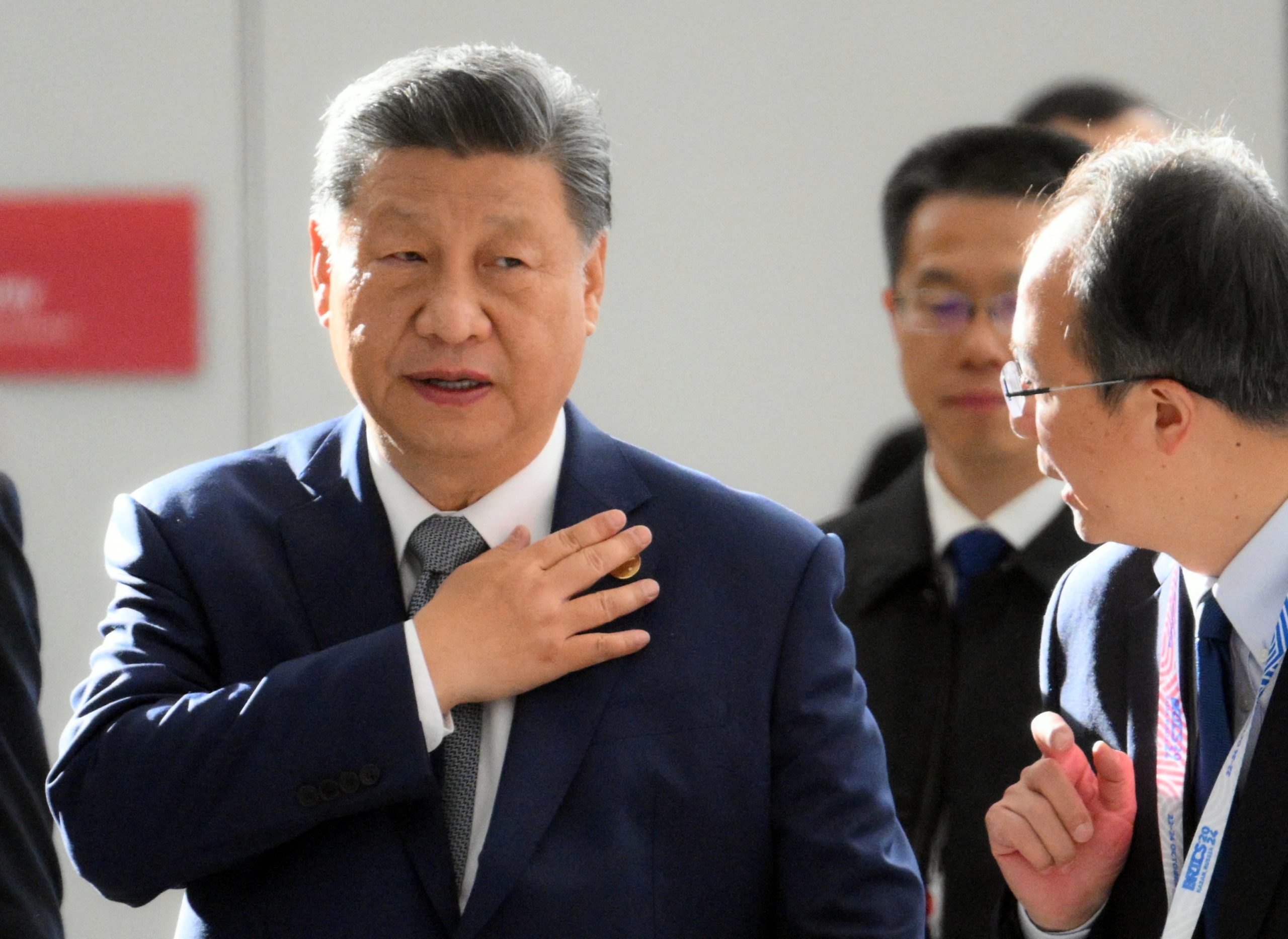

Banner: Chinese President Xi Jinping arrives at the BRICS summit in Kazan, Russia, October 24, 2024. (Source: Maksim Bogodvid/BRICS-RUSSIA2024.RU via Reuters Connect)

In the weeks and months leading up to the November 2024 US general election, government agencies and social media platforms have maintained a steady drumbeat of disclosures describing efforts by foreign threat actors to interfere with or otherwise influence the election. Not least among these actors is the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In contrast to Russian and Iranian state-linked assets, US intelligence assessments find that PRC state-linked actors do not seem to favor one candidate over another; rather, their main goal is to sow distrust in domestic democratic institutions and to capitalize on preexisting social divisions to weaken its adversary, the United States.

Below are five trends in PRC online influence operations in recent years and in the lead up to the 2024 US presidential election. While the intensity of online debate during elections makes them powerful vectors for digital forms of foreign malign influence, because Beijing is not tied to a specific electoral outcome, these trends are not necessarily time-bound by the election period and will likely continue into the post-election period and well beyond. This is because Beijing’s objectives for its online influence operations are part of a longer game: the gradual erosion of trust in democracy, and the destabilization of the United States. The PRC’s online influence activities are best understood with this longer-term goal in mind.

Focusing on down ballot races instead of the presidential election

This election cycle, China does not seem to have a preferred candidate for president. This is likely because both are seen as anti-China; one commentator described the choice as picking between two bowls of poison. Instead, the PRC has focused much of its covert influence efforts on denigrating specific down-ballot politicians it sees as particularly critical of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). This includes Reps. Barry Moore (R-AL) and Michael McCaul (R-TX), in addition to Sens. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) and Marco Rubio (R-FL). For example, PRC state-linked accounts on X accused McCaul of insider trading and abusing power for personal gain. McCaul chairs both the House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman and the China Task Force, which in 2020 released a report describing China as a “generational threat” and recommended over four hundred policy actions to curb CCP interests. He has also been a major supporter of continuing arms sales to Taiwan, and the Chinese government views visits by McCaul and other US officials to Taiwan as provocations.

The PRC’s focus on down-ballot elections reflects an understanding that US politics at the is becoming increasingly difficult to sway at a national level, as there is largely bipartisan consensus that the PRC is the United States’ chief adversary. China has thus begun to focus on more targeted influence efforts, including at the subnational level, as well as deploying more traditional offline modes of influence via the United Front Work Department and Chinese embassies. A recent report from the Jamestown Foundation outlines how embassy-organized pop-up events have targeted diaspora Chinese communities and traces how the same organizations that participate in these pop-ups have engaged in online propaganda and offline election-related organizing in the United States. One example included a United Front Work Organization in New York organizing a session to endorse a particular candidate for the local city council; these pop-up activities are highlighted and promoted via online social media campaigns.

Posing as real Americans and exploiting divisive social issues

In a departure from past tactics in which PRC-state linked actors mostly focused on spreading pro-CCP messages, these entities have increasingly been posing as real Americans as they engage in debates and stoke tensions over divisive social issues. Indeed, guidance from China’s Central Propaganda Department has emphasized the need to “localize” propaganda in a manner that resonates with target audiences in order to better spread China’s desired narratives. This is likely due to a recognition that past efforts at propaganda have failed to sway audiences to China’s side, in large part due to stilted, unappealing content.

Evidence that the PRC had begun to localize its efforts to influence US elections could be seen as early as 2022, when PRC-linked actors sought to meddle in certain congressional races. According to a 2021 report from the National Intelligence Council, the PRC government weighed whether or not to interfere in the 2020 election and ultimately decided not to as they viewed the consequences of exposure to be too great. However, disclosures from several platforms illustrate an increasing use of sockpuppet-style accounts that are engaging in salient political debates online.

For example, Microsoft’s Threat Analysis Center outlined in a recent report that the PRC-linked “Spamouflage” network had taken on the personas of American voters and was soliciting commentary on posts that touched on divisive domestic political issues, such as US policy on its southern border and the Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Hamas conflicts. Other accounts connected to the Spamouflage network have posed as Trump supporters and boosted conspiracy theories around the election, including claims that the 2024 election will be “stolen.” Given that the main aim of China’s influence operations vis-à-vis the United States is to sow disorder and capitalize on social divisions, we can expect these efforts to continue in the post-election period.

Studying and implementing influencer techniques to “go viral”

Chinese propagandists and actors have also been told to study and execute the use of influencers to understand how to gain views for content. This included guidance to shift from narrative or text-based strategies to short-form video, tactics that PRC propaganda officials have assessed are important for enhancing the appeal of CCP messaging. This effort has involved a wider array of actors in China’s propaganda apparatus: what was once the purview of China’s security services and propaganda bureau has now expanded to include commercial actors specializing in social media marketing and influencer cultivation.

For example, in July 2023, Mandiant revealed that a Chinese public relations firm had helped to finance two offline protests in the United States via a third-party freelance hiring website, as well as running a network of inauthentic newswire services designed to spread pro-China messaging. There is also an increasing focus on influencers in propaganda work, or “international communication,” as it’s referred to in the Chinese system, with the PRC supporting the development of influencer studios to cultivate both Chinese and foreign influencers to craft pro-PRC messaging that appeals to local (and often younger) audiences.

This strategy has met with some success. Some of these accounts on Western social media have millions of followers, and specific videos—including those focused on criticizing the Biden administration—have received hundreds of thousands of views. The pro-Trump network mentioned above—dubbed “MAGAflage” by the Institute of Strategic Dialogue—has been able to achieve a measure of virality with certain accounts by co-opting narratives from right-wing conspiracy theorists and having them reposted by organic accounts. For example, one of the identified MAGAflage accounts reposted a false story from Russia Today which claimed the Biden administration had sent a Neo-Nazi fighter to participate in the war in Ukraine. The MAGAflage post was retweeted by conspiracy theorist Alex Jones and viewed hundreds of thousands of times.

Leveraging generative AI tools to tailor and spread content

Another trend in CCP influence operations is the incorporation of generative AI tools. This trend follows longstanding guidance from Xi Jinping to better incorporate AI capabilities in online propaganda. The application of AI tools to online influence is not limited to content creation: generative AI is seen by the party as a means of solving a number of core problems with its propaganda apparatus, including the need to better tailor messaging to audience interests and styles of communication and the ability to spread as much content as possible on as many platforms as possible. It is also significant to what Chinese leaders now view as the defining struggle of contemporary geopolitics between China and the United States over global leadership.

The People’s Liberation Army, the military arm of the CCP, is assessing how best to incorporate AI capabilities into its cognitive warfare strategies, very likely including for use against the United States. In addition, Chinese entities are leveraging AI tools to aid in information operations, including to help in de-bugging and generating code, as well as employing SEO plugins and generative AI tools to produce article titles, utilize keywords, and autonomously rephrase plagiarized content to enhance search engine visibility while obscuring the original source of the material. In an April 2024 report, the state-run People’s Daily Online Research Institute highlighted the utility of AI tools in China’s overseas propaganda activities, including its use to improve the resonance and influence of the Party’s messaging and its ability to help messengers tailor their narratives to specific cultural contexts. For the foreseeable future, the PRC will likely show a sustained desire, intent, and effort to continue integrating AI applications and tools into its online influence efforts.

Targeting multiple platforms with more limited presence on TikTok

Part of China’s overall strategy for information operations online is to diversify the channels for dissemination, both as a means to avoid concentrating resources in a way that could be greatly impacted by a single takedown, and also as part of an effort to target and reach as many communities as possible. To illustrate, a August 2023 report by Meta of its takedown of PRC-linked assets outlined that it had identified a prolific influence network that spread thousands of assets across over fifty different platforms. This diversification is also reflected in China’s online influence efforts with regards to the 2024 election.

Despite the broad concerns stated by the national security community of the PRC leveraging the Chinese-owned app TikTok to conduct a major influence operation against Americans in the election period, PRC-attributed activities on the platform have been quite limited to date, especially when compared to Chinese operations on other platforms. Both Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) have had larger and more widespread PRC-attributed campaigns related to election influence than TikTok in 2024.

This is not to say influence campaigns have not appeared on TikTok–for example, a Graphika report from September 2024 outlined a Spamouflage-linked asset on TikTok that was spreading divisive messages ahead of the US election. At the same time, however, this was only one asset. And as the PRC’s stated strategy as well as trends in its online influence operations both illustrate, TikTok is not a singular vector for PRC efforts, nor has it been particularly effective in isolation.

Conclusion

In contrast to Russian and Iranian efforts vis-à-vis the upcoming US election, China does not have a preferred candidate, seeing both as having significant downsides. China’s is playing a longer game: its goal is the longer-term erosion of trust in democratic institutions, rather than a more acute threat to election infrastructure or direct influence on voting behavior. According to China’s cognitive warfare philosophy, wearing down the enemy from within—affecting their “will to fight”—is a key goal of information operations and influence activities. China’s online operations are growing more sophisticated, more targeted, and increasingly complimented by offline and cyber activities. Understanding the holistic and multifaceted nature of Chinese influence is thus critical to understanding what we can expect in the future, and for shaping strategies for resilience to CCP influence, both in the leadup to November 5 and beyond.

Cite this case study:

Kenton Thibaut, “Trends in China’s US election interference illustrate its longer game,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), November 4, 2024,