Kremlin media capitalizes on Latvia-Lithuania misunderstanding

Pro-Kremlin media took advantage of confusion between the Baltic countries over sourcing electricity from Belarus, propagating a narrative of disunity

Kremlin media capitalizes on Latvia-Lithuania misunderstanding

BANNER: (Source: @nikaaleksejeva/DFRLab)

When miscommunication created the impression that the Lithuanian and Latvian governments had taken divergent positions on a ban on electricity imports from Belarus and Russia, pro-Kremlin media outlets quickly propagate their own exaggerated story of dysfunction and infighting between the two Baltic countries.

The case demonstrated how Kremlin media capitalized on a case of crossed wires between the two Baltic allies. This case echoes previous instances when the Kremlin has exploited minor disagreements or miscommunication to amplify a narrative of extreme disruption between two other countries. The DFRLab also examined similar pro-Kremlin media tactics before, tactics that are common in the Baltic information environment.

No NPP Power Purchases

The root of the misunderstanding between the two countries was an article on Lithuanian media outlet 15min, which declared falsely that Latvia was open to electricity imports from “third world countries” (a backhanded reference to Belarus) and, in particular, from the Belarusian Nuclear Power Plant (NPP) in Astravyets. If Latvia were to pursue such a purchase, it would have to go around Lithuania’s import ban — as well as having literally to go around the latter country by importing through Russia — that is already in place on electricity from the as-yet-not-operating Astravyets NPP. In response to the article, Latvian authorities ensured that they would not bypass the ban. Because the communication between the two countries took place in the media, instead of through bilateral channels, pro-Kremlin media was able to insert its own spin into the conversation.

In February, Lithuania announced that it planned to ban electricity imports from “third world countries” once the Astravyets NPP becomes operational in 2020. Lithuania considers the nuclear facility dangerous, as it sits just 40 kilometers outside of its capital city, Vilnius, and, being outside of the European Union’s safety protocols, there is no guarantee as to the integrity of its construction.

Meanwhile, on August 13, the Latvian Ministry of Economics, which is responsible for the country’s economic policy, announced that it had decided to allow electricity imports from “third world countries” once Lithuania closed the only import route from the Baltic states. The Latvian government stated that doing so allowed it to “safeguard” its ability to make “timely decisions,” in the event that Lithuania’s decision to close down the trade route “disrupt[s] the power supply or increase[s] the price of electricity.”

Lithuanian President Gitanas Nauseda issued a public response to Latvia’s decision. In a press conference with German Chancellor Angela Merkel on August 14, 2019, in Berlin, Nauseda said:

The Latvians made a political decision. As far as I am aware, there had been some consultations with Lithuania’s Energy Ministry, but the decision was made before consultations were concluded, which is why the only thing left in this situation is regret.

The next day, Latvian Prime Minister Krisjanis Karins told the Latvian TV channel LNT that Nauseda’s statement indicated a “misunderstanding.” Karins said:

I am afraid he [Nauseda] may not be fully aware of what is happening. I can reiterate, the Latvian government has not decided to buy electricity from Belarus. That is not the case at all.

The same day, Latvian public media outlet LSM wrote an article in response to Nauseda’s comment with the following headline: “The Ministry: Latvia Does Not Plan to Buy Electricity from the New Belarussian NPP in Particular.” In the article, Dzintars Kaulins, the Deputy State Secretary of the Ministry of Economics of Latvia, explained that “trading is anonymous within the stock exchange. This means that Latvia does not buy electricity produced by a specific power plant. But for consumers, such a decision will mean price stability.”

Producers can sell electricity to retailers in one of two ways. First, they can sell a fixed supply — a finite amount — based on a “mutual agreement” between both parties. Second, they can engage in an “electricity exchange,” which takes into account the “interaction of user/buyer demand and producer/seller supply.” If Latvia agrees to fixed supply deals with producers from Russia and Belarus, it can avoid buying electricity from the Astravyets NPP.

Arvydas Sekmokas, Lithuania’s former Minister of Energy, expressed concern to Lithuanian news outlet 15min that Latvia’s electricity supplier “Spectrum Baltic” will buy electricity from the Russian supplier “Baltiyskaya AES,” which can sell electricity produced by the Astravyets NPP. “Spectrum Baltic” has already signed a preliminary non-binding electricity purchase-sale contract with “Baltiyskaya AES,” according to media reports.

The Latvian government assures that it will comply with Lithuania’s ban on energy from the Astravyets NPP and that it is considering buying electricity solely from producers in Russia; the Lithuanian government, however, is skeptical.

Media Coverage

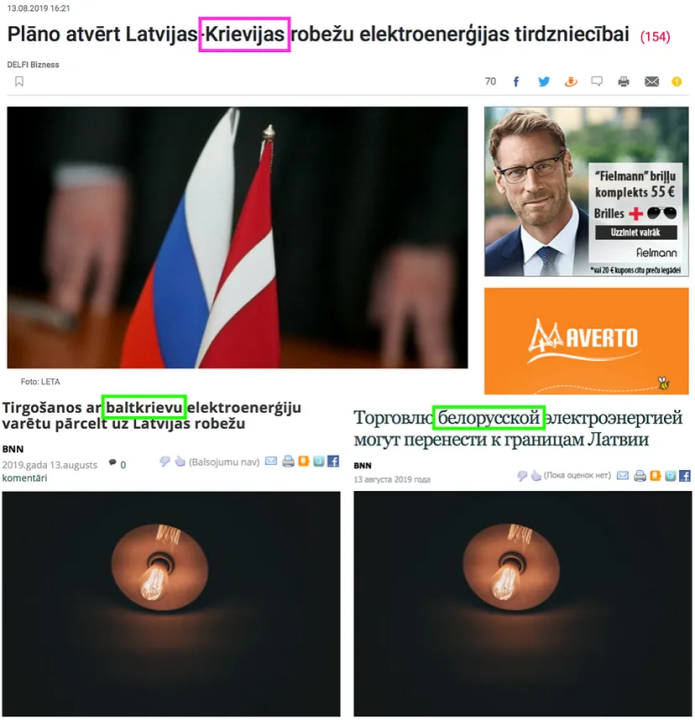

Inconsistent reporting on the Latvian government’s decision began on August 13, the day of the announcement, with popular online news outlet Delfi.lv and international news agency BNN both devoting coverage to it. Delfi.lv’s article stated that Latvia is opening its border to trade electricity with Russia, while BNN reported, in both Latvian and Russian, that Latvia may elect to trade electricity with Belarus instead.

Two news items drew the inaccurate conclusion that Latvia had decided to buy electricity from the Astravyets NPP. First, Ernestas Naprys, a journalist with 15min, published the article titled, “Latvians Will Buy Eastern Electricity Bypassing Lithuania — Astravyets NPP Blockade Fades.” Second, Nauseda gave a comment about the Latvian decision to Latvian outlet LRT.

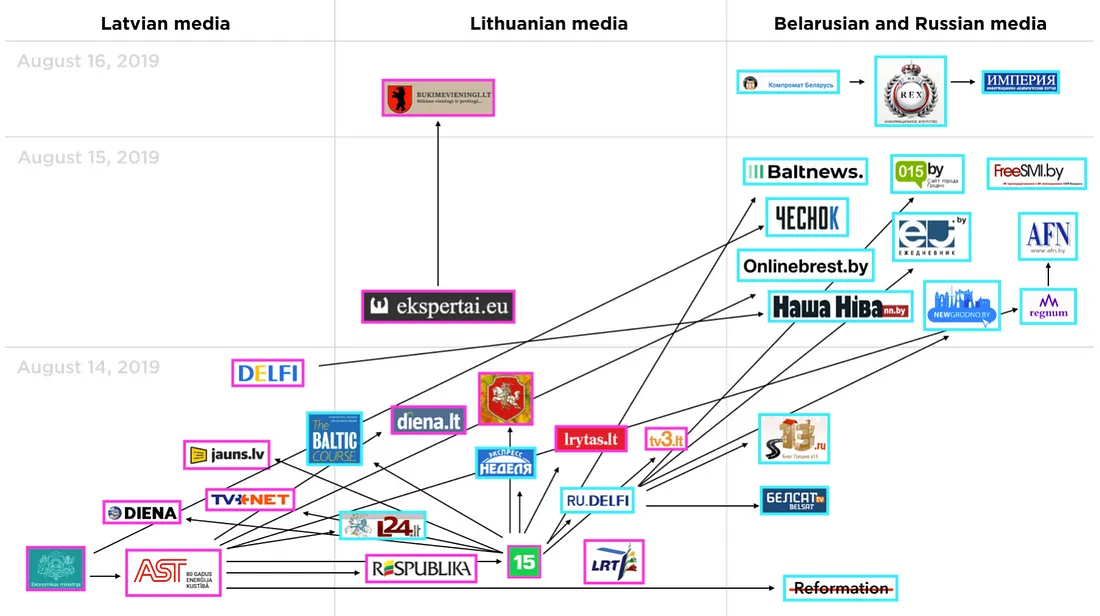

The DFRLab conducted a media spread network analysis for articles suggesting that Latvia would buy electricity from Astravyets NPP.

At least nine media outlets picked up the news about Latvia buying electricity from Astravyets NPP directly from 15min, while at least five news outlets in Belarus cited a second article published by the Russian version of Delfi.lt. The spread analysis also revealed that Latvian media picked up the story from Lithuanian outlets the same day as the story initially appeared, while most of the Belarusian outlets published the story one day after it first emerged. Some articles relied on press releases from the Latvian Ministry of Economics and the AST, Latvia’s national energy distribution company.

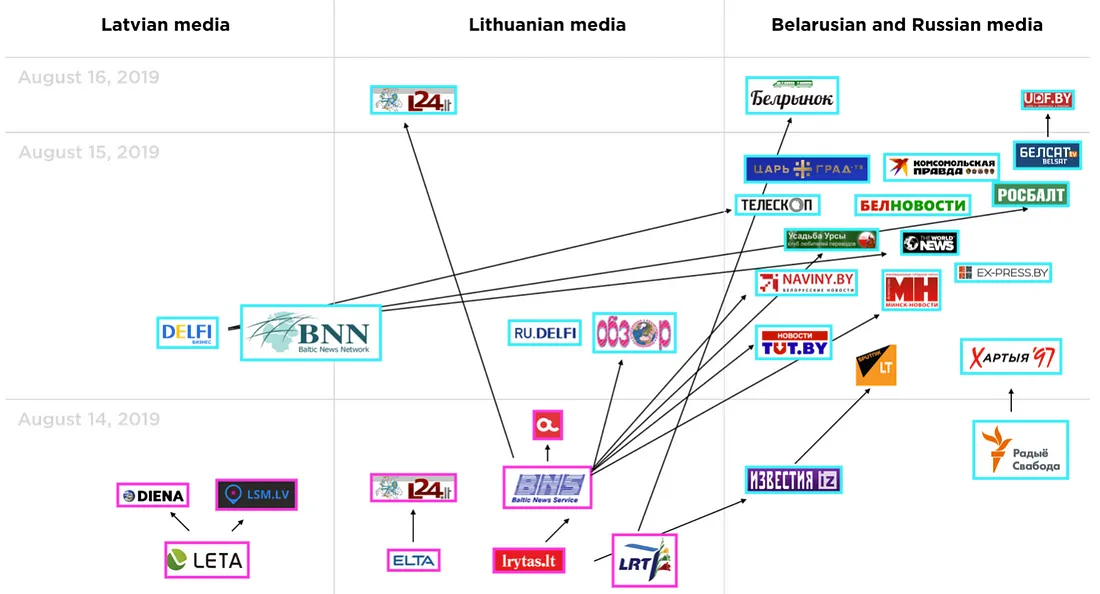

Nauseda’s comment spread according to a similar pattern. The comment was initially published in a Lithuanian outlet and began to spread in Russian outlets the next day.

Many media outlets picked up Nauseda’s comment at the press conference independently. The most popular news source reporting on the comment was BNS news agency. Both Latvian and Lithuanian media amplified Nauseda’s comment less than they did Naprys’s article.

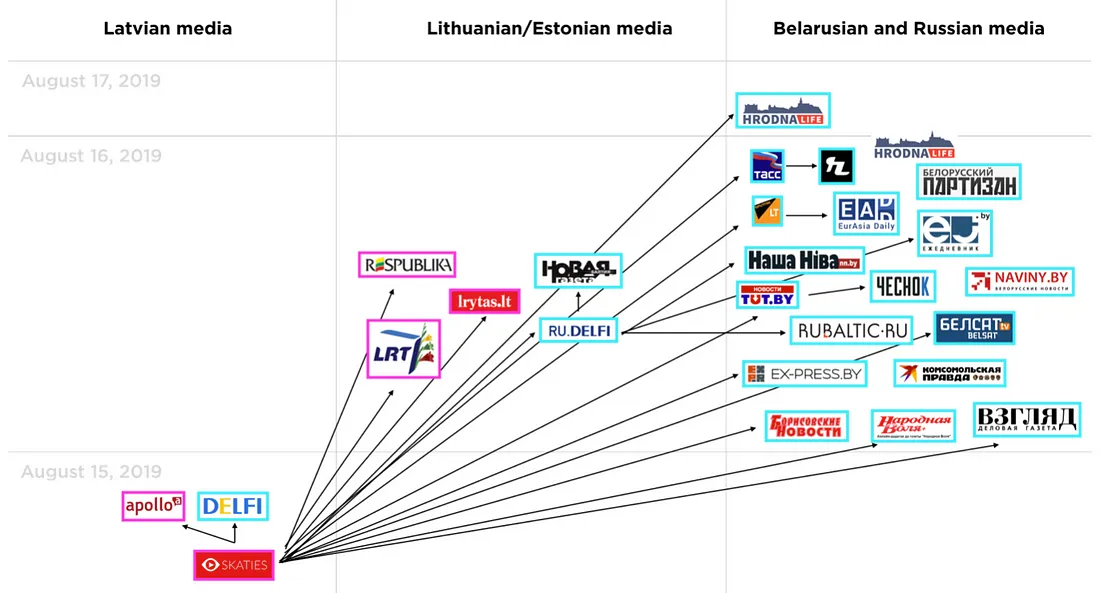

The DFRLab conducted a news spread analysis of the Latvian Prime Minister Karins’s denial that Latvia intended to buy electricity from the Astravyets NPP.

Interestingly, news of Karins’s comment spread mostly on Belarus and Russian media outlets. The DFRLab identified just four publications in Lithuanian media. In Latvia, it was only after the Latvian media outlet Skaties.lv published LNT’s original story that another two outlets followed suit, doing so the same day.

Kremlin Media

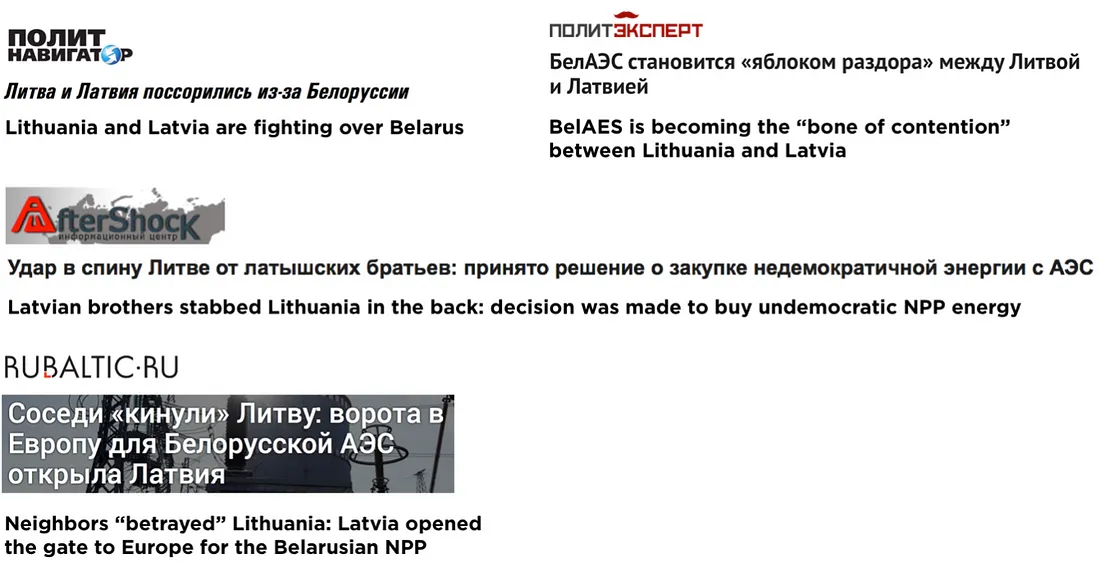

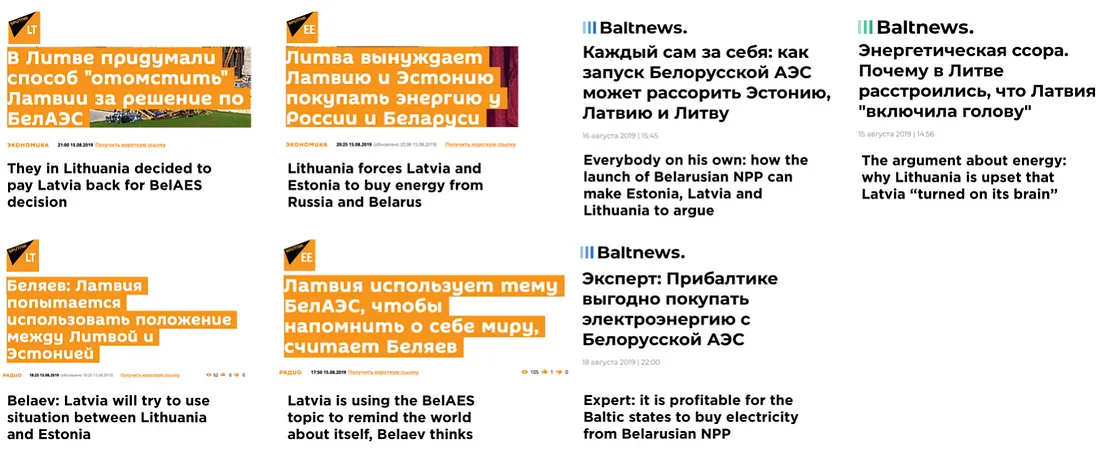

Kremlin-owned and pro-Kremlin media outlets that covered the issue barely engaged in disseminating the story as it originated in Lithuania and Latvia. Instead, these outlets created new, emotionally charged narratives.

The most common of these narratives asserted that the “Baltic Brothers,” once a united front, are now fighting with one another. At least four articles reflected this narrative.

Another popular narrative among pro-Kremlin media characterized Lithuania as a victim and a loser. Four media outlets reflected this narrative. The pro-Kremlin outlet Vzglyad, for example, published a story alleging that Lithuania had lost the “nuclear bet” with Russia and Belarus; pro-Kremlin outlet Rambler and fringe outlet Energy Media both republished it.

Kremlin-owned media outlets in the Baltic states — specifically, Sputnik and Baltnews — did not spread a unified narrative but did reinforce an overarching theme that Lithuania was wrong, while Russia and Belarus were right.

Conclusion

Pro-Kremlin media took a simple miscommunication between the Latvian and Lithuanian governments on buying electricity produced by the Astravyets NPP in neighboring Belarus and misrepresented it as a genuine disagreement between the two Baltic allies. Supplementing news articles with long-form feature articles and opinion pieces by pro-Kremlin experts, a common Kremlin influence tactic, helped contort the narrative into one of Baltic disunity, in line with the Kremlin’s interests.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.