Twitter’s Hong Kong Archives: Chinese Commercial Bots at Work

Chinese information operation mobilized commercial bot accounts to target Hong Kong pro-democracy protests

Twitter’s Hong Kong Archives: Chinese Commercial Bots at Work

BANNER: (Source: @KaranKanishk/DFRLab)

On August 19, Twitter released an archive of 936 accounts it attributed to a “significant state-backed information operation focused on the situation in Hong Kong.” The accounts violated the platform’s manipulation policies, which prohibit spam, coordinated activity, fake accounts, attributed activity, and ban evasion.

In its statement, Twitter said:

The accounts we are sharing today represent the most active portions of this campaign; a larger, spammy network of approximately 200,000 accounts — many created following our initial suspensions — were proactively suspended before they were substantially active on the service.

It also noted that some of the accounts had IP addresses originating in mainland China:

As Twitter is blocked in PRC, many of these accounts accessed Twitter using VPNs. However, some accounts accessed Twitter from specific unblocked IP addresses originating in mainland China.

The DFRLab’s analysis revealed that many of the accounts in Twitter’s archive also used tactics similar to that of a commercial bot network. In particular, some of the automated accounts deployed to target the Hong Kong protests had a history of use for commercial purposes, such as posting spam-like promotional links in high volume.

Analyses of Chinese online propaganda efforts to date have mostly focused on the Communist Party’s use of a human-run, nationalist troll army, often called wumao, or the “50 cents.” The DFRLab’s analysis of this archive, however, concentrates on the use of commercial bot accounts originating within mainland China, which has been less well-studied.

Targeting the Hong Kong Protests

A tweet by one of these commercial-origin accounts, for example, invoked the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance (FOO), a controversial amendment to Hong Kong’s extradition legislation that would allow extradition of fugitives from Hong Kong to mainland China, Macau, and Taiwan. The proposed amendment was the initial catalyst for the current protests, as pro-democracy activists worried that officials could wield it to silence the Chinese government’s critics in Hong Kong. While Hong Kong officials suspended the amendment in June, when the protests first began, they have not officially withdrawn it, which remains one of the protestors’ five chief demands.

The tweet emphasized that Hong Kong natives, along with “anti-China forces” such as the United States, had unnecessarily politicized the proposed extradition amendment.

Translated from Cantonese, the tweet reads: “The Extradition Bill was supposed to be a simple legislative adjustment but came under massive attack from the opposition. Taiwanese forces have interfered; U.S. & EU forces are paying ‘special attention’ to the situation; there were signs of support from anti-China forces from abroad [exiled]. All of this has turned the streets of Hong Kong into a space for ‘radical’ political confrontation and anti-china protests.”

Another tweet underscored the threat the Hong Kong protestors pose to law and order in the city.

Translated from Cantonese, this tweet reads: “The (violent) protestors have continuously occupied the streets, seriously damaging Hong Kong’s civil security and hurting police officers. On July 1, they exerted significantly violent actions, breaking in and damaging the Legislative Council Complex, which opposition senators instigated by not only not preventing the violent escalation but urging police officers to use restraint and providing the protesters with human and material resources.”

The tweet also added that the Hong Kong police had no other choice but to enforce the law against the violent protestors. The Hong Kong police have faced widespread condemnation from international media and human rights groups on their use of force to quell the protests.

Targeting Guo Wengui

The Hong Kong protests were not the first time the Chinese accounts in this archive were mobilized for political ends.

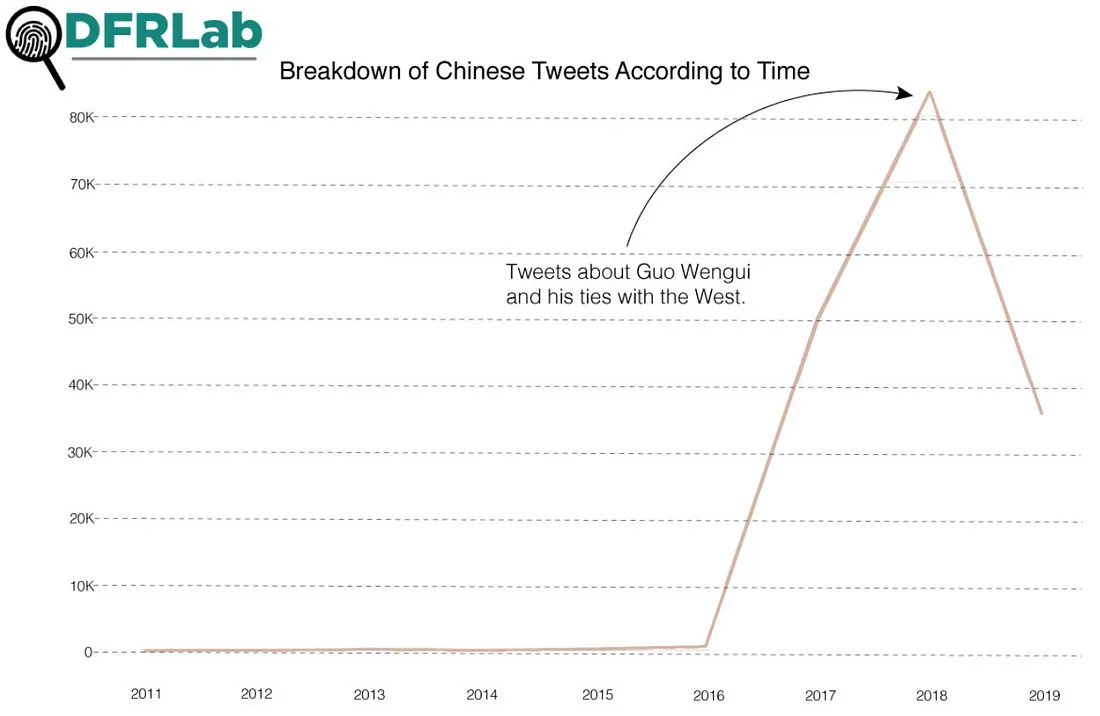

Tweets in Chinese first started appearing after 2016, peaking in mid-2017 to 2018. Many of these tweets targeted Chinese billionaire Guo Wengui, who fled to the United States after falling out with the Communist Party’s leadership.

In 2017, the Daily Beast reported that a Twitter bot army had been trolling Wengui.

Coincidentally, Wengui’s name has now surfaced again in connection with the Hong Kong protests. In the United States, Wengui has enjoyed a close relationship with former White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon. The two have announced plans to set up a fund to investigate corruption in China. Now, in the context of protests in Hong Kong, a conspiracy theory video circulating on YouTube alleges that Wengui and Bannon have masterminded the pro-democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong. The video has amassed nearly 60,000 views.

The DFRLab did not find any evidence to suggest that the accounts in this archive pushed the conspiracy theory about Wengui’s connection to the protests, however.

A Commercial, Automated Network

The DFRLab discovered several indicators that many of the accounts in this archive may have been both automated and commercial in nature.

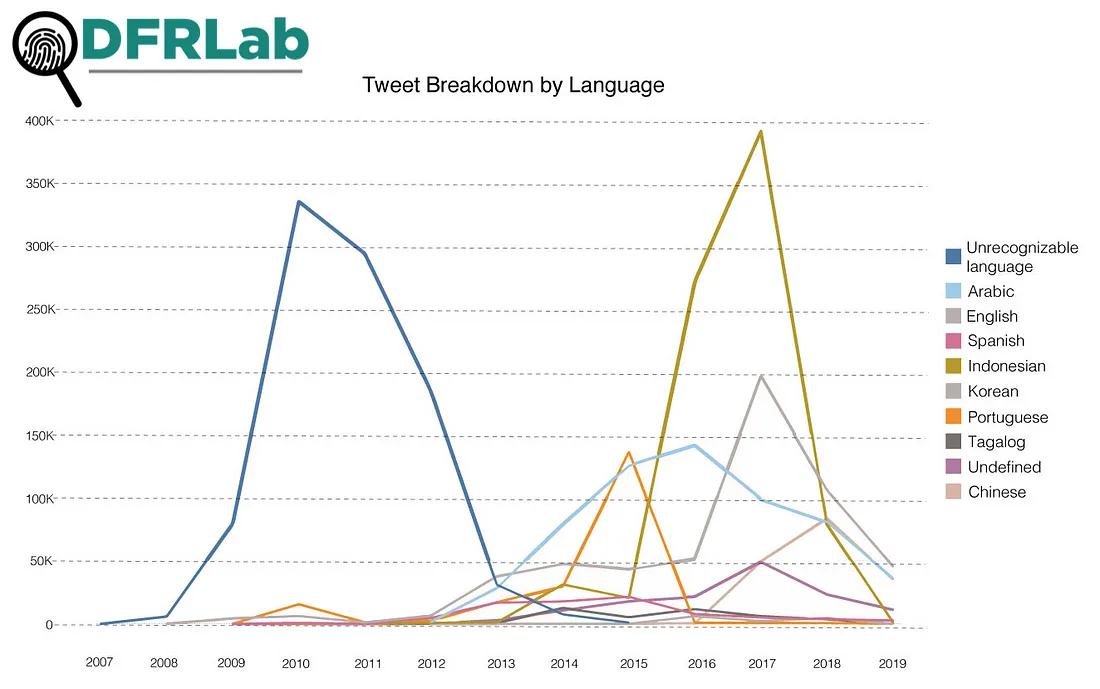

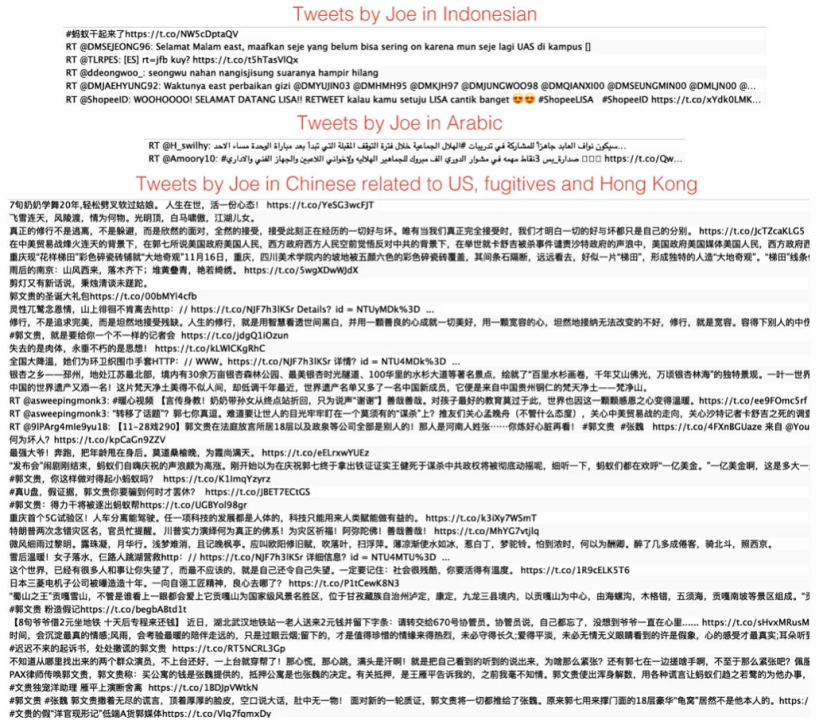

First, the accounts featured an extreme diversity in language use. In addition to Chinese, they tweeted in Indonesian, Arabic, English, Spanish, and several other languages.

The DFRLab previously identified extreme language diversity in tweets among a particular cohort of accounts as characteristic of profit-oriented automated activity. There were two extreme peaks of language use within the set, the first of which comprised tweets in a language the platform could not identify. The second peak, in Indonesian, appeared to be largely comprised of promotional tweets for smartfren.com, a private Indonesian telecom company. It is unclear why these accounts promoted the company.

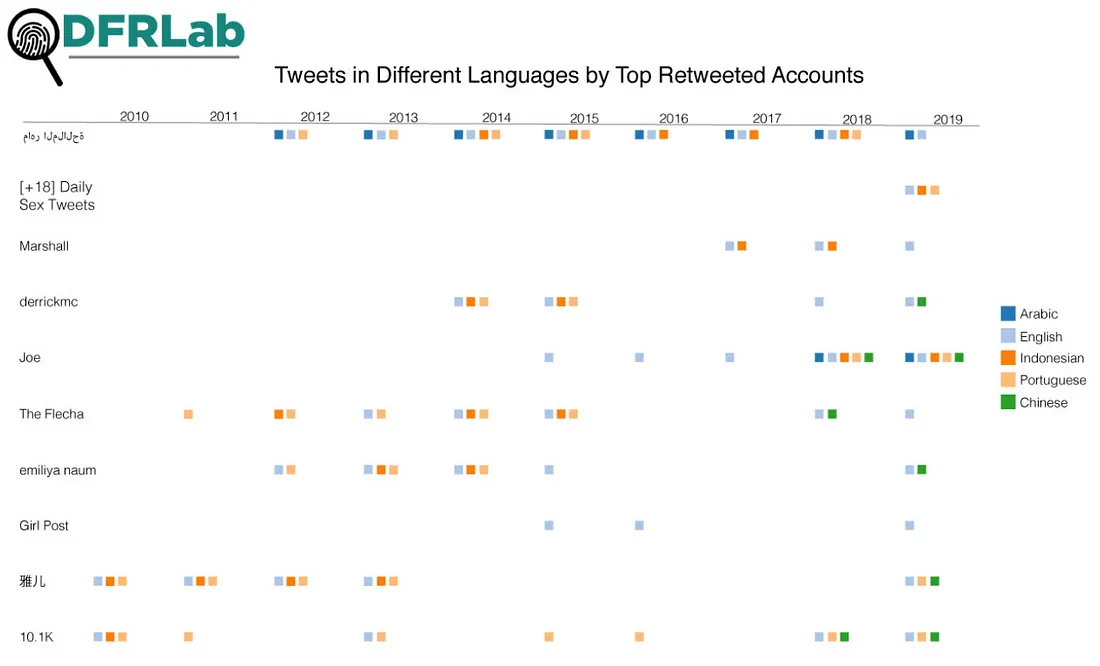

Since 2011, the top retweeted accounts tweeted in multiple languages: Arabic, English, Indonesian, and Portuguese. The first Chinese tweets appeared in late 2018.

This finding suggested that these top accounts had already been involved in multiple, geographically diverse retweet campaigns before being mobilized to target a Chinese-speaking audience.

“Joe,” a top account identified only by its user name in the set, posted a mix of promotional spam tweets in Arabic and Indonesian, in addition to tweets in Chinese focused on the United States, and Hong Kong’s extradition bill. This account may have been a commercial spam bot that was later mobilized to target the Hong Kong protests.

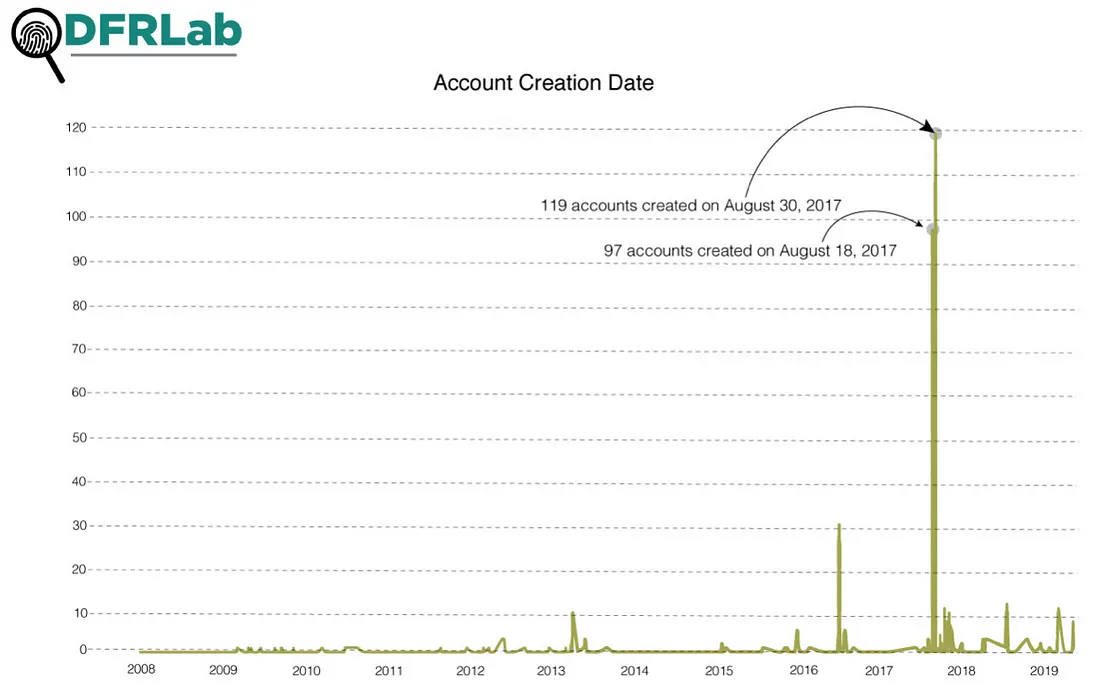

In another indicator of automated activity, many of the accounts were created on the same day. The two most popular account creation dates were August 30, 2017, with 119 accounts created, and August 16, 2017, with 97 accounts created.

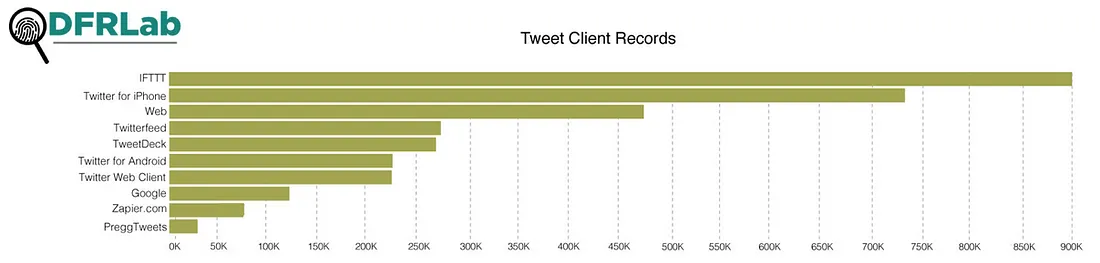

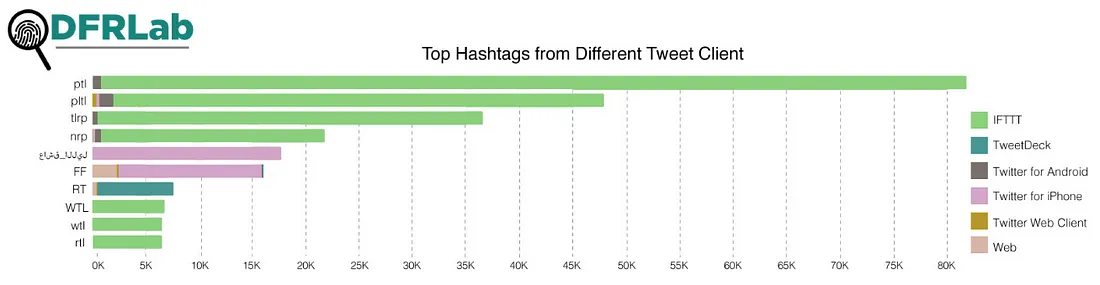

The accounts also relied heavily on third-party automation software. The most popular third-party client was IFTTT, a tool that allows users to automate their posts, including by retweeting particular hashtags.

Much like the top retweeted accounts, the accounts using the IFTTT client posted a significant amount of apolitical content unrelated to the Hong Kong protests. In fact, none of the top 10 hashtags for tweets using IFTTT concerned the protests. One of the most amplified hashtags accounts was “ptl,” short for “praise the lord.” Another top hashtag was in Arabic, while other hashtags seemed to be requests for retweets.

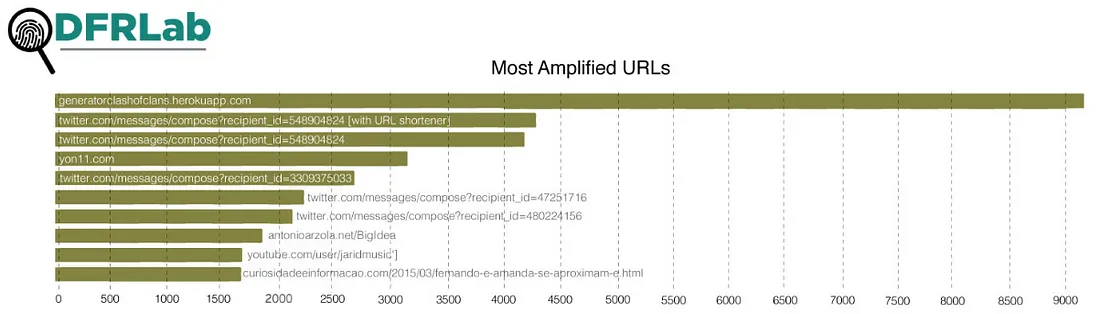

Sometimes, the accounts used inauthentic tactics to amplify promotional links. Many of the accounts for example, used URL shorteners, which primarily serve to mask a specific URL. The most amplified URL was “https://generatorclashofclans.herokuapp.com,” which directs users to an unofficial website for the popular strategy video game, Clash of Clans. The URL was amplified by a single account with about 9,160 tweets and retweets.

The Clash of Clans tweets originated out of a single account that appeared to tag the accounts posting about the Hong Kong protests. Of the account’s more than 70,000 tweets across multiple languages, the DFRLab could not identify any in English or Chinese that directly referenced the protests.

When considered together, these indicators — tweet language diversity, a mix of commercial spam tweets alongside political tweets, identical creation dates, and the use of the same third-party automation client — suggested that these accounts may have belonged to a “retweet farm,” a commercial service that retweets particular posts at high volume. These services often post apolitical promotional tweets but may also be mobilized to post political content.

Applications for Cross-platform Posts

In the analysis, some of the accounts relied on usage of applications and Google Chrome extensions that enabled users to post across platforms in the West and China.

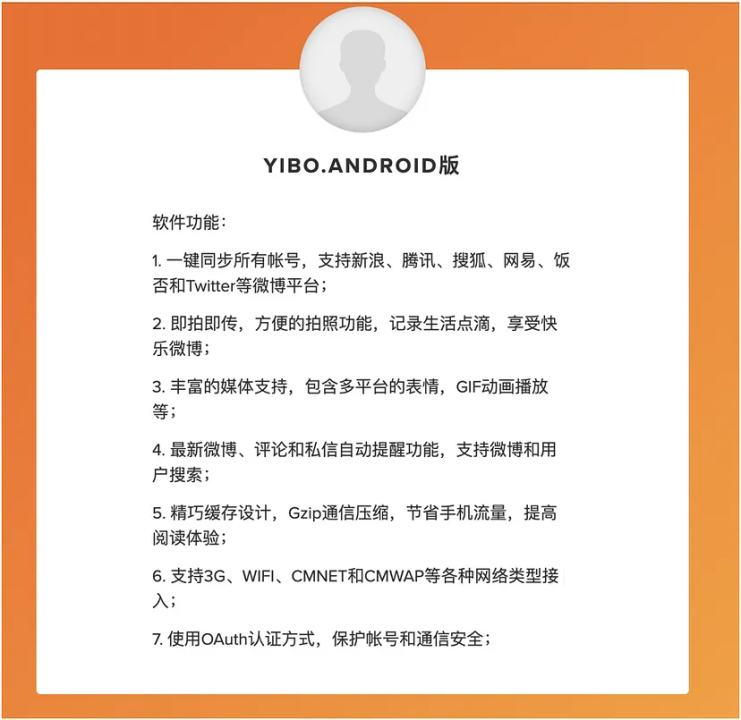

Accounts Tweet Client records show some Chinese applications, one of which was an extension called FaWave. Other accounts used Yibo Android, a Chinese-built app for Android phones that enables cross-platform publishing. The app is not on the Google Play store but is available as an Android Application Package (apk), a file format compatible with Android phones. Similar versions are available on GitHub and related websites.

The accounts employed these cross-platform posting tools to push content in different geographical regions: some, such as Sina Weibo, have a primarily Chinese audience.

A Network Account in Action

While many of the accounts in Twitter’s archive tweeted about the Hong Kong protests, the DFRLab found that a significant portion had also amplified promotional spam content. The network appeared to be inauthentic, given the multiple languages in which it posted, often on the same account and in the same time period. Some of the accounts also started as a means of promoting commercial interests.

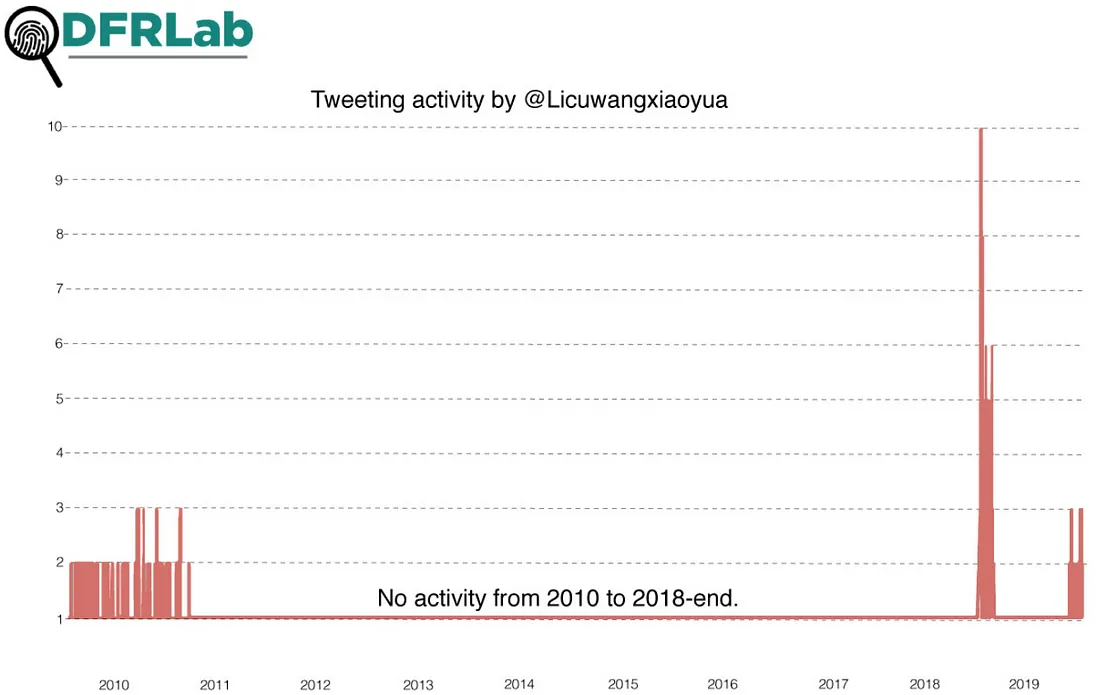

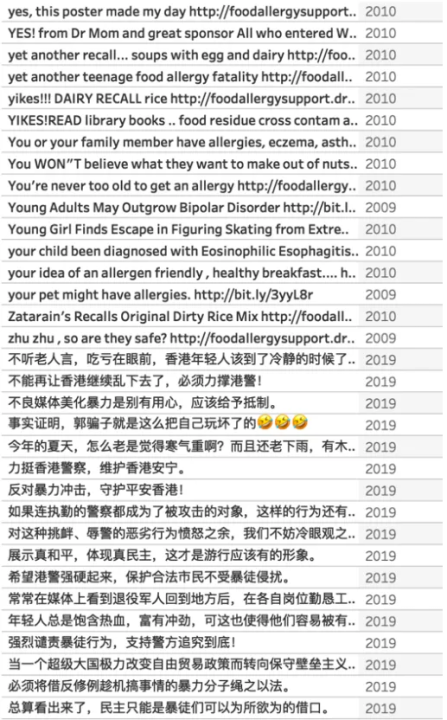

One such account was @Licuwangxiaoyua, which was created in July 2009 and which posted promotions in English into 2010, before falling dormant. Nearly 10 years later, however, it was revived, pivoting from posting commercial content to posting content relating to the protests in Hong Kong.

Ultimately, it appears that the network may have employed a division of labor: some of the accounts were mobilized for political purposes, targeting the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, while others focused on promoting commercial spam-like URLS and content. In some cases, however, the DFRLab found evidence that commercial bots initially focused on tweeting promotional spam in multiple languages had been mobilized and redirected to tweet about Hong Kong.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.