What the TikTok ban and Xiaohongshu’s brief popularity reveal about US-China relations and their tech sectors

Influx of US users to RedNote amid TikTok ban limbo presents propaganda opportunities and censorship challenges for China

What the TikTok ban and Xiaohongshu’s brief popularity reveal about US-China relations and their tech sectors

Share this story

BANNER: An illustration shows the TikTok and RedNote logos with the US flag in the background. (Source: CFOTO/Sipa USA via Reuters)

In mid-January, the US Supreme Court upheld an April 2024 law designed to ban TikTok in the United States unless its parent company, ByteDance, divested ownership. ByteDance was given until January 19 to comply or it would become illegal in the United States to download or support TikTok. The popular app went dark late on January 18, before being restored the next day after an intervention from US President Donald Trump.

The Supreme Court’s ruling followed a years-long legal and political struggle in US courts and in Congress over national security concerns related to the app’s Chinese ownership. Key concerns included the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) potential access to sensitive data collected by the app on American users and potential algorithmic manipulation designed to skew what US users see and hear on the app. After taking office on January 20, President Donald Trump announced an Executive Order (EO) pausing enforcement of the ban for 75 days. As of writing, TikTok is still operational in the United States, but the app remained unavailable for download on Apple’s and Google’s mobile app stores until February 13.

In the lead-up to the Supreme Court ruling and President Trump’s EO, a shift occurred on the platform itself. Hundreds of thousands of TikTok users began migrating to a different China-owned platform, an app known in China as Xiaohongshu, or in English as RedNote. By the time the TikTok ban was set to take effect, Xiaohongshu was the most-downloaded free app in the United States on the Apple app store even though it previously had been little-known outside of China. Xiaohongshu, within two days, reportedly attracted 700,000 new users undeterred by the app’s lack of a serviceable English-language user interface. According to data from Similarweb cited by Reuters, Xiaohongshu’s US user base surged on January 13, 2025, when it gained nearly 3 million US users. As more US users began to use the platform, their interactions with their Chinese counterparts began to go viral. Trends that gained popular attention in US and Chinese media included Americans asking Chinese users to “roast” them, Americans joking about connecting with their “Chinese spy,” and Chinese netizens introducing Americans to Chinese internet culture by demanding “cat taxes.” At the same time, the app scrambled to recruit and hire enough English-speaking content moderators to make sure it met the stringent censorship requirements of the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), the country’s internet “superregulator.”

In this piece, we contextualize the exodus of what have been dubbed the “TikTok refugees” to Xiaohongshu by providing context about the app, about China’s social media ecosystem, and about the differences between Xiaohongshu and TikTok. Next, we dig into narrative trends on Xiaohongshu about the TikTok ban and the trends surrounding a host of hashtags about the #TikTokRefugees. We pay particular attention to the narratives promoted by Chinese state media sources, finding that overall, the CCP has used the opportunity to criticize the United States and portray China as innovative, welcoming, and non-threatening.

What is Xiaohongshu?

Xiaohongshu is a lifestyle social media app based in China. Founded in 2013, it initially provided international shopping guides for Chinese users. The app experienced some serious obstacles, such as a temporary removal from the Chinese Android app store in 2019 because of PRC government concerns about the quality of goods sold on the platform and a lack of censorship of what Beijing considered inappropriate and politically sensitive content. But by 2020, Xiaohongshu had hit its stride and experienced slow but steady growth.

Compared to other Chinese apps, Xiaohongshu’s appeal is based largely on its community search features. Xiaohongshu’s users tend to use the app as a search engine, seeking help on everything from cooking tips to naming their new pet cat. According to the company’s 2024 mid-year search habits report, around 50 percent of its more than 300 million monthly active users (MAUs) belonged to Gen Z. Although the app has expanded its reach to more male users, the majority of the app’s users are women who live in large cities (in contrast to Kuaishou, a Chinese app known to be popular among China’s rural population). Xiaohongshu has fewer MAUs than other Chinese apps, including WeChat (1.16 billion), Douyin (766.5 million), and Kuaishou (497.5 million). Rednote is the international version of Xiaohongshu. Representatives from the company have claimed that the two apps are independent platforms and that the user account systems are not connected. TechBuzz China reported that US- and China-based users were able to see each other’s content and comments as of January 25, 2025. Moreover, when one enters “Xiaohongshu” in the search function of both the US-based Apple and Android app stores, “Rednote” is the name of the app that appears in the search results.

As a China-based, domestically focused app, Xiaohongshu is a very different app from TikTok, having a separate user base, different terms of service, distinct content management principles, and its own privacy policies. Unlike TikTok, which has multiple user interfaces in different languages, Xiaohongshu until recently had a single user interface in Mandarin (though it added a translation feature in January 2025 as more English users flocked to the app).

TikTok, on the other hand, is the international version of the Chinese app Douyin, which is only accessible in the Chinese market and is unavailable for US users to download. TikTok was launched internationally in 2017. Its parent company, ByteDance, acquired the short-video app Musical.ly in 2017 and merged the acquisition with its existing TikTok platform in August 2018. TikTok went on to become the fastest-growing app in the US market from 2021 to 2023. In 2024, 17 percent of all American adults said they received their news from TikTok.

Considering the apps’ differences, we set out to understand how Xiaohongshu came to be the replacement app of choice for TikTok, at least for a while. The DFRLab and Two Six Technologies conducted an analysis of social media trends on Xiaohongshu between January 12-18, 2025, the one-week period which marked the height of US user migration to Xiaohongshu.

We did not detect evidence of a coordinated inauthentic campaign using bot accounts to encourage TikTok users to move to Xiaohongshu. Rather, the switch to Xiaohongshu appeared organic for several reasons. The first reason that users may have flocked to Xiaohongshu of their own accord is simply that downloading the app may have been easier for US users than any other Chinese option. Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, is largely unavailable in US app stores for download, but Xiaohongshu has been available since 2014. True to its origins as an international shopping app, the app was made available on international app stores so that overseas Chinese could download it abroad. The app has also been popular with shoppers that are known as daigou, Chinese entrepreneurs who go abroad to purchase items that are rare or hard to find in China to sell upon their return. Further, creating an account on Xiaohongshu does not require a Chinese phone number. In contrast, apps like Weibo and Douyin require real name registration connected to a China-based mobile phone number.

Second, Xiaohongshu’s newfound popularity in the US could reflect the natural continuation of an existing trend. According to research by the market intelligence tool AppMagic, shared via Statista, Xiaohongshu hovered between 150,000 and 275,000 downloads in the US per quarter from Q2 of 2022 until the second half of 2024, when downloads rose to more than 350,000 (Q3) and 500,000 (Q4). Various sources have given differing figures on the number of downloads of the Xiaohongshu app by US users in Q1 of 2025, though the sources tend to agree that early 2025 witnessed a growth in interest in the app among US users. Estimates of the number of downloads as of January 16, 2025, range from 700,000 by AppMagic via Statista to up to around 3 million by Reuters citing Similarweb. This data suggests that Xiaohongshu’s growth didn’t suddenly appear out of nowhere in January 2025, but rather the app saw steady upward growth throughout the six months before TikTok’s ban was set to take effect on January 19.

Third, the choice to shift to Xiaohongshu was a deliberate move by at least some US users to protest US regulatory action on TikTok. A subset of US users explicitly said that they chose the Chinese app as a form of political protest. This tactic seeks to undermine a key argument in the rationale for the TikTok ban in the US–the concerns over China’s access to Americans’ personal data. These politically motivated users appeared to frame their move to Xiaohongshu as an effort to thwart US regulators from exerting control. The tactic was used despite the risks associated with adopting another China-owned app that stores its data in China and that arguably could provide much more unfettered access to user data than TikTok.

Narratives on Xiaohonghsu: #TikTokRefugees

In the days that followed the brief enactment of the TikTok ban, both TikTok and Xiaohongshu were rife with narratives related to the ban, discussions about the presence of Americans on Xiaohongshu, and conversations about the differences in lifestyle in the United States and China. Below we dive into the “TikTok refugee” narratives that we observed Chinese state media accounts promoting.

When the TikTok ban briefly went into effect, The New York Times reported that almost 33 million posts with over 2.3 billion views were posted on RedNote using the #tiktokrefugee hashtag. Using Newrank, a Chinese platform for social media analytics, we examined the most-viewed hashtags that were created from January 11-19, 2025, on Xiaohongshu. The top hashtags were mostly variations of spellings of the most popular hashtag, #tiktokrefugee, which served as a general-purpose hashtag referring to the migration to Xiaohongshu. Regarding more specific hashtags, “猫税” (cat tax) and “大声安利中华美食” (loudly promoting Chinese cuisine) were the most viewed and had the most participating users. The 100th-ranked hashtag was “中美大对账” (the grand audit of China and America), referring to the widespread practice on the app of comparing US and Chinese living standards (on which China came out on top in the opinion of many users). Despite these narratives emerging, we observed that most of the 150 top hashtags during this period contained apolitical posts sharing lifestyle content and exchanging cultural information.

In Figure 1 below, we graphed the prevalence of the hashtag “tiktokrefugee,” the most- viewed hashtag in the sample period. The amount of engagement peaked on January 15 and then declined slowly. When President Trump signed the January 20 EO postponing the TikTok ban, the engagement metrics for this hashtag continued to decline, though much of the decline had already occurred. By the end of January, the amount of engagement with the hashtag was less than 0.2 percent of the peak.

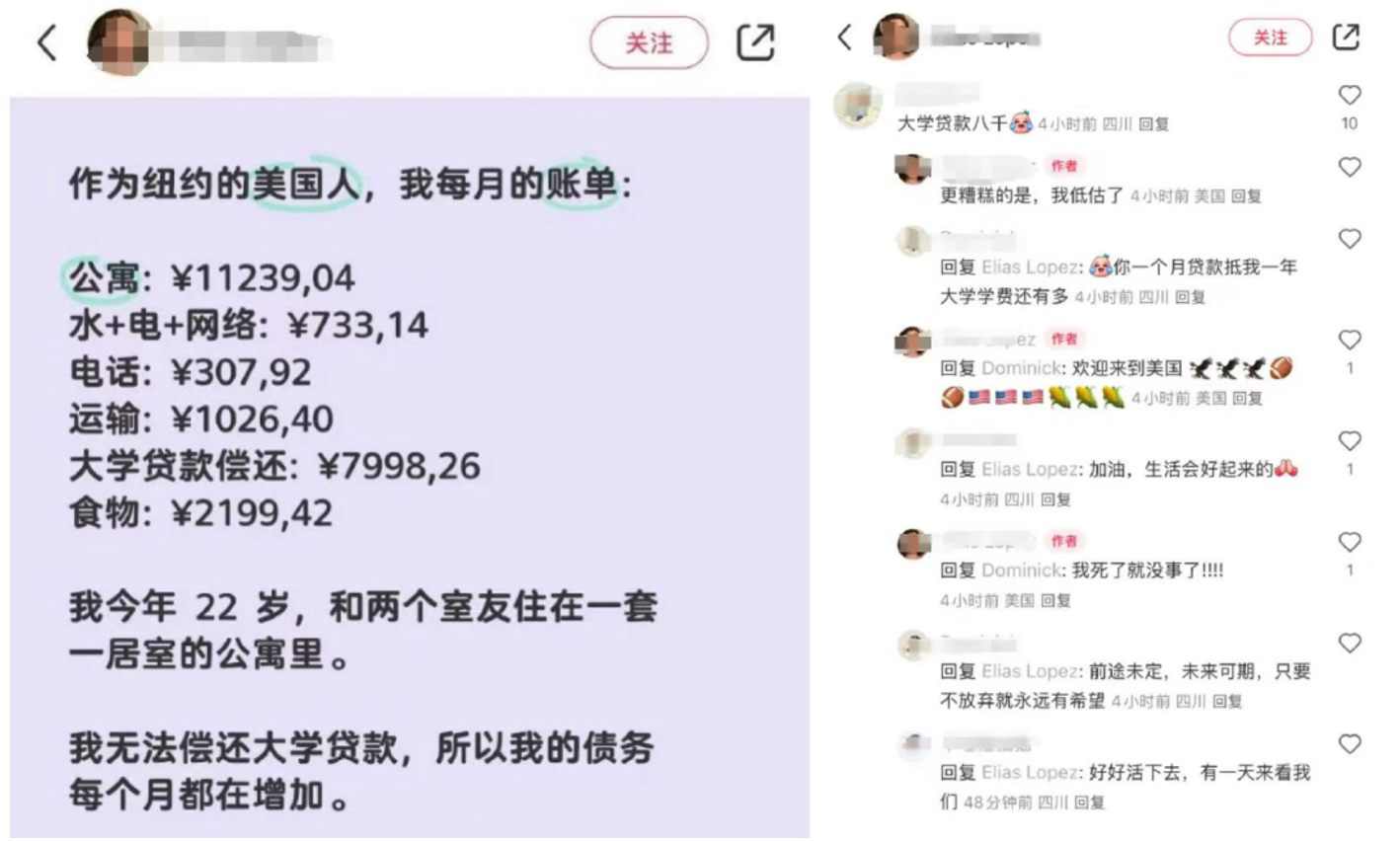

As Chinese and American users mingled on Xiaohongshu, Chinese state media began to seize opportunities to amplify at least three narratives that reflected unfavorably on US prosperity and the US government’s efforts to regulate Chinese tech platforms. First, Chinese propagandists promoted claims that many US netizens had low living standards and few economic opportunities. The Chinese state-sponsored news channel CGTN, for instance, cited multiple US users on Xiaohongshu who raised concerns about the affordability of housing, education, and healthcare. Yet the article glossed over concerns among Chinese netizens about China’s well-documented property market slump and other economic struggles. At least one official PRC propaganda account on Xiaohongshu tried to make the case that discussions about the living standards of Americans on the app undercut perceptions that China’s economy was struggling. For example, a Xiaohongshu account managed by the Zhejiang Propaganda Department wrote, “Many American netizens also found that the argument claimed by their country’s media that ‘China has been in dire straits for a long time’ is completely inconsistent with the reality.”

Narratives related to these comparisons of living standards spread to other Chinese platforms. On Weibo, the hashtag “After Chinese and American netizens compared notes on living standards, some people were devastated” (中美网友对账后有些人天塌了) reached number two on the leaderboard on January 18, with the Chinese state media outlet Beijing Daily moderating its Weibo hashtag landing page, controlling which related posts were promoted or censored there. The Chinese video platform Bilibili has about ten videos with over one million views each uploaded between mid- to late-January about China winning the comparison of living costs. These videos were mostly created by pro-China independent media, and they included hosts from Jinan Television and the nationalist media outlet Guancha.

Second, Chinese state media spread a narrative claiming the US government deceived Americans into viewing friendly Chinese people as a threat. The Global Times, for instance, accused US officials of disparaging China and enveloping Americans in a fear-based “information cocoon” that Americans on Xiaohongshu supposedly shed when friendly Chinese netizens greeted them upon their arrival on the app. The Xinhua News Agency reposted a video on Xiaohongshu attributed to an American user who dramatized his “escape” from the TikTok ban to reach the “real world” in a digital chase set to the Star Wars theme song. PRC state media also promoted the narrative that Xiaohongshu was a “global village,” a non-threatening, welcoming, and harmonious online space for users from all around the world.

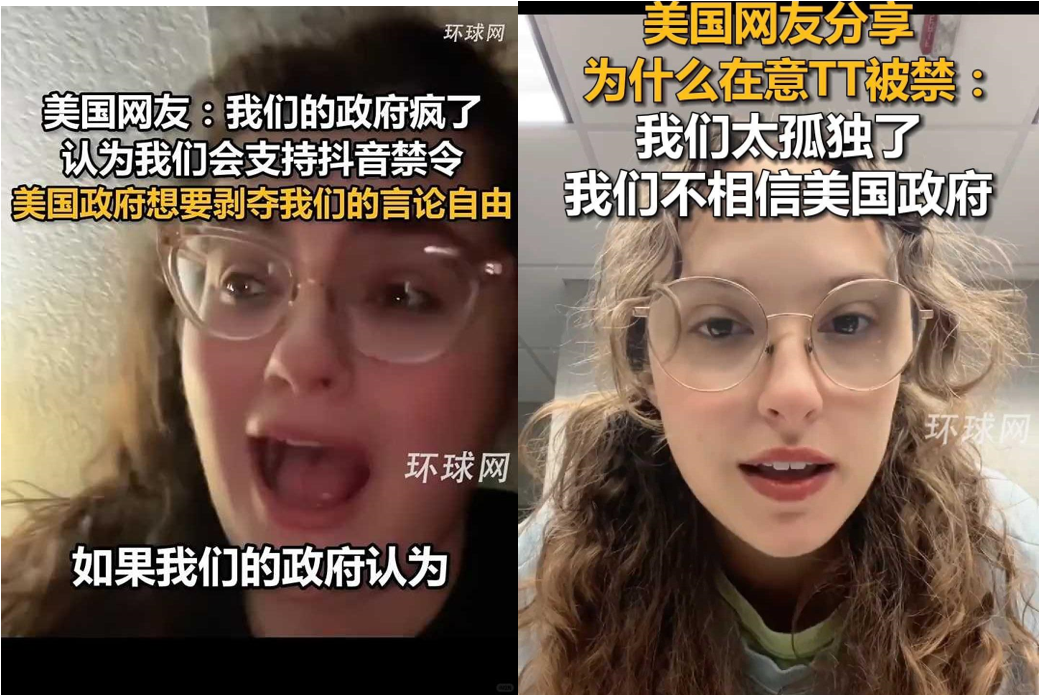

Third, Chinese state media sought to portray the postponed TikTok ban as an erosion of Americans’ freedom of speech and a gambit to stifle more innovative Chinese tech platforms. However, Chinese propaganda promoting this narrative neglected to mention China’s onerous censorship requirements and data storage regulations that have led several US tech platforms to leave or forgo the China market. A China Daily article claimed that the exodus to Xiaohongshu was “an act of protest against the US government’s decision,” adding, “many believe this [switch to Xiaohongshu] is in defense of freedom of speech.” In another Xiaohongshu post, Xinhua shared a video from a US user saying that many US netizens would rather learn Mandarin and jump to Xiaohongshu than spend their time on US social media platforms. PRC state media also reposted other videos of Americans who protested the TikTok ban claiming that the law was taking away their freedom of speech or saying that they didn’t trust the US government.

Conclusion

The impending TikTok ban led millions of US users to migrate to Xiaohongshu, at least temporarily, encouraging cross-cultural dialogue but also creating openings for Chinese state media to push narratives that depict China as innovative and welcoming while criticizing the US for its living standards and its regulatory approach to Chinese apps like TikTok.

The CCP must weigh a fundamental tradeoff when deciding how to react through public messaging and other tools to US regulatory efforts involving China-based tech companies. On the one hand, the influx of US users on Xiaohongshu has been a propaganda boon for China in many ways, domestically and internationally. In fact, Dong Yu, a former CCP official who worked in economic affairs, described it as a major soft power opportunity, stating, “Everyone must pay close attention to the influx of TikTok users into Xiaohongshu. This is a truly historic opportunity with immeasurable value. If utilized properly, it could break [China’s] longstanding passive position in the international public opinion arena.”

The public debate surrounding the TikTok ban has helped dull the urgency, at least among some netizens, of scrutinizing the CCP’s use of coercion, its censorship apparatus, and its treatment of Chinese citizens. Indeed, US news sites have featured anecdotal reports of American users expressing skepticism, after chatting with Chinese users, of US policymakers’ claims about China’s autocratic activities, including claims about the “social credit system” (such as perceptions that the Chinese government employs an all-seeing, algorithm-powered scoring system to grade individuals’ and businesses’ trustworthiness). Public reactions to the ban have also fueled questions about how the US government regulates US-based and foreign social media platforms and other tech companies. The ban has further prompted questions from users about how well US officials have delivered on improving living standards in recent years.

On the app itself, Chinese users have heard tales of Americans’ economic hardships, including limited healthcare access and higher living costs, and they have encountered criticisms of US-based tech companies. To some degree, Chinese propagandists have been able to capitalize on US users’ discontent about the TikTok ban to curate a handpicked, self-serving narrative that US prosperity and values are on the retreat while Chinese prosperity and values are on the rise, though it is too early to say whether the narrative will stick. This is happening at a critical moment when China has been facing pressure domestically, with rising violence, a flagging economy, and repeatedly falling birth rates.

On the other hand, the presence of so many English speakers on Xiaohongshu presents serious challenges for Chinese censors bent on maintaining information control, long a central pillar in the CCP’s concept of national security. The app is reportedly short on censors with the English-language capabilities to police foreign users. There have been many reports, for example, of Americans trying to push censors’ buttons by talking about sensitive topics like the Tiananmen Square crackdown and Xinjiang. Even users who have not raised sensitive topics have found themselves running afoul of censors. China expends extensive resources to suppress discussion of certain topics on the Chinese internet, and unexpected cultural interactions with foreigners on Xiaohongshu could threaten or at least complicate that work. Censorship of foreigners is more likely to attract global attention, detracting from the rosy propaganda that bills China as a great travel destination and a prosperous country. Beijing’s efforts to censor US netizens’ discussion of tragedies like the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown and human rights violations like those against Uyghurs in Xinjiang risk bringing renewed global attention to these issues. On the other hand, failing to censor or cordon off US users could expose netizens in China to alternative sources of information about life in and beyond China that challenge the assumptions and prevailing narratives of CCP-backed propaganda.

For now, CCP officials seem to be taking limited precautions to keep censors’ grip on Xiaohongshu strong even as they buy time to see how the TikTok ban plays out and whether foreign interest in Xiaohongshu is sustained. The tech news site The Information reported that CCP officials told Xiaohongshu it “needs to ensure China-based users can’t see posts from US users.” Meanwhile, Voice of America noted that Chinese netizens on Xiaohongshu have said that the prevalence of foreigners on the site has noticeably declined. Another factor is the ultimate fate of TikTok in the US between now and the early April deadline presented in President Trump’s January 20 EO. In the meantime, TechCrunch noted that the number of US users on Xiaohongshu dropped sharply after TikTok came back online for existing US users after a one-day outage.

On the US side, the Xiaohongshu migration highlights some long-simmering tensions concerning the US’s regulation of technology and social media platforms. The US faces its own tradeoffs with regards to Xiaohongshu. Depending on the final status of the TikTok ban and the staying power of US users on Xiaohongshu, the US government may see fit to try to ban Xiaohongshu from the US market on similar grounds as the TikTok ban, an option that an unnamed US official told CBS News could be on the table. There is no doubt about whether the CCP could access US user data through Xiaohongshu, as the app likely stores all of its data on servers located in China.

Beyond Tiktok and Xiaohongshu, however, is the issue of a broader lack of protections for Americans’ personal data. There is a lack of transparency or algorithmic requirements for social media companies that operate in the US writ large. Users have become cynical about US protections of their data, and some may see little downside to protesting US actions on TikTok by flocking to an app that could expose their data to a broader, more consequential, and more direct exfiltration by the CCP. Instead of a whack-a-mole approach, the US should look at the information environment more holistically and enact protections for Americans that apply to a host of apps, including China-based ones. If these issues continue to be overlooked, there will be future Xiaohongshu moments – and the US will be no closer to a solution.

Ryan DeVries is a senior China subject matter expert at Two Six Technologies.

Two Six Technologies is owned by the Carlyle Group.

Cite this case study:

Kenton Thibaut and Ryan DeVries, “What the TikTok ban and Xiaohongshu’s brief popularity reveal about US-China relations and their tech sectors,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) and Two Six Technologies, February 24, 2025, https://dfrlab.org/2025/02/24/tiktok-xiaohongshu-rednote-us-china/.