How social media shaped the 2025 Canadian election

Platform enforcement gaps, AI-generated spam, and foreign interference concerns converged during high-stakes political contest.

How social media shaped the 2025 Canadian election

Share this story

Banner: Canada’s Prime Minister Mark Carney speaks at the Liberal Party election night headquarters in Ottawa, Ontario. (REUTERS/Jennifer Gauthier)

Liberal Party leader Mark Carney defeated Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre on April 28 to become Canada’s Prime Minister in an election where sovereignty unexpectedly took center stage. The campaign unfolded amid persistent comments from U.S. President Donald Trump that Canada should become America’s “51st State”—remarks which all candidates firmly rejected while positioning themselves as best equipped to manage Canada-U.S. relations. This unusual diplomatic tension, coupled with a severe domestic affordability crisis, drove record voter turnout and shaped campaign messaging through election day, when Carney opened his victory speech with a direct appeal: “Who’s ready to stand up for Canada with me?”

During the 2025 snap election, candidates campaigned in Canada’s cities and towns—but also across a uniquely challenging information environment. The ongoing news blackout on Meta platforms created significant gaps in the media ecosystem, while AI-generated content and coordinated messaging campaigns flourished online. This analysis examines these digital dynamics—from domestic partisan networks to foreign actors’ activities—and what they reveal about the evolving challenges to electoral integrity. By understanding how information circulated during Canada’s election, we gain critical insights into the vulnerabilities facing democracies worldwide.

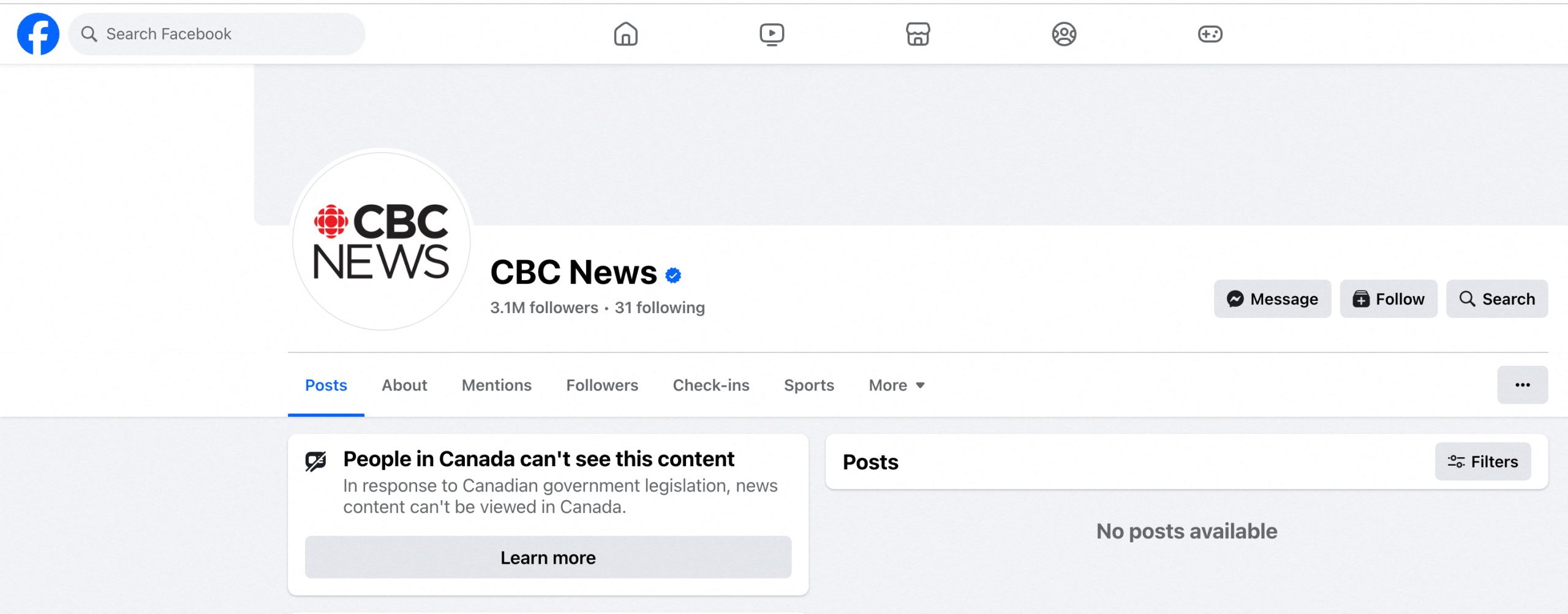

Systemic effects of Meta’s ‘news ban’

One distinguishing feature of Canada’s information ecosystem has been Meta’s decision to block news content for Canadian users in response to the Online News Act (Bill C-18), which passed in June 2023. The bill sought financial compensation from Meta and Google for the sharing of news media on their platforms in order to sustain a journalism and digital media sector badly affected by dwindling ad revenue. Canada’s bill followed a similar effort from Australian legislators, who, after some negotiation and resistance (including an Australian news blackout on Meta platforms), reached deals with the platforms for compensation. In Canada’s case, however, Meta has made no such concessions, and the ban remains in effect.

The information vacuum left by this decision has enabled hyper-partisan content to dominate in the absence of balanced media coverage. A report from the Media Ecosystem Observatory found that Canadians are seeing significantly less news online, estimating a drop of approximately 11 million daily views across Instagram and Facebook. Exacerbating the issue was Meta’s January 2025 decision to end its fact-checking programs, which helped limit the spread of false or misleading information; safeguards that are even more necessary in the face of AI-enabled fraud and deception.

Meta did not discount the Canadian election entirely. In March, the company announced several measures to assist Canadian voters, including partnering with Elections Canada to deliver reliable top-of-feed voting reminders and a recommitment to political ad transparency.

Ultimately, however, Canadians were unable to view basic news reporting on Meta platforms, while election-related hoaxes and falsehoods remained freely accessible. Not only was this dangerous for Canada—it also sets a chilling precedent for other democracies who are considering their regulatory measures against the social media giants.

AI-enabled deception already hard to track; platforms make it harder

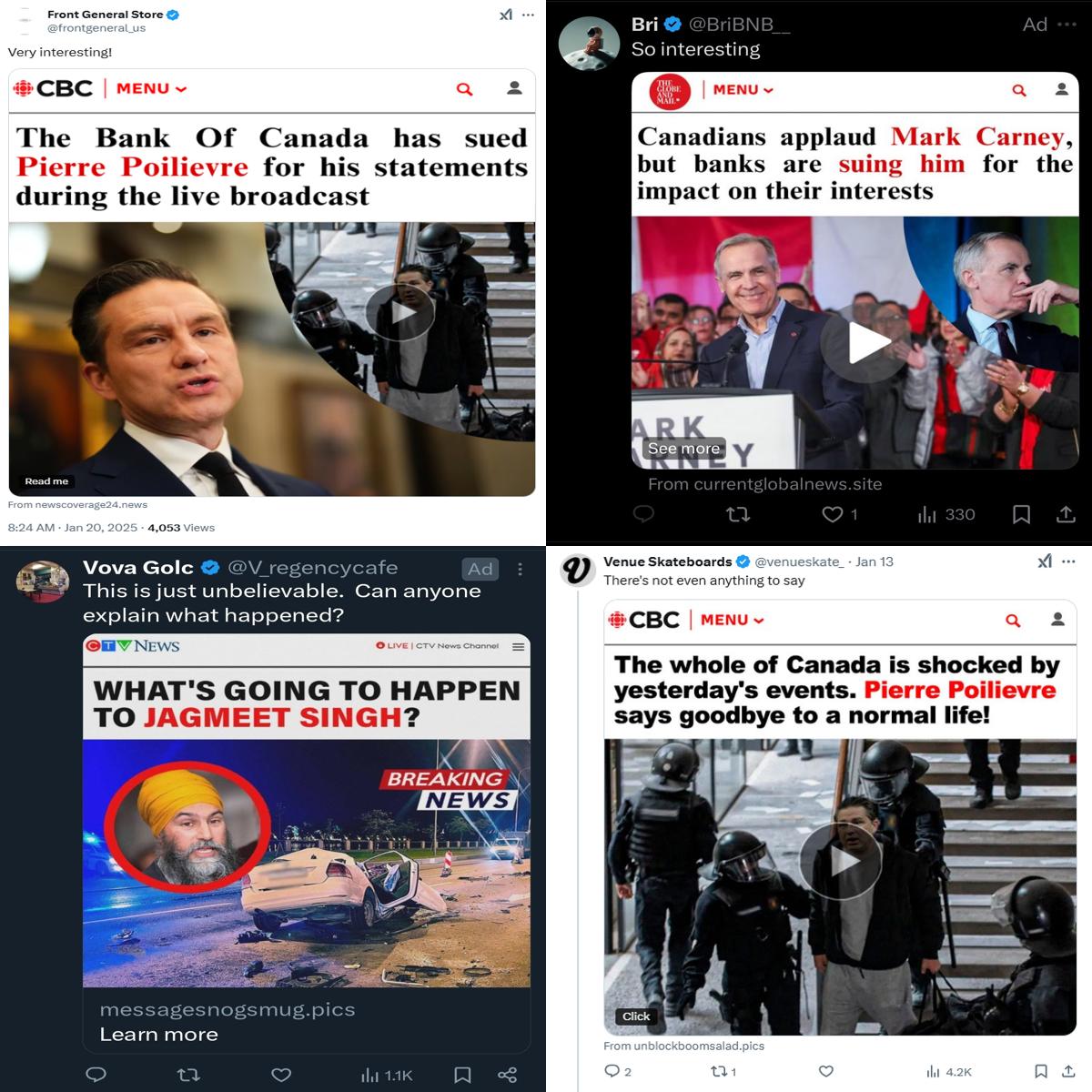

Canada’s election was targeted by at least one major cross-platform campaign that used AI tools to mislead Canadians. The campaign was initially identified on X, where it combined sensationalist headlines and facsimiles of real Canadian news pages in order to lure users into cryptocurrency scams. In one case, for instance, Pierre Poilievre was quoted in a fake interview as swearing by something called “Quantum AI”—a fraudulent investment scheme that has previously targeted Australia and the United Kingdom.

As the election period developed, so did the scale and political crossover of the network. It proliferated across Canadian Facebook, using AI-generated images and videos to grab user attention. The Canadian Digital Media Research Network (CDMRN), of which DFRLab is a part, identified seven deepfakes of Mark Carney, mimicking CBC or CTV news interviews and directing users to scam websites. Deepfake images impersonating credible media outlets—accompanied by salacious headlines—variously portrayed Carney, Poilevre, or the NDP leader Jagmeet Singh as somehow wounded or under arrest.

While there is no confirmation that the campaign was operated by Russia, CBC reported that the operation used a Russian name server, and, until October, had used a Moscow-area hosting server. A thorough examination of the operation’s activity by the CDMRN found that the campaign’s content was generally pro-Liberal and moderately impactful, with 25 percent of surveyed Canadians having been exposed to these fraudulent news organizations. Of that group, 59 percent said they immediately recognized the content as fake. Unfortunately, that still left some exposed users who may have accepted false or misleading information as fact.

Although the campaign relied on social media advertising in order to grow its audience, the ads transparency measures of these platforms proved little help in unraveling it. X’s ads repository was entirely unreliable as an investigative aid. Meta’s Content Library was only a little better. Because nearly all of these election-related ads were classified as “non-political,” they did not readily populate in the Content Library. Canada-based investigators regularly identified violative content by way of their personal Facebook feeds, with no way to record them or determine who was behind them.

Canada Proud and Meta’s hyper-partisan news carve-out

The right-wing Canada Proud network was a potent political force during Canada’s election cycle. It boasts over 1.4 million followers across various mainstream platforms, with its largest audience on Facebook. Between January and mid-March, Canada Proud spent heavily on Facebook ads, running “more than 1,400 Facebook and Instagram ads…at a cost of between $208,000 and $278,684 CAD,” according to The Logic’s review of the Meta Ad Library. All of these ads targeted Carney. Because of Canada’s strict regulations on third-party election advertising, Canada Proud ceased its paid advertising efforts once the election was called on March 24.

However, this hardly meant that Canada Proud ceased its election-related efforts. Misleading narratives primed by Canada Proud in the pre-election period carried on by way of viral screenshots and commentary. Because Canada Proud was not a formal news organization, it was able to freely disseminate this content even as fact-checks and neutral reporting were suppressed by Meta’s news ban.

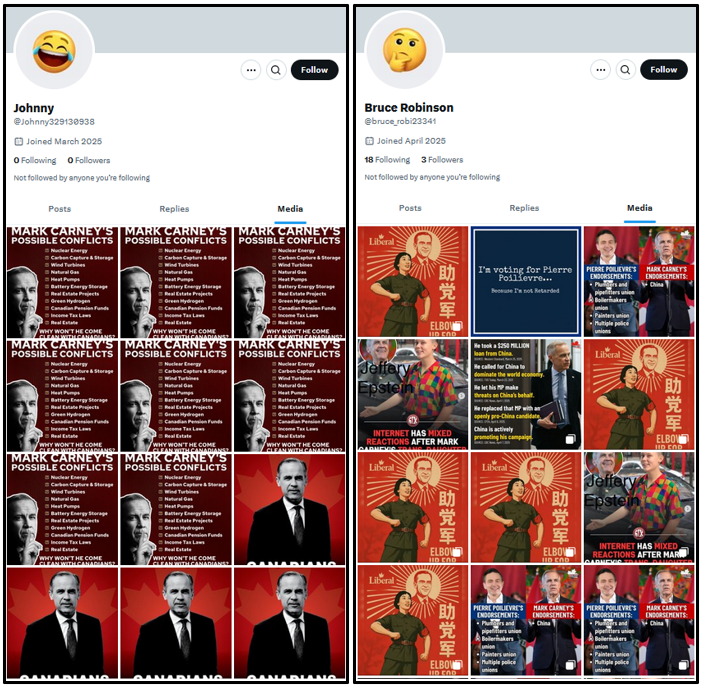

Bots on X: loud and consistently right-wing

As identified by the DFRLab and in a separate Financial Times investigation, bots were active in force on X during the election period, most often championing right-wing causes.

The DFRLab discovered a series of X accounts exhibiting the tell-tale signs of inauthenticity, denoted by a high number of reposts and replies, rapid response times, irregular posting behavior, and the lexical complexity of replies. These accounts boosted politically charged spam and misleading narratives, roughly 80 percent of which were directed at the Liberal Party and its leadership. In some cases, these bot-like accounts amplified graphics first shared by Canada Proud. A few of the identified accounts were restricted by X for “unusual activity” prior to April 28. Most, however, were not.

This bot network heavily promoted the misleading, but prevalent, narrative that sought to tie Carney to Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell. The narrative gained momentum in January, when group photos of Carney and Maxwell leaked showing them both in attendance at a 2013 music festival, at a time when Carney was governor of the Bank of England. These photos were soon joined by a flood of AI-generated fabrications that included Carney and Epstein swimming in a pool, and Carney and Maxwell dining in an intimate setting. In turn, this series of fake or decontextualized images became ammunition for clusters of automated anti-Carney accounts.

Persistent shadow of foreign interference

While domestic actors appear to have dominated Canada’s information landscape during the snap election, the Canadian government and civil society remained keenly aware of the threat of foreign interference. Indeed, in January 2025, Canada’s Public Inquiry into Foreign Interference in Federal Electoral Processes and Democratic Institutions released its final report, referring to disinformation as the “single biggest threat” to Canadian democracy. It named China, India, and Russia as key adversaries with both the capability and motivation to conduct interference campaigns against Canada.

Foreign interference is a developing, but not new, challenge for Canada. The public inquiry found that China attempted to meddle in Canada’s 2019 and 2021 elections, albeit without significant effect, concluding that its activity did not shape election outcomes. Similarly, as documented by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), a campaign linked to India reportedly interfered in the 2022 Conservative Party leadership race to help elect Pierre Poilievre, though no evidence suggests Poilievre or his party were aware of these efforts.

During the 35-day election cycle of 2025, publicly identified foreign interference operations remained relatively limited—possibly due to the shortened campaign period, but potentially also reflecting challenges in detection. Among the interference attempts that were identified, China was the most prominent actor.

China, Youli-Youmian, and Domestic Politicization

In a notable first, Canada’s Security and Intelligence Threats to Elections (SITE) Task Force publicly disclosed foreign interference during an active election period, highlighting the activity of WeChat account Youli-Youmian. According to the Canadian government, this influential news account is linked to the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission (CPLAC) and represents China’s most popular news source on the platform.

SITE observed surges of coordinated inauthentic behavior and manipulated amplification tactics seeking to influence Canadian-Chinese communities with both positive and negative narratives targeting Carney. It is a known tactic of Chinese information operations to spread contrasting narratives in an attempt to flood the information space, with similar activity documented during the most recent U.S. election.

However, further examination of Youli-Youmian’s public activity by CDMRN investigators found that Canada was not a central focus; rather, it was one of several countries referenced in broader international reporting. In assessing the news channel’s activity in relation to its other posting activity, CDMRN found posts about Canada were fewer and less engaged with than coverage of other countries like the United States or Ukraine.

In any case, the disclosure gained traction and was soon co-opted by the Conservative Party for its own ends. Reelected Conservative MP Michael Chong, who was previously targeted by Youli-Youmian, and reelected Conservative MP Michael Cooper, both suggested that China was spreading pro-Liberal Party content to help elect Carney. This narrative gained momentum as Poilevre had already sought to connect Carney with China, attempting to portray Carney as being “compromised by the authoritarian regime in Beijing.”

Another SITE report identified Joe Tay, a defeated Conservative candidate, as the target of “transnational foreign repression.” In December 2024, Tay was subject to a $178,600 CAD ($128,900 USD) bounty from the Hong Kong Police in connection with his YouTube channel, HongKongerStation, which advocated for democracy while opposing the Chinese government’s activities in Hong Kong. The online campaign targeted Tay with a mock wanted poster and disparaging headlines and comments. These claims spread across Facebook, WeChat, TikTok, RedNote, and Douyin, the Chinese mirror of TikTok. At the time of publication, it was too early to judge whether this defamatory campaign had any impact on Tay’s election bid.

A glimpse of challenges to come

The 2025 Canadian election saw the convergence of geopolitical tensions, opportunistic campaigning, and serious platform vulnerabilities. Meta’s news blackout created an information vacuum readily filled by hyper-partisan content. Platform data access limitations hampered investigators’ ability to track influence operations in real-time. And foreign interference proved a persistent concern for Canadian officials charged with securing the election, even as it became a periodically contentious campaign issue.

This election cycle also underscores the need for a coordinated and comprehensive approach to protecting democratic processes from digital threats. Such a strategy must integrate technical detection, digital literacy programs, and regulatory frameworks that account for the strengths and weaknesses of platform governance. And it must protect not only election integrity, but also the principles of free and open expression. The goal is not just safety, but a safe democracy.

The DFRLab is a member of the Canadian Digital Media Research Network.

Cite this case study:

Layla Mashkoor, “How social media shaped the 2025 Canadian election,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), April 29th, 2025, https://dfrlab.org/2025/04/29/how-social-media-shaped-the-2025-canadian-election/.