#ElectionWatch: Fraud and Suppression Claims in United States

Plenty of narratives and less evidence of election cheating ahead of the midterms

#ElectionWatch: Fraud and Suppression Claims in United States

Plenty of narratives and less evidence of election cheating ahead of the midterms

Supporters of the Republican party, especially President Trump, raised online concerns of massive voter fraud ahead of the midterm elections in the United States. Meanwhile, supporters of the Democratic party raised concerns of voter suppression, and partisans on both sides made exaggerated and baseless claims.

Americans go to the polls on November 6 to elect 435 members of the House, 35 Senators and 39 state and territorial governors. The campaign season has been hugely polarizing, with pundits predicting that the United States will emerge even less united than before.

No evidence has yet come to light to substantiate the claims of massive voter fraud. There is evidence in some states, notably Georgia and North Dakota, to suggest deliberate voter suppression. On both sides, however, partisan users have gone beyond the evidence to make exaggerated or baseless claims.

In such a polarized atmosphere, any claims of illegal voting tactics can quickly undermine the credibility of the electoral process. It will be particularly important for the electoral authorities, and the open source community, to assess all claims of violations on voting day quickly and closely, to reduce the scope for deliberate deception.

Scanning Traffic — Vote Rigging

To study the online debate, @DFRLab ran three scans of traffic on a number of platforms from 12:01 a.m. EST, on October 1, to 11:59 p.m. EST on October 30, using the Sysomos online suite of tools. The scans were f0r the terms “vote AND rigging,” “voter AND suppression” and “voter AND fraud.” The platforms scanned were Twitter, Facebook public posts, Tumblr, Instagram public posts, YouTube, news channels, blog sites, and online fora.

The first scan, “vote rigging,” returned relatively few results: 25,065 mentions across all platforms. Over 70 percent were made on Twitter; the most-retweeted posts dealt with questions of vote-rigging in Nigeria, India, and the Brexit referendum, and a tweet from House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi which urged Democratic supporters to vote, while accusing wealthy Americans of “rigging the system” in their favor.

Only two of the ten most-retweeted posts concerned the 2018 midterm elections. Both pointed at the state of Georgia, where Republican gubernatorial candidate Brian Kemp is the current Secretary of State and in charge of voter registration and election processes, a situation which has raised fears of voter suppression (discussed below). Together, the two tweets registered a modest 818 retweets.

Overall, claims of “vote rigging” did not gain significant traction online in October.

“Voter Suppression”

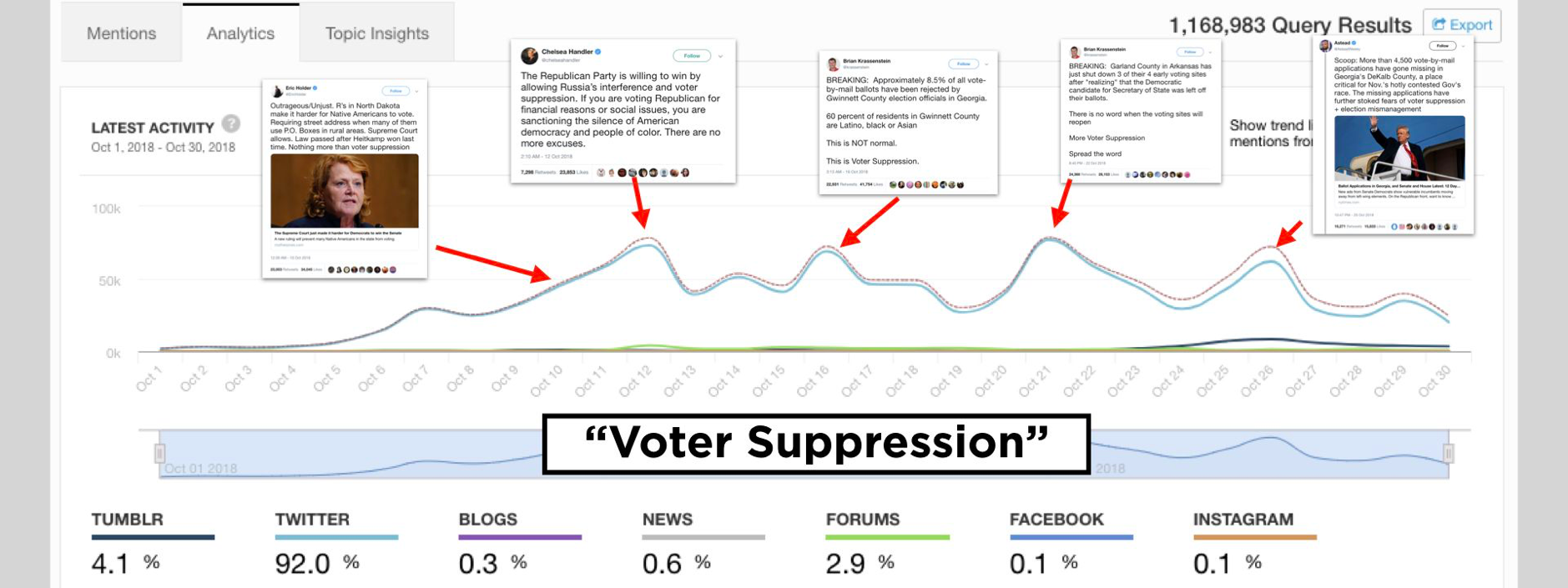

Claims of voter suppression gained far more traction. The Sysomos search for “voter AND suppression” returned over 1.1 million mentions, with the vast majority—92 percent—coming on Twitter.

A timeline of the mentions showed a number of discernible peaks in traffic during the month, notably on October 10, October 12, October 16, October 21, and October 26.

Each peak was largely caused by very high numbers of retweets of a handful of influential posts, each making a specific claim of voter suppression.

Many of those most retweeted posts concerned the situation in Georgia, where Kemp’s role as Secretary of State, and the state’s removal of tens of thousands of names from the voting register, have led to concerns of large-scale voter suppression.

This is a genuine concern, as it would be in the case of any politician, of any party, who is simultaneously running an election, and running for election. A number of independent reports provided details of questionable situations backed by some degree of evidence.

On October 9, for example, the Associated Press reported that the registrations of over 53,000 Georgia voters—predominantly African Americans, a demographic group expected to support Democratic candidate Stacey Abrams—were “sitting on hold” with Kemp’s office. The report was based on the AP’s own reporting and analysis.

Other reports during the month spoke of a disproportionately high rate of rejected postal ballots in Gwinnet County, Georgia, based on an analysis of official county records, and of more than 4,500 mail ballots going missing in DeKalb County, Georgia, based on multiple readouts from a telephone briefing by electoral officials.

Tweets about these reports triggered tens of thousands of retweets. The surge in traffic on October 11, for example, was largely driven by two tweets which referenced voter suppression in Georgia, and scored a combined total of over 17,000 retweets—one quarter of all the Twitter mentions of “voter suppression” that day.

The surge on October 26 was chiefly driven by a tweet from New York Times reporter Astead W. Herndon, breaking the news of the missing ballots. This tweet alone scored over 16,000 retweets, or 26 percent of the mentions that day.

Georgia was not the only subject of such allegations. The spike in traffic on October 10 was driven by a tweet by former Attorney General Eric Holder criticizing the Supreme Court for upholding a North Dakota law, which obliged voters to provide a street address in order to register. Activists and Native American groups in the state complained that this disadvantaged Native American voters, many of whom live on reservations where only a Post Office Box address is given.

Holder’s tweet was retweeted over 23,000 times, accounting for almost half of all Twitter mentions of “voter suppression” that day. This, again, appeared to be a legitimate expression of concern over a genuinely troubling decision. The Supreme Court decision was widely reported; Native American groups later sued the state over the law and other allegations of voter suppression.

Not all claims of voter suppression were based on such substantiated grounds. The spike in traffic on October 22 was largely driven by a tweet by Brian Krassenstein, editor of left-wing, anti-Trump outlet HillReporter.com. This cited a case from Garland County, Arkansas, in which a Democratic candidate was left off early-voting ballots. Krassenstein called this “more voter suppression,” and urged followers to “spread the word.”

The essential facts underpinning his tweet can be verified. The incident was reported contemporaneously by both local and national outlets. However, local radio reported that the omission was rectified and polling stations reopened in an hour; the Associated Press reported that only 222 votes were cast on the incomplete ballot.

Given the glaringly obvious nature of the omission, and the speed with which it was addressed, this appears far more likely to have been a case of human error than deliberate suppression.

Despite this, Krassenstein’s post was retweeted over 24,000 times, accounting for some 40 percent of the mentions of “voter suppression” that day.

Other claims of “voter suppression” also appeared overblown. In July, two hashtags related to the midterms gained a brief vogue. The first was #NoMenMidterms, which was purportedly a Democratic hashtag urging men to stay home and not vote. The second was #DemandVoterID, which was purportedly a Democratic campaign to prevent Russian interference.

Both hashtags were in fact hoaxes which originated on 4chan and were posted to Reddit before surfacing on more mainstream platforms.

According to Sysomos scans, #NoMenMidterms only generated a little over 5,000 mentions, while #DemandVoterID generated 38,000, mostly tweets in July.

Some liberals appeared to take them seriously, with one user on Tumblr posting that the #NoMenMidterms hashtag was being spread by “Twitter bots from Russia or Republicans” tweeting it as “propaganda,” and concluding, “it’s almost like Republicans WANT to spread misinformation and have lower voter turnout in November.”

The post generated significant traffic on Tumblr, considerably more than on Twitter.

In fact, these appear more like pranks, typical of the 4chan subculture, and designed to “trigger” or taunt liberal voters, rather than serious attempts at voter suppression. Their brief existence in July serves as a caution to measure the evidence carefully before alleging actual voter suppression.

Scanning Traffic — Voter Fraud

While the traffic on voter suppression was driven by a number of high-impact users (Holder, Herndon, Berman, and Krassenstein, for example), the conversation around voter fraud was very largely driven by President Trump.

A Sysomos scan of “voter” and “fraud” returned 806,280 mentions through October, with one remarkable spike on October 21.

That spike was driven by a tweet by President Trump, warning potential fraudsters to “cheat at your own peril.”

Trump has a long history of claiming large-scale voter fraud. After the 2016 election, in which he won the electoral college but lost the popular vote by almost three million ballots, he claimed that he “won the popular vote if you deducted the millions of people who voted illegally.” That claim appeared founded on two tweets by a Republican activist who provided no evidence to back his allegations; the tweets have since been deleted, but preserved by fact checkers, who concluded they were false.

Trump later stood up a commission to inquire into voter fraud, but closed it down in January 2018, without providing any evidence to back up his claims. Despite the lack of evidence, in April 2018, Trump claimed that “millions and millions of people” voted many times over in California.

There is simply no evidence to support these claims of massive fraud, conducted by literally millions of illegal voters. The president’s repetition of them undermines the credibility of U.S. democracy in its most sensitive area: the ballot box.

However, his October 21 tweet did not repeat the claim; at most, it can be said to have maintained the narrative of voter fraud, keeping it in the public eye ahead of midterm election in which Democrats are expected to make substantial gains in the House.

The next most influential post on “voter fraud” in October came from political scientist Brian Klaass, and analyzed Republican and Democratic perceptions of voter fraud and voter suppression. Klaass argued that there was no evidence for mass voter fraud, while suppression was “widespread.”

There is ample evidence to back Klaass’ assertion that voter fraud is not widespread. A number of separate studies have concluded that actual voter fraud, such as impersonation or illegal voting, is rare to very rare. The claim that voter suppression is widespread is more questionable, hanging on the definition of “widespread.” As we have seen, there are certainly grounds for concern on this point.

Perhaps strikingly, given Trump’s enormous organic following, his tweet only accounted for some 21 percent of the mentions that day. Hostile replies to it generated more traffic, measured in the retweets of the most influential posts.

A separate Sysomos scan of the terms “voter” and “fraud” in posts between 4:00 a.m. EST October 20 and 4:00 a.m. EST on October 21 showed that, while Trump’s post was by far the most retweeted single comment that day, eight of the ten most-retweeted posts were hostile to him; most cited the situation in Georgia. Together, they generated over 86,000 retweets.

Retweet counts are an imprecise measure of impact, but it is remarkable that no post supporting Trump’s position made it into the top ten.

Of the hostile posts, CNN White House correspondent Jim Acosta quoted Trump’s tweet and advised readers to focus on Russian meddling. Berkeley Professor Robert Reich and former deputy national security advisor Ben Rhodes accused Trump of trying to “intimidate voters.” An anonymous user called @nycsouthpaw made the same claim, and characterized it as “Republicans v. democracy itself.”

The claim that Trump was trying to “intimidate people from trying to participate in elections” is questionable, as it relies on an interpretation of the president’s intentions. It is at least equally possible that he was attempting to show authority, to please his support base with aggressive rhetoric, or to prepare a narrative of fraud in the event of sweeping Republican losses.

Without further evidence, these claims that the president himself was attempting voter suppression in his tweet must be considered unfounded.

Equally unfounded, however, were two pro-Trump claims of voter fraud which generated significant traffic in October. Both were tweeted by Charlie Kirk, the founder of Turning Point USA, a conservative group which aims to “educate students about the importance of fiscal responsibility, free markets, and limited government.”

On October 9, Kirk tweeted that the California Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) had reported that “about 1,500 customers may have been improperly registered to vote most of whom are illegals.”

“Voter fraud is real,” Kirk claimed. His post was retweeted 14,000 times.

The central fact of Kirk’s claim can be verified. The day before his tweet, the Los Angeles Times reported that the DMV had found around 1,500 people who had been wrongly registered to vote under a new registration system which coupled driver and voting registrations. This was on top of a reported 23,000 incorrect voter registrations exposed in September, and a software error which allocated two registration forms each to an estimated 77,000 voters in May.

However, Kirk’s claim that “most” of the registrations went to “illegals” directly contradicted the DMV’s position that illegal residents “are treated uniquely by the department’s computer system and have not been registered to vote in error.” Kirk did not provide evidence to back his claim.

As in the case in Arkansas, the Californian case appears to have been one of gross human (and IT) error. Kirk’s interpretation of “voter fraud” in California appears as exaggerated and partisan as Krassenstein’s interpretation of “voter suppression” in Arkansas.

Finally, on October 18, 2018, Kirk tweeted that Los Angeles county had “admitted” that the number of registered voters was 144 percent of the number of resident voting-age citizens, again making the claim that “voter fraud is real.” He was retweeted over 20,000 times.

The tweet did not give a link, but was a word for word match with a headline on pro-Kremlin conspiracy site ZeroHedge on June 8, 2017.

There are multiple problems with Kirk’s tweet. First, it apparently referenced a story which was over a year old, without providing context. Second, it did not provide any evidence. Third, the “admission” to which it referred was, in fact, an allegation by Republican-leaning activist group Judicial Watch, based on a false interpretation of voter lists. Finally, that false interpretation had been exposed by outlets including the Sacramento Bee, San Diego Union Tribune, and LA Times, at the time.

Kirk’s resurrection of a dated story, stripped of any context or pretense of evidence, appeared a deliberate attempt to revive a false claim.

Conclusions

This traffic, which ran through October, illustrates a key vulnerability of the midterm elections: the perception, on both sides of the partisan gulf, that the outcomes may be manipulated.

Democratic concerns focused on fears of voter suppression. The evidence suggests that some of the claims, in some parts of the country, had enough basis to warrant both concerns and further investigation; however, other claims were not backed by the evidence.

Republican narrative, including those of President Trump, focused on fears of large-scale voter fraud. There was no evidence to support any of those fears; the few detailed claims, such as that of an implausible number of registered voters in California, were demonstrably false.

Strikingly, Democratic claims of voter suppression generated more traffic than Republican comments on voter fraud, and even President Trump’s own post was outweighed by hostile responses.

The greatest danger to U.S. democracy in these traffic flows is the perception, on both sides, that the results cannot be trusted. Such a perception can quickly undermine the legitimacy of electoral results, especially in tight races, such as the Senate contests in Georgia and North Dakota. That, in turn, can only further erode the credibility of U.S. democracy. For the health of the body politic, it will be vital to address any claims of impropriety quickly, and transparently.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.