#ElectionWatch: Misinformation Swirls Around Bolsonaro Attack

After the Brazilian front-runner was stabbed, both left and far-right groups try to shift the news in their favor

#ElectionWatch: Misinformation Swirls Around Bolsonaro Attack

After the Brazilian front-runner was stabbed, both left and far-right groups try to shift the news in their favor

Events leading up to the first round of voting on October 7 in the Brazilian presidential elections took an unexpected turn when front-runner Jair Bolsonaro was stabbed at a campaign stop. Political Facebook pages and groups were quick to amplify false claims about the event. As claims circulated across the political spectrum, fact-checking articles failed to reach impacted audiences.

This incident shows how quickly political groups can exploit events with social media and the challenges fact-checking initiatives face when trying to reach the audiences misinformed by these groups.

The political environment in Brazil is extremely polarized ahead of the October elections. Under these circumstances, two major false claims emerged after the attack. The right alleged that the attacker was from the Workers Party (PT), and the left claimed the assault was staged.

Bolsonaro was stabbed while campaigning in the state of Minas Gerais on Thursday, September 6. The retired army officer is known for his tough-on-crime and pro-gun discourse. He rose to the top of the polls when courts barred former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s candidacy because the PT leader is in jail convicted of corruption.

Bolsonaro’s attacker was immediately arrested and identified as Adelio Bispo de Oliveira. He pleaded guilty and stated he acted following God’s will. On his Facebook page, Oliveira displayed erratic behavior, liking pages across the political spectrum. He posted messages criticizing Bolsonaro, along with others suggesting he believed in conspiracy theories. Oliveira was particularly opposed to the Freemasons secretive society. The police stated he may suffer from mental illness.

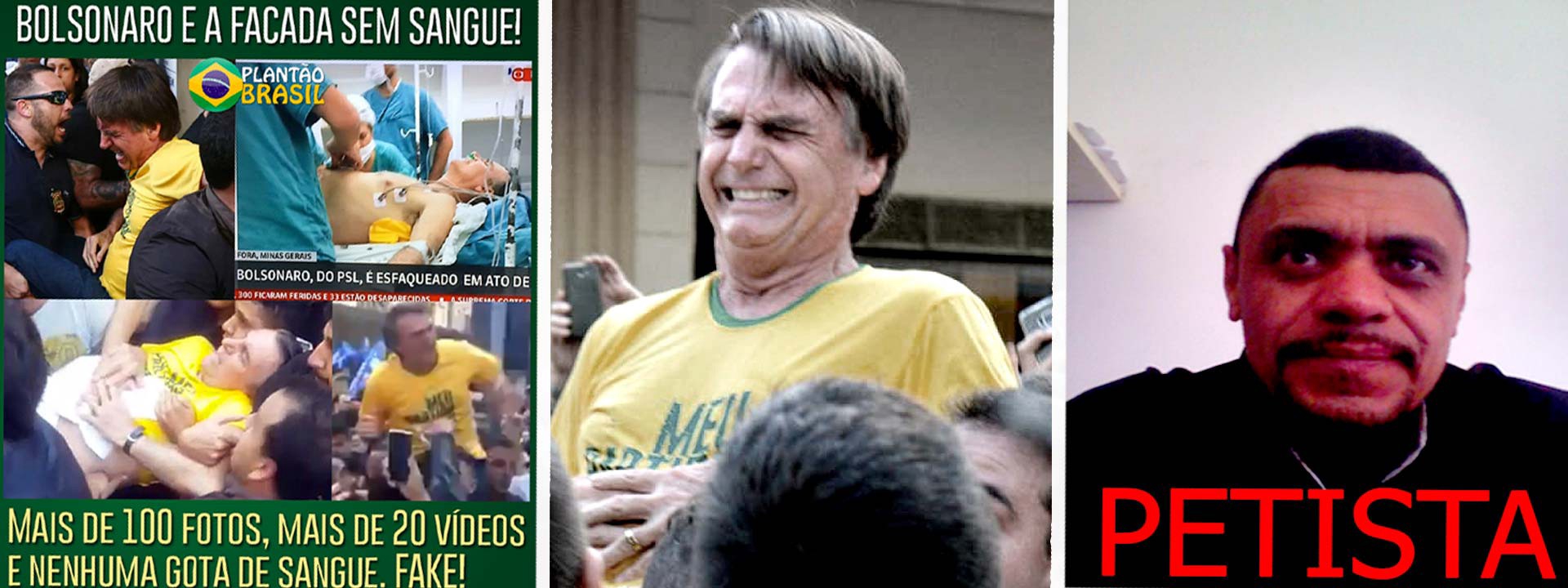

Brazilian social media fell into disarray after the attack. Groups on both the left and right spread false claims after the assault. While left-leaning pages pushed the narrative alleging that the attack was staged to boost Bolsonaro’s popularity, the right claimed it was an organized attempt by the Workers’ Party (PT) to assassinate the popular candidate.

No blood

@DFRLab analyzed the spread of both narratives by performing a search of the words “petista” (a member of the Workers Party) and “sangue” (blood), in social media listening tools. Posts that used these words but did not reference false claims were excluded from the analysis.

Bolsonaro’s injury was not initially perceived as serious, however, doctors detected internal bleeding at the hospital and Bolsonaro underwent surgery. His son, who is also a politician, posted on Twitter that the cut was superficial at first, but later said it was more severe than they had thought. As of September 13, after another emergency surgery, Bolsonaro was recovering well.

On Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp, users pointed out there was no blood in the footage of the attack. Users also noted that a widely circulated video of the operation room showed a doctor without gloves, which gave rise to claims that the operation on Bolsonaro was staged.

For example, the satirical tweet by the account @bchartsnet, published less than two hours after the candidate was stabbed, generated more than 3,600 retweets, using a picture out-of-context (taken earlier that same day in a hospital) to mock Bolsonaro’s perceived healthy appearance after what was “supposedly” a life-threatening event.

Plantão Brasil, the Facebook page of a highly-partisan website, was the main amplifier of the false claim that the attack was staged. Their most influential post, stating that Bolsonaro met with executives from Globo, the biggest media conglomerate in Brazil and later had a “bloodless stab,” garnered 23,457 interactions (likes, comments, and shares).

Three additional posts from Plantão Brasil were among those spreading false claims and receiving a high number of interactions. Most were deleted between Friday and Sunday, but some are still visible on Buzzsumo, as shown below.

The image on the most popular post was heavily circulated on Brazilian social media. It was re-published in several tweets, mostly by accounts that identify themselves as followers of former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

The posts from Bolsonaro’s attack were significantly more popular than usual for Plantão Brasil. The average post from the website plantaobrasil.net garnered an average of 4,000 to 5,000 engagements (the aggregate of reactions, shares, and comments) last year.

Plantão Brasil is the Facebook page of a hyper-partisan left-wing website of the same name. According to a report by researchers Pablo Ortellado and Márcio Moretto Ribeiro, this Facebook page is the main node of a pro-Lula information ecosystem comprising the website and five other pages. The network uses the website, which looks like a news outlet and has a neutral name, to produce hyper-partisan news, sometimes with false information. These articles, which have the appearance of unbiased content, are then spread by the pages forming the system, amplifying their credibility.

Even after Plantão Brasil took down some Facebook content spreading this rumor, several posts on their website still pushed this narrative. One of the posts stated, a “slow-motion video shows that there is no blood coming out Bolsonaro’s shirt,” another lists the “nine reasons of those who do not believe in Bolsonaro’s attack,” and another claims that “Bolsonaro’s fans are commemorating the assault and say that he is already elected in the first round.”

A Master Plan

In right-wing digital pages and groups, some people were spreading the false claim that the attacker was a member of Lula’s PT. One possible reason for this claim was that the attacker had been a member of the left-wing party PSOL, but he left the party in 2014 and had no political affiliation when the attack happened.

The public group “Somos Todos Bolsonaro” (We Are All Bolsonaro) received the highest number of interactions on a post claiming Bolsonaro’s attacker was a member of the Workers Party. The post with a picture of Oliveira and the word “petista” was created by the group’s managers and received 46,605 interactions. Another post from the same group was also on the list of the most successful posts in terms of interactions.

The post claiming Oliveira was a member of PT was 7.6 times more popular than the average posts by the “Somos todos Bolsonaro” group. The post tried to advance a narrative claiming the media were hiding that the attacker was a member of PT. It also included the link to the attacker’s Facebook page.

In all, the analysis showed that the top eight posts claiming the attack had been staged summed up more interactions (94,175) than the ones saying the attacker was from the PT (78,475). The most engaged post was the Somos Todos Bolsonaro post claiming Oliveira was a petista.

Fact checking

The analysis also suggests articles that denied claims were shared only by pages and group that were victims of the false claims and wanted to defend themselves against the rumors. There was no significant cross-ideological spread of the corrections.

In other words, it was unlikely that a user who saw any of these claims later saw the posts correcting it. Most interactions with articles denying false claims came from the media outlets’ Facebook accounts. It was interesting to note that most of the pieces denying the attack was staged were shared by Bolsonaro’s supporters and right-wing pages. Pro-PT and left-wing pages failed to defend themselves — they did not share articles denying the attacker was from PT, as illustrated by the absence of a red dot in the below figure.

The performance of fact-checking articles was assessed by identifying articles that denied false claims. It considered Brazil’s main outlets and fact-checking agencies. Then, using CrowdTangle, it was possible to check which pages and groups posted the debunking article’s URLs on Twitter and Facebook. The graph does not include posts that had less than five percent of the number of interactions of the most successful post (UOL’s post).

Only one page in the sample interacted with false claims as well as fact-checking pieces. Movimento do Povo Brasileiro, a 1.3-million strong right-wing-page, shared the claim that the attacker was a member of the Workers Party and the article explaining why the lack of blood does not support the argument that the attack was staged. They did not share the articles denying the attacker was petista.

It is worth noting that the posts debunking the claim did not fare as well on Facebook as the posts spreading conspiracy theories. This post received only half of the engagement compared to the group’s most popular posts on September 6, the first day it was up.

Posts affirming the facts often underperform on Facebook when compared to those spreading conspiracies. UOL’s Facebook post (archived on September 11) setting the record straight on the lack of blood only garnered about 11,000 interactions, while Plantão Brasil’s piece on Facebook received twice that amount.

Likewise, the Facebook group Somos Todos Bolsonaro’s post (archived on September 11) on the partisan affiliation of the candidate’s attacker (archived on September 11) received over 46,000 engagements, while a post outlining the facts around the attacker’s affiliations published by Boatos — a veteran fact-checking news website — achieved only 1,800 engagements.

Conclusion

This article shows how quickly fringe sectors acted to use an unprecedented situation for political purposes — Brazil hadn’t seen a direct attack on a presidential candidate in more than 50 years. In the aftermath of the attack against Bolsonaro, each sector pushed narratives based on out-of-context and incomplete information.

It is also likely that the spike of interest and traffic in the story was also a factor that incentivized content creators to push these narratives. Groups that shared false claims achieved a much higher engagement rate than usual — this can increase their audience and, therefore, their future relevance in the political debate.

False narratives performed better than those affirming true facts, and the communities that shared each did not overlap. On one hand, this represents a challenge for fact-checkers in reaching audiences en masse. On the other, it is a lesson on how social media listening tools can be used to better identify where false claims are best performing, and to target these communities with pieces debunking the disinformation or misinformation.

#ElectionWatch Latin America is a collaboration between @DFRLab and the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center at the Atlantic Council.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.